Flush Memories

A workshop for decolonial choreo/graphics: a conversation with Marie Moïse and Mackda Ghebremariam Tesfau’

On September 7th, 2023, and as part of the collaboration between If Body and Short Theatre, Marie Moïse and Mackda Ghebremariam Tesfau’ held Memorie da Sottopelle. Laboratorio di Coreo/grafie Decoloniali, a workshop originated within the project Decolonizzare il Sapere. Pratiche di Femminismo Antirazzista.

The following conversation delves into the issues addressed by the work of the two researchers, activists, and translators of the book Memorie dalla Piantagione: Episodi di Razzismo Quotidiano by Grada Kilomba (Capovolte 2021). They question how words and concepts of decolonial feminism can be transformed into verse, movement and gestures, as well as how the feminist power that lies between liberation, healing and the re-articulation of self-defensive mechanisms, can take the form of a new collective consciousness.

If Body is a public visual and performing arts program that focuses on the body as an artistic language and learning methodology based on experience and participation. Conceived and curated by Sara Alberani and Marta Federici (LOCALES), it presents new performances, talks, workshops and exhibitions that explore the cultural, social and political meanings associated with body and corporeality throughout six events. The first edition involves interventions by Amelie Aranguren (INLAND – Campo Adentro), Marie Moïse e Mackda Ghebremariam Tesfau’, Pauline Curnier Jardin & Feel Good Cooperative, Adelita Husni Bey and Holly Graham.

For this occasion, a series of interviews are conducted by Chiara Pagano with the artists of the If Body 2023 program to delve into each specific happening.

Chiara Pagano: How did your collaboration begin?

Mackda Ghebremariam Tesfau’: We met because of our common interests towards anti-racist activism while presenting a book that Marie translated, at a social space in the province of Vicenza. From then on we kept collaborating, initially with a group of people invited as experts by an association, and then by working on the translation of Memorie dalla Piantagione by Grada Kilomba. In the meantime, we’ve held many classes, gatherings, and presentations. In short, we work together very often.

Marie Moïse: I agree.

In the past weeks, on the occasion of the If Body program and thanks to a collaboration between LOCALES and Short Theatre, you brought a workshop at Teatro India: Memorie da Sottopelle. Laboratorio di Coreo/grafie Decoloniali. Can you tell us more about this project? How did you come to it, and what desires move it?

Marie: Our collaboration is in the field of decolonial political theory practices. In this context, the idea of exploring texts from a decolonial perspective emerged; we wanted to question and understand what it entailed. As we delved into this, it aroused the desire to explore a different way of engaging with texts, one that goes beyond the conventional practices—and when I say “conventional” I mean normed by the White West societies—of establishing a relationship between the individual “author” and the individual “reader.”

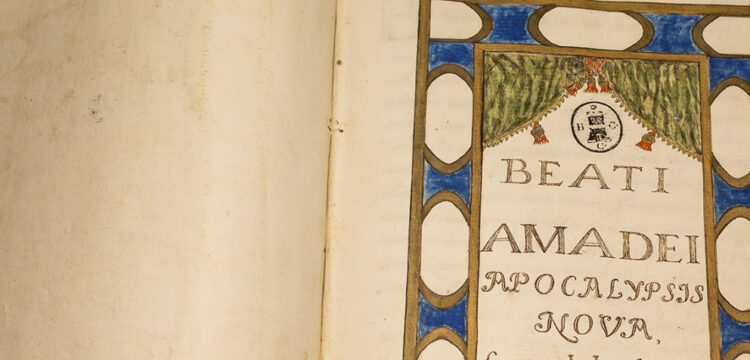

We approached the experimentation of other formats capable of transforming the relationship between the writer and the reader into a political one, thus decolonial because we aimed to activate a work of deconstruction and embodied investigation of the content within texts, particularly focusing on books authored by racialized women in Capovolte’s catalogue. The idea was to breathe new life into the act of translation, transforming it into a catalyst for forging fresh political connections.

Mackda: It’s important to emphasize that knowledge plays a crucial role in the exercise of colonial power. Therefore, breaking down the idea that knowledge is a single, unchanging entity, constitutes in itself a decolonial approach to the act of studying. In this instance, we focus on the book as the object of power, and we do it by questioning Capovolte’s catalogue, and specifically their series about intersectional theory. However, the same work can be done in contexts that encompass various other critical theories.

Regarding this, I’m interested in understanding how the book itself is transformed through what you call “choreo/graphic” practices and, therefore, what role the body plays in this transformative process: the body that is present—yours and those of all participants,—but also the body that is evoked, the collective one, of all the writers you call within the practice of Memorie da Sottopelle.

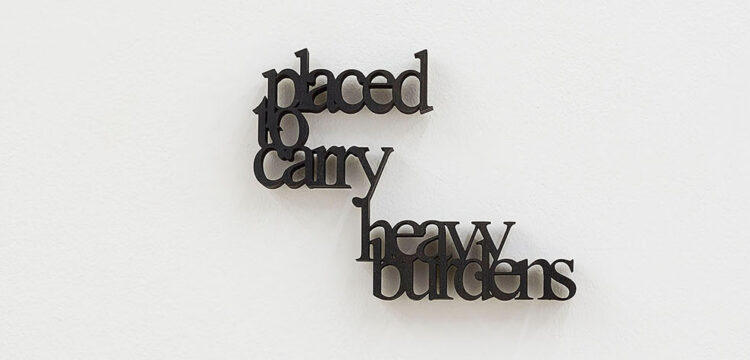

Marie: To speak of “choreo/graphics” is to directly link the book to what the body is capable of, in terms of creativity and experience. This idea implies that the possibility of reading, and thus interpreting a text, does not only come through my study, and my capacity for conceptual-rational-theoretical understanding of what I’m reading. On the contrary, it is achieved by surfacing the memory of my lived experiences and valuing it in the process of interpreting both the text and its contents.

The work we do in this workshop is aimed at a collective understanding of what the text says, starting from the lived experience of individuals and relating the different experiences to each other, to give meaning to the words we read.

That said, we also work in the opposite direction, from the text to the body. We have made a specific selection of readings: partly from the poetry series—not a casual choice—of Capovolte, which is the “La Po Ra” (LAtitudini, POesia, RAccontarsi—latitude, poetry, to tell one’s story); and partly from the “Ribelle” and “Intersezioni” series, in which there are texts more “akin” to the non-fiction category, but dense with lyrical and evocative pages since they’re produced by decolonial women authors.

In the workshop, we would like these pages to generate an idea of decolonial feminist theory that doesn’t solely rely on canonical nonfiction writing but rather emerges from the lyrical and poetical realm. That’s why we propose poetic essays: to engage the body…the body which, in turn, we perceive as a text on which memories are engraved, through languages that are other than the hegemonic one, of the rational word.

Mackda: What Marie is saying, about the body as a text, is crucial. Often, what is written on the body was not written by the person themselves. In the sense that the body is read from the outside: other meanings are ascribed to it by others. Choreo/graphy, in this scenario, becomes a way to reclaim what one’s own body communicates.

In your workshop description, what are referred to as Memorie a fior di pelle (flush memories) become “fugitive lines to horizons of change.” Quoting Nathaniel Mackey—“to accentuate the fissure, the fracture, the incongruity, the rickety, imperfect fit between word and world, is to open presumably closed orders of identity and signification; highlighting and inhabiting discrepancy, engaging with it, rather than seek to ignore it.”

Mackda, you recently had a conversation with Fred Moten in the context of Short Theatre. During your conversation, you touched on the “fugitive”, a topic that is strongly present in your workshop. What does this fugitivity mean to you?

Mackda: Reading a text collectively is a way of escaping the solipsistic dimension of reading, rejecting the one-to-one relationship linked to the traditional way of doing interpretation. In a broader sense, for me, fugitivity or rejection, are generative dimensions in terms of denying what is given.

In his way of understanding blackness as fugitivity, Fred opens up the possibility of getting out of the “anti” dimension: anti-racism, anti-fascism, anti-sexism. In this sense, it becomes a strategy to think about autonomy, I would say. After all, even historically it has to do with this: with the possibility of escaping the norm that wants you in a place, and instead going elsewhere, to create another norm that is self-constructed, given autonomously.

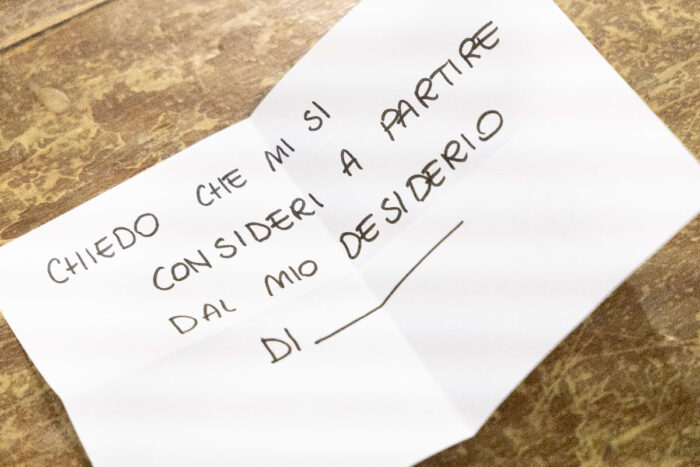

Marie: I’d like to elaborate on the points you both raised and introduce another aspect of the word addressed in the context of our workshop. We work on a word that is situated, just like the words of the authors whose texts we bring into the lab. These authors all have racialized backgrounds, with colonial histories. Therefore, our goal is to address this specificity: we encourage participants to position themselves and question their position of power, “the place of the word,” to mention Djamila Ribeiro’s text, one of our references.

An exercise in the workshop involves an invitation to produce out of the formula “I see you…I feel….”, a lyrical reflection. This approach is a method to encourage participants to engage in a relationship with others and to examine their feelings from their unique perspectives.

Regarding the concept of fugitivity, I think it originates from the history of colonization. Therefore, I perceive the power of a fugitive word within our workshop, as a word intertwined with the historical roots of racial liberation and colonialism. It’s important to note that for sure, this concept may not carry the same significance for all the participants in the workshop, but one of its fundamental aspects is that those who embody the history of this fugitivity can express it through their bodies: this is an invitation to stay and engage, rather than an invitation to escape. It’s about deserting the possibility of enunciating a word of power, of privilege.

Both of your backgrounds are related to theory and research. How did you approach artistic practices that investigate the body, and what potential do you think they have concerning the issues you address in the workshop?

Marie: It is difficult to reconstruct how this came about. Both Mackda and I have backgrounds in theoretical production work that eventually evolved into artistic endeavors. Art plays a fundamental role in decolonial practice. When it becomes involved, it opens up practical possibilities of transcending the linearity of change—a perspective on time that I believe is often Eurocentric. The need to introduce art then, serves as a critical element for questioning and decolonizing political horizons. It gives transformative dignity to the practice, which has no predetermined end but which spills outward starting from the body, from the self, from a transformation of the flesh.

During the practices you propose, the participants involved create new alliances. There is thus a component capable of generating an empathetic, affective, relational fabric, where words likely become touch-words that caress the body of the other…

Marie: What makes this workshop particularly powerful is the deep exchange that takes place among participants who have just met. They connect their emotionally charged life experiences, challenging the conventional idea of “don’t air your dirty laundry in public.” In this space, the traditional concept of family, characterized by whiteness, nuclear structure, heteronormativity, cisgender, and Western ideals, is dismantled. Participants realize the importance of sharing their experiences, both on a personal and political level.

When we leave the space of the work, we bring with us the memory of the relationships we have discovered, into the rest of the world.

The workshop format is today often used as a tool for practicing activism and art. How does the academic world respond to this?

Marie: Certainly, the academic world is the least receptive, but when we’ve had the opportunity to bring workshops into universities, the results have been incredibly impactful. Conducting laboratories within academia has meant challenging knowledge production practices in relation to physical spaces as well. For example, in Bologna, we worked in a university classroom by rearranging all the chairs and tables, deconstructing the hierarchical and vertical spatiality of knowledge that places someone in a teaching role and others in a learning role. We used collective and choral voices, as well as dance. It was powerful to see professors and students working together, reevaluating power dynamics and the relationships of politically embodied lives. If academia truly had an awareness of what was happening within its walls… perhaps it wouldn’t be called academia anymore.

It has been more than a year now that we have been conducting this workshop, and to me, it’s a success. We received numerous requests and invitations, and the outcomes of our work are truly powerful. While in the beginning, we had some uncertainties about what to expect, now it’s almost a confirmation that, nonetheless, shakes me every time: people are capable of transformative creative expression, and we encourage them to embrace its full political potential.

The workshop aims to serve as a territory for experimentation, a safer space compared to others, where we can think and create a language that can be brought to public squares, where we publicly share our discourses and advocacy for our causes.

Our concern lies in preventing decolonial feminist publications from becoming commercialized and stripped of their political essence in this current historical phase. Instead, we aim to reintegrate these texts into the public sphere. By “public space,” we mean a broader concept of a meeting ground for bodies that were not originally intended to come together, fostering unexpected encounters that generate transformative actions. We use these workshops as a starting point to rethink public squares, politics, and social transformation in its broadest sense. The relationship with texts, in this rethinking, is an important step toward change.

A year since the launch of Memorie da Sottopelle, we are working toward structuring new workshops that introduce other texts from Capovolte, which is currently expanding its publications toward other keywords such as “ecofeminism.” For instance, it’s in the pipeline a workshop that will focus precisely on the ecofeminist perspective, and another one related to what Conceição Evaristo—among the authors we reference—calls “scrivivencia,” that is, about the narrative word: that word that is always the word of the self.