Tales From the Gutter

Martin Wong’s “Malicious Mischief” at KW, Berlin

Curated by Krist Gruijthuijsen, Agustín Pérez Rubio, with the assistance of Sofie Krogh Christensen, Martin Wong’s Malicious Mischief at KW is the artist’s first anthological show in Europe. It showcases over three decades of Wong’s painting production, from his early years to his premature death from an HIV-related illness in 1999. In my opinion, one of the most interesting shows I’ve seen in years.

This exhibition is also the result of the joint effort of 4 international institutions: Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo, Madrid; KW, Berlin; Camden Art Centre, London and at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam. Martin Wong’s work is still very little known outside the USA, so these four iterations increase the chance to get to know his life and work. Moreover, I’d like to compliment the KW’s curators and the whole staff for conducting its public program, which weekly offered opportunities to further study and debate the work of this great and still little known artist.

The first room of the show introduces us to Wong’s early production, from his young years when he was part of San Francisco’s queer community. This first documentary room is filled with drawings, sketches on paper and polaroid shots. These documents also support the presentation of his first three relevant works, made out of ceramics: Untitled (MW Was Here January 23 1970) 1970, Love Letter Incinerator ($), 1971, Untitled (Coyote), 1970. The curatorial team has decided to present these pieces on the first table, together with the materials mentioned above. These ceramics are relevant because they reveal already meaningful aspects of his approach to art-making. The clay is dark and heavily handled, and the surface is vibrant, organic, almost alive. These works are not glazed nor colored and their subjects are highly influenced by daily life, cartoons and comics. We see something like a monstrous puppet eating a safe, some sort of strange sci-fi portal, and a coyote. The clay is dark red, heavy and metallic. Still, the most interesting trait of these works is the vibration imprinted with fingers on the surface and their strong impressionist quality.

In the same room we can see one of Wong’s first juvenile paintings: Costume study from the Angels of Light “Peking on Acid” Performance (1970). Here the artist paints a mask with some decorative elements graphically organized around it in a dynamic composition. Remarkably, this early painting already features a black background—a stylistic choice he will keep during his career, a recurrent element in almost every work in this show. Dark backgrounds have a long tradition, especially from baroque times on. This tone of black reminds me of Gustave Courbet, whose work can be admired not far, at the Alte Nationalgalerie.

The following room is transitional, and it features another early work titled Tibetan Porky (1975-78), where Wong seems to represent an ironic version of the deity Māra, the Death or the Devil, while ironically eating a watermelon. The three eyes and traditional skull crown and necklace give hints towards this specific character of the Buddhist tradition, known for visiting Buddha during his meditations and trying to lure him off his state of acquired perfection and bliss. Along with motifs of the Buddhist tradition such as the skull, we find some details borrowed from classic Americana post-war period, like round chess pads. Even if painted in a juvenile style, this mid size work introduces us to the continuous cultural mashup that will inform all Wong’s production and define his aesthetics of artistic appropriation. In his paintings subjects and motifs coming from traditional Asia and vernacular Americana mix and blend with surreal irony and metaphysical melancholia.

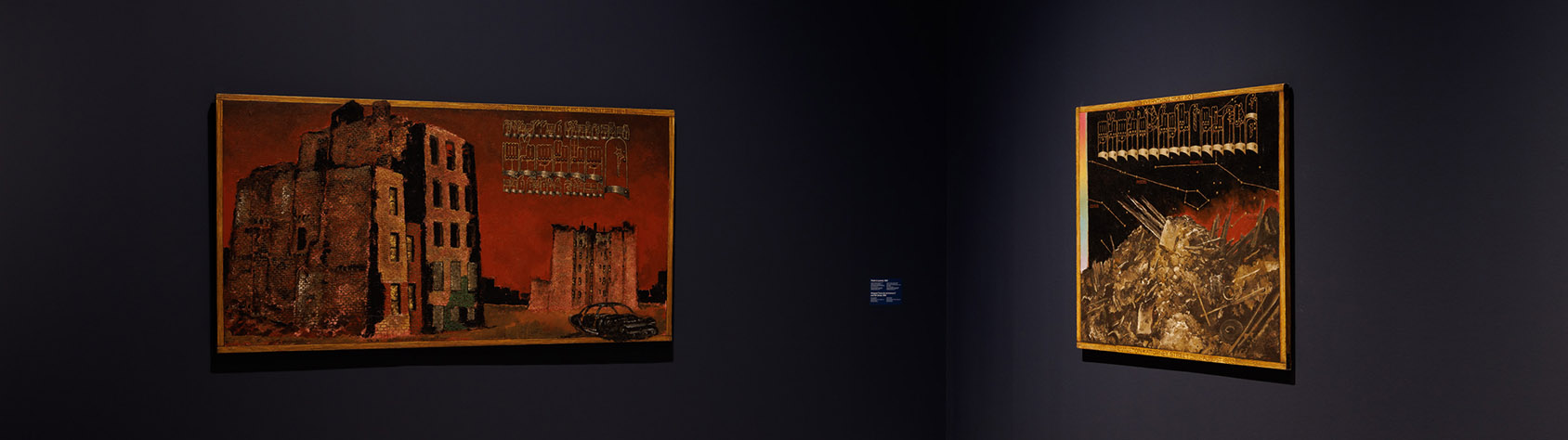

– Malicious Mischief at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin 2023; Photo: Frank Sperling.

The show continues with a self-portrait, for me one of the best pieces in the show. With a small format and unharming simplicity the artist represents himself with a cowboy hat, appropriating and queering the most American of the clichés. His face is cheeky, his skin is shiny and reflects a strange green light. The style in treating light seems to borrow from airbrush art, which was common in 1950’s Americana design culture. In the lysergic reflections of the sky in Weatherby’s (1974)—a small landscape painting of a street of Eureka—this reference seems to be even clearer.

In the following room we can find two mid-sized squared paintings: Untitled (Jesus tattoo), (1978), and Divine, (1979). Two bust portraits, one from the front and one from the back: in one of the two we recognize the queer icon Divine, whose traits we can only vaguely grasp. The painting seems to be left unfinished, with a first layer of okra laid over the black background, with some brushed shades and lights appear here and there, incomplete, as washed away by time. Here Wong shows skills and irony, as his usage of color recalls antique buddhist frescoes he might have seen during his formative trip to Nepal. The characters are illustrated similarly to traditional Chinese drawings, in their exaggerated proportions. Here Wang also introduces the stucco background he will use over his entire production, as clearly visible in almost every painting in the show. I find myself amused by thinking that Wong—with this combination of acrylic, stucco and black background—seems to be reproducing a sort of artificial oil painting, mimicking its profundity and preciousness with much cheaper and faster materials.

A bigger format painting Tell My Troubles to the Eight Ball (Eureka) (1978-81) wraps this section, featuring an 8-ball floating on red clouds, again mashing up American and Chinese motifs. These red clouds—traditionally hosting deities—here support a Magic 8-ball: a fortune teller game invented in Cincinnati in 1946. In this painting we find again the stucco background, that in combination with the black defines his unique style. I find myself amused by thinking that Wong—with this combination of acrylic, stucco and black color—is forging an artificial oil painting, mimicking the profundity and the preciousness of oil, with much cheaper and faster materials.

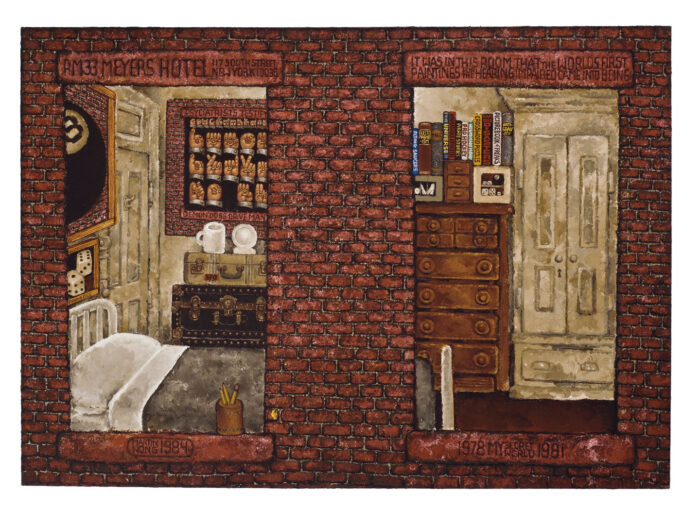

From this point, the show just becomes more and more compelling. The first of the following rooms features two mid format paintings with two views of Wong’s apartment room in New York where he moved away from the West Coast: Voices (1981), and My Secret World, 1978–81 (1984). The room they portray is modest but neat, all the elements are well organized and composed. Our attention is brought to the details, such as the dusty brick walls, the old white mattress, the title of the books on his shelves. Everything is silent and tidy, the artist is melancholically absent. Wong is clearly a traditional painter, and these curated interiors not only display his humble lifestyle at that time, but in their idealized composition they initiate a conscious dialogue with the history of art and the tradition of portraying the artist’s studio.

In the same room, another smaller painting named Psychiatrists Testify: Demon Dogs Drive Man to Murder, (1980) introduces another visual motif borrowed from sign language. After meeting a deaf man in NY, who gave him an informative card about deaf language, Wong started to embed encrypted messages in his paintings interpretable through sign language. Touchingly, this decision really shows the profundity and complexity of Wong’s work, who always placed marginalized communities onto the stage, be them disabled, queer or outlaws.

The show features many paintings with these encrypted motifs, very graphic, mostly resembling manuscript pages. These alphabets also echoes traditional Chinese art, as it often includes calligraphy and printed banners on the sides of the drawings. Also, deaf and sign language might also reference the sign system used in the ghettos of New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles to identify among gang members. This idea of coding and decoding appears fundamental in Wong’s work—whose references span from the most arbitrary and vernacular to the most ancient and traditional. With irony he provides encrypted rebuses and with nonchalance—often in corners, close to the edge—their translation or solution.

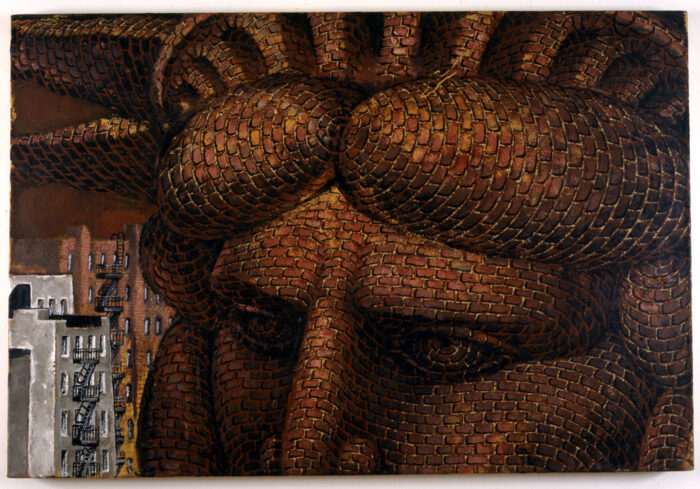

Downstairs, the main hall of KW is divided into four areas. In the left wing, we find big format paintings, featuring constructed landscapes of the city of New York. We can see how Wong’s mastered use of stucco perfectly matched his interest for the rusty metal surface surfaces and the ruvid brick walls of New York City. In Nocturne at Ridge Street and Stanton (1987) Wong provides a complex perspective view of the street of Loisaida. On the foreground, red bricks, some white bricklayer windows and a close facade. On the left our eye travels to the other buildings of the street and into the black sky illuminated by the city lights. These facade walls appear highly vibrant and alive. In an impressionistic manner they capture light, movement and texture with visible brush strokes over the irregular surface of the stucco.

To my surprise, the style of this and other cityscapes recalls the magmatic consistency of the water as painted by Gustave Courbet, in his Waves series painted between 1869 and 1870. Over time Wong’s palette stayed consistent, with some black always applied over the stucco, and over the black only few other colors such as red, brown, white and okra. In the black night sky sometimes gold appears, tracing lines of constellations, in delicate contrast with the brute materiality of the New York’s brick facades, as to manifest the artist’s interest for the cosmic and the spiritual.

Even if the painting style owes to impressionists, these images are not made en plein air. They’re instead carefully planned with preliminary studies and photographs, collaging and collapsing elements of different origins. In his paintings, Wong builds an artifact version of the suburbs of New York City with cars on fire at night, old torn down buildings there to make space for new constructions. In this series of cityscapes, human figures appear only at the margins of these landscapes, like in Exile – This Night Without Seeing Her Passes Like an Eternity (1987-88), where the only figure partially visible seems to be caught in a sexual act. Sometimes they materialize like small melancholic figurines, silent and lonely in the majesty of the city, as if in No Es Lo Que Has Pensado… (It’s Not What You Think…) (1984). In these landscape works, hand sign language is still present in the corners or against the sky, anticipating or following an event, a story we don’t see yet we can fantasize about. Our mind wanders and our heart is moved by this melancholia—by the affection he stages, depicting his parents in Chinese Laundry (A Portrait of the Artist’s Parents) (1984), in the reconstruction of their first encounter in a Chinese Laundry Shop in San Francisco.

Indeed, Wong’s paintings depict with extreme care and realism the emotional landscape he’s inhabiting. By bringing extreme focus to the textures of rusty and dusty surfaces, he portrays time and decay. Its impressionist brush strokes transmit a vibrant emotional quality, while the black background transforms every scene into a night scene.

This becomes apparent in the following room which reconstructs Wong’s exhibition The Last Picture Show at Semaphore Gallery, (1986). A series of large paintings of shutters and entrances in the streets of New York lay on the floor, from there up to two meters high, giving us an immersive experience into the city’s slums. Their scale is ambitious as the relation is almost 1:1 with the viewer. No figure appears here either, but looking at visitors walking inside this room, we understand they’re part of these paintings themselves, like characters in a play. Also, the combination of simplification, the impressionistic quality that animates the surface and the extreme flatness all together reminds me of a background of 1980s video games.

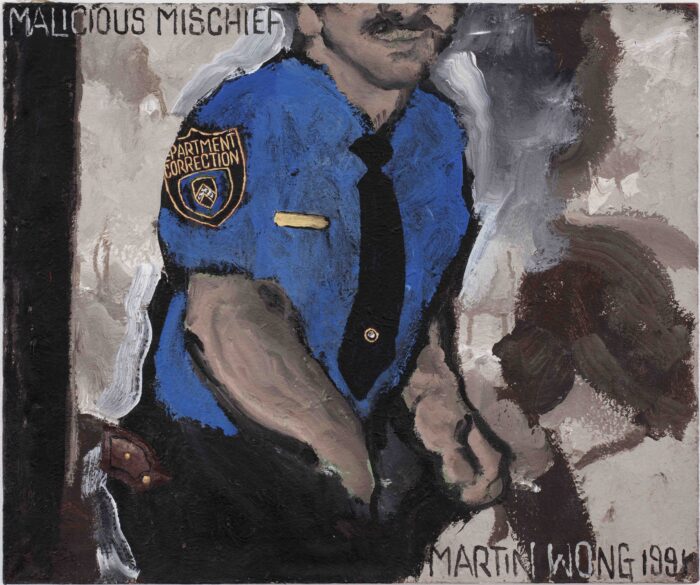

In the second-last section of the show figures and figurines finally take over the stage, and we get to know his community, the inhabitants of the neighborhoods we just saw depicted in his fabricated cityscapes. For years Wong masterly chronicled the life of those like him, living at the margins. From landscapes to brick facades, we now see the grim interiors of a department of correction. In the almost black Prison Bunk Beds (ca. 1988-92), or in the small sized hexagonal Sacred Shroud of Pepe Turcel (1990), Wong journals the hard life during conviction, a frequent experience for his peers, as criminals, drug dealers, poets and graffiti artists.

In Lock-up (1985) a figure is sleeping in a caged bed, his friend artist and graffiti writer Sharp (Aaron Goodstone). Details such as the paper texture of an erotic poster or the coldness of the metal of the bed frame evoke strong physical feelings. Come Over Here Rockface (1994) reveals again Wong’s irony: here, power dynamics between convicted and surveillant are reversed into an homoerotic game.

Notably, these paintings still present the same reduced palette of Wong’s whole production: black, white, red, brown, gold, and mint green. With the same reduced possibilities of a renaissance painter, Wong fabricates his own classicism, using the color scheme which he borrows from buddhist art from Himalaya, with a dominance of shades of red, paired with black, white, night blue and mint. Moreover, the rudimental use of perspective also references the austerity of late medieval and early renaissance representations, where composition is used to reflect meaning and hierarchy.

With its bright yellow background the last section tells us the story of Wong’s return back home after his years in New York, after he has been diagnosed HIV positive. Here, the painting Grant Avenue, San Francisco (1990–92) stands out in its complexity and scale. In this large format Wong opens a window on the Chinese community of San Francisco. The use of the vertical format allows him to express transcendence, to connect the streets to the sky, the mundane to the spiritual. At the bottom of the image, we see his typical style of portraiture which characterize his subjects almost as cartoons or figurines—similar to what would be called Puppets in graffiti culture.

A Chinese woman (his auntie) walks toward the viewer. Two male figures seem to look at her bum. One of them eats an ice cream, making the whole scene a funny cliché. Wong reconstructs parts of San Francisco Chinatown’s buildings. We see elements of a bazaar and of the Far East Café. A lantern decorated with dragons lights the streets from the top of a traffic light, Asian-styled mint-green roofs, peak in a dense crimson sky. The brushstrokes are impressionistic, but the same unreal artificial light gives a real sense of profundity. Also, all his surfaces are independent and flattened to the vertical plane of the painting. I believe the power of his images resides just on these two main features: impressionistic surfaces and flattening perspective, qualities that reminds me of early video games, which in their low pixel resolution and simple animations also have some impressionistic quality. Moreover, as Wong’s paintings, early 2D graphic engines never rendered a proper threedimensional space.

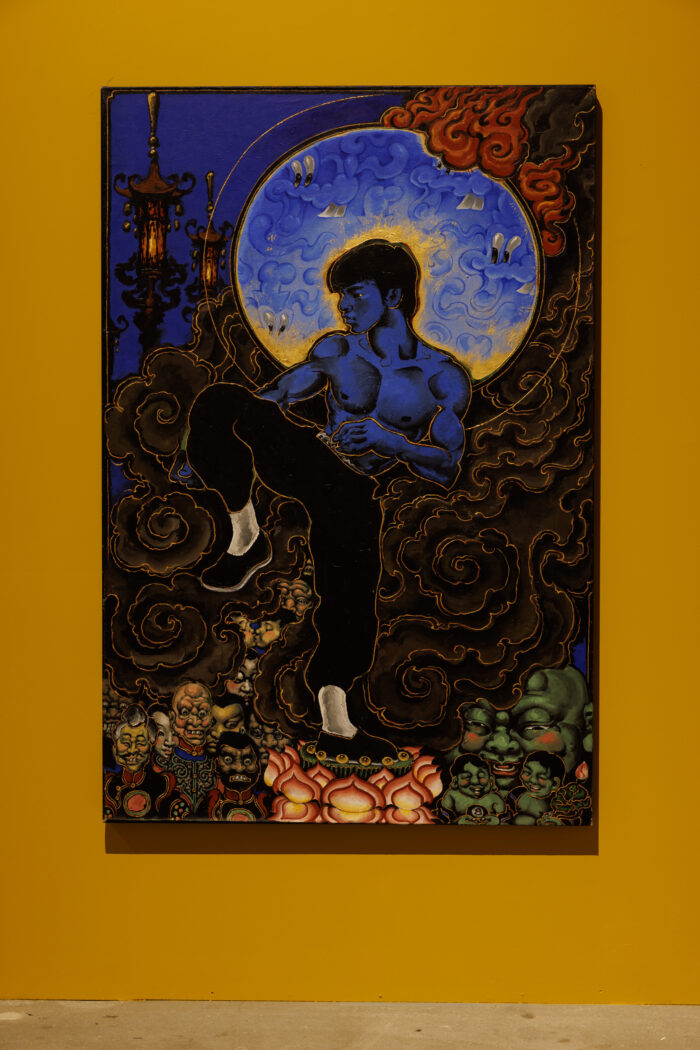

The quality and vitality of this last production is striking. In Bruce Lee in the Afterworld (1991) there’s no fear of death, as the blue-skinned Hollywood star stands out fiercely like a deity over small demon-like figures below. His blue aura shines into gold circles. The clouds take the form of a spirit, the Disney’s character Goofy. His last painting Did I Ever Have A Chance? (1999) wraps the show. Realized in his hospital room, this last work reconnects with the cultural clash of his early works. On the top part of the image, he writes in gold—“Did I ever have a chance?” Underneath, he paints a blue Patty Hearst as a Kali, the Hindu goddess of death and time. She’s adorned with snakes, heavily armed and ready to fight.