Artificial Soundscapes and Landscapes

On Foley artists, perception and imagination between artifice and reality

Sound, perception and imagination are essential ingredients in the research and practice developed by Finnish artist Jonna Kina, who presented her first solo exhibition in Italy last September. Curated by Manuela Pacella, the exhibition Objects and Sounds at Pastificio Cerere Foundation in Rome gathers a group of works realized by the artist between 2013 and 2017, inspired by some considerations on the Foley artists and their job.

When I think of Nordic landscapes, in my mind I always depict extensive open grounds covered in white, quiet under the snow blanket that softens any noise. When I’m away from home for longer periods and I happen to think of my city, Rome, one of the first images that comes to my mind in distance is the traffic jam (no sentimentality here): a chaos of cars, badly aligned into crooked rows in the streets of the city’s suburbs, engines roaring and horns yelling. These kinds of mental pictures—both personal memories or views built through external suggestions—are always accompanied in my consciousness by the presence of a soundtrack.

Jonna Kina, Somnivm, 2018. Installation view, Beaconsfield gallery, London

As explained by Raymond Murray Schafer in his book The Tuning of the World, hearing was the predominant sense at the origin of human history, way more effective than sight. With the passing of centuries, the eye slowly came to ruthlessly replace the ear as the main source of information in our daily life. Sight is a despotic sense, well supported by media politics and new technologies, so that sometimes we forget how hearing plays a central role in our being in the world, as well as in the process by which we perceive the environment that surrounds us, to then reassemble it in our mind.

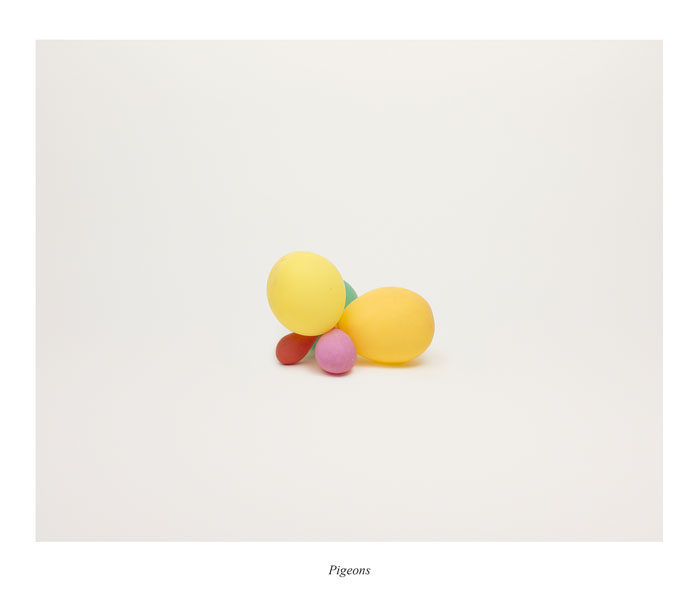

Jonna Kina, Foley Objects, 2013, archival pigment ink print.

Not many are aware of the fact that cinematographic sound is the result of a meticulous work of reconstruction, mainly taking place in post-production. Usually, only the voices of the actors are recorded during the shooting, meaning that any other sounds and noises need to be artificially added later. Foley artists are heroes in this procedure. Named after Jack Donovan Foley, pioneer of many sound effect techniques at the end of the Twenties, these professionals make use of the most improbable objects and methods to recreate soundscapes able to be as real and engaging as possible to our perception. Magically the noise of a letter pulled out from its envelope becomes a spaceship door; tinfoil can be used for fire; a pineapple peel sounds as a dinosaur skin and so on.

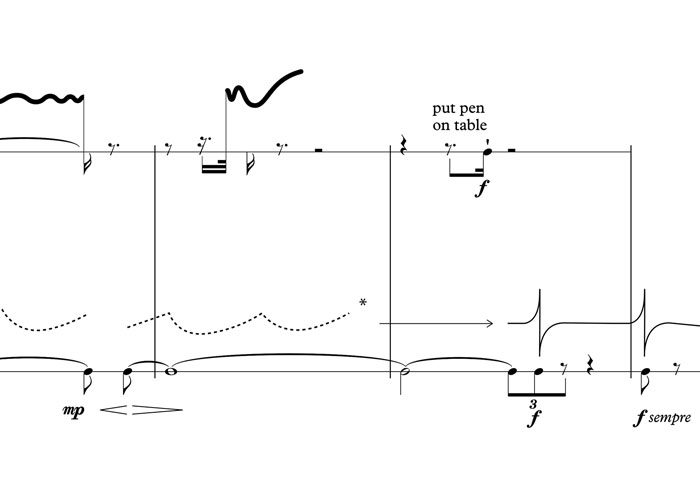

In 2013, artist Jonna Kina realized a series of photographs titled Foley Objects, portraying some of the objects used by Foley artists to compose a visual archive of sounds. Indeed, each image of the series is matched with a short caption describing the desired sound effect. Four years later, the Finnish artist accomplished a video work on this same subject titled Arr. for a Scene, where two Foley artists are filmed while adding sound to the famous shower scene of the movie Psycho by Alfred Hitchcock. With the collaboration of composer Lauri Supponen, Kina has later translated their gestures and noises into the language of music, creating a score that takes inspiration from the work and research of experimental composers and musicians such as Cornelius Cardew and John Cage. The triptych of prints Score of Arr. for a Scene opens the itinerary of the exhibition, creating a circular route. The visitor will have to go through the same room, after having watched the video and before exiting the show.

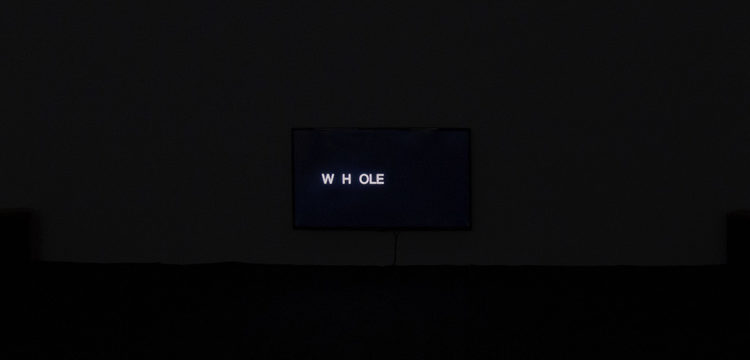

Jonna Kina, Arr. for a Scene, 2018. Installation view, Sounds and Objects, Fondazione Pastificio Cerere, Rome.

By unveiling and deconstructing forms and methods of cinematographic sounds, Jonna Kina’s works suggest complex questions dealing with a diverse range of topics: the trans-sensory power of sound; human perception and its processes; the relations and exchanges between artifice and reality; the mechanisms of symbolization and translation from one language to another; the relationship between the viewer and the artwork. The artist adopts an analytical attitude without losing her imaginative gaze, and opens a window on the patterns and the functioning of the joints structuring our consciousness and imagery, intended as a result of an ongoing process of negotiation between the outside world and our inner self.

After visiting the exhibition, I had the chance to open a conversation with Kina, and go deeper into some aspects of her artistic research, starting from the works I saw at Pastificio Cerere Foundation.

Jonna Kina, detail of Score of Arr. for a Scene, 2017. Archival pigment ink print.

Marta Federici: Foley artists are a good example of the kind of workers who act behind the scenes, invisible and mostly unknown. I’m pretty sure that even people who have an idea of film post-production processes are not always aware of how these ingenious artists physically produce the sounds they collect in their archives or record for a specific work. How did you happen to meet them, and how did your interest in their work arise? Were they immediately available and open to collaboration?

Jonna Kina: My interest towards Foley effects started when I was working with a sound designer on my film Reconstructions (2012). I was being a Foley artist myself and that got me thinking about how this is a fantastic behind-the-scenes structure of so many great stories in film history. Thinking through Foley artists’ profession can somehow at the same time break and support the whole storytelling phenomenon.

As often, one thing leads to another; in the very beginning of my research on Foley Objects, I contacted several Foley artists and sound designers. I wanted to physically see and hear how they are doing their magic. These artists deepened my understanding of the art and were very kindly willing to participate in my project, and I eventually ended up spending a lot of time with them.

Jonna Kina, Foley Objects, 2013, archival pigment ink print.

When I came to visit the exhibition you explained to me that sound is a fundamental component of your research. The first work inspired by Foley artists you created is a series of photos, Foley Objects (2013) portraying some of the objects they use. By associating a caption that describes the sound effect sought by Foley artists to each image, you trigger a sensorial short circuit in the viewer, which involves both sight and hearing in the reception of the work. Can you tell me more about your relationship with sound? What does it mean for you to investigate the sound dimension through other media and languages?

I like to think that sound is not a distinct element, but rather an inseparable part of a complexity. I find it interesting to conceptualize and manipulate sound, and to think how to perceive it through other media such as words and images, like I have done in Foley Objects. In that series the everyday objects were carefully chosen with a surreal logic between the photographed object and the description of the sound. For example, a plastic bag full of basswood seeds sounds like waves on a shore, a cable tie sounds like wind, and aluminium foil sounds like the warmth and energy of fire.

My works are often conceptual and structural in terms of method, which also directs the use of sound in my work. Sound has special metamorphic quality. I am fascinated about the imaginary aspect as well, for example to imagine the sound without being able to hear it. Sound and music are something very direct, deep and instantaneous. Something that moves and expands in all dimensions.

Jonna Kina, Foley Objects, 2013, archival pigment ink print.

After the Foley Objects series in 2013, you realized a second work in 2017, the film Arr. For A Scene. How did your research on Foley artists and your relationship with them evolve over that timespan? How did the decision to make a video emerge?

The idea of making a film emerged already when I was working on the Foley Objects series. I made a research and worked closely with several Foley artists both in Finland and France. I had the opportunity to follow their work closely while they were re-enacting and recording sounds in the studio. I also had a chance to follow some workshops and visit several different studios, which helped me to compose the final work. This collaboration with different Foley artists was very crucial to me. In Arr. for a Scene, I worked with French Foley artists Élodie Fiat and Gilles Marsalet, during my Cité Internationale des Arts residency in Paris. We rehearsed and planned the choreography together in my tiny studio apartment. There was something that reminded me of the movements of a contemporary dance piece, but also of a musical performance; that was the direction I tried to keep in the film. Therefore, Cage’s Water Walk (1959) was an important reference to my film. I also wanted the title of the film to refer to a musical composition: “Arr.” is a shortened version of “arrangement.” After finalizing the film I worked with composer Lauri Supponen with whom I created a full score of Foley sounds. Through notation methods, I was able to explore sound’s structures and forms while transforming cinema into a musical and compositional language.

Jonna Kina, Arr. for a Scene, 2017. 5’18”, 35 mm film transferred to 4K/HD, color, sound.

In the video you have adopted a frontal framing. The screen with the shower scene from Psycho which Foley artists are looking at is not visible, as it coincides with the camera’s positioning. This way, a face-to-face interaction is established between the viewer and the two Foley artists, who apparently look into the camera. One has to recognize the scene of the movie through sound, to understand what is happening. Other works you made also demand for an active involvement of the viewer. For example, the Foley Objects photos are “completed” only when who is looking at them reproduces the sound of the object in the picture. A work not included in the show, Notes from the other side (2013-2015) collects a series of short notes written on the back sides of photographs from private albums. You took pictures of the annotations, but not of the related photos: again it’s the viewer that must contextualize the sentences, trying to imagine what kind of image they refer to. Can you explain the role of perception and imagination in your works? And also, how does the relationship with the viewer influence your artistic research?

In the Arr. for a Scene the position of the camera and the fact that the performers were looking straight to the viewer became essential. With my cinematographer Ville Piippo, we carefully positioned the screen next to the lens in order to create this double perception. The idea was to achieve a sort of “reversed cinema” where the viewer becomes an active part of the scene or is the scene itself.

In the series Notes from the Other Side (2013-2015), I collected images from private albums that ended up in flea markets. I started the project when I was living in the United States. There were such sentences as, good boobs you got there kid, extra pictures to give away, my family, the house where I used to live, keep this and send this one back. The hand written notes carry more meaning without the referred photographs.

The perception and imagination of both the subjective and the objective realm plays a great role in my work. I often find it necessary to reinvent new methods of organizing, discovering, constructing and deconstructing the material around the work. I also like the idea of the viewer taking part in the process of conceptual circular approach: recycling and reusing, as opposed to disposable exploitation. Objects looks back at you. They have a life of their own.

Jonna Kina, Somnivm, 2018. Installation view, Beaconsfield gallery, London.

You told me that when you first heard about Foley effects and that most of the sounds are created artificially in post-production, you had a rejective reaction, as if Foley artists were deceiving people with their unexpected gimmicks! Indeed, the works in the exhibition make the ambiguous nature of our relationship with what is fake and what is true evident. Even when we discover the unreliable source of the noises produced by Foley artists, those noises still remain tangible and real to our perception. This made me realize the incredible imaginative power of sound, but also made me think of the condition defined “suspension of disbelief,” that is our mental state when we watch a film or read fiction: in order to enjoy the story, we consciously decide to accept what we face as true, no matter how fake it looks. In another film you shot in the marble quarries of Carrara a year ago, Somnivm, you manipulated the footage removing almost all the evidence of human activities at the site; the result is a fake documentation. How artifice and reality interact in your work and research?

The aim to achieve a pure documentation of reality has scientific benefits but can leave out something fundamentally relevant. For me, it is more important to trigger a dialogue and open structures, or to create a situation that allow us to participate in the making of reality with the whole sensory system.

Carrara marble and the 35mm film material itself are both the subject and medium of Somnivm (2018). Somnivm was stimulated by a historical relationship between the marble industry and anarchism. This small fiction-making or manipulation in the post-production turned into a transformative act. It takes Somnivm far beyond the realm of documentation. For me, this kind of artifice can actually reveal something more. Sometimes hiding can reveal the structures better. Also the process of participation, adaptation and discovery gives an active role to the spectator. I often give restrictions or limitations to myself, which can be exciting but also forces me to always consider new approaches. Sometimes material or form can already steer the process to a certain direction, such as using 35 mm film.

Jonna Kina, Akiya, 2019. 35mm film transferred to 4K, 4″51′, color, sound.

Sound has an important role also in your last work, Akiya, 2019, in which a reel-to-reel tape recorder plays a song that tells a contemporary story, that of the increasing number of abandoned houses and buildings in Japan, in the ancient style of traditional Japanese Nō musical drama. Will you continue to work on sound?

In my latest film work Akiya, I have actually been working with human voice and a singer. Language, urbanization and storytelling play a great part in this work. It is also about connecting words to a metaphysical reality. It stands at the threshold of fiction and documentation. On the other side, this work could be considered as both a poem and a choreography for a machine. I can see many possibilities to continue my upcoming research through sound. I want to keep my relationship to it very open and humble, as Rilke says, “to start afresh—to be a beginner.”