Thinking in the Studio

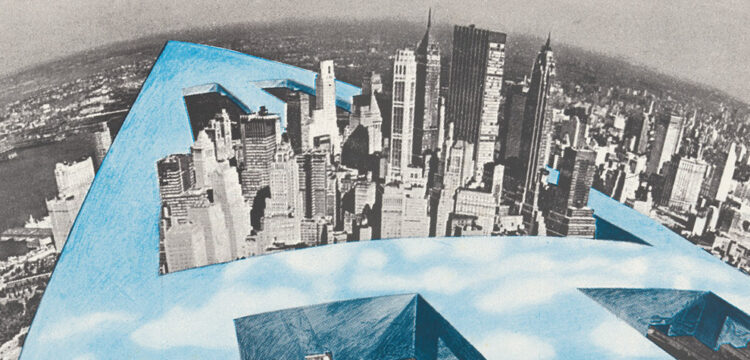

When the museum turned into an open space: Nuovo forno del pane at MAMbo

Il nuovo forno del pane is a studio space for artists and creatives at the Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna. The initiative was established by the city and the museum as Italy began to reopen into the post-Covid landscape this spring; over 290 artists living in Bologna (the competition’s only requirement was the place of habitation) responded to the call, and in early July the winners were announced. Artist Aldo Giannotti was meant to have an exhibition, Safe and Sound, at the museum in June, but given the situation he has also reimagined his involvement with the museum, and created the visual identity of this new project. Il nuovo forno del pane and its 12 artists will be in the space until the end of the year and will produce a variety of work, collaborations, and public programming.

“TAKE MY MEANING NOT MY INTENTION.”

Three sets of eyes on us at the moment. One set from up above, through a window from upstairs in the permanent collection. The other two from the sidewalk, from the shade of the portico, they even try to open the doors. Those doors are not the entrance to the museum and the spectators quickly notice their mistake and walk to the main door, but not without one last glance, not without wondering what is happening in this open, “to be determined” space. There are countless museums made out of the studios of famous dead artists. It is quite something else to observe living artists at work—the mystery risks banality, the magic artifice.

I’ve always been wary of the dead artist’s or intellectual’s space as much as I have been drawn to it. I question what it is that I am looking for. Many people claim they are searching for a trace of the deceased’s powers, a clue as to how their daily life may have affected their work: such romantic fallacy should no longer be encouraged.

MAKING ART MAKING BREAD

There are twelve of us in the large open space of the “Nuovo Forno del Pane”: Ruth Beraha (1986, Milano), Paolo Bufalini (1994, Roma), Letizia Calori (1986, Bologna), Giuseppe De Mattia (1980, Bari), Allison Grimaldi Donahue (the author) (1984, Middletown, Conn. USA), Bekhbaatar Enkhtur (1994, UlaanBaatar, Mongolia), Eleonora Luccarini (1993, Bologna), Rachele Maistrello (1986, Vittorio Veneto), Francis Offman (1987, Butare, Rwanda), Mattia Pajè (1991, Melzo), Vincenzo Simone (1980, Seraing, Belgio), Filippo Tappi (1985, Cesena). We each have our own socially distanced square in the former “sala delle ciminiere” complete with the remaining smokestacks and vaulted ceiling. This space was once a fundamental part of the bread baking factory constructed in 1917 by Bologna’s mayor during the First World War, Francesco Zanardi, to both employ and feed his struggling populous. The director of the Museo d’Arte Moderna of Bologna, MAMbo, Lorenzo Balbi, together with museum staff members Caterina Molteni and Sabrina Samorì, have created a new sort of factory, to support a different sector of the population in this very particular historical moment. The Warholian aspect of this project doesn’t escape anyone, I am certain. The studio is a place, at its core, that centers around production.

MAKING AND SHOWING

In Daniel Buren’s 1971 essay The Function of the Studio he writes: “the definitive space of the work must be the work itself.” In this essay he problematizes the places where the work of art resides, that is, the difference between its original home (the studio) and its destination (the gallery, museum, private collection) and he questions then, where the work truly belongs. His response, the work belonging to the work, seems obvious perhaps to those who make the work, but not in the wider world.

This particular version of the studio here at MAMbo puts this question into high relief once again, nearly fifty years after Buren wrote his famous essay. The work is born in the place of possible destination. No matter what the practice, the artist is aware of the space in which they create: a museum. First of all, this is a notably public space: our work can be seen from the street and our work can be seen by each other. Secondly, the Museum arrives weighted with history, both cultural and institutional, both of art and municipality. These factors affect both making and thinking—stepping into the studio is always stepping into a particular context. It could also be true that the in-between nature of the space pushes the work to reject a reliance on context, especially since this is a temporary space, ours until the end of the solar year.

ASSUMPTIONS OF SPACE

I don’t think I was quite clear enough earlier when I said we each have our own socially distanced square. The square is defined by neon tape on the floor. There are no walls. I’ve never worked in such an open space; on the second morning I dragged a bookshelf from the warehouse into my area. Already I am grounded. I learn what it takes, I learn how little it takes. What’s the difference who’s in charge: when our experience is increased by the addition of observations […] writes American poet Bernadette Mayer. When I stare off into space I stare into someone else’s work in progress or lack thereof (but it is often so hard to tell the difference). The background sights and sounds of the open studio invite the accidental; the work of the other whom I have just met suddenly becomes much more likely to fall into my work, organic matter into the vat.

SEEING WRITING

Each artist brings materials to the studio, some little by little, others with one vanload. At this point the space and objects are arranged and rearranged to find a way of working, one way of working among many to come. Here I am writing to you under the buzz of a drill, a lot of laughter and the vibration of a wall. Matter is being changed and altered. Ann-Sophie Lehmann discusses the practice of British sculptor Sir Anthony Douglas Cragg: According to Cragg, his ideas do not occur prior to material creation, but are themselves a kind of material, like wood, stone or plastic — or the artist himself for that matter: “As soon as I look at any material, I combine my thoughts with that material, and so I’m changed because I become influenced by everything that’s around me.” I’ve long held the belief that words are objects to build with. Not only does this help me to be less precious about my writing but it changes the very practice of writing itself. Like in all of the other arts, the writer borrows and steals, molds and glues, tears apart and puts back together. Ideas and language can be more clearly seen as the matter they are when placed in the context of the studio. Pass me the saw, pass me the soldering iron.

ART CRITICISM

It is about writing with the work. Traditional criticism seemed so often to write against the work it will take years to change the precedent. The art writer can write from within it, beside it, while in the company of the work. Art writer Thyrza Nichols Goodeve talking with art writer Jarrett Earnest, I’d go back to what I’ve said earlier: the process of writing about art is closest to the process of writing fiction, because it’s about discovery. not knowing, trying to build a coherent world from the unfamiliar, from the edges of what one barely understands or knows.

This too, was Carla Lonzi’s dream, or at least how I see it. She was with the artists in Autoritratto, on a quest, searching. What she didn’t find, and perhaps part of the reason for which she had to leave the art world, was room for this way of thinking during her own time, this way of thinking that valued curiosity and poetics over traditionally academic means of discourse, a way of thinking that considered the art writer a creative person rather than an examiner.

TOWARDS AN ONTOLOGY OF OBJECTS

Much academic thinking has, for the last century, focused on language—the “linguistic turn.” Interest in the studio offers an opportunity to rethink this trend and move towards the “material turn.” The product, whether a work of art or a piece of writing only emerges from co-existence, two or more entities coming together. As feminist quantum physicist Karen Barad writes: The very nature of materiality is an entanglement. Matter itself is always already open to, or rather entangled with, the “Other.” The intra-actively emergent “parts” of phenomena are coconstituted. Not only subjects but also objects are permeated through and through with their entangled kin; the other is not just in one’s skin, but in one’s bones, in one’s belly, in one’s heart, in one’s nucleus, in one’s past and future. Our work will change and we will change through these months of working together and likely in many ways we will never notice, or not for a long time. It will be a constant rebalancing, a continuous reconstitution of work and self.

The studio allows for whatever your pace of thought on a given day. The studio as paradigm and place has far too much to teach us but thankfully, we are here to learn. There will be ample space to figure out what this iteration of the studio means both through the works and through the artists and guests who come to visit. Already the twelve of us are finding ways of coming together. We find areas to rest, to make a mess, to ask questions. Over too much coffee we discover which philosophers we want to invite to speak, which artists we want to learn from. And over the next six months new problems will emerge and new materials and friendships will be forged often in accidental moments when it is unclear whether we are making the work or if the work is making us.