Bodily Memories

From the 35th São Paulo Biennial “Choreographies of the Impossible”

How can bodies in movement be able to choreograph the possible, within the impossible? The proposal for the 35th Bienal de São Paulo emerges as a mutual project around multiple possibilities to choreograph the impossible. As the title already suggests, it is an invitation to radical imaginations about the unknown, or even about what figures as im/possible.

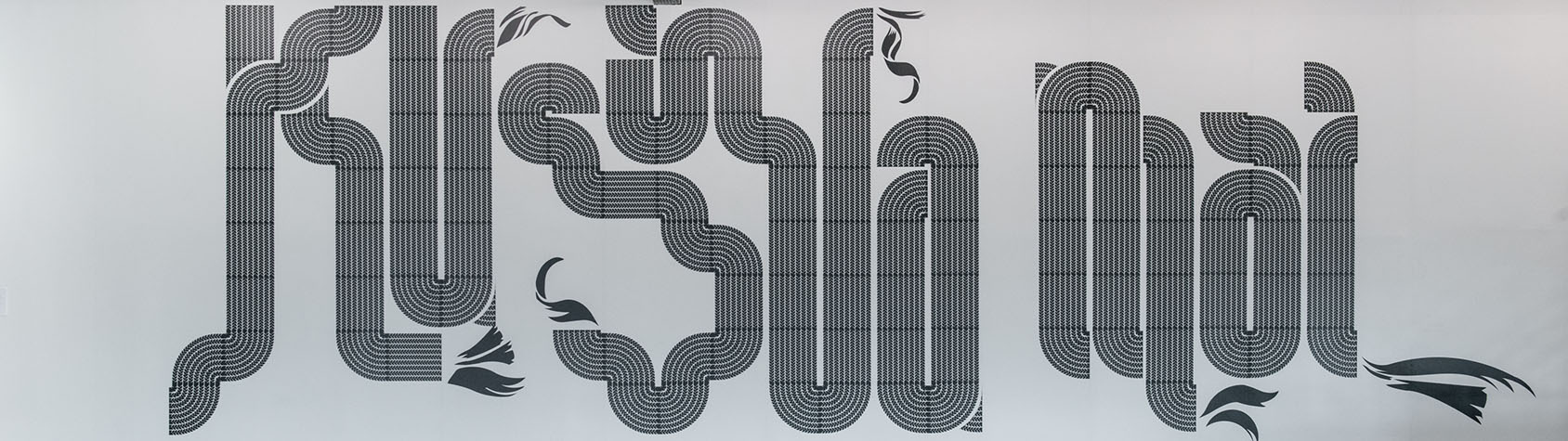

A tactile memory survives the passing of time, from the opening of the 35th São Paulo Biennial to the moment I am writing. The impression of a thick line and a curvy texture draws an irregular pattern on the banner fixed at the entrance of the three-storey Ciccillo Matarazzo Pavilion, immersed in the Ibirapuera park. The Biennial’s title is a stylized version of African brides that reads “Choreographies of the Impossible”. Bearing cultural and political meanings for the history of the African diaspora, the brides are also the signature of Nontsikelelo Mutiti’s work, the artist and designer who conceived the biennal’s visual identity. Their twisted shapes introduced me to the unrestrained movement of the show inaugurated at the beginning of September, which took over the modernist architecture of Oscar Niemeyer and reconfigured its rise to the top in a multidirectional dance depleted of any protagonists. Since the beginning of their appointment, the curatorial team formed by artist Grada Kilomba, anthropologist and curator Hélio Menezes, curator Diane Lima, and art historian and museum director Manuel Borja-Villel have reconfigured their collaboration into a “collective” privileging horizontal working methodologies over the figure of the demiurge-curator. Without hiding the existence of moments of tension but also of fertile reconciliation, this partnership produced a biennial that stands in antagonism with western culture’s oculocentrism.

Choreographies of the Impossible is a show that must be experienced not only “with” the body, but especially “departing from” the body. Entering the biennial, the kinetic sculpture Mimenekenu É Lá Tempo (2023) by French-Brazilian artist Ana Pie and Kwa Nkisi Mutá Iméime, a religious exponent of Candomblé, pays homage to Nkisi Tempo, a deity from the mythology of West African Yoruba people. Its spiraling movement creates an immediate strong contrast with the net lines of the railway track built by the Ghanaian artist Ibrahim Mahama, in a Parliament of Ghosts (2019).

In Kidlat Tahimik’s wooden sculptural complex, ancestral mythological figures of indigenous Brazilian and Philippine’s population clash with colonial and imperialist narratives, impersonated by fictional characters from the Hollywood film world, suggesting a battled arena brutally interrupted by the self-contained presence of Torkwase Dyson’s minimalist and abstract sculptures, that cut vertically the elliptical staircase of the pavilion. If these variations of rhythms and intensities among the works installed at the ground level of the Biennial Pavilion produces a pleasant sense of abandonment to the composition created, this statement loses consistency when applied to the second and third floors of the exhibition. Following the path designed by Vão studio, the visit proceeds from the first to the third floor and then descends to the second, inviting the audience to cross the external green space that surrounds the pavilion.

The third floor presents an unexpected selection of bidimensional works; the asset of the white cube display model seems to take over the space again, for a while restoring the predominance of an unembodied spectator. However, in these rooms we encounter some of the most surprising pieces of the biennale. A document testifying to the life of Xica Manicongo, the first transgender person ever-recorded in Brazil, shows how micro-histories of resistance have been present in the country since the 17th Century, at least. In the following room, Bolivian artist Melchor María Mercado’s watercolors dated two centuries later leave to posterity a rare and intimate counter-narrative, by opposing her culture to the one of the colonizers.

During the press conference, the biennial’s curatorial team has declared that the works have been assembled based on poetic associations and affective affinities, rather than for thematic similarities or chronologies. Still on the third floor, Rosana Paulino’s archetypical black female figures of her 2019 painting series Búfala, Senhora das plantas e Jotobá (Buffalow, Lady of the Plants and Jotobá) held a specular position to Aline Motta’s work on her maternal lineage, A água é uma máquina do tempo (Water is a Time Machine), 2023. Guadalupe Maravilla’s “healing machines” are installed in proximity to Rubem Valentim’s Templo de Oxalá, 1977, while Elda Cerrato’s abstract series of paintings that inspired her short film, Segmentos_CPV: Okidanokh (1964– 2022) materialize her fascination for hallucinations and esoteric projections.

Notwithstanding the appreciable intention behind the curatorial team’s choice to not conform to the pressure of intelligibility in regards to clarifying the connection among the artworks, thus allowing for embodied meanings to reach to the surface, the downside of this curatorial strategy has been that some exceptional works completely felt off sight of the visitor. This is the case of Sammy Baloji’s abstract wooden panels and video work, Tales of the Copper Cross Garden, Episode 1, from 2017, where images of the exploitation of copper factory’s labor overlapped with catholic liturgical songs addressing the effect triggered by Belgian decolonization in Congo. On the second floor, the artworks installed seemed at times even isolated presences, with a series of monumental installations one after the other. Castiel Vitorino Brasileiro’s installation share the space with Igshaan Adams’s polymetric maps, while Daniel lie’s yellow drapes contrast the blue color of Luana Vitra’s sculptural intervention.

Throughout the biennial, temporary areas have been created to generate collective and spontaneous meetings among visitors. This is the case of the kitchen of Cozinha Ocupação 9 de Julho, the community kitchen of the Movimento Sem Teto do Centro de São Paulo, which has become one of the main refreshment places of the Biennial. Another is the assembly space created by Nadir Bouhmouch and Soumeya Ait Ahmed, both members of the Le 18 collective from Marrakech, which many have recently met at Documenta 15. Finally, the Lesbian Sauna, a multifunctional space where participatory activities are planned for the whole the duration of the biennial. As the curators write in the work’s presentation text, these spaces are “nourished by the choreography of those who occupy it.”

Indeed, the body and its associated choreographies are the omnipresent spectrum that trespasses all the biennial rooms. At the ground floor, footage of the dancer and anthropologist Katherine Dunham, shot between the 1940s and 1960s, dialogues with the avant-garde film Meditation on Violence (1948), in which the camera of director Maya Deren is perceived to participate in the movements of performer Chao-Li Chi. At the end of the first floor, documentations from the 1990s and 2000s we find the choreographies of Luiz de Abreu, a researcher and performer known for using dance as a tool for deconstructing the stereotypical identities of the black body.

On the second floor, dances and social scenes linked to the lesbian and feminist movement which were violently repressed during the years of the dictatorship in Brazil (1964-85), immortalized by the photography of Rosa Gauditano. Dancing bodies are also the mechanized curtains of Diego Araúja and Laís Machado, or Sonia Gomes’s fabric sculptures installed next to Judith Scott’s objects covered by colorful strips. As the author Leda Maria Martins suggests “aqui, numa coreografia de retornos, dançar é inscrever no tempo” (tr. here, in a choreography of returns, dancing is inscribing time): through these imperceptible movements, the 35th São Paulo Biennial destabilizes those Western centric axes visitors who fly from Europe to Brazil to visit the show revolve around to learn and understand contemporary art.