Algeria: Flowering of the Uprooted

The garden as a private, political and historical space in colonial and postcolonial times

This text is part of ORTO, a publication by Roma Calling 2019/2020 Fellows in collaboration with Saul Marcadent, with contributions by Armando Bramanti, Dominique Laleg, Anaïs Wenger, Charlotte Matter, Pauline Julier, Real Madrid, Nastasia Meyrat, Urs August Steiner, Francesco Dendena, Kiri Santer, Johanna Bruckner, Romeo Dell’Era. ORTO is the result of a collaborative zeal between art and science and highlights the common desire to cross barriers and overcome distances, albeit symbolically. Conceived in singular circumstances—swift e-mail exchanges and long video calls— the book contains heterogeneous materials able to reproduce the fellows’ experience.

My grandmother had a big garden on Algeria’s Mediterranean coast. Each morning at dawn she got up, and after saying her prayers, went out to water the flowers, vegetables, and trees. I remember hearing the sound of the garden hose when waking up in the summers. As I went out on the balcony overlooking the garden, she would smile at me, the hose in her hand, from where the cold water splashed and trickled onto the dry earth.

Even though the garden was surrounded by high walls, it did not feel enclosed or isolated. Stepping into the garden from the outside world, with its dusty and noisy streets characteristic of a North African town, the garden appeared as a calm and pleasant place where one had the space to breath.

My grandmother, who in her older age rarely left the house, loved her garden very much, and so did we. As kids, my cousins and I spent days playing in that garden, climbing its trees, digging holes, and catching butterflies. Most of the time we would run around barefoot, and the feeling of the dry earth on my skin or the sensation of stepping on a squashed fig which had fallen from one of the trees is among my most vivid childhood memories. Sensory memories of the rough apricot tree bark grazing my skin had I not been careful, or the smooth, greyish fig tree bark ideal for climbing, although more slippery.

These deeply embodied memories are also related to the North African climate, which gives the garden a special sense of importance. Albert Camus has described Algeria’s pitiless heat and harsh, sometimes brutal sunlight. His writing is grounded in this bodily experience far more than in abstract theories. While European romanticism and its aesthetics are based on inner emotions, the native Algerian Camus developed his tragedy of the human being from the bodily sensations responding to the Algerian sun, earth, and sea.

The garden as place of peace and rest occupies an important role in Middle Eastern culture as a whole, with relevant examples found everywhere from Kabul to Marrakesh. Anyone who has ever visited the Moorish garden, Carmen de la Victoria, in Granada or the Bāgh-e Fin Garden near the Iranian Town of Kashan knows the feeling of stepping into these places on a hot day. They provide a combination of cooling physical sensation, scents of flowers, calmness, and of course, aesthetic pleasure.

The latter reminds us that the garden is not nature as such but organized by principles that add structure and artificial shape to it. It is, in particular, the combination of the plants’ natural vitality with this artificial order that creates the aesthetic characteristics of the garden, as well as the involvement of the body and the senses. Could Immanuel Kant have separated sensory judgements from aesthetic judgements had he never left his home town Königsberg to visit the lemon gardens of the Alhambra or the rose gardens of Shiraz?

When Algeria was conquered by the French in 1830, they knew about its fertile lands and favorable climate. The French historian Clausolles writes about the “perfectly well-behaved gardens of the Berber people” in L’Algérie pittoresque, ou, Histoire de la régence d’Alger, published in 1843. They contain, he further describes, “a large number of fruit trees, such as oranges, pears, apples, apricots, peaches, etc. The vine provides grapes in abundance. The olive tree is the tree they cultivate best; it alone occupies almost all their care; they extract magnificent olives from it, from which they make oil, use them to make soap, spin wool, and preserve the olives themselves.”

Among the first projects the French established in their new colony was the Jardin d’Essai in Algiers, which was a botanical garden and tree nursery. The enormous park measures 150 acres and continues to be open to the public today. It is home to huge water basins and palm forests, and due to its atmosphere, served as a setting for the film Tarzan the Apeman in 1932.

The famous Jardin d’ Essai was not just a vanity project for the colonizers, it also served the function of cultivating imported plants from all over the world. As its name suggests, the purpose was to test their suitability within this newly conquered territory. Such a practice demonstrates one of the central strategies adopted by the colonizers: the conquering and controlling of a colonized place followed by the removing and transfer of local “goods” to another colonized place, with the goal of expansion and profit. Italian born botanist Gaetano Durando was able to cultivate Asian tobacco in the Jardin d’Essai, which he sold on favorable terms to French settlers in Algeria.

Such logic was cruelly often used for people as well as plants. One example is the forcible resettling of more than two thousand local Algerians in the late 19th century to the newly colonized south pacific islands of French Caledonia. The systematic and violent displacement of plants and people is at core of this colonial logic, which became particularly brutal again during Algeria’s War of Independence, which lasted from 1954-1962. During that period, more than 3.5 million Algerians, about a third of the whole indigenous population, were resettled by the French army. Their wonderful fruit and olive trees were taken from them and the majority of the people had to stay in newly built camps, which were often a rigid grid of modern building whose residents were controlled by the French army.

The destructive impact on Algeria’s population by these resettlements has been critically examined by the sociologists Pierre Bourdieu and Abdelmalek Sayad, who conducted intensive field research in the area during and after the War of Independence. Bourdieu described the traumatizing impact on the Algerian people—especially on the rural population, whose traditional identity has been strongly anchored in their lost farmland—as “uprooting”.

There is a crucial difference between colonialism and settler colonialism: while the first is a form of exploitation and submission of indigenous people and their culture, the latter is their destruction and replacement. The overtaking of the fertile soil at the core of the settler colony was examined by the Algerian by choice, Frantz Fanon, when he wrote “for a colonized people the most essential value, because the most concrete, is first and foremost the land: the land which will bring them bread and, above all, dignity.” No political participation, no human right and no cohabitation can replace the elementary need of the uprooted for their land. “The immense majority of natives”, argues Fanon in 1959, “want the settler’s farm.”

After Algeria became independent in 1962, my grandparents bought their first big house with a garden from a French settler, supposedly at a good price. The scenes must have been dramatic and disturbing, when one million French settlers, many of them born and raised in North Africa, had to leave their homes to migrate to the French motherland across the Mediterranean Sea. For many France was a foreign country, and as immigrants they were not always welcomed.

Just as one man’s loss is another man’s gain, one nation’s reconquest can cause another’s trauma. During this time, my family had fate in their favor. They moved into a marvelous and spacious place made of whitewashed walls with painted blue wooden shutters. A winter garden connected the vine-shaded courtyard with the flowering garden where my grandmother would grow fragrant jasmine bushes and sweet peaches.

A revolution is a singular moment of disruption within a seemingly established order of history. It comes with a reverberation of victory, in which the revolutionary can enjoy the dramatic change of his role. From being a brave freedom fighter, constantly in fear of his life, his situation suddenly becomes powerful and comfortable. But despite big parades, monuments and heroic reports, the reverberation of victory is not endless and the revolution becomes historical itself.

At some point the revolutionary has to face the responsibilities that come with his new role. He is now leading a free country, with an official government, an economy, diplomatic relations, an education system, etc. The fighter’s courage is undoubtedly great, but his skills in running a guerilla war will eventually turn out to be different from the capacities needed to run a country. “Il faut cultiver notre jardin” are the well-chosen words by Voltaire to end his Candide ou l’optimisme.

After a while, reality caught up with postcolonial Algeria and its glory turned to disillusion. Some three decades after its independence, a combination of bad governance, corruption, social crises, and religious fanaticism plunged the country into civil war. It began with the brutal suppression of social unrest in the late 1980s and was followed by more than ten years of bloody fighting between radical Islamists and the military-run government.

This period, to which Algerians refer to as the “décennie noire”, fundamentally changed the country and its people. Public spaces turned into dangerous warzones, neighbors into potential enemies, and the famous Algerian joie de vivre gave way to fear and distrust. An atmosphere of anxiety overshadowed life, and people were driven largely by survival instincts, which, above all, meant becoming as invisible as possible. Close the windows and shutters! Turn the lights off! Switch off the radio! Dress discreetly! The threat to life meant that everyone practiced this mimicry, which suppressed personal freedom and the expression of individuality, towards a total uniformity of the masses. Yet even then, staying alive was not a guarantee. At times intentionally, like the writer and poet Tahar Djaout in 1993, or by accident, like the hundreds of inhabitants of the village Rais who died in a horrific massacre in 1997, the total number of victims rose from week to week to reach a total sum of up to one hundred and fifty thousand by the end of the 1990s.

My closest family was lucky. They got away. What remains with them, however, are lasting memories of fear. I recall clearly hearing gun shots outside the house while lying flat on the floor with my cousins to hide from possible ricochets. I remember the frightening sound of soldiers’ boots through the nightly silence, the army checkpoints along the coastal roads, and the closed beaches, which were turned into military zones.

My grandmother’s garden become a refuge, a retreat into privacy that allowed the family to escape cruel reality, at least temporarily. Camus once wrote: “the sun told me that history is not everything.” Indeed, the flowering trees and the fertile soil seemed indifferent to the frightening ideologies and waves of violence taking over the outside world.

Nevertheless, the garden’s topology had changed. The trees could not hide the barbed wire on the wall tops, and the night-time curfew prevented us from enjoying mild summer nights under the starry sky. The enclosed garden has become a symbol for the topology of Algerian society since the 1990s. The sharp separation between the public and the private, between society and family, between danger and safety. “Get inside” was the sentence most heard by children of the time.

The impact of this separating topology and social mimicry continues to dominate today’s Algeria. Years of self-isolation and conformation have had a deep impact on social life, and therefore, on the political culture of the people. Public life is of crucial importance for a democracy, which requires a space for discourse and a place for its civil society. Only a common space allows individual inhabitants to come into contact with one another, to face each other’s differences and open conversations about their needs, ideas, and dreams. The retreat into the private, into the shelter of the family, can cause an atomization of the collective. It therefore limits this exchange, one which is essential to any democratic society, perhaps to any society worthy of the name.

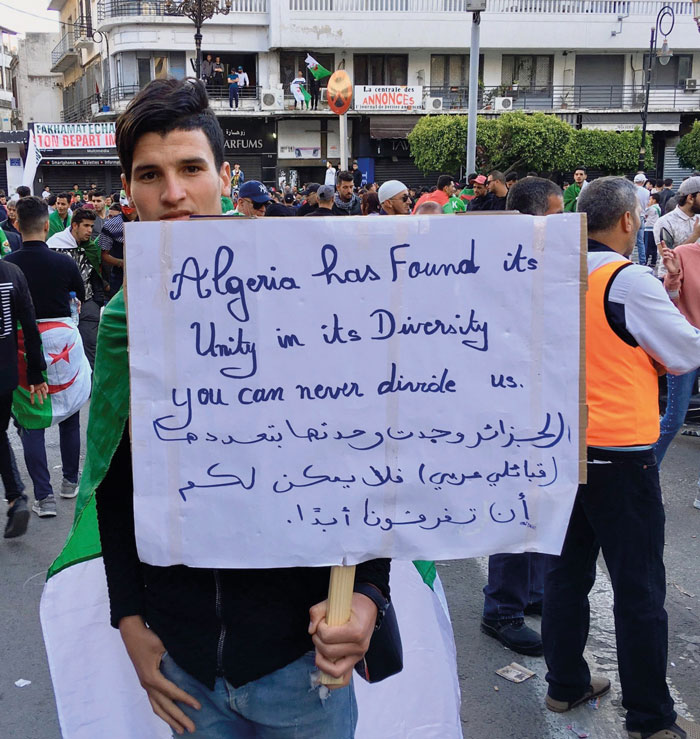

Only in recent years have Algerians begun to reclaim public space. The massive popular uprisings since February 2019 have marked a revolutionary change in the country’s social and political life. Suddenly, millions of people came together to claim their rights for political participation, for the separation of powers, and against the devastating corruption. People of all age, classes, and ethnicities found themselves standing side by side, protesting for a better and more just future. Conservatives and liberals, Islamists and Secularists, Salafists and Feminists among them, all walked down the streets together, week after week, chanting the same words: “Down with the system! Away with the murdering power! We demand that you all vacate!” More than half a century after the glorious independence of Algeria, everybody was aware that the liberators had become oppressors and that the people had been betrayed.

In spite of their differences, the solidarity among the protesters was as overwhelming as their passion and braveness. I remember recently a young man standing in the shouting crowd, on a square in the capital of Algiers during a sunny Friday afternoon. He held a poster in his hands that expressed arguably the most important sentiment about these uprisings: “Algeria has found its Unity in its Diversity.”

Even though the protesters’ demands continue to be widely ignored by the ruling army and politicians, the masses have, nevertheless, reestablished the conversation among themselves and are therefore becoming a people again. Thanks to the Arab Spring, the uprooted have started blooming again. Even if the future seems uncertain, and there are reasons for a pessimistic outlook, an irreversible step has been taken.

My grandmother passed away in 2017. My uncle has continued to care for her garden since then.