Beyond the Singular Earth

Pluriverses, Porosity, and the Politics of the Common in “Earthly Communities”

Beyond the Singular Earth: Pluriverses, Porosity, and the Politics of the Common in Earthly Communities explores how the exhibition Earthly Communities (Kunst Meran Merano Arte, 2025) reimagines community through postcolonial, ecological, and performative practices. Drawing on Achille Mbembe’s notion of the “earthly community,” the text follows how artists from Abya Yala and its diasporas enact forms of coexistence that unmake the human–non-human divide. Through close readings of the exhibited works—with particular attention to the performances by Amanda Piña and Alexandra Gelis—the essay traces how artistic and curatorial gestures move across and between relational epistemologies, opening spaces where knowing and sensing become shared, porous, and plural. It adopts a hybrid, situated mode of writing, to reflect on how these gestures enact porous ethics of coexistence—inviting a movement beyond identity toward the shared, vibrating field of the pluriverse.

Fade in

Curated by Lucrezia Cippitelli and Simone Frangi at Kunst Meran Merano Arte (22 June–12 October 2025), Earthly Communities [1] was a composite entity, what Achille Mbembe describes as a “relative sum, at a given moment, of multiple combinations” (2024, 22), finding both its possibility and its dissolution in the embrace of incompleteness and the ephemeral. As the planet’s space tightens along with its resources: water, air, metals, fuels, the biodiversity of ecosystems, while identities, time, and humanitarian corridors contract, Earthly Communities emerges as a gathering of expanding existences, moving through a relational rather than identitarian logic. Drawing on the thought of Cameroonian philosopher Achille Mbembe, whose influence runs through the exhibition’s very title, [2] the project gathers artistic and curatorial practices that treat relations as the “ultimate expression of who we are” (Mbembe, 2016, 290–291). The title itself serves as a quiet reminder that “we are always already present with others […]” (Mbembe 2024, 8). In the exhibition, artists from Abya Yala [3] and its diasporas approach reciprocity as a way of living—a practice of giving and returning, [4] of ecological resistance, of repair. Across its three floors, Earthly Communities invites us to live exposed: to porosity, to stretch and fragility, to the unruly blend, to friendships out of time—to the slow dissolution of the self into the universe, against the universal and its universalism.

Stepping past the worn languages of identity, difference, and otherness, as the very concepts that have long upheld borders, justified extraction, and fed imperial desire, the artists Minia Babiany, Marilyn Borro Bor, Carolina Caycedo, Luigi Coppola, Etienne de France, Alexandra Gelis, Eliana Otta, Mazenett Quiroga, Amanda Piña, Sallisa Rosa, and Samuel Sarmiento answer what Achille Mbembe (2024, 137) names today’s frontierization [5] with a shared, if diverse, commitment to the in-common. Rather than drawing the other into safe enclosures—and flattening difference in the process—we are invited to turn outward, towards “the energies of the universe itself, those capable of holding the totality of life and transcending death, in a process inevitably pushed beyond the notion of identity” (Mbembe 2024, 21). It is a call to mutual contagion, to join a symbiotic chain (Mbembe 2024, 21) with plants and animals, minerals, the living and the dead, and the spirits that move among them.

Writing about my time in the exhibition and its performative public programme, [6] I tried to take that invitation seriously—to see if it could live on in writing. How may a visual or performative experience alter the way it’s later told, or shared remotely with those who come to it belatedly? (Sacchi 2013, 100–105). Can we meet somewhere in between? How may a page—this one, digital—become porous, shared, exposed? How may I, from my own training and the edges of the Italian academy, move beyond the habits of the argumentative text? These questions shaped what follows. The pauses, the gaps, the fragments and rewinds, the uneven syntax, the shifts in tone and layout—all small ways of working through what the exhibition left behind; attempts to resist the frontierization that divides, even within culture.

Reset & Play

In the curators’ words, Earthly Communities is a collective exhibition tracing the impact of European colonisation on the Indigenous territories of Abya Yala since the fifteenth century. Through practices and aesthetics drawn from the Americas and their diasporas, the works ask how human intervention has shaped—and scarred—the environment, confronting the colonial-extractivist idea of “nature” inherited from European modernity and searching for other ways of being with the non-human. All this unfolds from South Tyrol, a setting that seems, uncannily, to fit. [7]

A current of thought rooted in Indigenous worlds runs through the exhibition, unsettling its spaces, closing distances, undoing the vertical ways in which Western reason has long framed our relation to the land. Asked How do we abuse our earth?, the artists respond by opening other epistemic paths—ways of rethinking place, identity, life, subjectivity, agency. Voices, languages, and perspectives meet and graft into a moving structure, held together by two recurring tides that give it rhythm. The exhibition itself moves like the sea—swelling between the immanent beings and the practices of making—and it’s by following that rhythm that I find myself crossing the exhibition twice.

Many forms of life—or, within the narrow reach of an anthropocentric language, what we call the animate and the inanimate—share space. Once sidelined or branded as “resources” by European modernity, they appear here at Kunst Meran Merano Arte as independent presences, each with its own way of affecting and being affected. Shifting between the real and the representational, they disturb the human’s assigned centre—that white, self-assured point from which Europe has long looked at the world. [8] Animals, plants, seeds, minerals, fabrics, clay, water, the dead—even technological things—take part, as Mbembe writes, in a general community of beings (Mbembe, 2024, 49), of which the human is only one strand. Each carries its own way of relating, of exchanging energies and flows—active presences that touch and change us in return.

In the curators’ sequence, the first sketch of the living (Mbembe, 2024, 21) appears as a vast, violet prehistoric mollusc—two storeys high, woven collectively from rattan in the Maya tradition of hammock-making. At the centre of the exhibition, Sacred Waters, To Bloom () Florecimiento (2024) by Amanda Piña—a Mexican-Chilean artist and choreographer living in Vienna—gathers a constellation of coexisting beings. The mollusc holds a double resonance: it calls up water and the ocean, but also calcium, bone, the human form itself. In Indigenous and Afro-diasporic thought, water carries memory—a medium through which the violences and extractivist politics of colonial modernity are read. It bears the movement of oceans and currents—the AMOC [9] among them—but also the drift of migration, the Middle Passage, the forced crossings that shape our histories. Water is a living substance that joins unlike bodies: our bones and seashells made of the same salt, the same mineral breath. It threads together distant times, linking the Atlantic to ancient Tethys—the vanished sea that once was sealed to the east by the collision of the Adriatic plate with Europe, giving rise to the Mediterranean, the Alps, and the Apennines. The great Mollusc echoes this motion: a body in flux, a living system, an inhabitable chamber of resonance—as the video beneath it suggests [10] —a residual form composed of many lives.

In Flows Over Unities (2025), Luigi Coppola—artist, activist, and agronomist working from Puglia—treats the seed as more than a biological form: as a generative force, the starting point for an ecosystem of alliances. [11] Created in collaboration with BAU – Institute for Contemporary Art and Ecology, the work unsettles what we call “nature,” exposing it as a cultural and political construction, and gestures instead toward ways of living with the more-than-human—shifting the frame from extractive control to interspecies solidarity. At once aesthetic and agroecological, the seed becomes a kind of technology—a working form that looks toward what might yet come. It acts as a critical ground where two forces meet: the desertification born of a predatory relation to the earth, and emerging practices of shared care and cultivation. Taking its cue from South Tyrolean thinker and eco-activist Alexander Langer’s idea of the “evolutionary garden,” Flows Over Unities imagines a community that resists fixed identity—one in which parts shift and transform each other through temporary, living balance.

As you move clockwise, past the space shared by water, oceans, prehistoric molluscs, calcium, and seeds, new beings come into view, immanent forms that slip beyond human grasp, shaped by openness and scale. The paintings and ceramic sculptures by Samuel Sarmiento, a Venezuelan artist with roots in the Dutch Antilles, trace a speculative lineage of earthly life—forms that spill across the boundaries of classification. From within these complex bodies, faces, hair, limbs, and hands surface and recede, dissolving the systems that seek to name them and undoing the idea of the human as exception.

In Constellations. Le ciel aux yeux-racines (2021), Guadeloupean artist Minia Biabiany traces a movement from the ground to the sky—a gesture that is at once physical, symbolic, and speculative. Near the ceiling, panels of fabric suspend a new terrain: the grounded cosmogonies of Samuel Sarmiento drift upward into a celestial map that orients identities that are layered, shifting, and plural. The Pleiades—honoured by the Indigenous Kalina as living forces and cyclical agents—meet Afro-descendant cosmologies, stepping beyond the limits of Western astronomy to become figures of speculative world-making. Here, the constellation works as both poetic and political technology, reimagining the future from within the dense weave of Guadeloupe—or Caloucaéra, as it is known in Kalinago—and its diasporic worlds.

In Con te devolvo (returning) (2025), Sallisa Rosa performs a gesture of re-inscription—working with earth-matter as a living unity, in defiance of the extractivist logic that has long sought to master it. Shaped from Rio de Janeiro clay, [12] the small terracotta boat does not stand in for the world but acts within it—joining, for a while, the general community of beings that gathers in Merano, and quietly altering the space around it. Touched by a thick, foaming liquid and by the artist’s hands, the sculpture retains a porous kind of memory—one that soaks up what colonial erasure once took away. Clay is not inert; it holds what’s been lived, what’s been hurt. Canoe and caravel meet here as two technologies pulled apart: one tied to the earth, made for drifting and survival; the other born of conquest and extraction. Inside the clay, their tension doesn’t resolve—it opens instead a space for imagining new ways of living with the earth.

Further into the exhibition, the entanglements and the crossings grow more intricate. In Telling of the Stories, Paris-based artist Etienne de France enters into dialogue with Minia Biabiany through a two-channel video installation that pushes at the limits of historical knowledge, tracing alternative genealogies. Two stories inhabit the same room—overlapping in time, in place, in resonance. One unfolds in seventeenth-century Guadeloupe, in the aftermath of English raids on Martinique and Saint Vincent; the other in nineteenth-century Iceland, amid Jón Árnason’s gathering of folktales—Iceland’s own echo of the Brothers Grimm. A first-person voice [13] in Garifuna [14] drifts into a conversation between two men on a moor with a horse, their Icelandic words recalling the tale of a woman who once carved her story into stone. Across these layered timelines, [15] Biabiany’s Pleiades resonate with de France’s carved stones. Matter, again, acts as a poetic and political force—moving through history, unsettling its order, loosening what was once held in place.

At the top of the building, the invitation shifts again: to rethink our relation with what breathes, and what does not. Plants, strands of hair, insects, minerals, fibres, fruit, and roots draw us into exchanges that are material and felt—that speak, murmur, accuse. AGUA: From River Pulse to Canopy’s Breath (2025) brings together two long-running works—WATER: Encounters from 600 Movements (2019–2024) and Bromeliads – Among the Canopy’s Breath (2019–2025)—by Venezuelan artist Alexandra Gelis, who works between Colombia, Costa Rica, and Canada. Together they form a site-specific installation: an immersive, multisensory field in which plurality becomes both medium and material. Along the Vacilón River in Costa Rica, the forest’s relational existence endures through a kind of media spillover [16]—carried into the videos and textiles that Gelis has cultivated over decades of research. Grounded in an idea of gathering as a form of listening, the fabrics become living, recycled spaces—a compost that dissolves borders, weaving vegetal fibres with animal and human remnants. The work calls for a multisensory engagement that draws the viewer into a layered ecology of sounds, images, and scent—one that moves across disciplines and unsettles fixed identities, echoing the Peruvian anthropologist Marisol de la Cadena’s reflections on the coexistence of multiple epistemic and ontological worlds.

Peinar las raíces XII (2022) by Guatemalan artist Marilyn Boror Bor picks up threads of the previous work, advancing a form of affective, sensorial knowledge that holds two irreconcilable epistemic worlds in tension. Coloured Maya–Caqchikel textile strands are pressed into blocks of cement, a forced cohabitation that speaks of contraction—of air, of space, of ways of knowing—under the extractivist economies of global capitalist power. While the work’s materials lay bare the slow replacement of local economies and forms of subsistence, it is through touch that Peinar las raíces XII turns into a site of critique The fractures opened by the embedded threads act as gestures of resistance—small attempts at release that crack the cement’s solidity, revealing the possibility of another relational horizon: a breach through which, even under the pressure of compression, the memory, vitality, and regenerative power of ancestral knowledge continue to breathe.

Still alive (2025), by Berlin-based Colombian duo Mazenett Quiroga, unfolds within a post-internet constellation that rethinks identity through the very materials of the installation—fruit and vegetables in de-composition, [17] both everyday and excessive. Spread across a soft pink carpet, these organic forms assert their own subjectivity, their right to exist beyond the capitalist logics of utility and extraction, their pierced skins catching the light in quiet resistance. Released from the demand to serve human use, these forms persist as autonomous presences—desiring bodies [18] moving within their own cycles of decay and renewal. The piercings invert the logic of possession, opening a space to think of body and subjectivity through epistemologies of nearness and solidarity with life beyond the human. Other works by Mazenett Quiroga further unsettle the human impulse to draw a clean border between what lives and what does not. In Geophilia (2025), three stones—marked, tattooed, resting on stools before the glass door that opens to the outside—gather in quiet assembly. No longer cast as resources to be mined and used up, they stand as independent agents, indifferent to us, opening out into timescales that dwarf our own, inviting us to imagine community otherwise—wider, slower, more than human.

Overdub

Leaving the stones to their conversations, we pass through the glass doors and take our seats on the terrace of Kunst Meran Merano Arte, gathered around a white cylinder.

To Bloom () (2025)

Amanda Piña & Carolina Cifras

Kunst Meran Merano Arte (Meran, IT), 6:04 PM

Four trails of incense mark an invisible circle—a sensory map that orients the space and awakens its memory. At its centre, a low white platform holds a weave of orange and yellow rattan: vegetal matter carrying a lineage that reaches beyond Europe. Amanda Piña enters without a word, dressed in white. A T-shirt, printed in earthy browns, mirrors a fragment of ground. She lights the incense, traces the edges, removes the shirt. A gesture of yielding, of return—loosening the world’s image so that its matter might breathe again. Performer Carolina Cifras joins her—white clothes, a long braid. They meet, lift the rattan together. It quivers, catches the evening light, turns porous, alive. Under its glow, the bodies lose their edges, searching for each other, breathing in the same rhythm. The fabric magnifies it all: every vibration, every shade, every hesitation. It is also a solvent, softening difference, thinning the skin that divides. The two performers become a joint sculpture—a shared organism, a form in motion, a dynamic assemblage (Mbembe, 2024, 26). Their voices emerge as sound matter: distinct yet interdependent frequencies meeting in a single resonance. Beyond words, a vibration moves through body and space—the echo of a communication no longer bound to logos. Voice here no longer belongs to the individual but to the shared field that holds them, amplifying the sense of plural presence, of a breath held in common.

When one of them steps out from the fabric, the other remains still, wrapped in the light that slides across the platform. The sound lingers. The smoke thins. Then, slowly, the cloth falls—settling on the ground like the residue of a shared space-time. They embrace. They smile. Nothing is concluded: what remains is not the gesture itself, but the relation that made its form possible.

In the silence that follows, the fabric still emits its presence—a porous threshold between the human and the more-than-human, between body and matter. It holds another kind of time, immanent and slow, where sculpture becomes organism and movement turns into an act of sensitive cohabitation.

We return indoors, down a few steps, into a room that’s already moving.

Six Movements in a disobedient Garden (2025)

Alexandra Gelis & Adriana Ghimp

Kunst Meran Merano Arte (Meran, IT), 6:47 PM

Inside, the smell of plants lingers on the skin. Beside a projection that rises beyond human scale, multidisciplinary artist Adriana Ghimp builds a live soundscape of voices and presences—human and more-than-human, moving and still. Opposite, Alexandra Gelis’s long fuchsia hair carries the warmth of Cartagena, whispering memories of melting ice-cream cones on hot Caribbean afternoons. [19] The performer watches, listening—her stillness an invitation to do the same, eloquent in its quiet. Then she moves, drawing us into a soft vegetal embrace that awakens the space itself. On screen, plants multiply; insects flicker; colours and camera movements trace a subjective drift through the more-than-human. Six Movements in a Disobedient Garden unfolds as a sequence of chance episodes [20] in resonance, where the co-presence of many tongues—Italian, English, spoken, written, sung—, el nombrar en varios idiomas, stands as a declaration against semiocide, against the violence that destroys, with language, our memories, our places, our bonds.

The act of naming is a political gesture. Language splits open and stretches outward—becoming fabric, echo, matter. Voice—recorded, projected, embodied—becomes a vehicle for deeper listening, where words no longer order the world but move through it. Video, sound, and movement coexist as parts of a single audiovisual organism, until distinction itself begins to lose form.

The “disobedient garden” isn’t a place so much as a way of doing—a method of sensing and living together that unravels the colonial roots of how we name and know the vegetal world. Here, language itself grows wild: Italian, English, Spanish, Quechua, and Ladino twist together like roots in shared soil, carrying diasporic memories that refuse to be fully translated. As Gloria Anzaldúa reminds us, the crossing of a border—whether geographic or linguistic—is always a wound (Anzaldùa, 1987); yet in that wound, a new kinship can take hold. From the performers’ plural voices rises that fertile cut: a sound that heals even as it unsettles.

Each word, whether spoken or written, works like compost—mixing, breaking down, opening space for new life to grow. In Gelis’s hands, the audiovisual piece becomes an epistemic garden: a living system of translation between human and more-than-human, memory and matter. Images don’t describe, and words don’t explain; they vibrate, returning language to something vegetal—rhizomatic, wayward, alive.

From the first movement: An Exotic Garden Exotic: adjective.

Of foreign origin or character; not native. Introduced from abroad, but not fully naturalized, never fully acclimatized.

They are called exotic.

Never neutral.

Himalayan cedar – from the high Himalayas.

Olive tree—rooted in the Mediterranean.

Strawberry tree—red fruit of the Mediterranean.

Eucalyptus—traveler from Australia.

Bamboo—carried from Asia.

Magnolia—petals from East Asia, from the Americas.

Osmanthus fragrans—the sweet breath of China and Japan.

Chinese hemp palm – from central China.

Agave—the desert of Mexico.

Aloe—from southern Africa.

Opuntia, prickly pear—spines from the dalle Americas.

Lebanon cedar—anchored in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Sequoia—giant of California.

Redwood—the western United States.

Maples—from Asia, from the Americas, from Europe.

Camellias—flowering in Japan.

Cactus blooms—deserts of Mexico.

Lotus—from the waters of Asia.

Roses—cultivars crossing Asia and Europe.

Ornamental shrubs and beds—layered from many worlds.

A body in exile.

A body torn from soil.

Uporooted.

Roots adrift in water.

Carried across oceans.

Salt veins.

Exotic—a word that fixes them.

Exotic—a cage of syllables.

Always arriving.

Never belonging.

Never at home.

This garden—a human-designed archive.

An archive of silence.

Roots are maps.

Roots are scars.

Inmigrantes somos mapas.

Immigrants are maps.

I am maps.

I unfold in silence.

Leaves as witnesses.

Leaves remember.

Rustling exile.

We walk.

But the ground remembers.

A choreography of displacement.

Replanted dreams.

Cut. Replanted. Forced into harmony.

Harmony by scissors.

And yet—they resist.

Resistence in sap.

Their silence unsettles.

Silence as breath.

A beauty fractured by history.

A beauty charged with memory.

A beauty that reveals and conceals violence.

Petals conceal wounds.

Roots haunted by displacement.

A theatre of migration.

Roots as actors.

An archive of movement.

Movement as script.

An arrival without end.

Rewind

The performances To Bloom () by Amanda Piña with Carolina Cifras and Six Movements in a Disobedient Garden by Alexandra Gelis with Adriana Ghimp mark the crest of a oscillatory movement that curves back on itself. Walking back through the exhibition, what surfaces is a web of practices—artistic, artisanal, and agronomic—that, alongside living beings, trace a shared current running through the works.

In Still Alive, Mazenett Quiroga quietly unmakes the still-life tradition, shifting attention from depiction to presence. Their work frees vegetal matter from the melancholy of decay, allowing it to live on in its own right—a nature that recentres itself and gently pushes the human to the periphery. Samuel Sarmiento’s challenge to Western tradition takes a different route, working through technique rather than image. His ceramic practice—passed down orally—steps outside academic conventions to shape imagined genealogies, where matter itself acts as a vessel of memory and change.

Eliana Otta and Carolina Caycedo draw on the lineage of women’s textile and craft practices to rethink the grand narratives of rulers and heroic conquest, turning them instead into spaces of care, critique, and collective reimagining from below. An Imaged Friendship (a spiritual tambito) (2022) takes the form of a welcoming patchwork—a fabric of imagined correspondence spanning time and distance between the Chicana–Texan writer, poet, and feminist–queer thinker Gloria Anzaldúa and the Peruvian anthropologist and Quechua-language novelist José María Arguedas. The grand epics of tradition give way here to a form of collective storytelling—part reading, part writing. [21] The interplay of languages, of Anzaldúa’s and Arguedas’s distinct voices, becomes a practice of care and understanding, means of coexisting and thinking together. In Mineral Intensive Futures (2024), Colombian artist Carolina Caycedo looks to the World Bank’s 2020 report Minerals for Climate Action: The Mineral Intensity of the Clean Energy Transition, translating its technocratic language into a visual meditation on extraction and exhaustion—on a planet imagined purely as resource. At the centre of the tapestry, a vast pit exhales smoke and molten colour; along its edges, figures are crushed under the weight of gold bars, wind turbines, industrial machinery, buried pipelines, and gleaming high-tech cars.

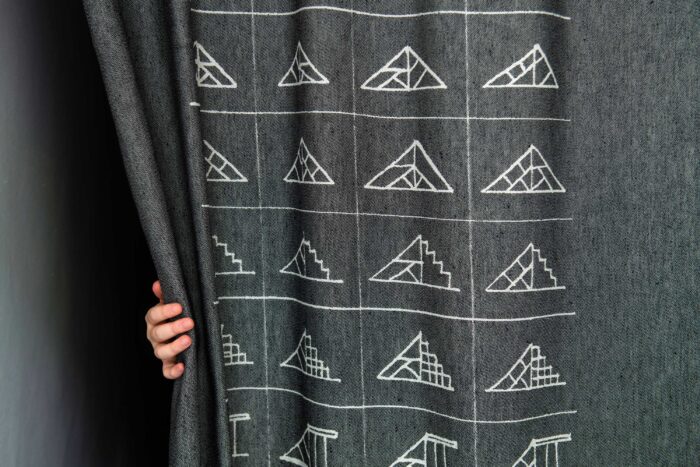

Working in close resonance, Marilyn Boror Bor and Amanda Piña carry the idea of collective “writing” into non-Western textile practices, where making becomes a way of thinking—local, embodied, and alive. Threads of colour course through Boror Bor’s concrete blocks like veins of memory—carrying the ancestral pulse of the Maya–Caqchikel weaving traditions of Guatemala’s Indigenous peoples. Piña weaves rattan—a tropical fibre once carried to Abya Yala by colonial trade—with the Maya craft of hammock-making, turning the act itself into a collective ritual of memory and repair. In both practices, the textile breathes as a form of living knowledge—a relational technology through which matter remembers, keeps, and transforms shared histories.

Luigi Coppola and Alexandra Gelis work at the edges where the human stops being the measure of things and nature becomes a counterpart. For Coppola, agroecology is a way to perform—collectively and politically—a new position in the world. For Gelis, gathering is a form of attentive listening, an emotional practice that follows the migrations, trajectories, and quiet resistances of plants. Both ground their research in Merano and South Tyrol, turning local rootedness into direct collaboration with the people who live there. Coppola brings together residents to experiment with the evolutionary populations method, cultivating new varieties of tomatoes, apples, and grains as adaptive forms of coexistence beyond extractive production models. Gelis, through exchanges with native-plant enthusiasts, yodel groups, botanist Thomas Wilhalm, anthropologist and linguist Johannes Ortner, and urban gardeners Anni Schwarz and Stefan Dosser, builds a sensorial archive of the territory—a non-extractive way of knowing that works to erode colonial taxonomies.

Echo

The public programme ends with a collective walk—an offering to the waters that gathers the threads of Amanda Piña and Alexandra Gelis’s work. They lead the way down the riverbed, scattering flowers that the current quickly takes. As the group moves through public space, the act of walking turns into a gesture of communion—a slow practice of knowing with the mountains that hold Merano. Through walking, a different kind of mapping takes shape: a relational geography drawn with the living body of nature, a body that listens and replies. In the final collective invocation, led by the workshop participants, we recognise matter’s vitality—its pulse, its capacity to connect—and give thanks for the exchange, for what has been given back.

Fade out

I close with the words of Achille Mbembe—words I returned to while taking part in the act of gratitude and restitution—so that the conclusion of this essay might coincide with yet another opening of The Earthly Community: “Nothing that has been lost needs to be given back. Some losses are not only incalculable but also irreparable. Yet the incalculable and the irreparable do not cancel or forbid the call for care and for truth—still less the call for justice. On the contrary, they only make that demand more urgent, more unending. In the end, they may well form the very ground of that infinite, unpayable debt on which every true community rests—every community beyond identity, the nation-state, and the contract” (Mbmebe, 2024, 7–8).

[1] Earthly Communities is the second chapter in The Invention of Europe. A tricontinental narrative (2024–2027), a three-year project by Lucrezia Cippitelli and Simone Frangi. Conceived as an act of unmaking, the programme loosens Europe’s singular self-image—exposing the debts, crossings, and genealogies that tie it to Africa, Latin America, and Asia.

[2] Achille Mbembe’s La communauté terrestre (2023) is not simply cited here, but reactivated—its title turned into a gesture of rewriting. The shift from singular to plural opens both a conceptual and political fault line, pushing the idea of community toward a relational horizon made of irreducible differences. Earthly Communities takes the plural as an epistemic stance: coexistence not as harmony or fusion, but as an ecology of situated relations—a terrain of frictions, affinities, and temporary alliances.

[3] Indigenous naming of Latin America in a decolonial key.

[4] The word community traces back to the Latin munus—a term that binds together gift and obligation, reciprocity and responsibility. Out of this ambivalence emerges the common: not a fixed or self-contained totality, but an open field of interdependence, continually renewed through the encounter with others.

[5] As Mbembe writes, this is “the organized violence that underpins both contemporary capitalism and our world order in general […] the process by which certain spaces are transformed into uncrossable places for certain population classes, who thereby undergo a process of racialization; places where speed must be disabled and the lives of a multitude of people adjudged undesirable are targeted for immobilization if not shattering” (Mbembe, 2024, 137). It exposes a planetary order split into unequal regimes of mobility, structured by profit and extractivist logic—a world divided between bodies made insurable and those left exposed.

[6] The exhibition extended beyond the gallery through a public programme of film and performance. Screenings included Jiiblie (2020) and Journey to a Land Otherwise Known (2012) by Laura Huertas Millán, and Dung Kingship (2024) together with Opossum Resilience (2019) by Naomi Rincón-Gallardo. The programme also featured the two performances discussed here: Plants and Resistance (2025) by Alexandra Gelis and To Bloom () (2025) by Amanda Piña.

[7] South Tyrol—a region of many languages and deep historical strata—mirrors the wider tensions of the present within a local frame. History, economy, and politics fold into one another here, shaping both landscape and identity. From this terrain, the exhibition opens an inquiry into the entanglements of social and environmental justice, re-awakening agricultural knowledges and soil-care practices that imagine other ways of living with the environment. In this light, South Tyrol stands as an emblematic case: a vantage point for rethinking sustainable land relations and the interdependence of human and more-than-human worlds.

[8] Achille Mbembe describes a world split between lives allowed to matter and bodies left unprotected: “For not all bodies are viewed as containing life. Not each life and every breath has supreme value. Discounted bodies are dismissed as lifeless. […] The kind of life they bear or contain is not insured, or is uninsurable, enclosed as it is in extreme and thin envelopes.” (Mbembe, 2024, 140).

[9] The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation—or AMOC—is a vast conveyor of currents moving warm, saline water north from the tropics and drawing cold, dense water back south through the deep. Acting as a planetary regulator, it links ocean and atmosphere in a delicate equilibrium that keeps Europe far warmer than latitude alone would allow.

[10] Shot from above, the video follows a cluster of performers moving inside a woven rattan structure. Bodies knot and drift, brushing past one another before blurring into a single, slow breath of motion. The image hovers in suspension—almost virtual—as if what we see were a living organism caught mid-transformation.

[11] From his base in Salento, Luigi Coppola turns the Apulian landscape into a site of critical experimentation—where ancient olive trees, heirloom seeds, and community mills operate as tools of resistance to desertification and extractivist economies. His practice unsettles epistemicide by reanimating agronomic and communal knowledges as acts of collective intelligence and shared care.

[12] During the guided walk organised as part of the performative public programme (21.09.25), Lucrezia Cippitelli and Simone Frangi told the audience about an episode from Sallisa Rosa’s process—her failed attempt to work with Amsterdam’s soil, dismissed there as lifeless earth.

[13] Set in the sixteenth century, the story follows the escape of a Kalinago woman—a member of the Indigenous people of the Lesser Antilles—fleeing the violence of European colonisation. Guided by a map carved into rock and overgrown with moss, she moves toward a cluster of legendary volcanic islands.

[14] Spoken in parts of Central America, the language emerged from the meeting of enslaved African and Indigenous Caribbean speech.

[15] Inspired by an imagined story shared between Icelandic poet Thor Vilhjálmsson and Édouard Glissant, the work conjures a landscape of speaking stones and burning moss—mineral and vegetal lives giving voice to a world in flux.

[16] Biologist David Quammen describes it as the process by which an organism moves—or accidentally finds itself—within an alien environment.

[17] The word de-composition holds a double charge: it refers at once to the biological process of decay and to a refusal of traditional pictorial composition. Here, it becomes a gesture of conceptual and formal undoing—an unmaking that frees the image from order, allowing matter to recover its own pulse and capacity to act.

[18] The work draws attention to the latent eroticism that fruit and vegetables have acquired in digital culture—standing in for the human body, eroticised through the codes of sexting and online intimacy. In Still Alive, these crops become post-digital bodies, caught in tension between nature and artifice, the biological and the technological. The piercings act as marks of hybridity—tactile points where the organic meets the mediated—turning vegetal matter into an erotic, communicative subject.

[19] At breakfast in Venice, Alexandra Gelis mentions that the fuchsia in her hair traces back to a childhood memory—the colour of raspao, a street drink of crushed ice, syrup, and condensed milk that cuts through the heat of Cartagena. “It’s a memory of the Caribbean, where I’m from», she says. “It gives me strength.” A small act of remembrance that ties body, place, and artistic practice—and runs through her Raspao series.

[20] I. An Exotic Garden, Un Giardino Esotico, Ein Exotischer Garten; II. A Graften Union, Un’Unione Innestata, Eine Veredelte Verbindung; III. An Underground Chorus, Un Coro Sotterraneo, Ein Unterirdischer Chor; IV. A Herbarium of Possibilites, Un Erbario di Possibilità, Din Herbarium deiìr Möglichkeiten; V. An Alpine Resistance, Una Resistenza Alpina, Ein Alpen-Widerstand; VI. A Pluriverse in Bloom, Un Pluriverso in Fiore, Ein Blühendes Pluriversum.

[21] The fabric stretches out across the floor, unfolding into a place to pause, to read, to linger. Visitors sit directly on it, leafing through the books the artist has left behind—a quiet gesture that brings the work close, turning it into surface, archive, and collective reflection all at once.

Bibliography

Anzaldùa, G. (1987). Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. Aunt Lutte Book Company.

Mbembe, A. (2016). Critica della ragione negra. Ibis. Original work published Critique de la raison nègre. La Découverte.

Mbembe, A. (2024). La comunità della Terra. Marietti 1820. Original work published La communauté terrestre, La Découverte.

Sacchi, A. (2013) Oltre la nostalgia: spettatori ritardatari e performance storiche. S. Tomassini, D. Giuliano (Eds.), Biennale Danza 2013. Abitare il mondo, trasmissione e pratiche, La Biennale di Venezia, 100-105.