Speculating Alongside the Tigers of Tamil Eelam

On Christopher Kulendran Thomas’ exhibition at the ICA in London

The exhibition Christopher Kulendran Thomas: Another World at the Institute of Contemporary Art, London, enlightens us on the lost cultural legacies of the Tamil Eelam independentist movement through the high-tech video installations The Finesse (2022), Being Human (2019/2022), architectural drawings, AI-generated abstract paintings, Tamil ceramics portraying queer love, and the oddly visionary research community project Earth. Touching upon Tamil Eelam art, architecture, and technology, the dialogue that unfolds in-between the exhibited works leads us to urgent and radical debates on “such things” as democracy, diasporic communities, cooperative economies built on renewable energy and computational coordination, the imagined nation-state, and power relations in the media.

Crossing the lower gallery’s heavy curtains of the Institute of Contemporary Art in London, you find yourself in the lushest jungle. On one side, a wall-size screen projects the depths of a heavy forest. On the other, a smaller assemblage of five juxtaposed panels is playing archival footage of a combatant speaking from the back of a military tank, seemingly driving through that same forest. “History is so much more complex than this linear idea of progress” she states, “this is why we invited you to come here, so you can see the new society that we’re building with your own eyes and not through Western propaganda.” The combatant in the footage belongs to the militant group the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam – LTTE, and the tank is traversing the Vanni forest in the northern region of Sri Lanka, the long-time home of its Tamil minority and battlefield of a 26-year civil war ended in 2009 with the defeat of the de-facto state of Tamil Eelam. In the video installation The Finesse (2022), commissioned for the exhibition, the artist of Tamil descent Christopher Kulendran Thomas displays a groundbreaking conversation between the LTTE Tiger Manmahal, a group of other artists of Tamil diaspora descent, and a CGI (computer-generated imagery) avatar of Kim Kardashian on the lost cultural legacies of the Tamil Eelam independentist movement, touching upon their art, architecture, and technology, leading to urgent and radical debates on reenvisioning “such things” as the nation-state, democracy, and power relations in the media.

“Look at this jungle; it’s a complex network of countless interdependent species. The earth here is an intermediary that processes all the tensions,” continues Manmahal in the footage, “like a giant biochemical computer.” It was indeed the mid-90s when the LTTE started to visionarily explore the potentiality of the newborn Internet. They used it to create an independent network of news and space for debate and relevantly to manage a self-sustainable parallel economic system among the Tamils and its diaspora, including the remote citizens in the decision-making processes. As Maya Ranganathan first wrote in Nurturing a nation on the net: The case of Tamil Eelam, websites such as tamilnet.com, teedor.com, and the now-defunct original eelam.com aimed at spreading the Tamil utopia globally. They nurtured sentiments of nationhood and built on the virtual state of Eelam an out-and-out imagined community beyond the control of the first Silicon Valley new media industries. Drawing from an ongoing issue in media history, the disappearance of eelam.com implicated the loss of an archive of revolutionary content, an erasure of collective memory that happened even more recently when Instagram hid Tamil-related hashtags; and Spotify removed Tamil Eelam music.

Reflecting on Tamil technology, erasure, and the erasure of Tamil content online, one of the filmed artists of Tamil descent, Amina, refers to the Sri Lankan civil war as partly caused by the problematic imposition of the Western model of the nation-state on postcolonial societies. “The challenge for any representative democracy is that you need a shared idea of ‘truth’, a shared fiction that’s backed by the state,” argues Amina. “Historically, this is why the rise of nation-states coincides with the advent of broadcast media.” And then, speaking of the free circulation and asymmetrical centralisation of media stories, there it appears: O.J. Simpson during the 1994 process aired on a TV in front of Manmahal. Questions arise. Who owns then the right to write where the “truth” is? How do you know if journalists distort reality? Asks the American interviewer in the archival footage. “Reality, ayo, reality,” firmly comments Manmahal while watching the O.J. Simpson process, “reality is a story that empires perpetuate by fixing one particular fiction as the ‘truth’.”

Indeed, the American media industries that shaped the collective fiction of justice around the figure of O.J. Simpson are the same that, in the wake of the War on Terror, narrated the independentist LTTE as a terrorist group that the Singhalese majority had to defeat to find peace and democracy. Here is where the CGI avatar of Kim Kardashian—whose father, Robert Kardashian, of Armenian descent, famously participated in the case as OJ’s defence lawyer—has a say. “I feel like us Armenians know that nothing can protect you when the narrative goes against you,” states my new favourite version of Kim Kardashian. “And not just Armenians—Kurds, Tamils, Palestinians—any people who’ve, you know, ended up on the wrong side of a geopolitical narrative.” Amid all the various fictions told around them, the artists of Tamil descent filmed by Kulendran Thomas agree on how they ended up making sense of this fragmentation by accepting that part of being Tamil was ultimately to blur the lines between “reality” and “fiction.”

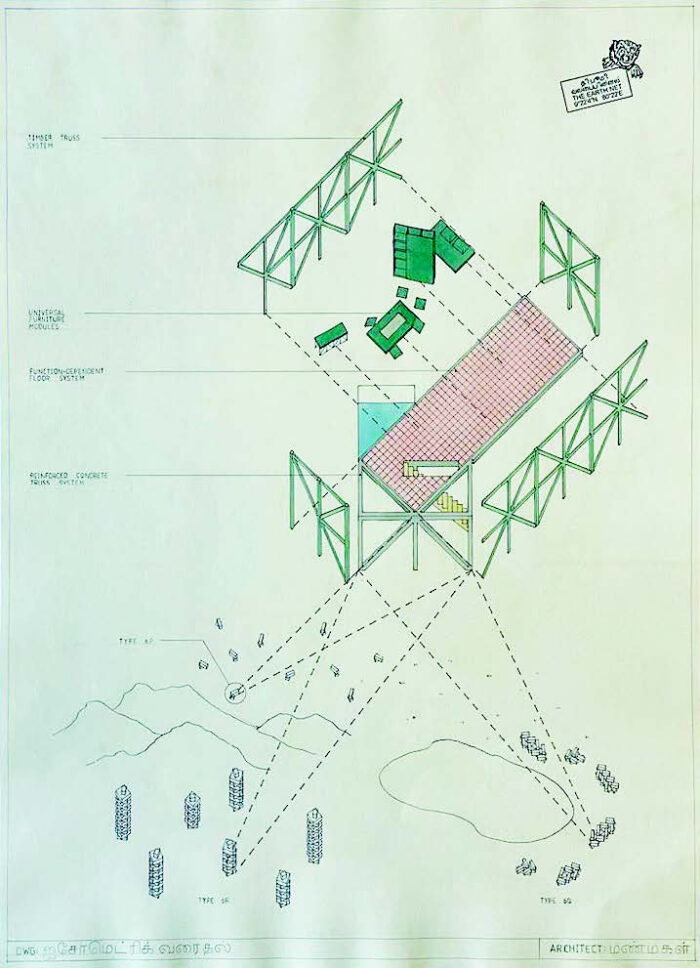

A series of vibrant and oneiric exploded-view architectural drawings hang on the wall down the hallway of the lower gallery. As with the parallel networks underpinning the Tamil Eelam Internet, the LTTE, influenced by the soviet disurbanist school, was also committed to understanding architecture as a question of political science, a tool for re-imagining society and exploring different ways of organizing themselves in flexible housing. “Our people were a network before we were ever a nation,” says Tiger Manmahal, first trained as an architect, “our Chola Dynasty stretched from here to China. It was an empire with no territory, a sprawling collection of guilds.” In her eyes, it shines the vision of an experimental society that allows interdisciplinarity and mobility beyond Western binaries. “And our pulavars… There is no word for pulavar in English because you don’t have such a concept.” She says we could say “artists,” but they do much more than what the word ‘artist’ means to us. “A pulavar might do art and do diplomacy and do military strategy,” and do the computer engineer and the architect. She says they were not constrained to one field but rather would move between them, “art was really at the heart of Tamil resistance.”

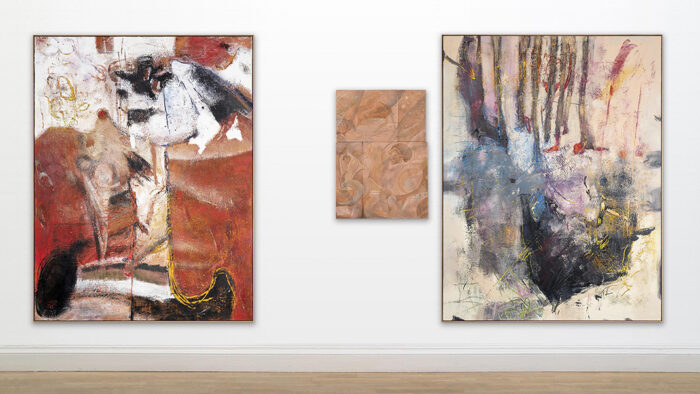

Moving to the upper gallery, familiar yet anonymous big-size abstract paintings hang together with ceramics by the Tamil artist Aṇaṅkuperuntinaivarkal Inkaaleneraam. The jarring contrast is on purpose. During the brief economic boom that followed the revolution, Western art galleries proliferated in Sri Lanka and, with them, their artistic canons and neoliberalist logic. The exhibition’s artist Kulendran Thomas witnessed from London, where he grew up, the aftermath of the defeated revolution, his family’s homeland of Eelam being wiped out and with it its artistic legacy. He observed from afar what resulted in a generation of Sri Lankan artists imbued in Western aesthetics, assimilated by white cube commercial art galleries and a newborn biennial. In response to it, the (purposely) boring abstractions are nothing but the “work” of machine-learning algorithms trained on the art canon online, dominated by the same Western art history introduced by the British settlers in Sri Lanka. The resulting image created by the algorithm were then painted on canvas by the artist’s studio, doubling the layers of mimetic interpretation. Next to them, Inkaaleneraam’s ceramics combine indigenous cosmology with intertwining bodies exploring sexuality beyond Western binaries, inspired by the Tamil Sangams, ancient poets and scholars.

The trite abstractions continue in an adjacent room where they serve as a frame for Being Human (2019/22), a second video installation by Kulendran Thomas created in collaboration with Annika Kuhlmann, like for the lower gallery’s piece The Finesse. As well as in the latter, Being Human combines conversations with real people around their lived experiences with CGI characters such as Taylor Swift covering a similar role to the above-mentioned Kim Kardashian, together with invented guests of the Colombo Art Biennale, part of what resulted from the market boom of art institutions during the post-war period. The (never seen) politically engaged version of Taylor Swift speaks out on the neoliberal duty of authenticity and filter bubbles in the American public sphere. “Everybody demands authenticity, and every artist believes they’re for real,” to the point that, she continues, “simulating simulated behaviour is the only way we have of being for real.” Besides, among the real people telling their real experiences of the aftermath of the defeated revolution, there is an appearance of Kulendran Thomas’ uncle, who once established the Center for Human Rights of Tamil Eelam.

On this account, in Being Human, the characters unfold a conversation between the politics of contemporary art and the logic behind human rights actions; Kant’s idea that our perception of reality is ultimately and merely built on the human mind’s laws serves as their glue. Humans are at the center, and reality lies in their interpretation. What is then the origin of “contemporary” in what we call contemporary art? An art that is “so liberated that its only foundational premise is that there is none” the characters claim. An art where artists can bring together, in a context of theoretical equality, “history, trash, language, and displacement”—nonetheless, “this space of theoretical equality is actually mediated by unequal powers.” Similarly, this happens with the international law that justifies human rights institutions and interventions. Referring to what happened (and didn’t) in the context of the Sri Lankan government war against Tamil Eelam, they argue on how then geopolitical issues are treated as human rights issues, and therefore dominant countries in the geopolitical axis are justified to solve it. “With no external arbiter,” the argument continues, “this legal space of theoretical equality is mediated by unequal powers,” mostly looking for their interests and thus reinforcing imperial power structures.

Besides the exhibition, since November 2022, the ICA is hosting Earth, a research community conceived by Kulendran Thomas that aims at developing “shared tools for new ways of living” in collaboration with KW Berlin. The research underpinning Earth is inspired by the Tamil legacy and particularly by their use of new technologies to manage a parallel economic system and to nurture a network among the digital diasporic communities of Tamils. Drawing on Tamil’s multidisciplinary understanding of pulavars, as described by Manmahal in the footage projected by The Finesse, the research project undertaken by Earth merges collaborations across art, architecture, and technology. Interestingly, the utopian community gathers in a dedicated space at the ICA just in between the lower and the upper gallery, demonstrating a physical dialogue with the works displayed and, in particular, with the various narrations of the characters that populate them. Following the project’s horizontal ethics, the researchers self-direct the work thus conducting a parallel experiment in coordinating production.

After January, the community project Earth originated from the ICA/KW Berlin exhibition will continue at earth.net. There is not much on the website yet, but it’s enough to get an idea of the project’s direction. Half of the homepage is dedicated to a set of pictures in rotation, whose content ranges from empty provincial landscapes to an overbuilt urban setting, all disturbingly enigmatic. The other half is occupied by an equally ambiguous/cryptic sequence of sentences, starting with: “You already know the story” and ending with: “But be honest with yourself: What do you really want? To stop time? To rewind it and play your part again, and perhaps get it right this time? To start over in the old world—a world that no longer exists? Or take your chances and build it anew? Do you feel ready?” In between, they speak of machine learning, neural engineering, gene editing, and renewable energy as tools to access an age beyond scarcity. An age where nation-states are outdone by networks, the East rises while the West perishes, cities are built beyond geography, and what else? “The age after money but before God.” Who knows. “If you’re into building cooperative economies” we read last on earth.net, “send us a message.”