Werk Werk Werk

Letizia Calori “Hard Work” at Marktstudio, Bologna

Conceived by the artist Giuseppe De Mattia and developed under the artistic direction of Enrico Camprini and Chiara Spaggiari, in collaboration with Angelica Bertoli and Alessia Sebastiani, Marktstudio has presented Hard Work, an exhibition project by Letizia Calori, a reflection on the materiality of the everyday object in physical and social space and on the contradictions generated by its remodulation and exposure.

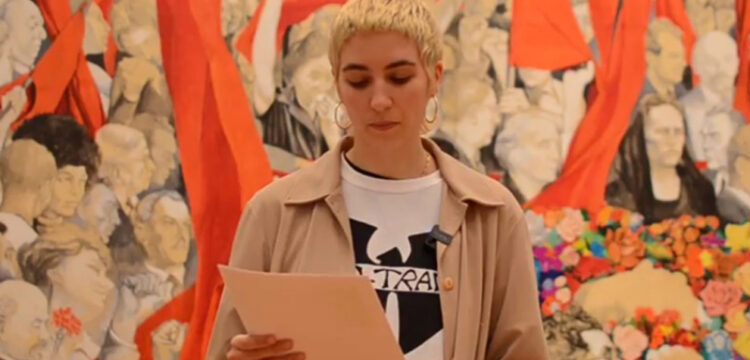

Letizia Calori’s work is a continual surprise, an experiment, a test carried out to better understand a given material or idea or concept, her recent show during ArtCity Bologna entitled Hardwork is certainly no different. Her work is a continual surprise for the spectator, who must always reevaluate what the artist is getting at on every level. I’ve known Letizia for a few years now, we met during our residency at Il Nuovo Forno del Pane at MAMbo in Bologna in 2020, but even after all of those months spent together I was never sure how to describe what she does as an artist. I would watch her constructing sculptural work out of wood and metal, out of textiles and plastics and I would search for a through line, a way to better grasp what she was working on. Calori’s recent show at Marktstudio in Bologna brought me to a deeper understanding of how a sculptor working today can work against certain traditions, taking feminism seriously but never too much herself.

Calori allows sculpture to have a sense of humor, to make fun of itself. Already by working with Marktstudio, a project first created by Giuseppe De Mattia, and under the artistic direction of Enrico Camprini and Chiara Spaggiari, Calori is signaling that perhaps her work, all artwork, is just that—work. Marktstudio is the window front and left side of a frame shop on via Don Minzoni, just steps away from MAMbo itself. Calori’s show which features a number of objects associated with work refuses a division of artistic and craft labor, here we see the artist making the tools of the trade and thus the trade becomes art.

Hard Work is a small show and gloriously respects the constraints of being in a very busy frame shop. Even passersby will see the show fully from the large window space. In front of the window on a low metal table Calori has placed three work shirts made out of wax. The shirts are made from a mold of shirts Calori’s father once wore to the office and that she later wore in the studio—shirts that never go on holiday. The button thread is made of a wick. The shirts are three different colors, deep blue, light blue and white; not only showing signs of wear but also the different ways work is classified—white color, blue color…somewhere in between. On the left wall of the shop Calori has placed four iron holders, each supports a tool made out of silicon: a hammer, a saw, a wrench and a screwdriver. Tools that are usually black or silver are in pastel colors. And they flop over, no good for fixing a damn thing.

When I walked into the show my first reaction was laughter, perhaps because I know Calori but also perhaps because I feel a lot like those tools these days—flopped over, exhausted, useless. Letizia and I have spoken on occasion about the complications of making art today and about working as an artist, but I wanted to expand that conversation in a more formal way. Since we both live in Bologna, Letizia invited me over to talk. I pedaled from one side of the city to the other in the forty-degree heat and she welcomed me with watermelon and the breeze of a fan. We spoke for a couple of hours about the show, work, art, life. And we also spoke a lot about feminism, because we always do. Letizia is a mother and an artist and having a show titled “Hard Work” feels extra loaded with meaning because of this fact. It’s all hard work, the art making, the promotion, the selling, the side hustles, the relationships, the mothering, the caregiving. To see work as represented by traditionally masculine trades and tools felt ironic as well, like Calori was somehow reminding the viewer of all the work a female artist must do, as well.

I asked Letizia a few specific questions because as excited as I felt about the show I wanted her to share some ideas more specifically here. Especially at this particular historical moment when work, and women’s work, is so often discussed and debated.

Allison Grimaldi Donahue: I’d like to start with the title of the show, which really orients everything: “Hard Work.” It would seem, in our society, what the artist does isn’t considered hard work—it is extra work, superfluous. How do you see this in relation to the works you’ve made? They are the tools of trade, they are the button-down shirts of businessmen, but they are soft, malleable, prone to breaking, melting away.

Letizia Calori: The works of the series Hard Work started appearing in my mind during the pandemic lockdowns, at a time where it was really hard to work and to keep it all straight, to continue doing your things, a time where the work of an artist was really not necessary, and I felt all my tools were all of sudden useless. All my stuff was there, taking up space, and I had to move my studio back home and all my tools were staring at me. Pointless.

And I felt a bit like those objects. My tools and the shirt I used to wear in the studio needed to take a different shape, a different use, they needed to become fragile, collapsed, grotesquely to the point of keeling over. They needed to lose the masculinity that they embody, to lose the strength, the power. They need to become inefficient.

“Hard work” also reminded me “art work”, if mispronounced as I would, which is at same time something that makes me struggle, but also something that, as you said, is often perceived as extra work and superfluous, but still takes a lot of energy and love and time. It is hard work but sometimes still feels “extra.”

Can you talk about the impulse to make this show and in this space particularly? Marktstudio does not have a gallery but rather they occupy an area of a frame shop. How did this environment influence the works or the show?

I am often triggered by the idea of showing or adapting my work into non-art spaces. The curatorial approach of Marktstudio in particular felt very right for the work I was doing at that time. I was reflecting on the symbolic meanings of the tools of trade and finding a way to play with and make some stereotypes ironic. The idea of showing the series Hard Work in a working space, run by women who are doing work that has historically been done by men, gave it an extra layer.

Moreover, I felt that showing the works in a frame workshop brings them in a liminal condition of being unfinished, like wares, or merchandise, that was emphasized by the installation in the window of the shop, and recalls the condition of the art work which is often in a strange condition between object and commodity, and the discourse around it.

I have the impression you are often interested in repositioning practical object, making us rethink their purpose perhaps, but even more so their symbolic value. What to you makes a given object loaded with value, what are your sculptural objects “loaded with” so to speak?

The objects I chose to cast and reproduce in silicon and wax are very connotated objects. They remind us of a male world made of hard work (precisely, ha), power, straightness, rigidity, hardness, functionality. They are objects that are very related to the body and the gesture, are things we use with hands and wear on our hip. They are objects that I had in my studio and that I inherited from father and grandfathers, so they are loaded with a personal and social stratification of a masculine understanding of labor. I needed to break from that, to make this idea soft, flaccid, distorted, and I need to see them collapse in order to take new shapes and meanings, to load them with a possibility of failure, with floppiness and a sense of dysfunctionality.

Speaking with Letizia was such a pleasure because though we use very different materials the words she spoke rang true to me and my understanding of artistic creation. At a certain point in our chat Letizia said that in the studio she just likes to “ciappinare” sometimes, and we laughed at this quintessential Bolognese word and tried to figure out what it means. The “ciappinaro” (or “ciappinara” in the feminine version) sits in his workshop and plays with tools, builds small things, doesn’t necessarily have a goal. Letizia said it’s a pejorative term: if you “ciappini” you have time to waste. But the more I think about it the more I love the term, and I love it for Letizia and her show Hard Work. There is nothing wrong with playing with the materials you have at hand, using the tools you’ve been handed down in new ways, experimenting, trying and failing and spending time contemplating how materials can carry so many histories. Hard Work shows us that some of the hardest work is soft and prone to breaking, fragile and delicate and in need of new vision.