A Difficult Heritage

Visions from the Family Archive. Vernacular photography as a mean of self and collective analysis

On January 7th, 2024, following a tradition that marks every year since 1978, a collective gathering took place in Rome to commemorate the deaths of Franco Bigonzetti, Francesco Ciavatta, and Stefano Recchioni. The three young men, approximately twenty years old, were activists of the Fronte della Gioventù, the youth organization of the Movimento Sociale Italiano – Destra Nazionale (Social Italian Movement – National Right), a neo-fascist political party. They were killed by a communist terrorist organization during the tumultuous Years of Lead, and the perpetrators have never been identified.

For 46 years, in front of the former headquarters of the Movimento Sociale Italiano (MSI) between Via Evandro and Via Acca Larenzia in the Tuscolano district, hundreds of people, men and women, gathered to remember the three losses in a ritual rich of symbols of Italy’s historical past. The institutional meeting took place in the morning in Via Acca Larenzia, where the massacre occurred, and where a commemorative plaque for the neo-fascist youths is affixed. The President of the Lazio Region and the Culture Councillor of the Municipality of Rome were present. The assembly concluded with laying two laurel wreaths at the location that gave its name to the event.

Later, at 6 p.m., Via Evandro 8 filled with a procession of people forming parallel lines, arranging themselves in a military formation in the open space that once housed the original party headquarters. The surrounding streets already hinted at the nature of the place and the commemoration that was about to happen. Analyzing the symbols in the area can help to introduce a topic that will be explored in the text through an artistic lens: the fascist past of the country and the difficult heritage of memories it preserves.

The walls of the buildings were covered with posters dedicated to Carlo Giannotta, an activist of the Movimento Sociale Italiano in Tor Pignattara, who passed away in 2019 of natural causes. He is considered a central figure in the memory of Acca Larenzia and the caretaker of the premises of the former MSI headquarters in the Tuscolana area. His black-and-white image is distinguished by his political beliefs, explicit through the Celtic cross symbol—a silhouette unequivocally associated with fascist ideology—and the inscription “Acca Larenzia”, emphasizing the dual connection to that location and its history.

Besides appearing in occasional murals, the Celtic cross characterized a series of black posters, more numerous this time, featuring the profile of an eagle and the coordinates of the appointment “January 7 at 6 p.m.,” with the rallying cry “Present”. The perimeter of the square in front of Via Evandro 8 is visibly marked by the same black circle divided into four sections by two lines. Indeed, a simple search on Google Maps reveals the satellite image of a Celtic cross, creating a constant interplay of correspondences between symbols and places. Italian flags and fasces surround the square’s boundary. The former entrance of the MSI headquarters is accompanied by two comic-style murals depicting, on the left, a gladiator with a banner reading “acca larenzia” and the customary Celtic cross, and on the right, a man in barbarian attire wielding the fasces’ axe, striking a triumphant conquering pose, standing on the ruins with open arms.

As announced on the posters, later that evening, hundreds of people poured into the neighborhood. Their gaze was directed towards the former party’s venue that has, perhaps, never been so relevant. An unknown commander, among the black banners bearing the inscription “Honor to fallen comrades”, thundered a “For all fallen comrades…” awaiting a response that was not long in coming. A resounding and sharp “Present” vibrated through the air, letting the sound of those assertive words propagate throughout the neighborhood. The Roman salute accompanied the military shout, transforming those lines of people into a veritable fascist squadron. The voice of the unknown commander raised two more times, repeating the exact phrase. The crowd’s voice erupted two more times, always giving the same response, and producing the same gesture. At the announcement of “Comrades at ease”, the lines scattered, leaving visible the large Celtic cross painted on the ground.

The fascist liturgy that has been described so far, and which radically detached itself from a commemorative event, found its perfect setting in a place so full of references and allegories. A well-suited place to host moments of historical revisionism, which emerged with all their problematic aspects. Imagine now that what happened in Rome is replicated in all the places across the country that have preserved symbols of the regime and that allow for other collective gatherings with an apologetic purpose.

What would be our image of the country? What is our relationship, today, with the places that preserve distinct signs of Italy’s fascist memory? Do we have any possibility to interact with them without revitalizing the political reasons for which they were built? Can we attempt, in some way, to approach this difficult heritage and decolonize it?

These are some of the questions that have led to the realization of A Difficult Heritage: Visions from the Family Archive, a personal exhibition by Laura Fiorio in collaboration with Mario Margani and curated by Ginevra Ludovici and Giulia Menegale at the Remont Gallery in Belgrade. The exhibition focused on the reflection of the problematic legacy left by the fascist past, which, in this case, was expressed through the personal archives of the two Italian artists. Fiorio and Margani have primarily worked on photographic documents depicting their grandparents during colonial occupations in Africa in the 1930s, specifically in Ethiopia and Eritrea, allowing their family memories to interact. Beyond their visual collaboration, the artists’ relationship took on a written form. On the occasion of the exhibition, some email exchanges where the two questioned the nature of the photos, the poses adopted by their grandparents and their companions, were published; they challenged the images they have to understand their past and, along with it, the more collective past of the country. The examination of the pictures corresponded to the analysis of their personal origins, in the attempt to deal with these hard evidences that must be exposed and narrated to be observed.

In Difficult Heritage, family and archival microhistory, primarily based on vernacular photography, became a window to investigate a colonial national past, often subject to processes of denial, mythification, or, more commonly, oblivion. The concepts of historical amnesia and aphasia were the key points from which the entire reflection originated. On the one hand, there is the incapability to remember; on the other, the impossibility to verbalize a traumatic memory. More precisely, the exhibition got inspiration from the definition coined by scholar Sharon Macdonald, who published the book Difficult Heritage – Negotiating the Nazi Past in Nuremberg and Beyond. Macdonald highlighted how the word “heritage” encapsulates many historical events that have contributed to shaping the identity of a territory and its people, but how the message often communicates achievements, victories, and pride. Less commonly associated with the term “heritage” is an open interpretation that can publicly acknowledge violence, wars, and colonialism, among others, and consequently trigger a collective process of recognition, acceptance, and modification. “Difficult heritage” thus appears to be a more precise definition that does not erase the critical aspects of a country’s history but rather highlights its complexity.

Memory, shaped by a centuries-long variety of events, ideas, and personalities, cannot eliminate, much less ignore, the darker moments of history. The exhibition attempted to open a box hidden in a dark corner of the house and study the material inside. In this analytical activity, Fiorio and Margani initiated a process of reconfiguration of their memories and constructed a narrative that revealed the difficulty of owning it, made even more complicated by being part of family affections. What the display suggested was the willingness to inhabit that specific fascist and colonial past to build an alternative story.

The entrance to the Remont Gallery was characterized by a room where the photographs recovered by the two artists were located at the center: four large portraits of their grandparents hang mid-air, three in military attire and one in civilian clothing. The images were printed on a fabric support that revealed what was happening around them, as if they were ghostly apparitions or memories about to be developed. In a play of visual overlays, they connected individual pasts, allowing the faces to change as the bodies around them moved.

In this case, vernacular photography was the protagonist, bringing a reflection on the relevance of personal archives for a precise and more composite historical reconstruction. In other words, these archives were more than just a pile of old documentary photos; they were evidence of a mostly neglected chapter in Italian history that collective memory and academic inquiry have often struggled to address. Without pursuing artistic goals, this type of photography, which models everyday life and ordinary things, has often taken on the meaning of “familiar”, emphasizing the importance of domestic identity. It is precisely the search for that identity that Fiorio and Margani tackled.

The physiognomy of those wind-blown portraits, far from solid, far from vivid, was indeed familiar, belonging to distant affections. Showcasing those faces could be considered an official act of transcribing history, where those atrocities consciously acquired specific names and faces. Simultaneously, the identities of those men overlapped, allowing the characteristics of one to pour into those of another in a continuous process of metamorphosis. In this sense, the colonizers contributed to elevating the discourse from a strictly personal memory to a collective one that retrieves a difficult legacy of Italian heritage. The construction of plural identity through the private narrative of colonialism was thus the principal reflection that the exhibition brought.

Always hanging high and closer to the ceiling were smaller photographs of various dimensions, showing images of conquered villages, Eritrean and Ethiopian peoples, generals parading on horseback in African lands, handwritten documents, Red Cross trucks, and indigenous groups dressed in fascist uniforms. Traces of the past fluctuated above the heads of the audience emphasizing, on the one hand, the weight of those events and their presence in the history of the Italians, and on the other, almost emulating the process of picture development through a darkroom. As it happens after exposing photographic paper to light upon which the photographic negative is projected, the support is immersed in chemical liquids, and the paper is then hung, waiting for the images to manifest.

Here, in a synergic effort, there was an attempt to develop a historical consciousness and come to terms with the Italian colonial past that characterized the country from the late XIX to mid-XX century with a persistent invasion and administration of the African continent. This colonial legacy continued to be denied or observed through an apologetic reading of the “Good Italians” in the post-war period. It is a history that is still far from being acknowledged. “The main reason […] can be traced to the behavior of the ruling class, which, after the signing of the Peace Treaty of Paris (February 10, 1947) that definitively stripped us of the colonies, refused to initiate in the country, as has been done in other nations with a colonial past, a serious, comprehensive, extensive, and definitive debate on the phenomenon of colonialism.” Just consider, as an example, that the admission of the use of asphyxiating gas in Ethiopia, where concentration camps were built, was only acknowledged in 1996 by the Ministry of Defense, not without reluctance or softening. Italy is not second to any of the colonial powers when considering the massacre of people in Eritrea (1882-1947), Somalia (1890-1960), Libya (1911-1943), and Ethiopia (1936-1941). However, the absence of a Nuremberg for the African continent has buried the traces of inflicted violence.

Adjacent to this room, Fiorio’s photographs are exhibited. They were the result of My Fascist Grandpa, a project that originated in Borgo Rizza in Sicily in 2021–2022 during the Difficult Heritage Summer School promoted by the Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm (Sweden) and the University of Basel (Switzerland) as part of a collective project by DAAR: Entity of Decolonisation. From here, A Difficult Heritage: Visions from the Family Archive knew its origins.

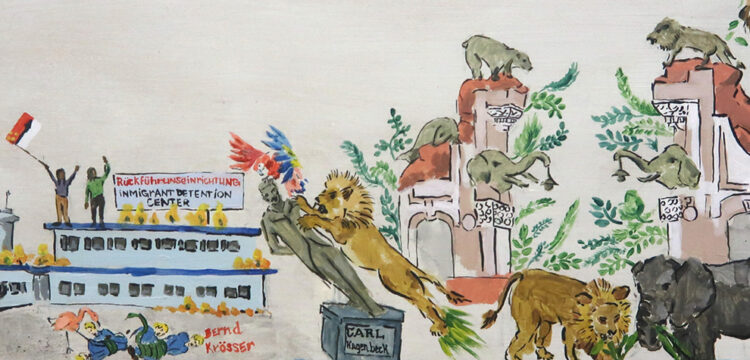

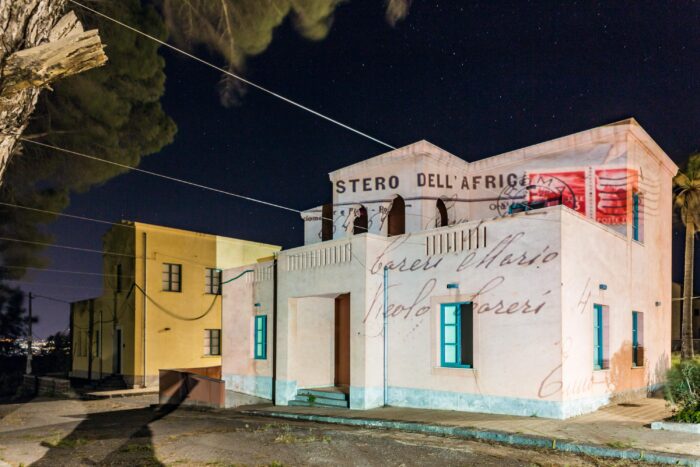

Borgo Rizza, located between Catania and Siracusa, is a small center in the Tummarello district in the territory of Carlentini, built according to the project of Pietro Gramignani between 1939 and 1940 by the ECLS (Ente di Colonizzazione del Latifondo Siciliano). Recently, the village has been restored thanks to European Union funds and is now completely uninhabited. Like many similar villages, it is characterized by a central square and the main fascist buildings, symbolizing the union of temporal and spiritual power, including the town hall, the church, the school, and the barracks. Here, Fiorio and Margani began a project to analyze the territory by interviewing people still living nearby who looked at the architecture of this place, mostly reduced to ruins, with familiarity and a certain degree of affection. Right here, on the dilapidated surfaces of these buildings, the two artists use their archives to interact and bring them back to life. The projection of some of the photographs showed at the Remont Gallery in Belgrade found their first use here, visually embracing almost all still-standing structures.

The operation aimed to understand how to relate to Italy’s colonial past, but here, history was in close dialogue with the territory. Some reflections were opened for inhabiting and reusing fascist places, which are significant themes of contention in the contemporary debates. It also explored how to connect past traumas with a present that often looks at them as objects of revival. Just as in the Tuscolano district of Rome, Borgo Rizza also carries the memory of a fascist martyr. In 1940, the village was dedicated to Angelo Rizza, who was killed in 1921 in Piazza del Duomo in Ortigia by some subversives. Since then, faith in Duce’s Fatherland must be remembered through a specific urban portion and well-defined symbols.

However, this time, workshops and public discussions led a group of scholars, academics, and artists toward sharing stories, memories, historical insights, and possible ways to engage with areas that explicitly bear witness of a problematic past. Moments of exchange were also present at the Remont Gallery with a public program that involved the Serbian audience, highlighting points of intersection between the Italian and the local past.

The public program was devised to establish a cultural bridge between two nations that, at different junctures, grappled with historical amnesia and aphasia. By inviting Serbian artists Vladimir Miladinović and Vahida Ramujkić to share a presentation on their practices with the wider public, the exhibition sought to foster a confrontation of methodologies to work with personal archives and negotiate with difficult memories and narratives. This collaborative exploration transcended the specific investigation of Italian colonialism, evolving into a more comprehensive analysis that desired to interconnect disparate territories and political contexts.

A pivotal component of the public program comprised two workshops. The first, facilitated by Fiorio and Margani, delved into localized personal narratives, inviting participants to share their stories, artifacts, and familial recollections. The second workshop, developed in close dialogue with Belgrade-based historian Milovan Pisarri, was co-conducted by Resistenze in Cirenaica, a collective active in the homonymous Bolognese neighborhood where they are carrying on an work on the Italian colonial repressed past and its implications on the present. Leading the participants across the city, the activity concentrated on institutionalized memories embedded in the public sphere.

A meticulous examination of the cityscape unveiled echoes of the past permeating the urban buildings. This past is not only present in the famous remnants of NATO-bombed structures in the city center, or in the brutalist architectures of Novi Belgrade, but also in the imposing Saint Sava Church on Vračar Hill—the largest Orthodox church in Serbia and, more in general, one of the largest in the world—and the recently erected monument to Stefan Nemanja, founder of the Serbian state and the Nemanjić dynasty, both emblematic of the historical legacy of Great Serbia.

Cities, as observed, manifest as maps wherein multiple temporalities coexist, compelling a rigorous interrogation of the contemporary moment. In the case of Belgrade, the urban landscape now incorporates the ambitious Waterfront development project, ostensibly positioned as a mechanism for urban and economic revitalization. However, the neighborhood was constructed through extensive speculative practices during the tenure of President Aleksander Vučić, the leader of Serbia’s far right governing party. His recent re-election in December 2023 precipitated public unrest, marked by fervent calls for his removal.

Conclusively, the exploration of the territory and its intricate tapestry of symbols serves as a potent tool for comprehending and re-narrating a national history, paralleling the approach adopted by Fiorio and Margani in the context of Sicily. A projection of Borgo Rizza on the Remont Gallery’s stairs concluded the exhibition in Belgrade, guiding the audience toward the exit. On the external facade, two large images from the artists’ archives unfolded along two window openings corresponding with the first floor. Here, the photographic objects represent precious testimonies that require constant revisiting and re-interpretation to consider “[…] what is ignored or overlooked, and how agency is accorded—all of which can be seen as constituents of what is sometimes called ‘historical consciousness’.”