Constructing Identities

In a political and spiritual exile: the solo show by cypriot artist Theodoulos Polyviou at Fondazione Elpis in Milan

From 10 April to 7 July 2024, Fondazione Elpis presents Un Palazzo in esilio (A Palace in exile), solo show by Theodoulos Polyviou, third chapter of Transmundane Economies, an ongoing project that the artist began in 2022, utilizing virtual reality and related digital technology to study, reconstruct and restore gaps within Cyprus’ cultural heritage. By means of videos, sculptures, installations and drawings exhibited in all the Foundation’s spaces, the exhibition begins from the project for a Cypriot archbishopric building, at the center of a historical episode that actually occurred.

A black cat wanders around the bright parquet on the first floor of Fondazione Elpis in Milan. After climbing the white wall, the cat walks along its top plane surface. The scene plays on a video in the middle of the room, making it difficult to say whether it’s a recording of a real event or a fictional one. Did the cat actually walk there? Is the black cat even real? The image of the black cat alternates with those of an enigmatic architecture, where grey visions of natural elements and skies open up towards a possible way out. Cypriot artist Theodoulos Polyviou (b. 1989, Nicosia) navigates the non-space at the boundary between reality and virtuality. He employs symbols of exclusion and marginalization to challenge mainstream institutional narratives and historical ideologies rooted in the past and memory of his homeland, Cyprus.

Un Palazzo in esilio (A Palace in exile) is the third chapter of Transmundane economies, an ongoing project started in 2022 that, in the artist’s words, “deploys virtuality and associated digital technologies to study, reconstruct and fill voids in Cypriot cultural heritage”. More specifically, this chapter reimagines historical events associated with the activities and power of the clergy in Cyprus. The architecture depicted in the video is Polyviou’s reimagining of the new Archbishop’s Palace in Nicosia, which serves as the residence and administrative headquarters for the Church of Cyprus. The palace was constructed in the late 1950s, a crucial moment in defining the island’s identity as Cyprus was in the process of transitioning from British colonial rule to Independence. Utilizing a wide range of media, the artist analyzes the intrinsic architectural and symbolic qualities of the palace to shed light on the impact of the overlapping religious and political authority in Cyprus during the mid-20th century.

Un Palazzo in esilio (A Palace in exile) opens with a site-specific installation of molds. They are original pieces from the artist’s archive and they were used for the construction of churches and ecclesiastical buildings across the island, including the Archbishop’s Palace in Nicosia. This marks a significant return to sculpture in Polyviou’s practice. The objects are manipulated by the artist, who applies a golden paint reminiscent of the Byzantine icon tradition, and they are displayed in an architectural landscape that occupies the entire ground floor of Fondazione Elpis. The history of the palace dates back to 1950, when the newly elected Archbishop Makarios III launched the region’s first-ever competition for the design of a new office and residence. The construction, partially concluded by 1959 at the dawn of Cyprus independence, mirrors the expanding influence of Makarios in both political and religious affairs of the island. As Sia Anagnostopoulou describes it, the period marks “the first phase of his ethnarchic career”, during which he developed first as anti-colonial and pro-enosis leader and then, accepting to cooperate with the British administration in a transitory constitution of self-government, as president of a post-colonial republic.

During those troubled years, nationalism in Cyprus was gaining ground and the idea of enosis, the annexation of the island to Greece, was becoming a radical movement with various ideological and political implications. At the same time, the concept of ethnarchy, which embodies the Church of Cyprus’ attempt to be the only national and political voice of the people, was leading to a convergence of the spiritual and political spheres. This ethno-religious leadership of the nation came together with Makarios’ election as first President of the newly established Republic of Cyprus in 1960, just a few months after his return from exile, which lasted from 1956 to 1959. The construction of the palace continued largely in Makarios’ absence. When he triumphantly returned to Cyprus, the building was still unfinished, prompting a rapid acceleration of the work to complete it. Polyviou humorously speculates about the last-minute solutions that might have been implemented for the liturgical and functional operations of the building. Temporary Paschal Stand, a sculptural work exhibited on the lower level of Fondazione Elpis, is a candle holder made of tubular metal trunks holding ecclesiastical candle votives, sourced from a workshop right across the palace. The blend of liturgical and industrial elements evokes the ambiance of the night when Makarios took up residence in the palace. In the adjacent room, a series of collages is on display. These collages feature screen-printed advertisements from local and British newspapers, often incorporating a hybrid language of Greek and English. Among them is an advert for cement, likely imported from the UK. Alongside Σαρκά, a broom hand-crafted from dried bundles of native Cypriot spiny shrubs historically used by municipal workers during British rule, the artworks highlight the deep roots of colonialism in Cyprus.

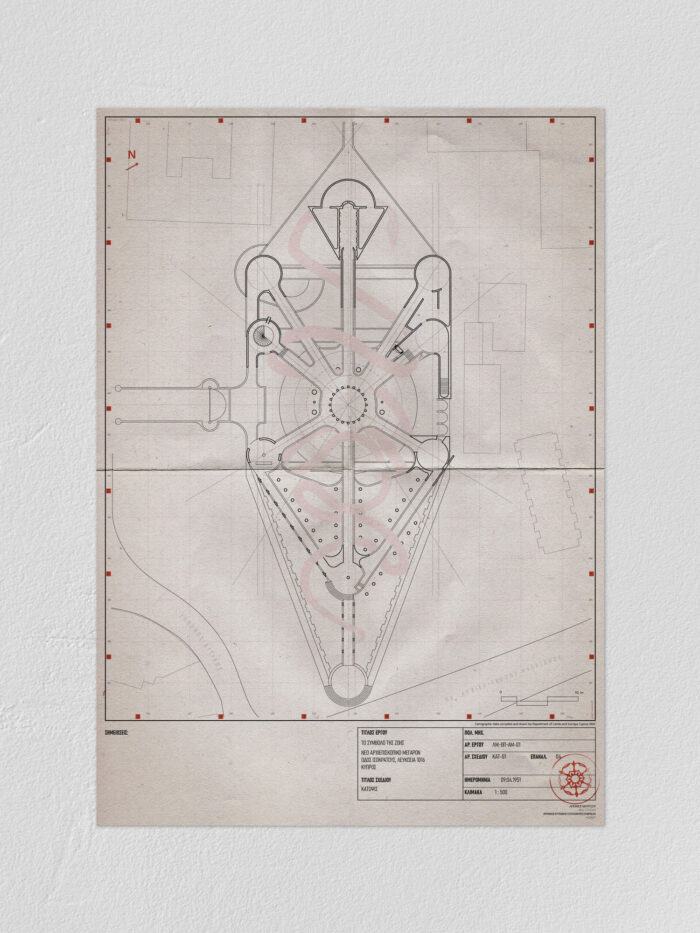

Polyviou imagines participating in the architectural competition launched by Makarios in 1950. The artist, in collaboration with architectural designer Loukis Menelaou, presents here his own proposal through various mediums: a CGI film walkthrough of the virtual reconstruction of the proposed archbishopric, screened on LED panels; a CNC-machined architectural maquette of the same building, crafted from wood repurposed from the ceiling of the Fondazione Elpis, combined with 3D-printed elements in rosy pink resin; a series of section drawings, rolled up and placed against the back corner of the room; and finally, an architectural floor plan. Polyviou offers a counter-narrative to the palace, characterized by an anti-monumental and subterranean style, drawing inspiration from the teachings of Daskalos (Stylianos Atteshlis, 1912-1995), a Cypriot mystic and healer. Daskalos was a key figure in introducing mysticism into the Christian discourse in Cyprus and, despite his growing appreciation within the Cypriot community, he was marginalized by the Church. Polyviou explores Daskalos’ work through texts and drawings, using his oeuvre and spiritual heritage to identify gaps in the narrative told by the Church of Cyprus. For example, the floor plan of the new building proposed by Polyviou and Menelaou is directly connected to his drawing Symbol of Life. This diagram transcends a mere architectural plan: through its centers and the paths between them, in fact, the symbol represents the entire process of creation and the journey to humanity’s origin.

A strong connection can be found between the Symbol of Life and the recently unearthed body of work by Swedish artist Hilma af Klint (1862-1944), entitled Tree of Knowledge (1912-15). According to Jadranka Ryle’s analysis, af Klint drawings were produced concurrently with a series of paintings intended for the never-realized Temple of Spiral Architecture, which bears a circular form similar to Polyviou’s architecture. Closely related to the Yggdrasill, the three-tiered tree that embodies the cosmos in Norse mythology and offering a solution for humanity, af Klint’s Tree of Knowledge also references the Garden of Eden, the starting point of consciousness in Christianity, as suggested by Bettina Kaufmann and Kathrin Shaeppi. During the 19th century, the symbol was co-opted into nationalist and nationhood politics. Af Klint subverts nationalist and patriarchal romanticism with her abstract, secret, diagrammatic aesthetic language challenging and redirecting the use of Yggdrasill towards the possibility of progressive gender relations.

Polyviou explores the experiences of minority and marginalized social groups by analyzing the impact that certain architectures, particularly ecclesiastic ones, have on the creation and reinforcement of ‘otherness’. With a specific focus on the queer community, the artist traces existing links between architecture and queerness, and how the process of exclusion has been exacerbated by religious-nationalist discourses. I see Polyviou’s re-imagining of the palace in Nicosia as an invitation for a more collective and inclusive view of Cypriot identity. Un Palazzo in esilio (A Palace in exile) is an artistic endeavor that de-idealize Cypriot cultural heritage from a queer perspective, acting as a “purification act” to separate political affairs from religious influences. Drawing from Daskalos’ teachings, Polyviou’s work infuses a mystic, spiritual, and intimate perspective into the exploration of these dynamics. His contribution to addressing marginalization, particularly through dismantling architectural barriers, is manifested in the construction of a non-space, tangible enough to be understood, yet evocative enough to challenge monolithic paradigms.

Alessandro Cazzola: The exhibition Un Palazzo in esilio (A Palace in exile) at Fondazione Elpis in Milan represents a significant return to sculpture in your artistic practice. Previously, your work seamlessly integrated CNC machining and 3D printing into immersive installations, where elements were experienced both virtually through VR and physically as objects in spaces. In this exhibition, you are presenting a new series of works as standalone sculptural pieces. What inspired you to revisit sculpture at this stage in your career, particularly for this exhibition? Why did you choose to work with molds, and could you discuss the process of manipulating and reworking them

Theodoulos Polyviou: The selection of molds is from my personal archive and marks the starting point of a year-long research behind the exhibition. Originally sourced from the now-defunct Koromias factory in Nicosia, these molds were used in the construction of not only the Archbishop’s Palace, but also several other churches across Cyprus. In the exhibition, the molds oscillate between their historical and archival status. I call them “dogmatic negatives”. They are literally church inverses, or “negatives”, allowing for an examination of the underlying structures that imbue their positive counterparts with meaning and significance. One of them is covered in gold, engaging with the symbolic and liturgical meaning of gilding in Christian Orthodox traditions.

The teachings of Daskalos plays a leading role in the definition of this project and in your personal reconfiguration of the Archbishop’s Palace of Nicosia, both architecturally and conceptually. Your personal connection to his spiritual activity emerges in the show on several levels. Who was Daskalos? Why do you feel so related to his spiritual practice and what specifically has influenced the conception and preparation of the show Un Palazzo in esilio (A Palace in exile)?

Daskalos was a Cypriot mystic and healer who emerged in the 1950s and spent most of his life in Strovolos, Nicosia, merely a stone’s throw from where I grew up. His books entered my life at a pivotal moment when I was particularly open to his teachings, even though I had never actively sought them out. In 1952, as his following expanded, the Church of Cyprus accused Daskalos of spiritualism fraud. Facing pressure, he was compelled to appear at the Archbishop’s palace and publicly renounce all ties to occultism and spiritualism, an act meant to demonstrate his repentance and adherence to the Church. There was a degree of suppression that I drew parallels with, relating to growing up queer in Cyprus. His visit to the palace becomes symbolic within the context of the exhibition, as it signals the possibility of a counter-narrative to the one the Church was advancing at the time.

In Fondazione Elpis, alongside your video work on the first floor, you are exhibiting a drawing that goes beyond a simple architectural floor plan. Its mystical, esoteric quality, evokes the influential work of early 20th-century artists, such as Hilma af Klint’s Tree of Knowledge series (1913-15). What does your Symbol of Life represent here, per se and in the wider context of Un Palazzo in esilio (A Palace in exile)?

Reflecting on the 1950s competition, I wondered what it would have been like to be alive at the time… I pictured myself as a follower of Daskalos, drawing heavily on his influences for my design. The Symbol of Life, central to his teachings, naturally became the cornerstone of the architectural plans and it posed an interesting question: what would it mean to propose such a building at the main headquarters of the Church? I considered the implications of introducing a structure inspired by his esoteric teachings right at the heart of the Church’s administrative center. Such a proposal would not only challenge the architectural norms of those times but also potentially disrupt the traditional religious ideologies of the palace itself. It would serve as a bold statement, integrating mystic symbolism into a space traditionally dominated by orthodox Christian doctrine. To my understanding, through the Symbol of Life, Daskalos introduced concepts from Kabbalah within the framework of Christian mysticism, specifically in Cyprus. The Symbol is not merely a diagram; it is considered to be energetically charged. It can be thought of on a bodily level, like an armor or as an architectural divine blueprint. Daskalos believed that if one is drawn to it, they might have already been interested in it in a previous life.

Your work frequently explores the politics of accessibility in spaces, particularly questioning how architectural structures, such as ecclesiastical and religious buildings, can inadvertently serve as tools for marginalization. This theme is evident in your current project, which extends to the social dynamics in Cyprus. You often highlight the experiences of marginalized groups, including the queer community. How do you examine the relationship between architecture and queerness in your work? Additionally, how do you bring this analysis to a spiritual level, as influenced by a healer like Daskalos?

The story of any place is one of constant change, where physical space transforms into historical space, and in becoming historical, turns virtual. Both queer and religious spaces trace this trajectory in similar and compelling ways. Central to my research is the Cypriot Orthodox Church’s profound influence on the political landscape of the island, which significantly shapes national collectivity. The Church often serves as a universal remedy for a ‘post’-colonial nation grappling with various challenges. Consequently, groups like the queer community experience marginalization through complex identity-formation processes, as scholar Nayia Kamenou mentions in her writings. Similarly, the Church’s architectural presence serves as an anchor for national identity and religious traditions, extending its influence far beyond its spiritual role. My work engages with such architectural semiotics to highlight, categorize, and challenge the structures that hold them, reflecting on the politics of accessibility they possess. I am interested in architecture defined not only by its physical form but also by the social voids that shape and contain it to provide insights into history, ancestry, and spirituality.

Un Palazzo in esilio (A Palace in exile) is the third chapter of your ongoing project Transmundane economies. Through the analysis of ecclesiastic buildings and architectural elements, you are conducting a re-signification of the cultural traditions and religious processes deeply rooted in Cypriot history. What does this new chapter add to the project and how does it bring Transmundane economies to a further step of evolution? You have informed me that Un Palazzo in esilio (A Palace in exile) will be the first of your projects to be shown more than once, in other institutional venues after its presentation in Milan. How do you intend to re-install and re-contextualize the exhibition?

Un Palazzo in esilio (A Palace in exile) set within the context of Transmundane Economies, examines the concept of oikonomia and its extension to the Church of Cyprus’s influence over both spiritual directives and the governance and stewardship of mundane material economic and political interests. As already discussed above, the project deals with the Church’s impact on wider societal issues, including nationalism and identity politics, and it offers a new perspective for contemplating notions of place, history, and cultural or collective identity. This coming September, the show will travel to Berlin and Düsseldorf as part of the Double Feature Program at The Julia Stoschek Foundation, curated by Lisa Long and Line Ajan. The site-specific film, which premiered at the Fondazione Elpis in Milan in 2023, will be adapted to the galleries of the Julia Stoschek Foundation, in Düsseldorf and Berlin, while all other works will be divided between the two spaces.

This chapter acts as a bridge to the next, which delves deeper into the teachings of Daskalos, aiming to transform his principal healing practices once constrained by the technological limitations of his era into a series of immersive experiences.

*Talk: “Trascendental Spaces and Immersive Architectures, exploring Transmundane Economies with Theodoulos Polyviou and Andrea Franchetto”, moderated by Sofia Schubert. The talk will take place at Fondazione Elpis in Milan, on July 4, 2024, at 6.30pm

*Show: Un Palazzo in esilio (A Palace in exile) is on view at Fondazione Elpis in Milan until July 7, 2024

REFERENCES

Sia Anagnostopoulou, Makarios III, 1950-77: Creating the Ethnarchic State, in A. Varnava and M. N. Michael (eds.), The Archbishops of Cyprus in the Modern Age: The Changing Role of the Archbishop-Ethnarch, their Identities and Politics, Cambridge 2013, pp. 240-292.

Bettina Kaufmann and Kathrin Schaeppi, “Illuminating Parallels in the Life and Art of Hilma af Klint and C. G. Jung”, in ARAS – The Archive for Research in Archetypal Symbolism, issue 4, 2019, pp. 1-44.

Jadranka Ryle, “Reinventing the Yggdrasil: Hilma af Klint and Political Aesthetics”, in Nordic Journal of Art & Research, 7(1), 2018.