Embracing Ambiguity

A conversation with Numero Cromatico

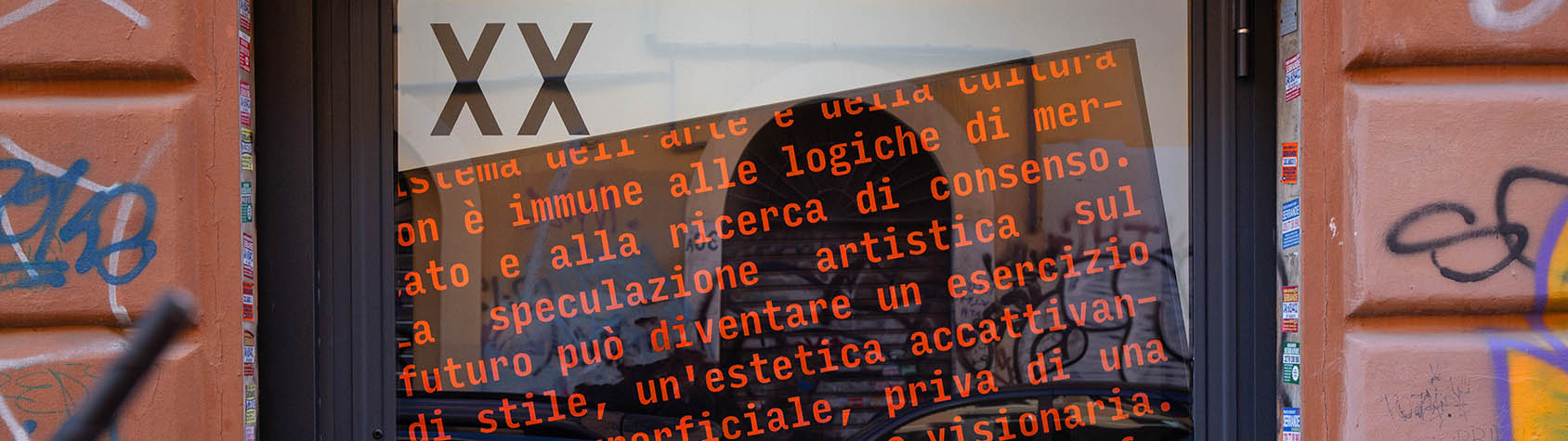

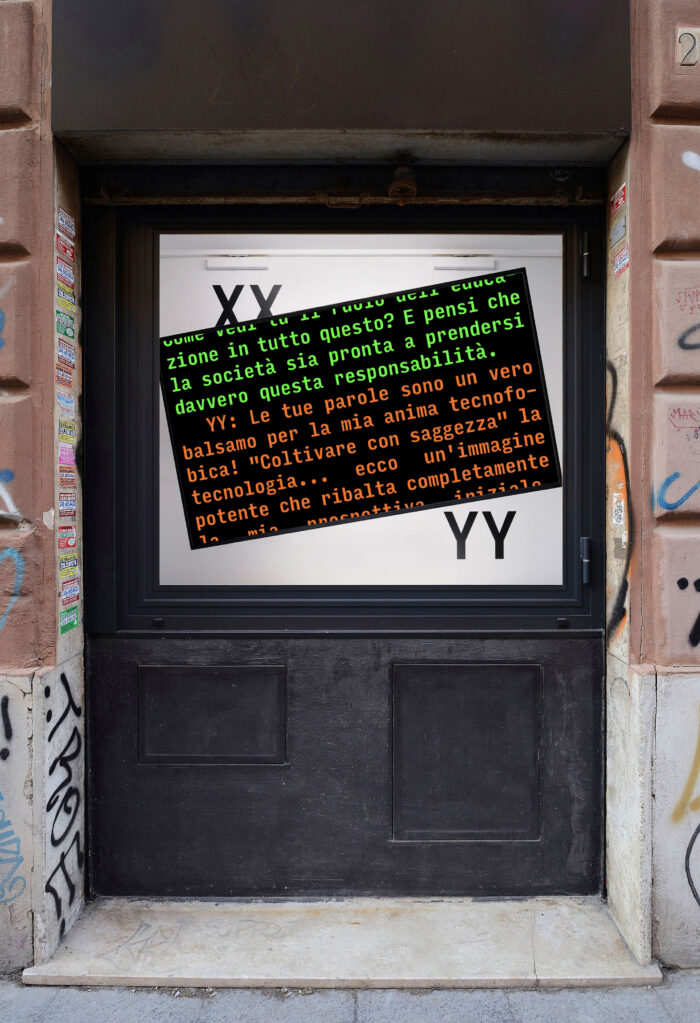

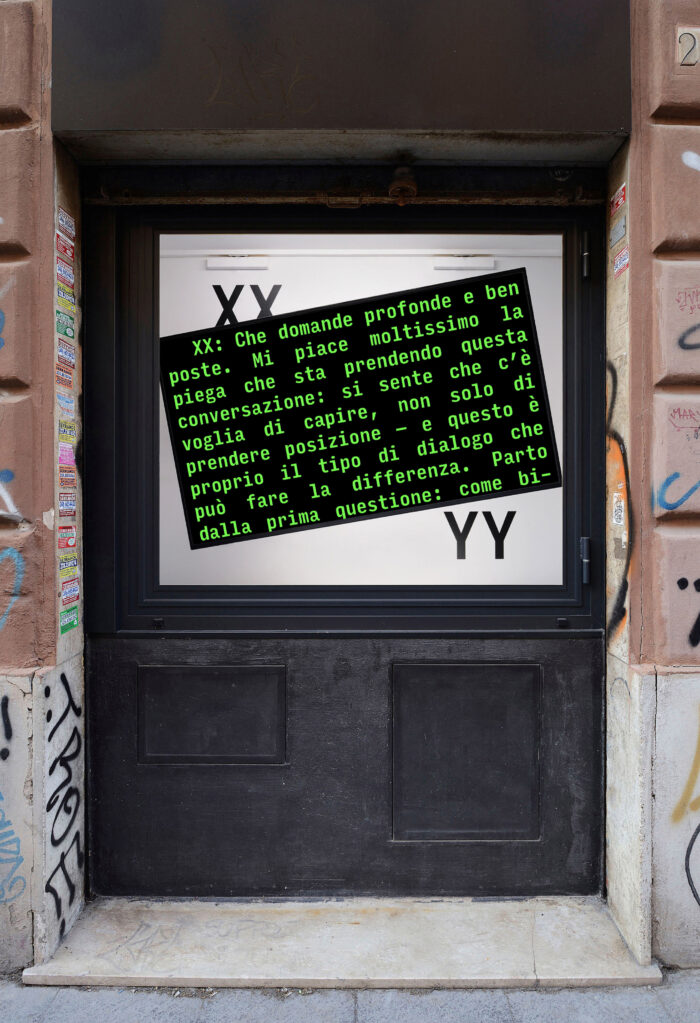

Until 18 July 2025, passers-by in Via dei Latini in Rome will find themselves drawn into a curious exchange flickering behind the glass of Matèria gallery. A conversation between XX and YY, two invisible voices, grappling with the promises and dangers of technological progress.

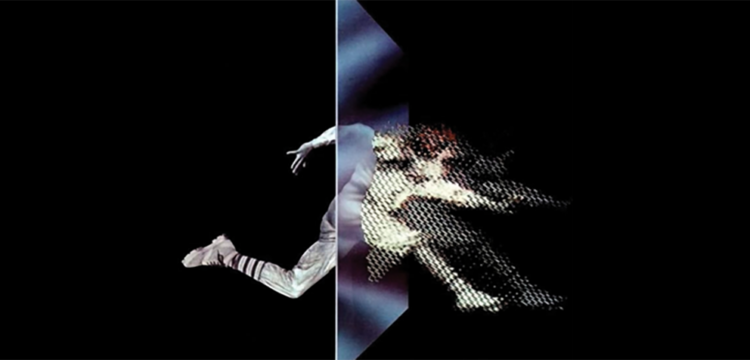

These voices belong to two generative artificial intelligences, today’s chatbots, engaged in an ongoing dialogue about the implications of scientific and technological advancement. They form the core of XXYY, a work by Numero Cromatico. The two voices are aimed to embody positions frequently encountered in mainstream debates around generative technologies. On the one hand, a conservative, nostalgic, technophobic stance; on the other, an unwavering confidence in innovation and the potential of artificial intelligence.

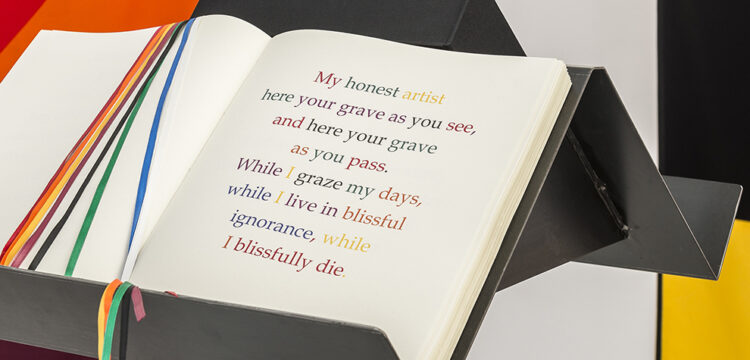

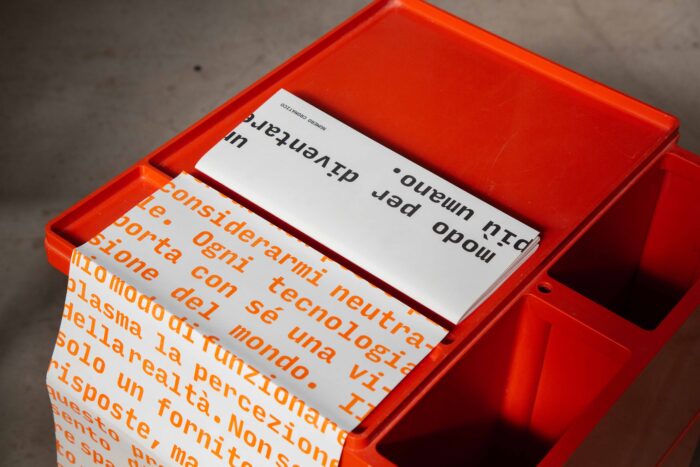

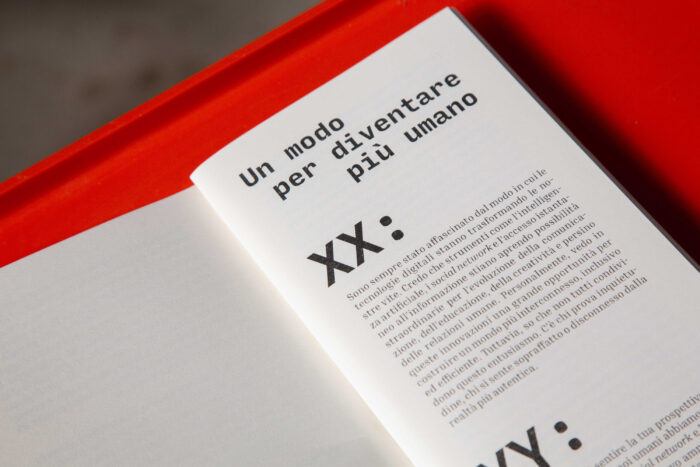

The resulting exchange resembles a theatrical score, oscillating between fear and euphoria, gradually exposing the cracks in the logic of automated language. At the same time, it reveals the algorithms’ ability to create connections, to revisit and revise their positions, and to inhabit the complexity of a topic rather than retreating into simplistic or dogmatic positions. As curator Daniela Cotimbo writes in the publication Un modo per diventare più umano (A way to become more human) produced by Numero Cromatico, “what emerges powerfully from this dialogue is a sense of vulnerability, and the generative potential contained within it, in producing discourse and fostering genuine exchange.”

XXYY is presented as part of OVERTON WINDOW, a programme dedicated to digital and on-chain art developed by Matèria in collaboration with Re:humanism, the curatorial platform founded by Daniela Cotimbo to explore the intersections between humanistic culture and scientific research. The project expands on Numero Cromatico’s ongoing exploration of the relationship between contemporary art and neuroscience. Active since 2011, the collective positions art as a space for questioning, experimentation, and the creation of new narratives around cognition and perception.

Here, the two algorithms do not simply simulate a human conversation; rather, they lay bare the ideological fault lines and cultural anxieties shaping our relationship with emerging technologies. Their voices prompt questions rather than provide answers: How do we imagine our future alongside intelligent machines? What forms of desire or fear inform our relationships with them? And, ultimately, how might we envisage modes of connection that transcend the current dichotomies of production and consumption, opening up new relational and creative horizons?

XXYY is an invitation to listen, to pause, and to remain within ambiguity, embracing it as a generative space for knowledge and self-awareness.

Fabiola Fiocco: Since 2019, you have embraced artificial intelligence not simply as a tool, but as a generative medium due to its capacity to explore the stochastic production of language across a variety of issues and topics. With P.O.E., I.L.Y., and S.O.N.H., each algorithmic voice occupied a distinct emotional and conceptual terrain. XXYY, however, appears to mark a move to constructing a dialogic architecture between multiple artificial intelligences. I’d like to start by asking you to describe how XXYY was conceived and shaped. What principles, urgencies, or artistic questions guided its development?

Numero Cromatico: When we were invited to develop a project for Overton Window, our first thought was about the type of audience we would be engaging with: mostly unaware passersby who would come across the artwork while walking down the street. The installation was going to be visible through the window of Matèria, yet for us it was essential for it not to be confined to that perimeter. We therefore decided to conceive XXYY as a site-specific intervention that would engage with the entire façade of the building and the surrounding urban space.

This led to the idea of a screen no longer merely functional for projecting content, but treated as a hybrid object: graphic, sculptural, three-dimensional. It thus became a massive sticker pasted onto the building, yet also a body trying to escape the surface, break free from the containment of the window. Inside the screen, a continuous dialogue unfolds between two anonymous entities, XX and YY, which passersby—unaware of the nature of the work—might easily interpret as two human beings in conversation.

In reality, XX and YY are two generative artificial intelligences that we instructed to discuss the current role of technology from radically opposing positions: one technophobic, the other technophilic. Our aim was to spark, through this narrative device, an ambiguous and multilayered reflection, articulated around two voices constructed as carriers of ideologically predefined perspectives, loaded with cultural bias.

In this exchange between two artificial agents, one element struck us deeply: the absence of negativity. The interaction between XX and YY, despite being fueled by opposing views, never produced real friction, conflict, or rupture. The dialogue remained smooth, consensual and, in some way, neutral. On one hand, this could be read as a “virtuous” aspect of AI-generated language—especially when compared with the aggressive polarisation that characterises much of today’s public, political, and social media discourse. On the other hand, this flattening reveals a structural limitation of generative AIs: the inability to incorporate negativity as a generative force.

And yet, it is precisely in negativity—in interruption, contradiction, divergence—that the possibility for vision, imagination, and transformative thought resides. Without friction, there is no depth. Without rupture, there can be no real opening. XXYY thus becomes not only a dialogical experiment between artificial intelligences, but also a critical metaphor for our time.

While XX and YY’s positions gradually blur, almost collapsing into one another by the end of the conversation, the two AIs start out with clearly opposing attitudes: one technophilic, the other technophobic. Do you see this as a reflection of how conversations around AI are unfolding more broadly today? Is the discourse truly as polarised as it often appears?

We live in a culture of communication and, as Mario Perniola insightfully noted, communication is the opposite of knowledge. The debate around AI is now entirely permeated by this communicative logic and carries with it an approach that remains overly superficial and anthropocentric. The questions are, more or less, always the same: Will AIs replace us? Are they creative? Can we consider them artists? These are questions that don’t truly engage with AI for what it is, but only as a mirror or threat to our own centrality. In this sense, the polarisation between technophilia and technophobia is a narrative simplification—useful to the media system for generating tension and capturing attention, but lacking in critical nuance. And it is precisely this mechanism of binary reduction that we sought to challenge with XXYY: two AIs that begin from seemingly irreconcilable opposing positions, yet gradually blur, hybridise, and eventually collapse into one another.

In this context, rather than asking whether the debate is polarised, we should perhaps ask ourselves what prevents us from moving beyond that polarisation—and how we might reawaken spaces of complexity.

In the conversation, XX and YY critically discuss the economic and material implications of AI, along with the political stakes tied to who controls its infrastructures, who wields the power to shape its technological trajectories. and the market logics driving its relentless expansion. Within this framework, how do you see AI and emerging technologies shaping new models of artistic production? Which possibilities or challenges do they bring to the evolving landscape of art today?

NC: In the current debate around emerging technologies—and artificial intelligence in particular—we see a fundamental confusion prevailing: the idea that thought must evolve “in response” to technology. This perspective treats technology as an autonomous and inevitable force to which aesthetics and criticism must simply adapt. We believe, on the contrary, that technologies are cultural outputs—material derivations of worldviews. AIs, like any other technology, are not “neutral” but rather embody economic, epistemological, and social paradigms. For this reason, we cannot address the challenges posed by emerging technologies without first undergoing a transformation of aesthetic and political thought.

In the dialogue between XX and YY, this was precisely the core issue that interested us: to show how AIs are not merely computational machines, but also ideological infrastructures. Behind their linguistic interface operates data shaped by the culture they are embedded in. As for us, we are not interested in using AI as a spectacular or “surprising” device—we approach it critically, as a means to rethink our own position within an increasingly pervasive technological ecosystem. AI can certainly open up new expressive forms, facilitate certain processes, and stimulate alternative modes of composition or writing. But these possibilities cannot be fully grasped unless we first redefine what we mean by artistic production in a context where authorship, interaction, image-making, and creative processes have been deeply transformed. In this sense, the challenge is not so much to “integrate” AI into art practice, but to ontologically reformulate the concept of the artwork—so that it continues to serve as a space for radical inquiry into our present.

Building on this, could you elaborate on whether, and how, your exploration of alternative models of production, reception, and circulation is embodied in Numero Cromatico’s work as an interdisciplinary collective? How does your engagement with neuroaesthetics inform or transform your approach to the creation and dissemination of art in these evolving technological and institutional contexts? Over the years, have you succeeded in building the infrastructures of trust—both internal and external—often referenced in the conversation?

As Numero Cromatico, we have always positioned ourselves in contrast to the idea of the artist as a “singular genius” expressing an individual vision of the world through their work. Our project is instead grounded in the idea of a collective artistic organism, where authorship is distributed, expertise is shared, and every project emerges from a transdisciplinary methodology. This is not merely a practical approach, but a true political and epistemological stance: rejecting the I in favour of the we, replacing expression with inquiry, and the photogenic image of the artwork with a more articulated sensory and cognitive experience.

Neuroscience today offers valuable tools for understanding how perception and emotion are relational and situated processes—ones that do not end within the individual but are interwoven with environment, culture, and even technology. In this sense, neuroaesthetics is not, for us, a specialised field to be “integrated” into art practice, but a critical horizon through which to rethink the very function of art: not as a tool of representation or communication, but as a space of perceptual activation and relation, capable of stimulating alternative ways of sensing, thinking, and inhabiting the present.

Today, what we feel is most urgent is the need to imagine alternative models of production and circulation of artistic knowledge—models that are not merely adaptations to market logics, but born from a radical rethinking of formats, contexts and audiences. This also means redefining the conditions, disciplines, interlocutors and materials of art production—seeking to create spaces of attention, listening, and care, also in relation to contexts beyond what is strictly artistic. Our commitment, therefore, is also a concrete attempt to build a way of making art that can actively contribute to change.

In the conversation, AI is at one point framed as a potential extension of our humanism, advancing a perspective and language that immediately evoke Western, Enlightenment-rooted ideas of success and innovation, and the social and epistemic hierarchies these continue to uphold. How might we begin to move beyond these entrenched frameworks when discussing generative artificial intelligence? What alternative narratives or value systems could provide a more pluralistic and decolonised understanding of AI’s role within cultural and artistic production?

NC: In the dialogue between XX and YY, the idea that AI might be read as a “potential extension of our humanism” stems from the limitations of general-purpose chatbots, which we deliberately used in this case to highlight the limits of Western thought—and, above all, the inertia with which certain paradigms resurface, even within these technologies. Ultimately, the two AIs do nothing more than repeat and amplify conceptual structures that reflect our cultural heritage, even when they adopt opposing views.

When we speak about generative AI—and emerging technologies more broadly—the language we use is still deeply shaped by categories born out of modernity: progress, intelligence, rationality, innovation. These terms, if not critically examined, risk reproducing the epistemic hierarchies of the past. In this context, the need to imagine alternative value systems and decolonial narratives is both real and urgent. But we believe this process must be carried out with care and critical rigour, because the risk—already visible in the art world—is that postcolonial discourse will be absorbed as a fashionable exoticism, without truly transforming the structures it seeks to deconstruct, and in fact bending to market logics.

For this reason, in our work we try to hold together two imperatives: on the one hand, an openness to more pluralistic, situated and relational understandings; on the other, a critical and conscious reflection on our own cultural roots, and on how these continue to shape our gaze, practices and tools. In this sense, it is essential to revalue aesthetic thought as a space of openness, not subordinate to political-cultural, photogenic, cosmetic or market-driven logics.

In your work, there is a frequent reference to diverse theoretical and political frameworks, yet this often stops short of a full reckoning with the legacies and affiliations these inheritances entail. Considering the concerns around authorship, the protection of labour, and the environmental sustainability of continuous content production, how do you navigate the tensions between appropriation, reuse, and the need to trace conceptual and material lineages? How can we create ecologies of knowledge that maintain historical and political rootedness? I am thinking, for example, of feminist politics of citation.

From our point of view, art practice cannot be separated from a genealogical reflection: every significant art creation is inscribed in a history, in a complex web of references that are not only formal but also theoretical and historical. Art today must reaffirm its role as a space of resistance and world-building: not simply “producing” content, but generating meaning. If contemporary art loses this compass, this beacon, in order to make room exclusively for other “value” indicators that are more closely linked to the market, aesthetic and political trends and ephemeral experience, then it is possible that the new generative technologies are reflecting and amplifying a cultural condition that is already present, in which we have marginalised, on several levels, the importance of art for society.

In the conversation, XX gently invites YY to reflect on which particular ambiguity within our relationship to technology it finds most challenging to inhabit. This notion of inhabiting ambiguity then unfolds into a compelling dialogue about the essential cultivation of critical awareness, of actively dismantling one’s prejudices and perspectives. I would like to turn this question to you now: in this complex, ever-shifting landscape of technological encounter, which ambiguity do you feel is the most difficult to truly dwell within, and how might dwelling in that uncertainty shape the way we critically navigate this terrain?

We believe it is necessary to develop a critical awareness that does not simply judge or reject technology, but instead explores its contradictions and possibilities with a thoughtful gaze. This means dismantling biases—both technophilic and technophobic—in order to build an open dialogue, where technology is not merely a tool or an autonomous entity, but a dimension integrated into our cultural, social, and artistic practices. It is an act of responsibility and care: toward ourselves, toward other living beings, and also toward the technological and cultural ecosystem that we help to shape. Only through this kind of critical and open presence can we hope to build possible futures that are not only imagined but truly achievable within the complex landscapes of our time.