Derek Jarman’s Garden

Anne-Laure Franchette and Elise Lammer on the queering of Nature

Conceived jointly by Basel-based curator Elise Lammer and La Becque | Artists Residency, on the shores of Lake Geneva, in Switzerland, Modern Nature: an homage to Derek Jarman, is a 3-year project that comprises the development of a garden and artistic program inspired by the life and work of British filmmaker, artist, activist Derek Jarman (31 January 1942–19 February 1994). The garden located on the lakeside grounds of La Becque is a tribute to the garden that Jarman developed at his Prospect Cottage in Dungeness, on the southern coast of Kent between 1986 and 1994. Far from a perfect copy, La Becque’s Jarman-inspired garden is in fact a reinterpretation of the principles that guided Jarman throughout his gardening. Namely, working with local and native species, using found elements to create a scenography, thinking of biodynamic arrangements for the best efficiency, and avoiding walls or fences. In late summer 2019, a first selection of living artists were put in dialogue with what was still a sparse garden and a rather minimal research archive. Ranging from people who had worked closely together with Derek Jarman to younger artists whose practice strongly resonated with themes dear to him, the cohort’s connections to Jarman were somewhat intuitive and endorsed the capacity of his legacy to transcend generations and geographies. The first series of works newly conceived or adapted “for” this Swiss version of Prospect Cottage emerged under the overarching theme of “camp”. For the second chapter, a selection of artists and guests were invited to respond to the notion of “queering landscape”, unveiling newly-produced sculptures displayed in the garden, as well as readings, film screenings, and various artistic and music performances.

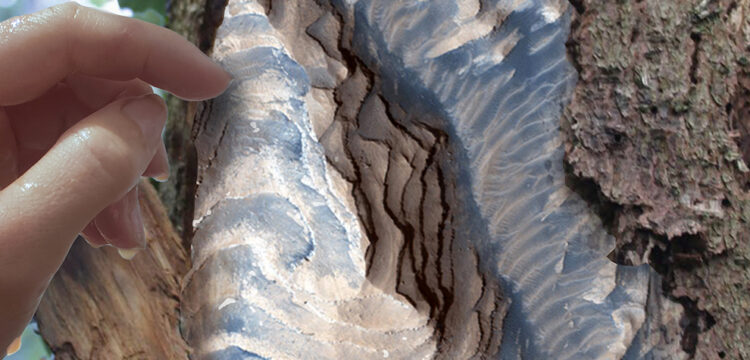

Elise Lammer: The British avant-garde artist, film-maker, author and activist Derek Jarman (UK, 1942-1994) collected fragments of anti-tank fencing and other WW2 remnants to build little climbing frames or shelter for the plants he was cultivating in the garden surrounding his cottage in Dungeness. Located on the south coast of Kent, this part of England is also called “the desert of England” for the seemingly inhospitable landscape it offers. Nevertheless, it hosts an incredibly rich and diverse biosphere, and its wind-beaten shores are the home of a coastal bird sanctuary. Originally a fisherman’s cottage, the home Jarman purchased shortly after being diagnosed as HIV positive, was located directly on the shingle, and overlooked by a partially decommissioned power plant.

Industrial and political leftovers were colonized by a vigorous, nuclear-infused nature, in what can be understood, in light of Jarman’s interest in historical narratives, as an example of pre apocalyptic modernity. Jarman’s filmic work was famously questioning and often disrupting conventional readings of history, and Prospect Cottage arguably provided a fertile background to the last works he created before passing away in 1994. Modernity, often presented as a period disconnected from the past, and alien to the concepts of nature and life, was in fact materialized within Jarman’s garden, in what I interpret as an ultimate act of reconciliation. In light of this anti-nostalgic perspective, Prospect Cottage was accommodating all earthly forces—natural and industrial—without hierarchy, breaking up with the Christian principle of moral and aesthetics, which Jarman, a notable atheist, was rejecting.

I always felt uncomfortable with the nostalgia attached to Nature, as if an untouched Garden of Eden; some sort of perfect pre-cultural or pre-modern environment would ever have existed. Such a concept is very persistent and even dangerous when it comes to thinking about the current environmental crisis, as it dismisses the agency of humans, which is the main driver of destruction, but also positive change.

Jarman’s achievements in his garden were at times hindered by the progress of the disease and without a doubt influenced by the ebb and flow of his treatment. Masterfully documented in Modern Nature (1992), the autobiography and memoir he wrote at the time, such interaction of forces resulted in what I understand as a form of symbiosis between Jarman and his garden. This is where the concept of “queering nature” could be useful. Arguably, Jarman was transferring a life that was approaching its end into the soil. Queering equals here to simultaneously changing one’s environment and being changed by it, in a synergy of forces that is ultimately de-hierarchized and symbiotic.

Anne-Laure Franchette: There has been a number of interesting works and studies lately, stemming from the interesection of queer, decolonial and ecological studies. The idea of queering nature can offer tools to explore questions of social deconstruction and territorial decompartmentalization, but also self consciousness, fluidity and mutability. How can we attempt a queer reading of nature, using the case study of Derek Jarman’s garden as a departure point?

The romanticism of myths of return, thinking about where we came from, connects us with our current idea of what nature is, which is largely, as you mentioned, a space of anti-modernity. Jarman didn’t settle within a bucolic and preserved countryside but within an interface, a land where different types of nature meet, a land bearing the marks and influences of urbanism and industrial processes. A rather brutal or brutalist landscape. Unlike many gardens, the grounds of Jarman’s cottage were not designed as a demonstration of power. Rather as a celebration of growth and existence, while also standing as a memorial to silence and disappearance.

Looking for permanence and a sense of place seems to be a common human struggle and quest. How do we place ourselves, physically, historically, politically, conceptually, in the spaces we inhabit or/and drift through? Through memory, but also through imagination? Our lives, those of other species as well as the land itself, are caught up in the moral webs and preoccupations we spin. And the laws of civilization have not been thought in a compatible way with its original environment. New ecosystems have emerged, incorporating both living and nonliving things and standing, alternatively, somewhere between ruins and utopia.

Thinking about the symbiosis Jarman developed with the land and debris around him strongly reminds me of Ana Mendieta. In her earth body works, she was becoming one with the natural elements around her, carrying a dialogue between the landscape and the body. While Jarman planted both his garden and himself in Dungeness, creating a constant dialogue and balance with his surroundings, Mendieta’s work rather talked about being unrooted. But what both established in their work was bodily bounds with landscapes, in connection with a universal energy, which runs through everything. What do we look for through symbiosis? Balance? Healing? Closure?

EL: I like the concept of energies fluidly navigating species and objects. And it’s hard to avoid reading Prospect Cottage as the ultimate repository of Jarman’s life and work. In 1986, shortly after being diagnosed HIV positive, Derek Jarman was touring the south coast of Kent while scouting for a film location. Following, he bought a little plot of land together with a wooden fisherman’s shack that he converted in the place now known as Prospect Cottage. He spent most of his time there until passing away from AIDS-related illness in 1994. During this 8-year window, Jarman had consciously decided to stir away from the capital, and except from the regular trips to the hospital he had to do to receive treatment, he was in Dungeness most of the time. He created a garden in a very challenging environment, almost forcing nature to thrive, bloom and grow against the constant wind and salt mist. When he wasn’t gardening, he wrote his memoirs, as if he knew Prospect Cottage would be his last earthly home. The concept of “queering nature” described above can be understood as forcing life to emerge out of nothing, or as a transfer of the liveliness that his body was losing into a garden?

ALF: Jarman’s body is strongly intertwined with his garden. Many of his bodily actions relate to the garden, where a constant dialogue between the order and disorder of things, between ends and beginnings, takes place. This idea of ongoing cycles and energy transferring between various beings and bodies, one medicalized and becoming less able, echoes strongly for me with Sharona Franklin’s slowly dissolving bio-shrines, which stand as monuments to her treatments. Questioning ecological systems and ethics of biopharmacology, these gelatin sculptures parallel the transient nature of both hers and Jarman’s body. Living is producing, constantly adding to the cycle. So how does the garden of Prospect Cottage embody Derek Jarman? There, all beings and objects can be seen as in transition and undergoing reinvention. Stones, drifted wood or metal parts create a nostalgic landscape. One with history and a new-told story. Repurposing and recycling are an integral part of artistic practices. Reusing allows us to look at and question what has been produced, in which conditions and for whom? In the act of repurposing, there is an acknowledgment of the existence and past use of objects, paired with an erasure and reinvention of their identity and sometimes purpose. The initial frame of creation can be transcended, in an act of political poetry. If we understand a methodology of queer reading as a movement towards fluidity, fighting normalization and challenging identity politics, one may wonder for example, if a readymade could not be described as a queer artifact by essence?

EL: Well, I suppose that with Jarman’s use and rearranging of found objects, I’m torn between the notion of a Duchampian readymade and that of straightforward recycling. Both concepts are queering or steering away from a function that was designed by hegemonic systems, and often ruled by market economy principles. Additionally, we can connect the two concepts as they both rely on a constructed set of references, who need to be questioned in order to spark a cycle of either conceptual or tangible transformation. The bottle rack opens a new network of semantic relations, while the vegetable scraps breaking down into nutrients open a new network of lively relations. The notion of productive transition is very useful here, as it helps understand how the objects Jarman found around the cottage were at once artifacts and supports for the plants.

ALF: In the idea of symbiosis and productive transition, the objects repurposed by Jarman seem like bones, traces or fossils of different material bodies which, unlike flesh and plants, cannot return to the humus and lie around on the surface. They become containers for plants but also receptacles of fears, wishes and nostalgia. Some sort of totems. Looking at how we can transform our relationship to the natural, using queer reading and a more fluid ontology to other aspects of life, can help us question what lies beyond common ideas of naturalism. For Chaia Heller, “love of nature is a process of becoming aware of and unlearning ideologies of racism, sexism, heterosexism, and ableism so that we may cease to reduce our idea of nature to a dark, heterosexual, ‘beautiful’ mother” (For the love of nature: Ecology and the cult of the romantic. 1993). But to answer with another quote, from Caitlin Marie Doak, we may wonder why “ideas, spaces and practices designated as ‘nature’ are often so vigorously defended against queers in a society in which that very nature is increasingly degraded and exploited?” (Queering Nature, 2016).

EL: We could add to the list the concept of “Mother Nature”. Stemming from conservative Christian principles of moral, the term condemns same-sex queerness as deviant from the patriarchal and heterosexual norm supposedly promoted in the Bible. To go back to Derek Jarman, I have the feeling that he nourished both a respectful fascination for Christianity, while entertaining a profound disgust for the church. As Dominic James rightly wrote in Visions of Queer Martyrdom from John Henry Newman to Derek Jarman (2015), Christianity and homosexuality were strongly intertwined in the Victorian 20th century England. He argues that “the subject position of Victorian ecclesiastical queerness was one rooted in eroticized shame and suffering,” further suggesting that the work and life of Jarman provided a clear example of queer martyrdom, as subjects of both gay oppression and liberation. James’s interpretation might sound a little essentialist, so I would like to broaden the debate to include the full spectrum of queerness. I think that Jarman’s Dungeness project was exemplary in establishing a new order in morals, norms and beauty by means of a garden, which in fact connected a space designated for “nature” to the queer. Going back to our common attempt to define and understand what queering nature might be, “queer” as a verb has the capacity to dismantle essentialist views about nature, but also gender and sexuality.

ALF: Talking about guilt and suffering, in direct connection with minds and bodies, finds today a counter argument in the politics of healing and happiness pronounced by Pleasure Activism. Rooted in black feminism, the term was coined by Adrienne Maree Brown and shows how emotional and erotic desires can be activated against oppression. Following these question of authenticity and what the “natural” may be, in relation to non binary intersections of plant life and sex life, also makes me think about the work of Zheng Bo. In his videos, a very physical and pleasurable kinship with nature is showcased. A different cosmo-vision. One that highlights questions of engagement, oppression, exploitation and consent of nature. In these footstep and as Teresa Castro puts it so well, “ultimately, we need to rebel against ourselves: maybe the mediated, sentient, intelligent plant can help us to queer ourselves-as-humans (…) Because queer has never been only human. Because queer can be a way to reimagine what it means to be “human” in the age of man-made ecological catastrophe, as we estrange ourselves from dualistic identities and an oppressive mode of being human. Because queer is a means to push forward the boundaries of our thinking about ourselves in relation to all the meaningful others who share the world with us. Because queer is about identity and inclusion.” (Queer Botanics, 2019)

EL: In regards to the production of space, Derek Jarman’s garden can make us wonder how horizontal relations between human and non-human bodies can be achieved. Exploitative capitalism, as well as heterosexism are among the most oppressive power structures through which human interactions with nature are devised. By means of his films, activism and eventually his garden, Derek Jarman has achieved interesting aesthetic, political and ecological landmarks to challenge some of these structures. The fact that his work went mainstream at some point and is currently enjoying a revival of interest, stands as proof that not all of us are happy with the current regime of ideas, fueled by consumerist and oppressive policies; I’d like to imagine that Jarman, as a queer figure, might have an engaging set of experiences to learn from so to develop a more critical, ecological and political agenda.

ALF: Current moral imperatives are slowly leading us toward this direction, yet it seems indeed hard to implement it in light of the current economic system. Will man ever be able to consider and treat equally what he has seen as subjects, assets and resources since centuries? For we are skeptics who refuse to believe without direct personal experience, just as Apostle Thomas refused to believe Jesus had resurrected, until he could see and feel his wounds. Urban citizens visit the countryside or nature parks to “resource” and reconnect with the idea of an unspoiled natural world, uncorrupted by civilization and therefore fundamentally good. In this process of glamorization and stereotyping, we exoticize the natural world, which we think as external to us. For there is always this curiosity in the other, everything we think of as the outside. Can we look at nature as an otherness within ourselves? I like what Georges Perec calls the “endotic”—a conceptual tool, which approaches everyday life and one’s own immediate surroundings. Emulating a fascination that comes from the very fact of exploring, it is applied to seemingly mundane and overlooked assumptions.

Beyond thinking of queer as an ideality, to quote José Esteban Muñoz, how can we practically deconstruct the logics and frameworks of our everyday reality? How can we rethink the dynamics of power that persist within our own subjectivity? How can we reconsider the overlooked and undervalued, within and around us? Those are questions I ask myself, while attempting to explore the layers of identity and hierarchies of dignity, contained within the specific tools and materials I use. The legacy of Derek Jarman, especially his garden of Prospect Cottage, provides us with a variety of entry points through which we can think through these questions of deconstruction, relations and symbiosis. Challenging and reconciling binaries such as industriality and pristine environment, normativity and fluidity, or external and inner nature.