Minii Ger

Safe and Sound #1: Natalia Papaeva

Minii Ger by Natalia Papaeva is a part of the program Safe and Sound, curated by the duo League of Tenders as part of the Nomadic Program 2024–2025 of Vleeshal Center for Contemporary Art (Middelburg, the Netherlands), and first published by Nero.

Safe and Sound draws on a performance by American artist Jana Haimson, held at Vleeshal almost 45 years ago, in December 1979. In this improvised piece, Haimson combined vocalization with experimental choreography. Haimson is among the western artists who explored and developed various genres of time-based art, often using scores as starting points for performative improvisation.

To reflect the concept of the score, as well as the production and transmission of knowledge in non-western cultures, League of Tenders invited three artists of different origins, living across Europe—Natalia Papaeva, Mukaddas Mijit and Yaniya Mikhalina—to create their scores and propose someone to perform them.

These scores are addressed to and inspired by their communities, offering a means to unite people across borders, within diasporas, and far from their homelands. Performing these scores—through their bodies, voices, and spoken words in their native languages—becomes an act of shaping their communities as visibly present, seen, and “sound.”

In her project Minii Ger, Natalia Papaeva explores the feeling of home and the sense of belonging among fellow Buryats living, like herself, in the Netherlands. Drawing on their thoughts and memories, she composed a song performed by the same participants. By carefully curating the setting for the performance, Natalia aims to create a space for the community to reflect, practise their rituals and reconnect to their language. Despite being performed far from their homeland, these traditions find their embodiment and continuation in their shared experience.

This series includes projects by Mukaddas Mijit and Yaniya Mikhalina.

Natalia Papaeva — performance idea and art direction

Mirella Moschella — videographer

Luo Changli — sound assistant

Rijksakademie — film studio

Participants:

Tatiana Visser

Ayuna Khantaeva

Altana Mikhakhanova

Maxim Cheremnykh

Shipieva Natalia

Evgeny

We live in the Netherlands, but all of us are from Buryatia. We don’t gather often, but when we do, we always talk about home. We cook buuz, sometimes boov (Buryat-Mongolian dishes), and drink milk tea. In December, people start talking about Sagaalgan—the Buryat-Mongolian New Year according to the lunar calendar. Is anyone getting together? When we are meeting? Where, whose place?

Sagaalgan is a family holiday. For a whole month, family and friends visit each other. Before Sagaalgan begins, the days are filled with preparations: mantras are recited, houses are cleaned, thoughts are purified, and prayer wheels spin in the datsans.

In a new home, in a new country, Sagaalgan can feel like a lonely holiday. Late in the evening after work, you eat buuz alone. All the other rituals fall away, and you can’t decide: should you wake up early on the first day of the young moon, like people do at home, or not? Should you meet with others and explain the holiday customs, or is it better to just gather with compatriots?

Should you go home for Sagaalgan in winter? Or maybe in summer?

Three years ago, I celebrated Sagaalgan on Lake Baikal for the first time with colleagues and friends, not with family. During Sagaalgan, it’s customary to greet guests with a special welcome ritual where two people extend their hands, and the younger support the hands of the elder. This is a regular ritual in our family.

At Baikal, among friends, I realized this ritual wasn’t that familiar to everyone. We fumbled, asking each other, “How do you do it correctly?” Buryatia is vast; in some areas, traditions are better preserved, while in others, they’ve nearly faded away.

When we first gathered to discuss the project, I hadn’t anticipated that we’d choose this greeting as the basis. It has become a unifying link for people from various regions of Buryatia, Zabaykalsky Krai, the Irkutsk region, Mongolia, and the Buryat-Mongolian diaspora.

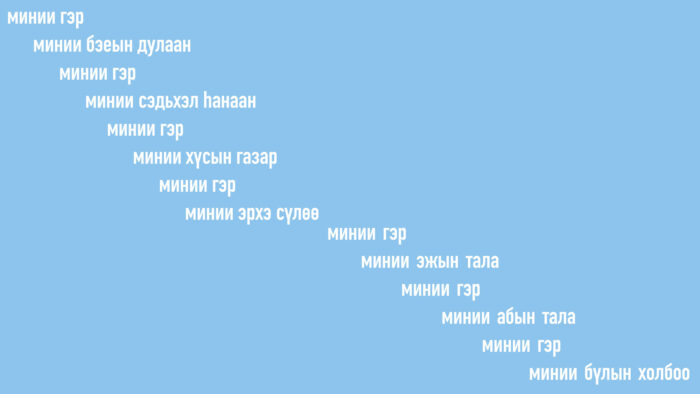

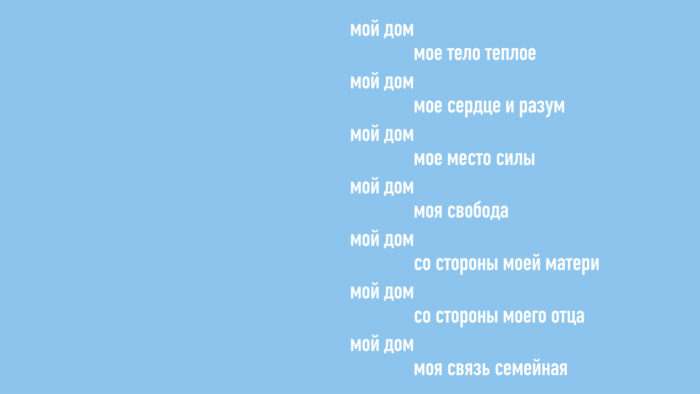

Another cornerstone of the project is a song. To write it, I sent questions about “home” to everyone, and based on their responses, I shaped the lyrics and melody. The melody came as a memory of songs that I and other participants heard in childhood—at lush weddings, celebrations, and in songs of our mothers and grandmothers. It doesn’t refer to any specific song but echoes many other Buryat long songs.

Singing is a common practice, both at large gatherings and at home. It doesn’t have to be professional or require a beautiful voice and perfect pitch. Singing is a way of expressing oneself, a way to convey one’s emotions and feelings. The people who participated in the project aren’t professional singers either, but their voices are important for highlighting different accents, tones, and styles of performance styles. Some don’t speak or are just learning the Buryat language. Some speak its various dialects. Many of us don’t use Buryat in daily life.

The song in this project also exists separately from their voices—as a soundtrack performed by a professional opera singer. He is also from Buryatia but now lives in Germany.

When you move to another country, you change forever. You build a new home and become part of another society. But you don’t leave your home behind completely; you always carry its foundation within you. People who have also lived in your country, your republic, are witnesses and co-participants in these rituals and traditions. And so, we will meet again in February for Sagaalgan, make buuz again, drink milk tea, and then will return to our Dutch homes.