Subverting the Archive

Through the story of how a little pagan hunter became a Catholic priest

George Senga’s exhibition at the Museo delle Civiltà in Rome closes the circle of his long research conducted through a work on a family archive that has brought out a reflection on the colonial past between Africa and Europe.

Curated by Lucrezia Cippitelli, Georges Senga. Comment un petit chasseur païen devient Prêtre Catholique is a site-specific exhibition that presents, for the first time and in a unified display, the photographic–film works and archive materials researched, produced and post-produced by Congolese artist Georges Senga on the figure of Bonaventure Salumu. The exhibition–which, after an initial informal presentation at The Recovery Plan in Florence [1] is also being hosted by the seventh Lubumbashi Biennale [2] currently underway, and in 2023, will be presented at WIELS (Brussels) and Framer Framed (Amsterdam)–is just one part of Senga’s project, which in addition to conducting research, has also produced an artist’s book.

Senga’s solo exhibition is part of the reopening of the Museo delle Civiltà, under the new direction of Andrea Viliani. Viliani has initiated new paths of research, archiving, cataloguing, communication, and dissemination of knowledge in an accessible and ethical manner: the museum’s new program questions the very nature of the ethnographic museum, its history and its collections, but above all the meaning that these collections have, and how they relate to the city in which they are located.

In its realization of this project, the Museo delle Civiltà faces a challenge: how can one ethically curate a collection that was born out of theft, violence, and to boast the exploits of a country?

But who was Bonaventure Salumu and why did Georges Senga make him the subject of a long process of investigation?

Bonaventure Salumu was a pagan hunter who, between the 1940s and the 1960s, was ordained to the priesthood as a Jesuit after receiving a Christian edition from some missionaries. Salumu lived between Europe and Africa during the decades of the Belgian occupation of Congo and, after traveling the world as a priest, returned to his home village–where he became a father and husband. Here he lived a secular life marked by the turmoil triggered by independence movements, civil wars, and decolonization from European empires.

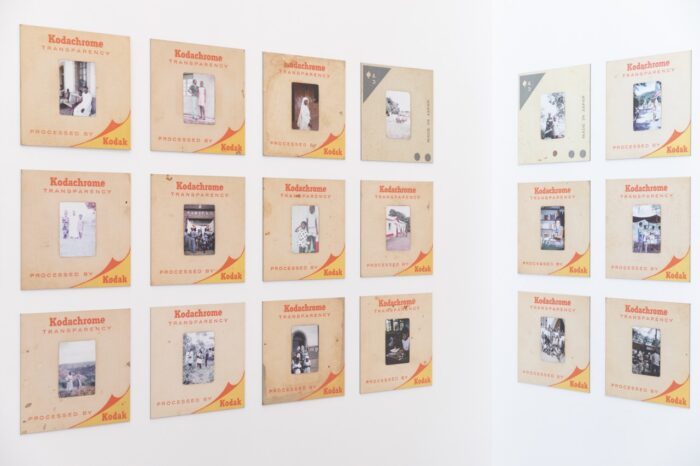

Senga came to Salumu’s life quite by chance after an unexpected meeting with his daughter, Marie-Thérèse Mukemwendo Bode Salumu. After this coincidence, Senga was able to explore the family’s private archives in Kiupshi, on the outskirts of Lubumbashi. Starting with the discovery of Salumu’s images, Senga undertook research that connected the family archive of the pagan hunter and the archives of the Jesuits and the Pères Blancs / Missionaries of Africa in Rome–which he had the opportunity to visit during his residence at Villa Medici.

“The photographs of many people, landscapes, and buildings in Belgium and Scotland compel us to see the world from the viewpoint and in the light of the experience of a Black Jesuit who visited many different cultures in a world in which tourism had not yet been Invented”. [3]

Through the narration of an intimate and personal story, Senga’s project explores pre-colonial and post-colonial relations between Europe and Africa, from the 16th century to what is defined as modernity. Senga develops his photographic work around history and stories that unravel and reveal themselves, shedding light on past and present. Memory and the search for connections in history and between people’s stories are the pillars on which his work is based. This also shows how this project came about. The artist writes:

“The title of this project refers to an image I found at an acquaintance’s house in Lubumbashi, my hometown, in the summer of 2017. The image was a reproduction of a local newspaper published in Congo, in which an article with this title recounted the biography of a Jesuit Catholic priest who left Congo in the 1950s to become a priest in Rome. Along with the picture, I found some personal photos of the priest taken during several trips to Europe and the Mediterranean, and a collection of kinescopes of Belgian landscapes. This discovery left me greatly surprised: the acquaintance, who later became a close friend, was the priest’s daughter. Knowing that Jesuits take vows of poverty, chastity and obedience, I immediately felt curious to know more about the life of this person, a family man previously, Bonaventure Salumu, who moved from a province in Congo, became a Jesuit, travelled through many countries during his life, and later returned to Lubumbashi.”

Reversing the Logic of the Archive as a Place of Power

Through his research, Senga was able to reveal a broader story, primarily involving colonialism. By interweaving private histories and public events, Senga’s excavation unveils the history of the Kongo Kingdom, the Belgian Congo and Zaire from a global point of view, covering a portion of the world that, since pre-modern times, was connected to Europe for commercial reasons–which is why the two countries can be said to have had a horizontal relationship.

Senga combines religion and secularity: on the one hand, the Catholicism of the religious congregations that marked Salumu’s life during the decades of the Belgian colony and the evangelization that linked Africa and Europe; and on the other, the family life of father and husband. Moreover, through his practice, he rethinks and questions the relationship between power, knowledge and its very production and distribution. He shakes up what has always been the production of white, male, Western, and heterosexual knowledge.

Senga opens a Pandora’s box and, in doing so, causes fractures. Fractures that let light filter through, allowing intimate and collective memories to emerge, red threads that bind people, what oral history and what objects, both resilient, leave behind–and in front of–them. Senga acts resiliently toward the archive as a form of power.

As Achille Mbembe impeccably explains in The Power of the Archive and its Limits (2002), the archive is the result of a selection made by a small group–hence an elite–of people, who judge what is appropriate to keep/remember and what is appropriate to discard/forget. The archive, as Mbembe writes, is nothing but status. The archive is a site of power and, consequently, as Jacques Derrida argues, of violence.

As Derrida argues in Archive Fever (1995), the archive is a reflection and, at the same time, a source of stat power. In this sense, it is extremely selective when deciding what gets in. What is accepted, preserved, transmitted conforms to the ideas of power in force. Therefore, only the voices of those who conform to that idea are accepted. The others are silenced and forgotten. Those marginalized by the state are marginalized by the archive.

The Congolese artists Georges Senga and Sammy Baloji start from the margin, giving space to what the archive has excluded. Margin, in this sense, is understood in the same way that Bell Hooks understood the margin, namely as something that is anything but a limit, but a possibility; a space of collective despair where resistance through creativity and imagination takes place.

These practices start from what is marginal because they starts from the history of an individual, investigating an archive that is anything but institutional or authoritarian. It starts from the margin as bell hooks would interject it, because it is and becomes a possibility.

“Marginality as site of resistance. Enter that space. Let us meet there. Enter that space. We greet you as liberators. Spaces can be real and imagined. Spaces can tell stories and un fold histories. Spaces can be interrupted, appropriated, and trans formed through artistic and literary practice.”

Baloji, like Senga, uses the archive to create photographic and video projects. As Gabriella Nugent explains in Colonial Legagies. Contemporary Lens-Based Art and the Democratic Republic of Congo (2021), photography and video are media that can be manipulated in every possible way. And there is a definite relationship between these mediums and time in the context of postcolonial Africa. As Nugent explains, they enable the temporal entanglements that characterize the construct of the postcolony theorized by Achille Mbembe. Postcolony, according to Mbembe, has a given trajectory–that of African societies emerging from the experience of colonialism with its concomitant violence. Of the most important concepts of post colony is the construction of time, which is made up of discontinuities, inertias, swings that are interconnected, that overlay one another. Through archive work and the choice of mediums such as photography and video, Baloji analyzes his country’s colonial past in order to reimagine Africa’s past, present, and future. Baloji uses the archival material to tell stories that displace official versions of the past and present, contesting old and cliched assumptions.

It is a practice of resistance and self-determination, aiming for an honest narrative. The artist, as Marina Garces would say, does everything to act honestly, which means putting oneself before power, stepping out of one’s comfort zone and subverting the world and the way one perceives it, as well as inhabits it.

How is this violence found? The so-called “archival violation” is found in the employment of documents with the aim of naturalizing and strengthening the power of the state, thereby silencing those who have no rights. Those who have no rights, also have no access to the archive. I venture to say that those who archive have power over life and death, if we conceive of memory as something organic, able to breathe and survive time. There is immortality in it. Those who archive exercize, sometimes, necropolitics–again, to return to Mbembe–thus the power that sovereignties have to have control over the death of individuals. [4]

The archive, as a reflection of and the source of state power, is extremely selective when deciding what gets in. Only those voices that conform to the ideals of those in power are allowed into the archive; those that do not conform are silenced. Those marginalized by the state are marginalized by the archive.

The artist’s book

The flagship of Senga’s research is the artist’s book. Published by Kunstverein Publishing (Milan), it brings together texts commissioned from three young writers from Lubumbashi. Their contributions are based on the collection of photographs presented in the book and are organized in three conceptual frames structured by the artists: Bonaventura’s youth and upbringing, his travels and family life in Zaire. Each text offers specific glimpses of a moment in Salumu’s life, elaborating on interviews, documentation and knowledge of history. It is a journey between reality and fiction, history and History. Kabuya’s aim is to help our imagination expand and immerse ourselves in the story of a man who left the country as Bonaventure, returned to Katanga as Abbé Salumu, vicar of Albertville (present-day Kalemie, a town on the western shore of Lake Tanganyika) and then decided to live a secular life.

The first chapter, entitled “White Fathers, Mother Earth and Black sons,” was written by Alexandre Mulongo Finkelstein (1984). He holds a degree in Industrial Electronic Engineering and has become a writer, rapper, screenwriter, and journalist. He is a founding member of Picha (an art center founded in 2008 in Lubumbashi by a collective of artists and initiator of the Lubumbashi Biennial) and has produced albums, films and a very popular blog offering new perspectives on Lubumbashi.

The second chapter, entitled “Long Walk,” was written by Ramcy Kabuya, a teacher, journalist, and writer with a PhD in Francophone literary history, currently living in Paris. His work deals with questions of aesthetics and intermediality. The author of numerous publications and a regular contributor to the journal Africultures, his texts are neither documentaries nor narratives: they are exercises in speculative writing, based on evidence and research.

Finally, the third chapter, entitled “Salumu,” was written by Bibiche Tankama N’Sel (1981)–who started writing under the pseudonym Bibatanko after her higher studies in Industrial Electronics. She is the author of poems, short stories and plays that have won several awards in Congo and abroad.

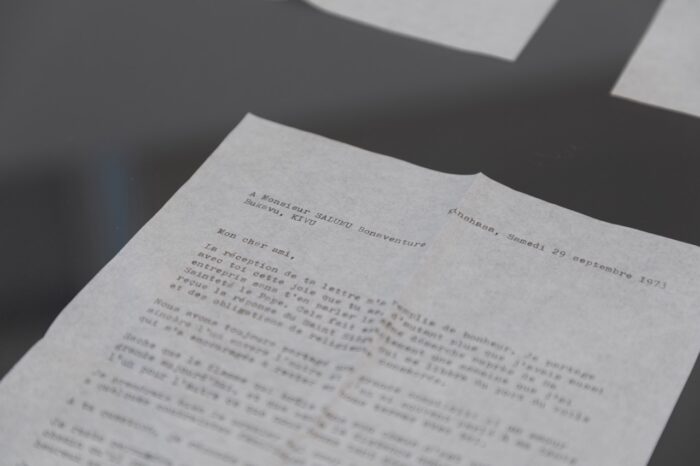

The book also contains fictional correspondence from 1971-1973 between Bonaventure Salumu and Sister Bode Lucie: a series of tender and profound love letters. Written by Bibiche Tankama and realized with an Olivetti Lettera 23, the love letters are fiction, undeclared, invented as plausible elements of a story rewritten by speculative fiction. The love letters are part of the exhibition at the Museo delle Civiltà as artworks.

A Small Reflection on the Role of the Museum Today

We must remember that coloniality is always present. According to the Peruvian sociologist Aníbal Quijano, “coloniality is still the most general form of domination in the world today, once colonialism as an explicit political order was destroyed. It doesn’t exhaust, obviously, the conditions nor the modes of exploitation and domination between peoples.” Although formal colonization is over, power dynamics related to race and gender continue to reign supreme. These oppressive hierarchies, despite the desire to achieve social justice, also pervade the realm of culture. This is why it is important for cultural centers to act ethically, which implies being responsible for what is presented and how it is narrated.

Ethics, on this level, serves to avoid pornomiseries and spectacles of pain–as is often the case with exhibitions of questionable scientific validity that thematize issues such as coloniality. As Emmanuel Lévinas wrote, on the other hand, “there is no ethical sense outside of responsibility towards others, nor can there be any ethics that is not a response to the demand of the other.”

I believe this dialogue is only possible through care and vulnerability. One must make space, be polyvocal, anti-tokenistic. One must pass the microphone, not thematize.

Cultural institutions must not be places of presentism, but must give us access to a polyvocal history, questioning the past and the present, for an honest future.

[1] Black History Month Florence is an initiative dedicated to celebrating Blackness and Black history. Its work focuses on artistic and academic creation, curation, and promotion in Florence, across Italy, and someday, throughout Europe. Every February, the month recognized internationally as Black History Month, BHMF puts together a digital program showcasing different exhibitions and events centered on African and African Diasporic culture and history.

[2] The Lubumbashi Biennale, founded in 2008 under the name of “Rencontres Picha,” is one of the most dynamic artistic events in Africa.

[3] Georges Senga, How a Little Pagan Hunter Becomes a Catholic Priest (Milan: Kunstverein Publishing, 2022): 117.

[4] According to Michel Foucault, sovereignty holds power over an individual’s biological life. This assumption is taken up by Achille Mbembe to define the ways in which sovereignty exercizes control over the death of individuals (a concept referred to as necropolitics and which considers the issue of race to be prominent in the calculations of biopolitics).