Readymade Writing

Kenneth Goldsmith on plagiarism, citation, publishing, archive fever and printing out the internet

Poet, writer, artist and founder of UbuWeb, the leading online archive of visual and sound poetry, Kenneth Goldsmith has been plotting a true insurrection in the world of culture for over twenty years, convinced that for the first time in history, language is capable of altering the media as we know them, thus producing a definitive break with tradition. According to a study cited in Uncreative Writing: Managing Language in the Digital Age (Columbia University Press, 2011; Italian translation by Valerio Mannucci, Ctrl+C, Ctrl+V: Scrittura non-creativa, NERO 2019), the average person in the United States consumes 100,000 words a day. “Faced with an unprecedented quantity of digital text,” Goldsmith observes, “writing needs to redefine itself so that it can adapt to a new environment marked by textual abundance.”

The digital text thus becomes the double of the printed one, a ghost in the machine. In the era of the Internet, words create dependency, they accumulate infinitely, undifferentiated, broken into bits to reappear in new constellations of language that produce amnesia. Someone who writes moves within a recyclable, reusable, retrievable ecosystem: rather than the myth of creation, Goldsmith honors, adores and exploits manipulation and reuse, plagiarism and citation. For this hyper-modernist poet, letters are “identical building blocks: none of them is more important than the others.” Words are temporarily organized codes on textual documents in the form of constellations; otherwise they can become videos or turn into images: to then, perhaps, become text once more.

Vincenzo Santarcangelo: You studied sculpture at college. It seems, however, that you have no interest in shaping language: “We don’t need the new sentence, the old sentence re-framed is good enough” is one of your mottos. Do you think any trace of those years of apprenticeship has remained in your work, in some way?

Kenneth Goldsmith: When we shift linguistic contexts from one place to another, we shape them, hence Marcel Duchamp’s reassignment of found objects; if Duchamp could do that with sculpture and John Cage could do that with sound, then I thought that I could do it with language. While we tend to emphasize the semantic qualities of language, certain strains of modernism taught us to value their formal qualities as well, the audio and visual aspects of language. In the digital age, language can literally be picked up and moved via cut-and-paste, making it extremely physical. It can also be displaced à la Duchamp (think of how you share, say, an Instagram photo, providing recontextualization each time it is viewed); in this way, we can say that the entire Internet is one big Duchampian readymade.

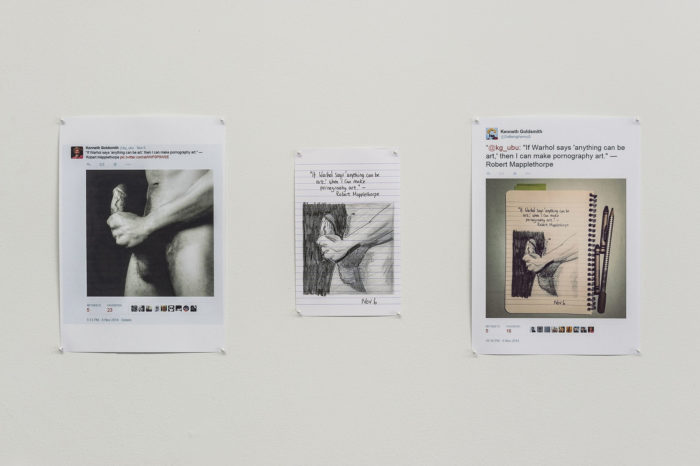

Kenneth Goldsmith and Fox Irving, 5:13 PM – 6 Nov 2014 (Mapplethorpe), 2014. One and three twits, 2015. Courtesy Freddy gallery, Baltimore.

For much of the Eighties and early Nineties you worked hard at carving out a reputation as a text artist—you were into hip-hop and words that rhymed. Have you ever been part of the hip-hop scene and what do you think of contemporary rappers’ vocabulary?

I think that the most exciting linguistic and poetic experiments have been taking place in hip-hop, now for nearly four decades. The formal brilliance and innovation has pushed the limits of language as far as James Joyce or Gertrude Stein did, but in a completely different direction, one that balances the semantic and formal qualities of language, in ways that echo the concerns of modernism. But it’s even better because unlike modernism, hip-hop is popular in ways that modernism was repellant to most people.

Did you have an “Imaginary Museum of Works and Artists” of your own or were you busy killing your idols, then?

I never wanted to kill my idols. I love them. UbuWeb is a twenty-five-year paean to my idols. All of my books have paid tribute to them. For example, in Capital: New York Capital of the Twentieth Century, I rewrote Walter Benjamin’s Arcades Project for New York City in the twentieth century. I adopted his exact methodology to do so; in the end, the book was the identical size as his, consisting of half-a-million words. Likewise, in my book Seven American Deaths and Disasters, I transposed Andy Warhol’s use of death imagery in painting into language, and so forth. I see the digital age as being an extension of modernist concerns. If we could see our current century as a continuum rather than a radical break, we might not feel so threatened by it.

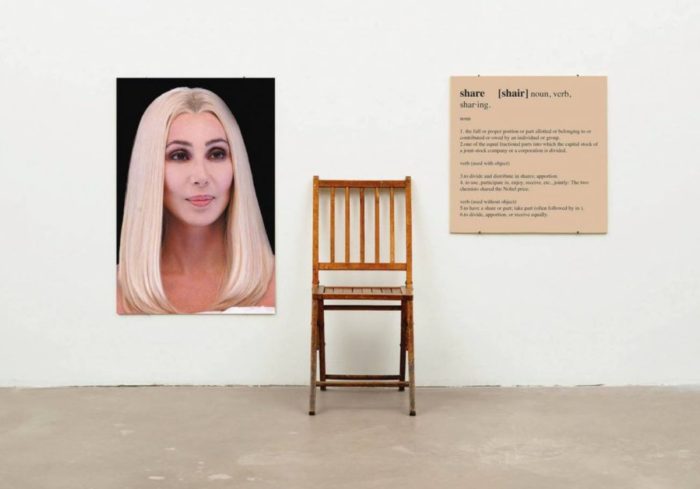

Kenneth Goldsmith’s twitter, One and Three Chers #postconceptualism. 1:32 AM · May 12, 2017.

Your struggle against the myth of creativity is long lasting. “Creativity,” you wrote, “is the thing to flee from, not only as a member of the ‘creative class’ but also as a member of the ‘artistic class.’” Why? Technology is playing a crucial role in this respect. How?

I love creativity so much, which is why I set out to destroy what it has become. To me, creativity is no longer creative; it has become formulaic. A friend of mine did a formal analysis of the finalists for The Man Booker Prize a few years ago. What he discovered was that all the books were templates of one another, each with similar narrative arcs, sweeps, and resolutions. Their uses of language were also nearly identical. He discovered that the books were lacking in creativity and innovation, more resembling paint-by-numbers than original works. All of these books aspired to be made into Hollywood films, one no different than the other. Yet these are hailed as the most “creative” literary works of our time, when in reality there’s little creative about them. I thought that perhaps in order to reinvigorate creativity, we needed to adopt an inverse idea of originality, admitting all the things that were never permitted: copying, plagiarism, falsification, repurposing, etc. Suddenly if we accept these ideas into our practices, we can have a new notion of creativity, one that is more honest in the twenty-first century when all we do is copy-and-paste in an infinitely replicative environment.

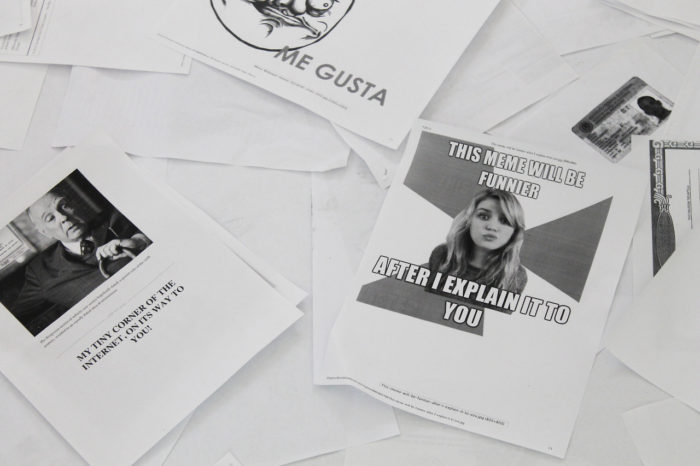

Kenneth Goldsmith, Printing Out The Internet, LABOR Mexico City, 2013.

In one of your Uncreative Writing classes, your students were rewarded for plagiarism, identity theft, repurposing papers, patch-writing, sampling, plundering, and stealing. Moreover, they were told that they had to have their laptops open and connected in class. “And so,” you write, “we have a glimpse into the future.” Why?

Let’s decriminalize plagiarism. Instead of it being a practice that is done surreptitiously, what happens if we accept it as another tool in our writing toolbox? What happens if we use it responsibly and sensibly out in the open instead of recklessly and criminally in secret? We’ll find that what we choose is as expressive of ourselves as the things that we write “originally.” Choice is authorship. No matter how hard we try, we can’t escape our taste, biography, and subjectivity. I think as writers we try too hard to express ourselves, whereas everything we do is expressive of ourselves.

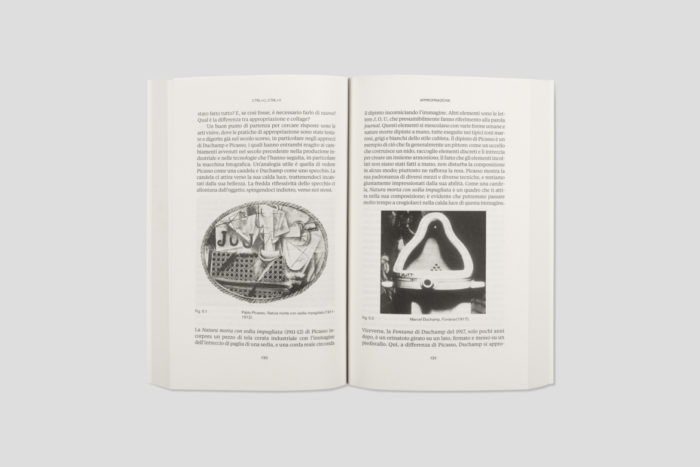

Ctrl+C, Ctrl+V: Scrittura non-creativa, NERO 2019.

What, in your opinion, is the future of the traditional printed book and the publishing industry?

Ten years ago, we heard that the web was going to kill books, but that turned out not to be true. Now there are more books than ever and they’re more beautiful than ever. I think people got tired of shitty PDFs. I think people got tired of piles of pixels. I go into a bookstore today and everything is unbelievably designed, printed on thick paper, and bound in the most luscious covers. Today, even philosophy books have been repackaged to be beautiful. I’m thinking of a recent series of the selected works of Walter Benjamin, which are rainbow-colored books with grainy, romantic black-and-white photos from the period on the cover— images of stainless steel fans, old-fashioned cameras, and wet city streets shot at night. The content is of course the same. But because of the web, the packaging is over the top. And the weird thing is, that in spite of their good design, Benjamin doesn’t mean anything less than he did when he was swathed in ugly covers. Good design didn’t hurt him one bit. You wonder why this didn’t happen long ago? Because the worst designed thing in the whole world—the web—made good design possible. Paradoxically, the web has given us back the artifact. So instead of asking what the web can do, it might be better to ask what it can’t do. The web cannot produce a beautiful book. The web cannot produce a thick piece of vinyl. The web cannot produce a delicious locavore meal. The web cannot produce a glazed piece of ceramics. The web cannot produce a soft woven sweater. And the web cannot produce a unique oil painting—which makes all of these things more valuable than they were before the web.

Your book Wasting Time on the Internet (Harper Perennial, 2016) is based on a class you taught at the University of Pennsylvania, whose syllabus declared: “Distraction, multi-tasking and aimless drifting is mandatory.” What did you learn from a pedagogical point of view from that experience, and why did you decide to make it into a book?

When we waste time on the Internet, we always do it alone—in a coffee shop, in the library, in a bedroom—and it’s a lonely and often sad experience. Yet if we waste time on the Internet in a room with a group of people together in meatspace, we find that suddenly it becomes connected, engaged, and hypersocial. Our bodies and minds become extensions of the machine (in a McLuhanesque sense) and we begin sharing emotion and ideas in completely new ways. For my class, all we did was sit together in a room and surf the web communally for three hours a week. It was hyperemotional and hyperconnected. It was magical, more akin to a yoga studio or think tank than what we normally consider wasting time on the Internet. It was a way of reimagining and recapturing, in a Debordian sense, the notion of lost time, transforming it into unalienated celebration.

Hillary – The Hillary Clinton Emails (NERO, 2019)

Internet culture is surely suffering from an Archive fever due to an overload of speech texts and images, but it seems that you consider this a positive thing rather than a disease. You’ve said you are a “radical optimist” about the Internet and the “creative renaissance” that it can generate…

On the Internet, our problem is abundance. And abundance is a lovely problem to have. Today, the use of an artifact is in its management rather than in its traditional content. I spend much more time organizing and archiving my artifacts instead of listening to them or engaging with them. Like everyone else, I have more PDFs and EPUBs on my drives than I’ll ever be able to read, more AVIs and MP4s than I’ll ever be able to watch, and more MP3s than I’ll ever be able to listen to. And yet, each day, I keep acquiring more. While this is all in “the cloud,” I prefer to have an infinitely rich local archive, one that is always free and accessible, administrated and managed by me, rather than by big corporations. Use the cloud, but don’t trust it. If you can’t download it, it doesn’t exist.

Hillary Clinton at Kenneth Goldsmith “Hillary: The Hillary Clinton emails” curated by Francesco Urbano Ragazzi at Despar Teatro Italia, Venice. Photos © Gerda Studio

Hillary – The Hillary Clinton Emails (NERO, 2019) explores the boundaries between unveiling the mechanism of power and creating the plot of unjustified paranoia that generated reactionary consequences. How have the theories of conspiracy and suspicion, instruments of the counter-culture of the left, become weapons in the hands of the most dangerous right?

When an artifact is digital and immaterial, it is susceptible to any type of interpretation you wish to give it. And nobody can refute it because nobody has seen it. This is why I wanted to print out the Hillary Clinton emails—by giving them a physical presence, it was a rebuttal to Trump’s constant absurd query of “Where are the 30,000 emails.” I wanted to respond in an undeniably concrete way, “Here they are.” And this is the beauty of sculpture; its fact-ness, its physicality is undeniable in a newly desirable way at a time in which immateriality is subject to nefarious interpretations. What we’ve seen in the digital age is a very dark turn to Lucy Lippard’s famous idea of the “dematerialization of the object.” Instead, we need to re-embrace and reinvestigate concretist ideas from mid-century modernism, stemming from places as far flung as Brazil to the former Yugoslavia. Today, the fact of materiality is a way of debunking fake news.