Meandering in a Land of Selfless Love

A walk through the exhibition “Le Déracinement. On Diasporic Imaginations”

In spring 2021, Z33 – House for Contemporary Art, Design & Architecture in Hasselt, Belgium hosted the exhibition Le Déracinement: On Diasporic Imaginations. Curated by Silvia Franceschini and including work by artists Mohamed Bourouissa, Kapwani Kiwanga, Raphaël Grisey & Bouba Touré, Mathieu Kleyebe Abonnenc, Fatma Bucak and the Otolith group, the whole visual dispositif of the exhibition was centered around French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s photographic work, produced in Algeria between 1958 and 1961.

Upon visiting, I wondered how an exhibition revolving around the photographic work of a sociologist such as Bourdieu might relate to intrinsically colonial dynamics of uprooting and displacement. But also how a curator operating in an art institution such as Z33 might relate to such a sensitive and thorny topic as diasporic imagination, in the intrinsic contradiction of showing this work within such a—at times violent—context of an institutionalized museum. Nonetheless, I decided to put that set of questions aside for a moment, and surrendered myself to the challenging winding path set out by Silvia Franceschini. My understanding of the process of uprooting and diasporic displacement eventually turned inside out, moved from the liberated land of Algeria and Mali, via the still colonized overseas departments of Martinique and French Guiana, over the hearth of British Empire through the Black Atlantic to end in contemporary war-ridden Syria.

The way Bourdieu spoke about his experience in Algeria, as something similar to a ritual of transcendence—or transformative rite of passage, reminded me of how bell hooks wondered about the conditions of possibility of desire and alterity. As hooks warned us, this desire to understand can act like a critical intervention, challenging and subverting racist domination in the capitalist and loveless world we inhabit, only when it aligns itself with practices of revolutionary liberation struggle. Mindful about diverse forms of collective scholarship that Bourdieu maintained with several important Algerian scholars, artists and poets, and aware of his presence at Abdelmalek Sayad’s hospital bedside before his last breath, I didn’t feel like assessing Bourdieu’s presupposed role in collective organized struggle. Nor was I interested in questioning Bourdieu’s engagement in forms of politicization in Algeria or France, strategies of decolonization, and critiques of capitalism or ongoing resistance to racist domination. [1] As a starting point I took the critical possibility of selfless love and solidarity, beyond any racialized line. Whiteness is after all a construct we all need to escape, in order to abolish it. Taking an anti-colonial, decolonial or anti-racist stance as sociologist or curator remains after all a political choice.

As expected, I was welcomed by a series of well-ordered black and white photographs, and through their selection could get a glimpse of Bourdieu’s germinating method in visual sociology. The series of photos Testimonies of Uprooting introduces the show while it witnesses the different shades of grey through which a sociological gaze slowly gets more acquainted with the reality of colonial violence. Despite lacking some self-reflexivity, Bourdieu captured the life of dispossessed peasants, brutal processes of urbanization and their ensuing marginalization and poverty, but also forms of social transformation through colonization and war, circumventing the existing ossified categories structured by orientalist visual formations proper to some more widespread ethnographic approaches, which were prominent at the time. Nevertheless the series seems to pay justice to the relentless and passionate methodological desire to systematically record, map, categorize and rationalize everything—including the Algerian people and its suffering.

In one of the images I saw a man sitting under a tree next to a child and a dozen villagers posing for the picture. I thought it might be Abdelmalek Sayad, who’s nowadays considered one of the most important scholars within the field of sociology of immigration. When that photograph was taken, he was Pierre Bourdieu’s assistant, with whom he gradually developed a strong academic alliance, producing astounding research focusing on dispossession in Algeria and immigration in France. The gist of Sayad’s writings was carefully collected, ordered and published posthumously by Bourdieu in a book entitled La double absence. Des illusions de l’émigré aux souffrances de l’immigré, later translated as The Suffering of the Immigrant. As Nirmal Puwar remarked, the fact that the postcolonial consistency of Pierre Bourdieu’s work and a large part of its reflection is strongly indebted to his work in colonial Algeria, in particular with Abdelmalek Sayad, is often omitted. Through his experience in Algeria and often along with Sayad, Bourdieu developed much of his political, intellectual and conceptual insights, such as habitus, cultural capital, and social space, among others. Framing himself as an “uprooted intellectual” he felt entitled to “re-appropriate it all in a totally undramatic manner” as he claimed: “Algeria is what allowed me to accept myself. With the same perspective of understanding of the ethnologist with which I regarded Algeria, I could also view myself, the people from my home, my parents, my father’s and my mother’s pronunciation.” He confidently found a way to go beyond the false choice between “populism” and “shame induced by class racism”, although he might have overlooked the power relations traversing what he himself called his “libido sciendi”, meaning the deep and restless passion he felt about wanting to know as much as possible about the Algerians and their country.

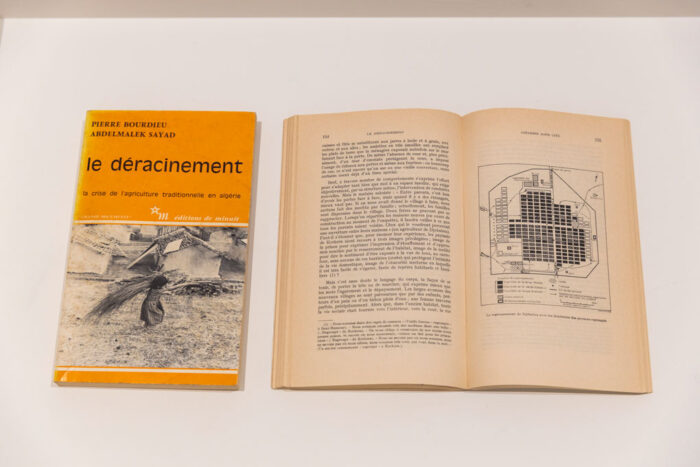

The series of black and white photographs that opens the exhibition seems to serve as a visual introduction to the overall theme of the show, inspired by the eponymous book on The Crisis of Traditional Agriculture in Algeria. In this 1964 book, through their engaged and consistent fieldwork, Bourdieu and Sayad capture precisely how Algerians were driven away from their land by French colonial military forces. Their research serves as record to the violence of one of the most brutal and massive dispossession, displacement and resettlement of rural populations and their rural economy. It maps the creative destruction of the spatial and temporal frameworks of daily life, and shows how this has facilitated processes of spatial compartmentalization and encampment, and of what they called “depaysanization”, meant to transform the countryside into shanty towns and alienate the social fabric of local communities. The book is not simply a document that keeps the memory of the destructive impact of French colonization on all aspects of the Algerian society and culture alive, but also keeps track of how the forced displacement and resettlement of the rural population are part and parcel of the deep logic of any colonial conquest. The violent transformation of people’s habitat is the most assured way to convert and incorporate the envisaged French republican civilization mission. Dispossession and colonial compartmentalization of space are not just powerful measures of social control. The reorganization of the living space and conditions imposed new frameworks of existence, and managed to alter most of the fundamental structures of the cultural systems in place.

The silent sequence of photographs got suddenly interrupted by the arrhythmic murmuring of a yellow-bluish Bird of Paradise flower that manages to catch the attention. The plant was installed there in the corner by Mohamed Bourouissa, as a tribute to Frantz Fanon’s presence in Blida, Bourouissa’s hometown in Algeria. Pretty much like the plant, Fanon arrived in Algeria from the Caribbean after some intermediate steps, to work in the psychiatric hospital settled by the French occupation in the capital. The poetic invitation to listen to the euphonic and vital soundtrack of what is generally seen as a speechless, unanimated and merely decorative artifact invites me to surrender to the worlding experience this Bird of Paradise flowers suggests. This form of blissful surrendering was a daily experience for Bourlem Mohamed, as a main character in Bourouissa’s video The Whispering of Ghosts. Bourlem was one of the inhabitants of the hospital whom Bourouissa encountered while he was retrieving the stories to reconstruct Fanon’s presence in his hometown. Bourlem had benefited from Fanon’s ergotherapeutic structural changes, as he worked on his traumas by transforming the patio of the hospital in a mesmerizing garden. Between 1953 and 1956, Fanon engaged in a rearrangement of the social architecture of the overpopulated and segregated colonial psychiatric hospital, where Christian settlers and indigenous Muslims, men and women were taken care of separately. Slowly becoming more aware of the methodological difficulties to implement a Eurocentric French psychiatric model within this segregated clinical architecture, which was not taking into consideration the actual state of what he called the organic base of Algerian society, Fanon engaged in a series of cultural sensitive modifications taking into account the social morphologies and forms of sociability proper to Algerian ways of knowing and sensing the world.

Bourouissa’s video gives us an impression of the lifeworld of the patient in charge of the hospital’s garden, guiding us through, joyfully recounting the difficulties in overcoming his illness, recalling his life as Fellagha, fighting for the liberation of his people during the anti-colonial War and being tortured by the French colonial police, here explaining how planting and nurturing the hospital garden helped him to reassess these traumatic experiences. The inner voice guiding Bourlem’s gardening endeavors and that of Fanon are not the only one whispering in Bourouissa’s video. French psychiatrist and founder of the Algiers School of psychiatry Antoine Porot also makes his unscripted appearance. The video reminds us that, according to Porot eugenics theories, Magrhebis lacked any conception of time, any critical or conceptual faculty for that matter. As he argued, this resulted from an essential incapacity to symbolize, due to an overdeveloped mimetic faculty. They were considered captives of the image, provoking what Porot called “mimeological disorders”: infectious hysterical conditions, which more often than not developed into full-blown collective hysteria. The scientifically demonstrated primitivism, biological inferiority and inherent pathology of Maghrebi subjects, supposedly manifested itself in a strongly developed an almost compulsive propensity for violence and criminality. Before resigning from the psychiatric hospital in solidarity with general strike of the FLN in 1956 and refusing the implication of the psychiatric institution in the assimilationist and racist colonial politics and its ensuing profound alienation processes, Fanon succeeded in establishing a Moorish café in the hospital, which was organizing regular celebrations of traditional Muslim festivities, and sociable meetings around hlaqia or traditional storytellers.

Bourlem’s spontaneous gardening project captured by Bourouissa was not part of Fanon’s ergo- and socio-therapeutic adjustments, but deeply echoed his methodological reflections on the productive possibilities of working and farming the land as a therapeutic modality, as a spur for re-equilibration. Fanon emphasized the importance of the land as a collective notion structuring social relations in Algerian society. Despite land privatization detribalized and proletarianized the masses, dissolving more collective subjectivities and alienating more traditional social structures, the alienated subjects in the psychiatric hospital were still close to, even making one with the land. In the words of Fanon: “All you need to do is give them a shovel or a pickaxe to get them to work and start digging up earth and hoeing without having to push them to do so in the slightest.” Working the land, gardening and building a different relation to the ground and its living surroundings was already envisioned as a way to overcome the alienating price of damnation, as a way of overcoming the condition of earthlessness.

In four watercolor paintings on paper and the corresponding video Incomplete Herbarium, Bourouissa finishes the staging of his research on the relation between botanic plants and psychotherapy. In the archives of the Catholic Bibliothèque des Glycines in Blida, the artist found an incomplete herbarium book dating from the 1970’s, made by an unknown author. The Herbarium contained a collection of incomplete watercolor paintings illustrating the Algerian Flora, classified by its French and Latin, sometimes also Arabic names. Alluding to the coloniality proper to any form of categorization, Bourouissa nonetheless filmed the process of completion of the herboreal palette he engaged in, omitting what Fred Moten and Stefano Harney would point to as the power of the incompleteness of the Herbarium, fulfilling the original colonial desire to capture nature in never-ending and eventually always contradicting taxonomies.

A more distinct relation to that forceful incompleteness can be found in the series of glazed ceramic seeds presented by Kapwani Kiwanga. For her installation simply entitled Semence, she placed small piles of symmetrically aligned crystalline African rice on a white plateau. The form of the ceramic seeds refer to the Oryza glaberrima, a rice variety domesticated about 2000–3000 years ago in the inland delta of the Upper Niger River, in what is now Mali, before spreading through West Africa. Presented on a white plateau, in a separated room illuminated by the light seeping through the door to one of the many patios of the building, the orderly way these seeds are set up is reminiscent of the way rice is massively being grown on the paddy rice plantations overseas. Together they are tokens of the way enslaved women from West Africa were able to hide these grains in their hair, smuggling seeds for the plot to come, to cultivate the creole garden on the border of the plantation in Suriname and the United States.

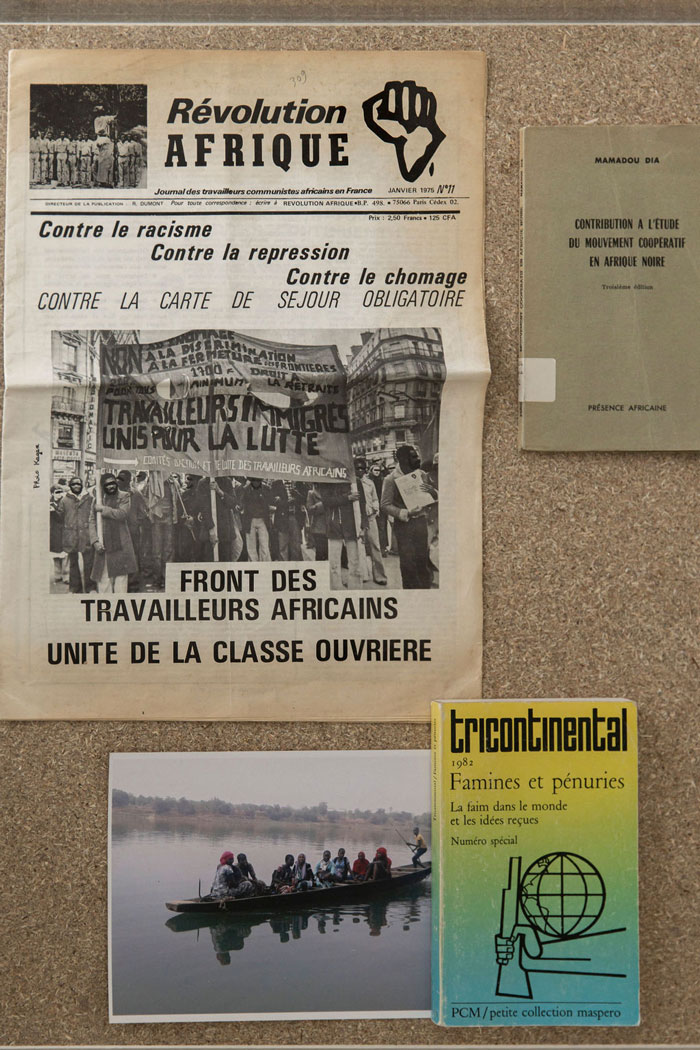

Passing through the archival installation and videos by Raphaël Grisey & Bouba Touré, I was reminded about the productive and generative possibility of return, but also about refusal when confronted with a hostile environment and the impossibility of repair after having sacrificed everything in search of a better life across colonial borders. First shown during Contour Biennale 9 in Mechelen, Belgium, the memory of the Somankidi Coura—a self-organized cooperative along the Senegal River in Mali, founded by a collective of former African “migrant workers” in France in 1977, after the Sahel drought of 1973—is raised like a monument for the enduring story of peasant and migratory struggles. To listen again to the stories of Bouba Touré and Xaraasi Xanne, and to revive traditional cooperative forms and sustainable permaculture as potential gestures of refusal and return, points at the importance of remembering the land and through the land, in its non-marketable ancestral use value. As reminded in his seminal work The Damned of the Earth (i.e. not The Wretched of the World), Fanon famously stated “the most essential value, because the most concrete, is first and foremost the land: the land which will bring them bread and, above all, dignity.”

This quest for freedom and dignity through the re-appropriation and de-commodification of colonized land seems indeed to be one of the curatorial threads of Le Déracinement. In Walking Through the Arawak Horizon, Mathieu Kleyebe Abonnenc gracefully flows with his own personal story, poetically excavating the still very present histories of illegal gold mining, extractivism and ensuing natural catastrophes in the rainforest of French Guiana. For centuries, miners panning for gold have been lured into these forests in the hope of finding their fortune. I slowly become aware of the unfolding environmental disasters, following the traces of Joseph Bernes along the diseased Maroni River, polluted by displaced soil and mercury contamination. Bernes is not only the owner of Abonnenc’s mother’s house in Wacapou, but himself a miner who traveled from the Caribbean island of Saint Lucia to Wacapou in search for gold. Sidetracked by the passing images of the black and white archival images shot in the jungle, in what once was Arawak land, I encounter a number of fictitious objects inhabiting Bernes’s daily life. Inspired by the poetry of Guyanese poet Wilson Harris, different fabricated objects lay dispersed in the room: a seventeenth-century organ juxtaposed in front of a Kuna shaman’s necklace made of Carib bone flutes hanging on the wall, a box with letters, documents and maps, two reddish-brown monochromatic paintings made with cinnabar, a mercury sulfide taken from the mines, and the iconic upside down turtle shell, submerged with residues of mercury.

Likewise in the video Infinity minus Infinity by the Otolith Group, land seems to be a central topic again, albeit in a more tactile or haptic form. Breaking the hegemonic notion of linear time, the more-than-human deities leading us through the introspective futuristic video make the viewer travel through London’s present nighttime. From the 2018 Windrush Scandal, and the possibility to escape enslavement 1831, over the first genocide of modern history in Aby Ala in 1610, to the lived experience of a black woman enduring the racist reverberations of that history in 1933 and its structural civic ramification in the 1948 British Nationality Act. The cinematographic texture of the film and the deities inhabiting the black feminist cosmos this texture allowed to form, points to a shared ability to see the historical present with a third eye. Following Fatimah Tobing Rony, the formative and lucid experience of viewing oneself as an object marked as an Other, wrapped into devastating objecthood, helps to become aware of the very processes which create these forms of alienation in the first place. When one sees that one is not fully recognized as Self by the wider society and also refuses to be identified as Other, boundaries are blurred and the question of becoming is left in an uncomfortable suspension. In this ways the third eye that rises out of the deep and black meditation facilitates new yet undefined ways of looking, not only at the history of slavery, colonization and blackness, but also at its deep entanglement with its relation with the earth and the manifold earth-beings it inhabits.

Starting from the “matter” within Black Lives Matter, the Otolith Group invites us to a sensible extra-temporal space to think about the kind of matter or histories of matter that violently enforced and still enforces embodiments over intimate servitude and forced labor globally. Diving into the geo-physics and geologies of this very matter, the video enacts a generative refusal of the enslaved black body as a pars pro toto for the infrastructural and extractivist forces still determining the enslaved world and ongoing planetary geological disasters. The storm of wounds and scars of black suffering that resonates with the lightning phrase “I can’t breathe” later becomes a premonitory sensibility for the lack of oxygen due to global warming. Starting from the end of the world, somewhere where the before and afterlife of slavery meet, this poignant black meditation reminds us that the apocalypse is not something that might happen in the near future, but is ongoing since 1492, since the conquest of Abya Yala and its ensuing Orbis Spike. The video ends with the simple statement that, whereas ice core records can meticulously reveal that today CO2 levels far exceeds any present on Earth within the last 8000000 years, answering the unquestioned question “why don’t black lives matter?” in simple binary terms remains an impossibility. As blackness cannot be a counterpoint to life, in the light and power of the sun, they both remain undefined, undeterminable, incommensurable and formless in their mutually entwined infinity. Bringing the very question of being and becoming in uncomfortable suspension, it paradoxically enables through its tactile and haptic embodied suggestions, new ways of getting back in touch with our earthly surroundings, new ways of worlding from a grounded surround in its most uncanny vital sense.

My meandering through Z33 ends with a soothing short, but hopeful salute of a dozen of Damascus roses. Endangered with extinction in war ridden Syria, Fatma Bucak smuggled young cuttings of the rose from fields outside Damascus to Belgium. After a voyage of more than three thousand kilometers, burning different colonial and still conflictual borders underway, this flower bears witness to the steadfast perseverance needed today by so many of us. At the same time the pacifist gesture of re-growing a soothing rose reminds me about the inevitability of re-emergence and the irrepressible possibility of selfless love.

Walking out of the building, I am left with a feeling that the exhibition seems to be as uprooted to the diasporic imagination of its immediate surroundings, as its title suggests. I didn’t have to look far to reach this imagination. I walked to the city library of Hasselt where the visual poem Prends soin de toi... by poet Lisette Ma Neza and filmmaker Maja-Ajmia Yde Zellama was on show. By bypassing this flourishing diasporic imagination nearby, the fine selection of international artists and their imaginaries in Z33 seemed to be likewise deracinated from their immediate surroundings, to lack solidarity with it. At times it felt like it only resonated in the self-sufficient echo-chamber of the comfortable globalized white cube. As repeatedly stated by Olivier Marboeuf, the white cube could be understood as a plantation in itself, generating the impression of an all-encompassing totality, all the while suffocating the conditions of possibility generated by the selected artists to work from and in relation with an imaginable outside to criticize the Plantationocene. At the same time Marboeuf’s critique defies us with what almost feel like an impasse, which might actually also be a way out, as it confronts us with the challenging possibility to blow life in the still-life of what is left of the institutionalized visual arts and its inanimate subject matters. By doing so, it also sharpens the distinction made in the exhibition and its curatorial sensitivity, having assembled different propositions that together make the manifold relations between the real, the imaginary, the symbolic and the ecological, as well as decolonial interrogations inescapable. As if the Eurocentric critiques of the Anthropocene or the Chthulucene are nothing to catch up with. Like many other imaginaries, it was already there, long time in the making, long time in the waiting, as it endured the endlessly repeated but failed attempts of obliteration.