Non-Human Witnesses of a Genocide

A conversation with Mark Mushiva on Forensis and Bill Kouligas’ “The Drum and the Bird“, a sonic and visual investigation into the German genocide in Namibia

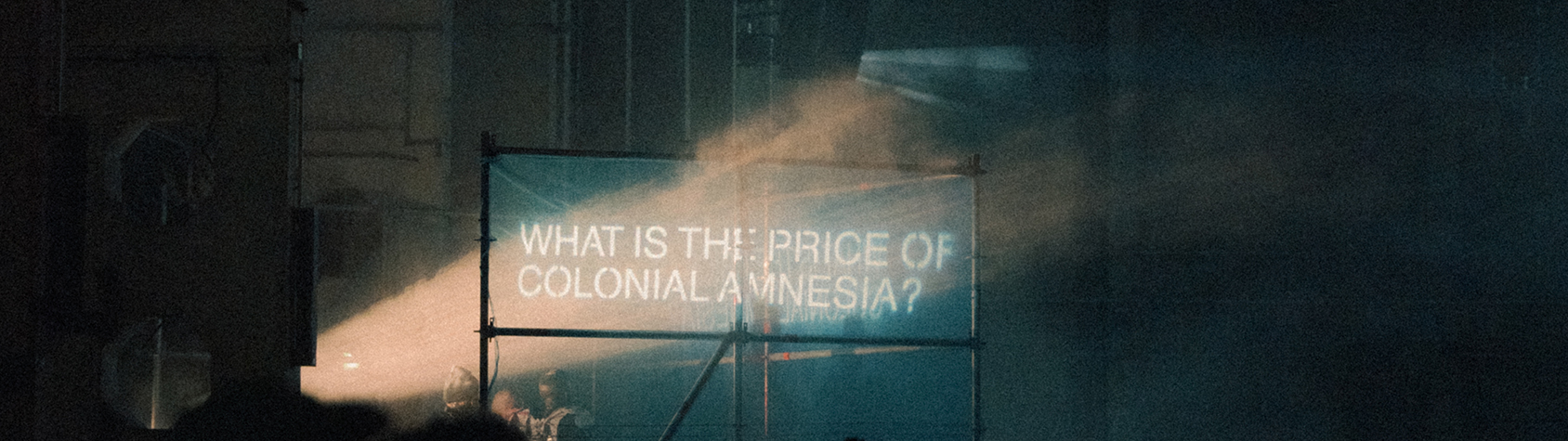

During the first of three days of Openless (Berlin Atonal) at the end of August 2024 in Berlin, the senses and consciousness of hundreds gathered in a monumental former GDR power plant, now Kraftwerk, were overwhelmed by testimonies of horrific torture and massacres, visual reconstructions of the crimes’ scenarios, and waves of deep bass sounds that resonated in everyone’s chest. The collaborative sonic and visual performance by Forensis and Bill Kouligas, titled The Drum and the Bird, uses generative environmental audio, oral testimonies, and spatio-visual modelling to recreate the forgotten genocide of the Herero and Nama peoples perpetrated by the German colonial army on Shark Island and in Hornkranz during the colonisation of Namibia. The descendants’ testimonies, Forensis’s reconstructions, and Bill Kouligas’s soundscape pervaded the concrete space with a dense sensory atmosphere, evoking in the audience a mix of dismay, horror, and rage, intensified by the realisation that the German state is once again supporting yet another genocide, this time against the Palestinian people.

Felice Moramarco: Non-human witnesses are central to The Drum and the Bird. Could you expand on how you identify these witnesses and the methods you use to examine their roles?

Mark Mushiva: Colonial violence, like other forms of violence, leaves traces, the destruction of human bodies and built environments is often the most legible, but we believe that landscapes and ecologies also bear these traces, which require a special attunement. It is our experience that conventional scientific methods often ignore traces of colonial violence left on non-human witnesses. For the purpose of our research, we consulted indigenous elders whose knowledge allowed us to find evidence held in the landscape, rocks and vegetation in a different way. Some of their testimony also spoke to the sheer violence of land dispossession by German settlers that laid the groundwork for the apartheid related inequalities that can be seen in Namibia today. It is through the guidance of our partners and the extended indigenous communities they belong to that we were able to identify evidence, and we used a combination of analysis, remote sensing, 3d reconstruction and interviews to develop insights from the research.

Despite being often considered an ephemeral form of information, sound plays a crucial role in this investigation. Could you explain how you deployed it?

Sound, particularly the elemental sound of the wind, is an important character in the memory of the genocide in Namibia. Descendants of the survivors and victims of the genocide have enshrined the wind in songs and oral stories about the genocide. In this way, it becomes a non-human agent through which we can understand the machinations of the colonial perpetrators who weaponised the coastal winds to exterminate the prisoners of the genocide, especially on the notorious Shark Island, where survivors of the genocide were worked to death between 1905 and 1907. The wind shaped the geological architecture of the camp, carried the colonisers to the shores of Namiba and is at the centre of a present-day green hydrogen scheme between the incumbent Namibian and German governments, who are attempting to greenwash the history of the genocide with dubious social development goals. It was important for us that all these elements become legible in our performance, which threads the sonic character of wind with other musical elements to present the results of our research and narrate the centrality of the wind as a witness and co-investigator.

Talking about the role of sound, The Drum and the Bird is the result of a collaboration between Forensis and Bill Kouligas, merging forensic analysis with dub theory. How did you bring these distinct methodologies together to reconstruct scenarios from the German genocide in Namibia?

When you look at the central tenets of dub theory, they are about orchestrating a way of storytelling that emphasises absences, certain elements of a song fall away to highlight parts of the composition. In the same way, our research also interrogates absences such as the lack of visible signs of mass graves or transformed landscapes, which we are sure are there but need forensic methods to elaborate on those absences. Our choice to lean on dub theory came after the investigations, when we were looking at different compositional styles in black culture that could inform our audio performance for Atonal 2024.

As you mentioned, both Forensis’ investigative methodology and dub theory engage with the absence or gaps within the narrative of historical events. How does working within these gaps shape the narrative of The Drum and the Bird?

The first part of the Drum and the Bird lays out what is essentially a demonstration of the sonic dispossession currently being carried out by the Namibia and German government as they facilitate the implementation of a green hydrogen scheme that will not only displace and destroy flora and fauna, some of which are thousand year old plants, but also the disturbance of unmarked graves which are all over the desert at the town of Lüderitz. By layering sounds of industrial development and field recordings of the non-human entities at Lüderitz, we sought to emphasise how these two forms of futures are currently competing to exist, with the sounds of memory of the genocide and the future of various non-human life quickly being drowned out by the metallic sound of progress. This serves to illustrate the silencing of various cultural and environmentally important actors whose voices are being encroached upon by a violent and continuing colonial history that creates absences with erasure. In the second part of the performance, we use the metaphor of wind generated algorithmically to narrate an 80-year history of colonial environmental change using calculations done on available satellite images that show that Namibia’s grasslands are quickly transforming into a desert because of persisting colonial agricultural practices. Although these changes solidified under apartheid South African rule that started in the 1920s until 1990, they were architected by German colonial officers, missionaries, engineers, and settler farmers.

Forensis and Forensic Architecture have shown how powerful visual reconstructions can be in exposing violence. But recent events—like the live-streamed genocide in Gaza—make it clear that just showing images is not enough to stop these crimes. In your view, what role can images really play in driving political change? And how can they move beyond documentation to become active tools of resistance?

The genocide in Gaza has definitely forced many of us to question the role of documentation, perhaps even beyond that, it is forcing us to question our collective values. I do not believe that it is possible to stop the ongoing crimes and human rights abuses without confronting the very calculus that defines who is human and who belongs to some other less deserving category. Between the two genocides, the current Palestinian genocide and the Nama and Herero genocide, there is a gross disavowal of the value of human life that continues to perpetuate violence and death. Maybe I can only humbly say that the evidence we create has been produced at the request of our partners who are laying claims for justice every day on the ground, and I believe much of the work is to support those claims. In Namibia, our investigation has halted the continuation of tourism on sites of genocide and has attracted the special attention of the United Nations and other human rights groups. It takes time to see true transformative change, and perhaps we are nearing the point where movements of resistance will reach the critical mass required to bring needed change. We can only hope that adding our voice and work to these movements brings that change a bit faster.