Comradeship, Love and Heroic Constellations

A proposition for radical love, a call for radical heroes, in the name of social justice and anti-fascist resistance

Aria Spinelli’s introduction to the recently published volume Shaping Desired Futures (NERO and BOZAR 2018) touches upon the question of resistance and the formation of anti-fascist imaginaries in the present; a present in which racist forces, totalitarian governments and xenophobic attitudes multiply around Europe and the world. In her introduction to the volume Spinelli writes: “It is evidently within a void originated from the lack of Leftist politics that new forms of political organization have emerged. This volume tries to investigate whether within this void art and culture can contribute in creating a new imaginary.” What stands out here in relation to the urgencies of the present are the words “void” and the “new imaginary:” how to conceptualize the vacant space in which reactionary identities organize and develop and how to instead overflow this space with forms of anti-fascist desire?

Comradeship and Love

Writing in 1923, almost 100 years before the present time, the Marxist-feminist revolutionary Alexandra Kollontai speaks about a similar need to produce new social imaginaries within the then nascent Soviet Union. At a time when radical gender ideas were circulating in the Soviet public sphere, Kollontai grapples with the necessity to abolish patriarchal institutions through new understandings of gender that would correspond to the newborn communist society. In her text Make Way for Winged Eros, Kollontai contrasts two different concepts of love. On the one hand, within bourgeois society we learn to associate love with an all-embracing feeling towards one person that culminates in marriage. According to bourgeois love, then, for Kollontai, “love is permissible only when it is within marriage. Love outside legal marriage is considered immoral.” The ideal of the stable family unit prepares adjacent moral identities as, for example, to be a good family person was, “in the eyes of the bourgeoisie, an important and valuable quality.” Love outside marriage was considered—and especially for women—scandalous. On the other hand, to replace this “all-embracing and exclusive marital love of bourgeois culture,” Kollontai offers the concept of “comradeship love” which, for her, involves “the recognition of the rights and integrity of the other’s personality, a mutual support, sensitive sympathy and responsiveness to the other’s needs.” Correspondingly, communist society has to be built on the basis of solidarity and mutual trust, therefore these psychic dispositions need to be cultivated. Solidarity for Kollontai, however, does not only depend on the rational awareness of the common interests of the working class but also on the cultivation of intellectual and emotional ties linking the members of the collective under a common project. “Warm emotions,” for her, like “sensitivity, compassion, sympathy and responsiveness” are aspects of love that communist desire should embrace. Thus, while Kollontai hoped that negative love—that is the “sense of property” and “egoistical desire to bind the partner to one ‘forever’”—in Soviet society will vanish, this society would need to develop the positive, “valuable aspects and elements” of love. While communist love rejects the idea of love as property culminating in the family unit, it should welcome love as a “warm emotion” permeating proletarian affects, solidarities, bonds and sexual practices.

Alexandra Kollontai

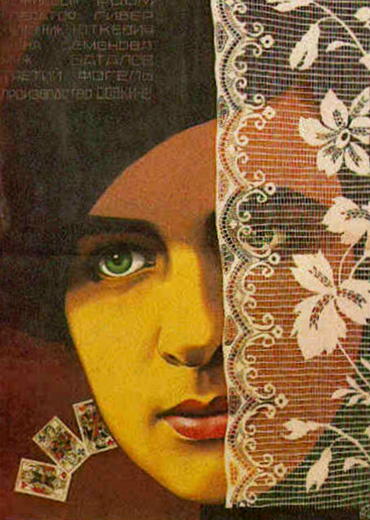

Kollontai argues that to abolish bourgeois patriarchy, then, comradeship love needs to involve three interrelated qualities (speaking primarily about heterosexual relations): first, the idea of “equality” that would put an end “to masculine egoism and the slavish suppression of the female personality;” second, the idea of “mutual recognition of the rights of the other” and “of the fact that one does not own the heart and soul of the other,” which for her was a result of “the sense of property, encouraged by bourgeois culture;” and third, a so called “comradely sensitivity,” which is “the ability to listen and understand the inner workings of the loved person,” an ability which “bourgeois culture demanded only from the woman.” These qualities set the ground upon which radical gender imaginaries would respond to the expectations and urgencies that the Russian revolution set out to accomplish. Moving to the domain of artistic production, an exploration of Kollontai’s debates around multi-partner comradely love can be found in the 1927 Soviet film Bed and Sofa (Третья Мещанская) directed by Abram Room; by depicting a ménage-à-trois, the film shows both the tensions and joys of possible new institutional arrangements, including the idea of multi-parenting, emerging out of the tentative rejection of love’s “oneness”—at least among intellectual communist circles. To go back to the start, the void in this film as well as in Kollontai has to do with the “present” of the early post-revolutionary years, in which the revolution had already taken place, yet gender roles remained bound to traditional bourgeois morality.

Bed and Sofa (Film Poster)

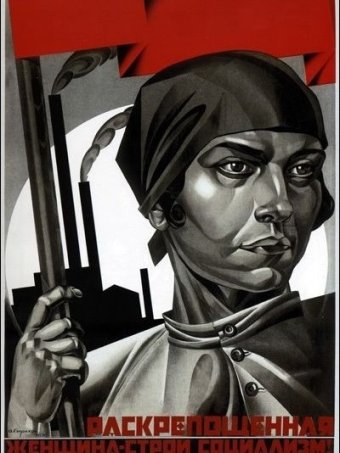

The Cause

Now, how does Kollontai relate with Spinelli’s volume and the anti-fascisms of today? I would suggest that what made Kollontai’s utopian project special was not so much its insistence on a radical reorganization of social relationships and institutions related to love but the framing of this reorganization within a common future vision, a future project that would liberate social relations. Love, more than everything, needs to be subordinated to what she calls “the more powerful emotion of love-duty to the collective.” While harboring a certain optimism that could lead to teleological thinking, Kollontai’s faith in the production of a new person within a project common for the oppressed articulates possibilities of larger unity. Today one can notice resemblances between Kollontai’s ideas and discourses on free love or polyamory, but the difference here is that these latter imaginaries are often not accompanied—at least in their mainstream articulations—by a desire to change the social relations of production, the distribution of wealth, the abolition of exploitative relations and the economic system that sustains inequality for the benefit of the few. What is missing from these lifestyle practices is a larger intersectional vision of the oppressed coming together under a common project.

Kollontai poster, International Women’s Day, Russia

Of course, the argument that working class, Marxist or communist politics, have lost their prestige—especially after the fall of Soviet Union—has been rehearsed repeatedly over the last decades. This melancholic rehearsal often occurs in fatalist terms, as Enzo Traverso poignantly demonstrates in his recent volume on left-wing melancholia (2016), and in ways that involve both lament and ironic distance towards contemporary “communist horizons,” to refer to Jodi Dean’s known concept (2012). Without wishing to enter the debates in detail, I would like here to speculate on how the abandonment of a radical imagination based on the grand narrative of communism and universal justice—including class, gender and species-based justice—has contributed in opening the void that Spinelli talks about. I would then suggest that for instigating affective bonds with these narratives, or Kollontai’s “love-duty,” we may need to rethink “dated” notions, including the idea of self-sacrifice and commitment to a cause as well as firmness in our anti-fascist ways of being. That would entail the eventual appropriation of heroic modalities for combating oppressive structures. It is in this idea of the “heroic” as both the endmost manifestation of the love-duty towards the oppressed and the initiator of affective bonds between them that we shall turn our attention on.

Heroes and their Monuments

Heroism, in contemporary art and critical theory discourse most usually refers to macho subjectivities, more-than-human representations and generally to banal, oppressive if not outright totalitarian figures. The latest Berlin Biennale We Don’t Need Another Hero was expressive of the anti-heroic sentiment of the political art of today; by being against the figure of the hero-saviour it rhetorically structured a more ‘flexible’ and explorative imaginary. In Baudrillardian accounts, the hero has been dismissed as an impossibility in a media saturated world (e.g. Franco Berardi, 2015) or, in critical art historical terms, it is often seen as the ideal figure promoted by fascist and Nazi art (e.g. Boris Groys, 2008). The celebrated disjuncture between theory and practice in theories around performativity reduces the heroic in narratives of fixity, purity and immovable intransigence while in queer theory the hero expresses mostly white, male, heteronormative or “cemented” ways of being. To make matters worse, the heroic contributes to monumentalizing and spectacularizing specific moments of history, selectively, in order to serve ideological agendas. And since monumentalization is usually bound to state policies and the production of national myths, the heroic is guilty of reinforcing dominant ideologies. The great hero-leaders of the nation, whose monuments are erected in public squares and whose bravery is exalted by the state, enable regressive, ethically-bound dichotomies between ‘us’ and ‘them’ through myths of national unity.

Heroism, irony, popular culture

There is no doubt that most of these critiques of the heroic are partly justified. Yet I will be arguing that the appropriation of the concept by reactionary forces should not entail its abandonment. Especially in our current conjuncture in which xenophobia and racism become state policies and have wide popular appeal in Europe and the world, heroic politics and its satellite concepts, including self-sacrifice, dedication, intransigence and risk, need a re-conceptualization. Inasmuch, capitalism, spectacle and racism are themselves enormously powerful institutions, one cannot beforehand exclude modes of resistance that would involve these qualities. Rather than discarded as totalitarian or macho, in Kollontai’s radical gender theories heroines and heroes would rather appear as positive figures. For her, then, the Revolution was not a mere performance of resistance but came out of the “bravery, self-sacrifice and heroism, and of tremendous faith in the victory of the revolution and the justice of the struggle” from the side of the oppressed; that is to say out of a total dedication to the idea of social liberation through which the bonds, identifications and love duties towards the revolutionary cause would spring.

Heroic Constellations

Rather than simply a personal affair that manifests in certain individuals, we could “socialize” the idea of the heroic, seeing it as a constellation that comes together in particular times and spaces producing socially-meaningful symbols. These symbols typically represent ideas both of transgression and justice (however these are interpreted) rooted in some commitment or dedication to the cause that the person or collective pursues. Transgression from assigned social roles, justice against injustice and firmness to the cause are all the qualities that the hero expresses and through which bonds with their politics occur.

In our context, ideally, heroic constellations would allow a radical democratic politics to emerge alongside the possibility of articulating a project common for the oppressed. It is not just a hero that inspires people to do things but the hero in context; a person or a collective committing in determined action and becoming a symbol for the larger idea they pursue. Of course, the idea the “hero” strives for needs to be socially produced in order to become meaningful; it may be the subject of endless argumentation and debate between political adversaries, it may be distorted, repurposed, shifted, reshaped to fit one’s politics. It is then the work of anti-fascist and radical democratic politics to imbue transgressive memories and political arrangements with resistant meaning and construct heroes whose commemorative rituals would allow the circulation of respective imaginaries in public space.

One thing however is true: the clearer the hero’s vision is the less it can be distorted when heroic constellations become part of public spheres. Qualities such as dedication, parrhesia and commitment enhance the hero’s vision and make identifications easier. The qualities of the hero’s visions can be read vis-à-vis Joel Olson’s discussion on the idea of “fanaticism.” In his prematurely finished yet influential work on the concept, Olson moves away from its dominant, pejorative use in liberal discourse by discussing the so called Garrisonian wing of the American abolitionist movement of the 19th century—a group “of self-defined fanatics.” These fanatics had a very clear and consistent vision of equality for all whose interpretation could hardly shift and slide: they were fighting for the abolition of slavery and in doing so they used transgressive methods that involved the breaking of church services and the persistent pro-abolition preaching in any given opportunity. The fanatic, then, as the figure who would totally commit to an idea, can provide less troubling and less poly-semantic identifications through their politics. Like fanaticism, heroism is “neither inherently democratic or undemocratic,” it refers to a mode of political articulation that turns the enunciator into a devotee to a cause.

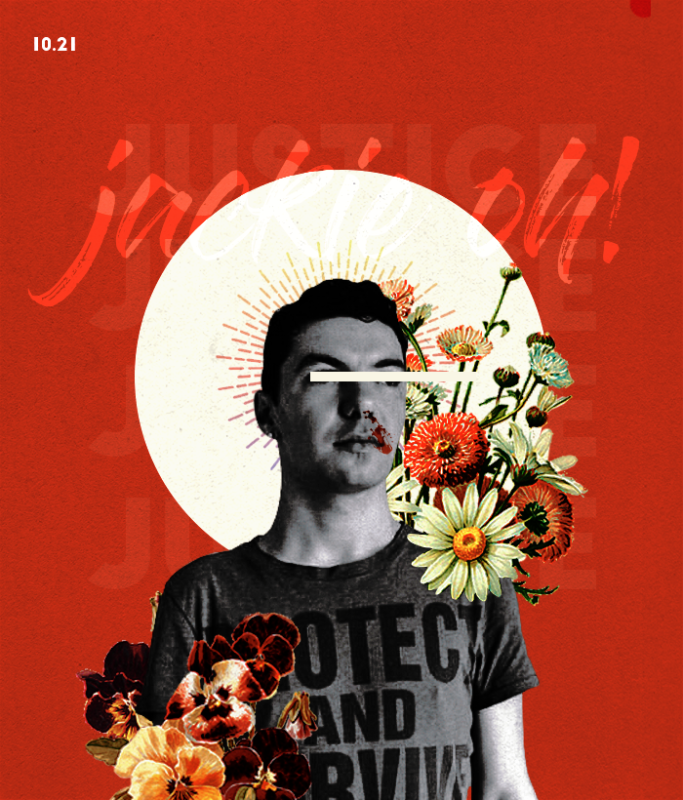

Zak Kostopoulos. Saint

Some months ago, Zak Kostopoulos, a drag queen, HIV positive and LGBT activist was murdered in the center of Athens by an angry mob of macho men and the police. The incident was initially presented by the state and the media as an accident, or even a form of rightful vigilantism, following a supposed attempted robbery of a jewellery. According to this narrative, Zak tried to rob the shop in daylight, got caught and as a result was “punished” by the owner, the mob and the police who literally beat him to death. As part of his public vilification and media-spectacle trial after his death, Zak has been named a “junkie” and a “robber.” This process of stigmatization further included references to his sexual preferences, creating thus a chain of signifiers, in which homosexuality, HIV positive persons, cross-dressing, drug-use and activism would be expressive of deviant or illegal behavior. Zak was produced as a figure standing for a “transgressive other” that threatens society’s bourgeois morality, whose ideal is still based on what Kollontai called the “good, family man.”

However, soon the whole narrative of the threat proved to be false, initiated by the ones who killed Zak in the first place and subsequently uncritically recounted by the media. What was proven following witness reports and medical post-mortem examinations was that Zak neither attempted to rob nor used drugs but was simply lynched to death by the mob; he entered the shop probably to cover himself from a nearby incident of bullying against him. The initial fake news was only reversed after the committed effort of his friends and fellow activists to bring justice and give publicity to the case.

In the case of Zak Kostopoulos, we have different varieties and intensities of the heroic at play coming together in a single event in what we can call a “constellation of the heroic.” Once the concealment efforts by the media and the police were revealed, gradually, his transgressive otherness came to be associated in public debate with different aspects of justice. Under this reversed narrative, his murder was now seen through the lens of martyrdom and self-sacrifice for a cause; leading a different life from what is considered to be “normal,” transgressing the boundaries of the acceptable and, even more, being a prominent voice for LGBT and HIV-positive people were all aspects of a just actuality whose very risk-taking led to an unjust death. Zak then life and death revealed a consistency between words and actions, in which truth was manifested in the way of life itself and where this very truth-telling bore consequences to the enunciator’s physical being (Foucault, 2010). His death then was heroic in the expanded sense of the word; it revealed a “truth” turning life itself to a site of justice. In turn, for this very constellation to be activated, the courageous, determined and, similarly, heroic efforts of his friends, lawyers and queer community activists was required. This constellation of heroic values opened debates in the Greek public sphere ranging from the treatment of HIV positive people to the rights of sexual minorities.

Not Lost Heroes?

For reclaiming the void that neo-reactionaries occupy, to go back to Spinelli’s text, the cultural and artistic pathways for new radical imaginaries would then need to involve or at least not disavow a politics of heroism in its literal, even unambiguous, sense rather than through ironic distance. We can indicatively refer to several heroic constellations, events that mobilize aspects of the heroic as they become symbols for higher ideas expressive of social liberation: from the high profile cases of Chelsea Manning and Edward Snowden, from Anna Campbell to Haukur Hilmarsson and the numerous murdered volunteers in Rojava and Afrin, to the Greek rapper Pavlos Fyssas whose murder in 2013 by neo-Nazis in Athens seriously affected the party of Golden Dawn. In these instances, the heroic is a socialized construction and a point around which radical progressive politics and claims can be articulated in public debate in the name of social justice. Here, these individuals, would often not perceive themselves as heroes; the heroic is essentially a socialized establishment, a symbol for an elevated, often utopian, idea that can inspire, consolidate bonds and turn Kollontai’s love-duty into a tentacular, “warm emotion” among the oppressed.