The Imprisoned Cowboy

Bruce Nauman at Punta della dogana

Bruce Nauman: Contrapposto Studies is curated by Carlos Basualdo, the Keith L. and Katherine Sachs Senior Curator of Contemporary Art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and Caroline Bourgeois, curator at Pinault Collection. The exhibition is an homage to one of the major figures of the contemporary art international scene and focuses on three fundamental aspects of his oeuvre: the artist studio as a space where creation takes place, the body through performances and the exploration of sound.

Organized at Punta della Dogana and curated by Carlos Basualdo and Caroline Bourgeois, the big retrospective exhibition dedicated to Bruce Nauman already starts before the entrance of the museum’s building. The first work is a sound piece installed inside Sotto Portico dell’Abbazia, where a regular visitor can often find a curious street artist playing some sort of ancient lute, dressed in a white and fluffy shirt. Instead of that beautiful and ancient sound, Nauman sets his first intervention with the deconstructed harmony of the piece For Beginners (Instructed Piano), 2010. Realized in collaboration with the musician Terry Allen, the piece appears like an arbitrary sequence of notes, played with strong rhythm, with moments of assonance and dissonance, pleasing and then frustrating the listener. It’s one of those pieces that need your attention for awhile to be able to fully experience the wide range of emotions it can suggest—making one feel bored, excited, silly, and longing for more. The notes are indeed arbitrary, as the score is actually a transcription in music of another work by Nauman—For Beginners, where a huge projection shows two hands performing all the finger combinations possible. With a minimum gesture, Nauman takes the place of the nostalgic lute player and introduces us to his aesthetic world made of boredom, fun, discomfort and pleasure.

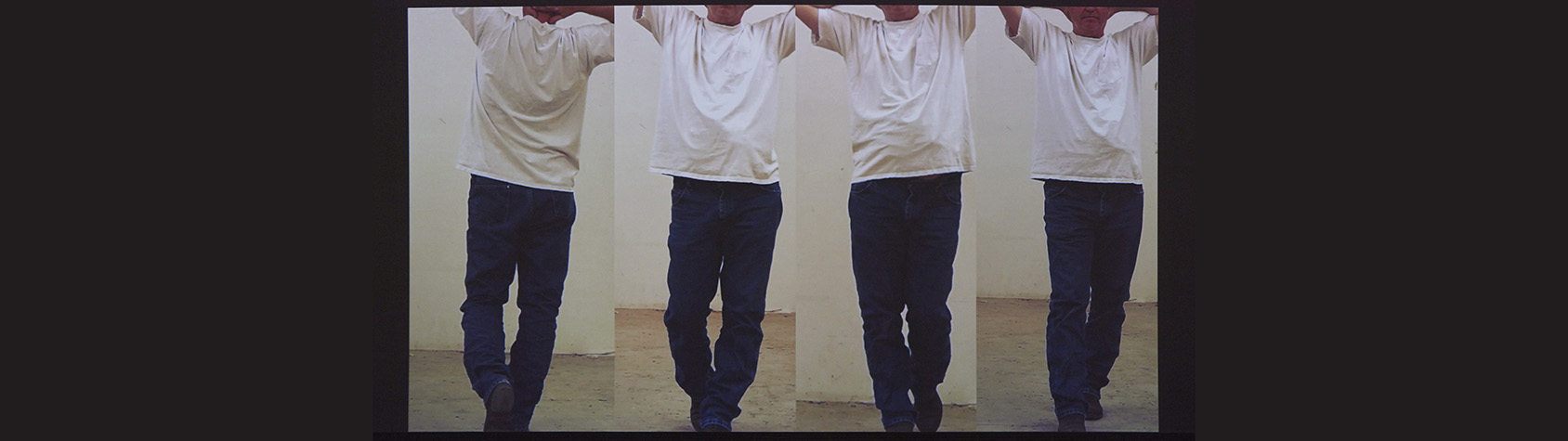

The exhibition continues inside Punta della Dogana and presents, in the first two big halls, two monumental video works: Contrapposto Studies, I Through VII, 2015/2016, where he goes back to—and explores with novelty—the ideas that led to Walk with Contrapposto, many years earlier. Notably, Nauman wears almost the same clothes he was wearing in 1968, a white t-shirt, some blue jeans, and cowboy boots: the dress code of the West American suburbs. The boots creak and slam, giving rhythm to the video which is deconstructed with clips in play and reverse. The figures are also cut in half horizontally, and the two parts proceed autonomously, sometimes lining up, sometimes not. Nauman is simply going up and down, at a certain speed, holding a specific posture. His gaze is absent, as if it would be deprived of any subjectivity.

In the following room, three works from 1969—two titled Untitled and one Untitled or Extended Time Piece—express the conceptual nature of these performance pieces, which are conceived as tasks or instructions, written with a typewriter on an A4 sheet. One of these sheets hangs on the wall, yellowed by years and ripped on the side. On the corners of this passage room three performers execute Nauman’s performance pieces. Two of them are busy executing Bouncing in the Corner, and one cannot avoid noticing a big hole on one of the drywall corners of the room, almost at shoulder height.

In the following room, with the lights turned off and the windows obscured, we can look at the video work Walk with Contrapposto, 1968, looping on an exhibition monitor. The exaggerated posture, forced into a narrow corridor can remind one of Michelangelo Buonarroti’s Schiavo Morente at Louvre, because of the posture and the compression effect between the softness of the body and the rigidity of the stone that contains it. As the title suggests, Nauman is interpreting the contrapposto formula, a formal solution used by the ancient Greeks to distribute weight inside the sculpture so to solve the problem of balance, in a figure in movement.

The problem of the tension between opposites—that is an inherent problem of the moving figure—is present in all Nauman ouvre, and is strongly conceptualized by the artist and can be used as one of the possible traits d’union to read his work at large.

Walking into the following room, we can see how this idea is turned into a praxis in many variations and applications—polarizing gestures and creating the necessary physical tension to sustain the endurance tasks in which he put himself. Revolving Upside Down, 1969, shows us that this is a necessary means. The artist, dressed all in white and with his usual cowboy boots, is standing on one leg and bending forward, extending the free leg backwards to find balance. Using his standing feet he executes a circular revolving movement. When the position becomes unbearable, he straightens his bust and extends the other leg out in front, finding the momentum for a new pose, and another rotation.

The repeated staging of the videos in the artist studio, and the strong sound component of these introduces us to the second part of the show where specific relations between action, sound and space are enquired. After a brief of detour in the panoramic rooms designed by Tadao Ando, the exhibition path takes us to Steel Channel Piece, 1968, an enigmatic sculptural collage featuring a U-section iron beam, with a loudspeaker mounted on one side and connected to a tape recorder installed nearby. The audio features all the anagrams of “lighted steel channel”, as it is trying to make fun of the gloomy sculptural arrangement that in turn alludes both to industrial architecture and to the function of regimentation of the bodies through the use of speakers, like one can find a in a factory or prison. As in Walk With Contrapposto, the architectural elements have a specific relation to the body that is sometimes subtle and indirect, sometimes more active and compelling.

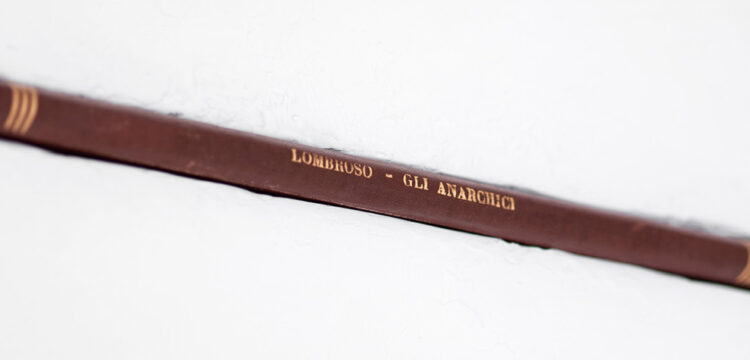

In the following room, on a wall size video projection, we can have an extensive look at the artist’s studio in the night with Test Tape Fat Chance John Cage, 2001. Again asking the viewer to actively pay attention and wait, Nauman’s studio is revealed to be inhabited by nightly figures: mice and cats. Even if at first glance this might appear accidental, and the mice race a mimic of Tom and Jerry’s cartoon, Nauman is setting again a stage where actors and figures develop relations of power. If over the years Nauman seems to elaborate this theme in his work, so definitely did the philosopher Michael Foucault, whose main work Surveiller et punir: Naissance de la prison, published in 1975, draw upon Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon—a newborn paradigm of disciplinary control. The peculiar relationship between architecture, acts of imprisonment and control through visibility, he states, can be seen as the main example of how power operates within modern society and has shown how much subject exposure and visibility are related to control, and how the relation between body and architecture can be read in the disciplinary terms of incarceration.

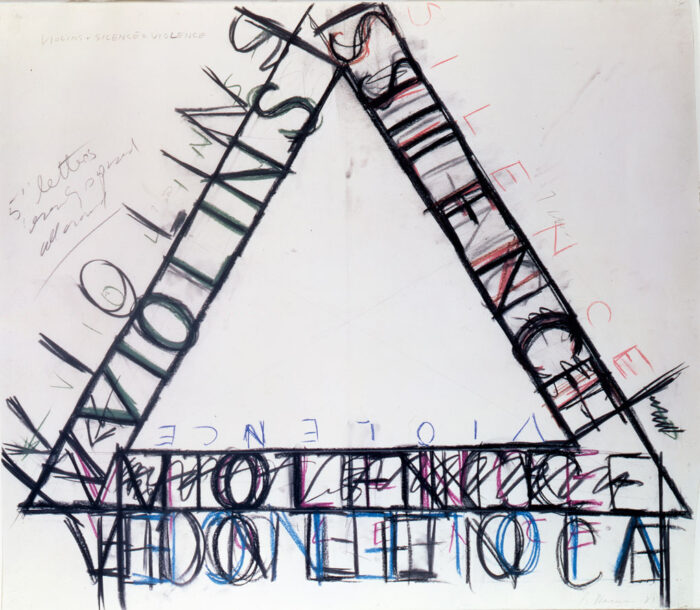

The title of the big drawing Violins+Silence=Violence, maintains the tension high, exasperated by the use of the triangular shape suggesting together with the handwriting a sense of extreme discomfort. The exasperation of the vectors, the obliqueness, are a recurrent quality in Nauman’s work, and we can find the same skewed perspective of Walk with Contrapposto in Diagonal Sound Wall (Acoustic Wall) where a soundproof wall cuts the space of the room, making the viewer walk on the far right of the room to reach another wall installation: Acoustic Wedge (Mirrored), 2020. Its acute shape also seems to recall the wedge shape of Punta della Dogana, intertwining the experience of the piece to the experience of the museum architecture. Once inside the installation, the sound is highly deprived and one can easily experience a surprising sense of vertigo. And if a visitors would have lost balance and faint because of that sensory deprivation, they would probably be found on the floor, lying down like in: Elke Allowing the Floor to Rise Up Over Her Face, Face Up,1973, and Tony Sinking Into the Floor, Face Up and Face Down, 1973. In these two video pieces, again the camera catches the figure diagonally, stretched out on the floor. The use of the figure is so peculiar, that Tony can definitely remind of the lying figure of the slave in Tintoretto’s Miracolo dello Schiavo, 1548, that can be seen not far from Punta della Dogana, at the Gallerie dell’Accademia. The endurance performance of Tony lasts almost an hour, but eventually he starts to choke, the recording has to be stopped, and the video ends.

The space that Nauman represents in his works does not follow the codes of the modernist gaze that uses central perspective as a tool for knowing, and ultimately conquering space. It seems to be closer to the exaggerated perspectives of medieval times, where everything is skewed, forced, and psychologically distorted. In the Sound Breaking Wall, 1969, behind a wall we hear a voice laughing, someone breathing, somebody else hammering. The torturer, the tortured, and the breakout.

Over the years, Nauman has shown us the dark side of modernism, its distinct function as a technological apparatus of power, and its subtle purpose of entanglement with body and mind. As a contrapposto, sounds and words are used as tools to dissolve meaning, create holes, escape routes and draw ways out. One of the closing pieces of the show, Nature Morte, 2020, presents three projections of 3D scans of the studio of the artist. The mapping is most likely realized with a hand-held scanner as it presents so many details inasmuch as missing parts and black holes, from where the unknown and the untold penetrates the cold logic of the scanning machine. For the frontier cowboy, wearing jeans and boots, the studio is a stage for liberation as much as it is just made of barriers and cages, showing us how good we are at building our own prisons, and how we may break free.