A Brief History of Invisibility

On the production of an imaginary in absence, reflecting on the political potential to inhabit invisibility

Curated by Lucrezia Calabrò Visconti in collaboration with collective ALMARE, Get Rid of Yourself (Ancora Ancora Ancora) is a collective sound exhibition that takes shape in the dark. Conceived for and in the space of Fondazione Baruchello, the project investigates the production of imagery in the absence of sight, to reflect on the political possibilities of inhabiting invisibility. Disseminated along a sound path built in collaboration with the ALMARE collective, the artists’ narratives act in the dark, transforming a privative condition into a place for the active sharing of practices. Here, the critical essay accompanying the exhibition by curator Lucrezia Calabrò Visconti, followed by a methodological note by ALMARE.

Get Rid of Yourself (Ancora Ancora Ancora) gets its title from the audio-essay Get Rid of Yourself, Again by Radna Rumping (2017), borrowed in turn from the ciné-tract Get Rid of Yourself by Bernadette Corporation (2003). This third repetition of the title proposes to use the expression “get rid of yourself” as an emergency mantra, a speculative aid-platform available for anyone who would feel the impelling urgency to get rid of themselves. If the “the investigation of the past is nothing but the shadow cast by an interrogation directed at the present,” the issue we pose to contemporaneity today casts its shadow on a series of past stories, that I thought worthy to briefly tell.

Dafne Boggeri, 149 anni luce dalla Terra, 2008

Get Rid of Yourself, 2001

Twenty years have passed since 2001, when the multiple-identity collective that goes under the pseudonym Bernadette Corporation, back then based in New York and Paris, began to work on Get Rid of Yourself, an “anti-documentary” focusing on the controversial strategies adopted by the Black Blocs, mainly settled in the context of Genoa’s G8 events that took place in the same year. In order to finish the movie, Bernadette Corporation started a collaboration with the post-situationist activists’ division Parti Imaginaire, which the better known collective Tiqqun [1] was part of. The meeting of these fluid entities gave birth to what was meant to be, according to Bernadette Corporation’s definition, the adaptation of a ciné-tract, a format invented during the students and workers’ upheaval in May 1968 in Paris.

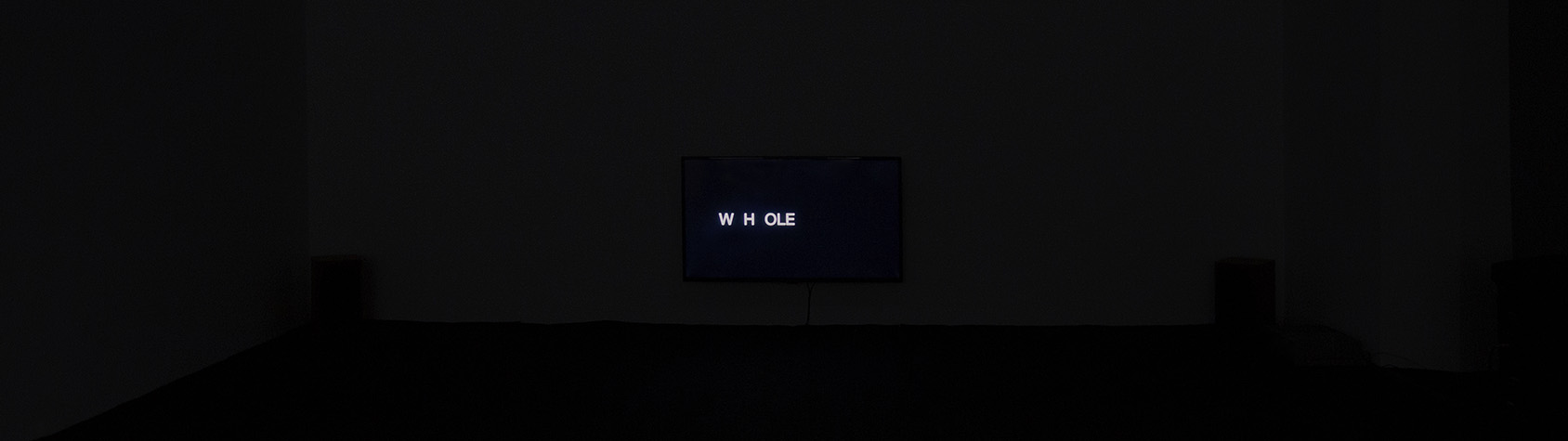

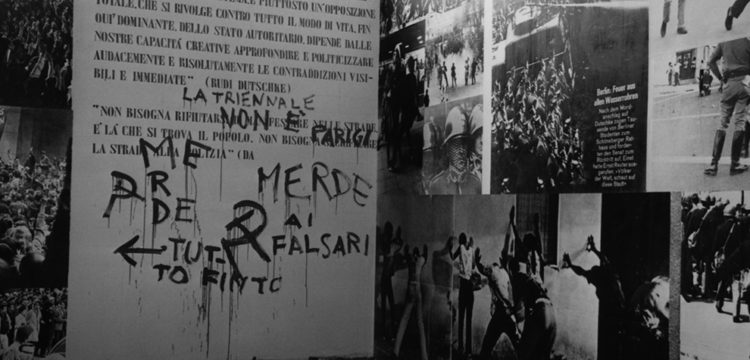

Bernadette Corporation, Get Rid of Yourself, 2001-2003. Educational materials, installation view, Fondazione Baruchello, Rome. Photo Alessia Calzecchi.

The experience of the ciné-tract, that very rapidly turned into a failure already in the summer of 1968, foresaw the production of short silent 16mm films, strictly linked to the militancy of those years. Filmed by experimental filmmakers, among which Chris Marker, Jean-Luc Godard and Alain Resnais, the ciné-tract were officially distributed as anonymous documents, and remain as the legacy of a momentum in the history of the French Left particularly connected to the cinema engagé. Nonetheless, the kind of experimentation Bernadette Corporation was interested in dealt with the idea that the ciné-tract wouldn’t have educational purposes in regards to the political situation in which they were created. These documents would rather be destined to a specific community, and meant to accompany that same political situation, with no need for further explanation. From here, the attempt to reaffirm such a specific format in a contemporaneity quite refractory towards this shared collective clarity of intents, but anyway united in the protest against what the events happened during the G8 Summit came to signify.

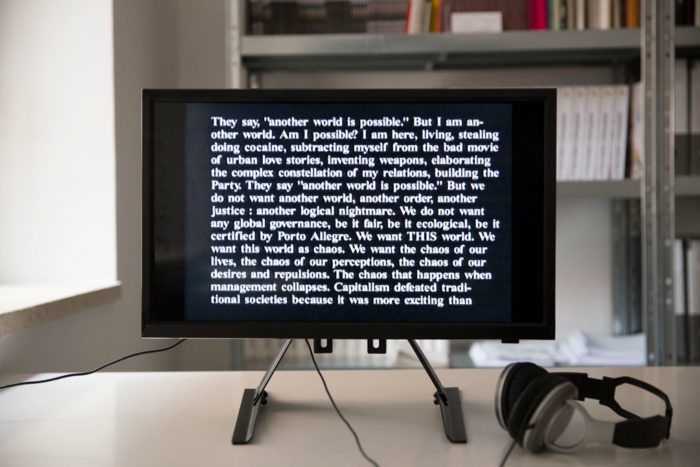

Get Rid of Yourself bears direct witness to the summer 2001 Genoa riots, juxtaposing them to scenes filmed in a quiet beach in Calabria, where the collective retired a few days after the protest, alternated with some posthumous footage in a flat in New York where the independent cinema icon Chloë Sevigny tries to reinterpret by heart the Black Blocs quotes recorded during the shooting, often failing and numbing their political density. In the movie, the actions and the words of the anarchist activist group self-identified as Black Blocs are used as a narrative device and some sort of case study, a concrete example of the potential that can be produced by a community based on the shared radical refusal of a political identity—or, better to say, the refusal of an identity tout-court. Despite not taking a clear position on the film’s unnamed protagonists and on their symbolic yet violent actions (destruction of cash machines and banks, supermarket looting, construction of barricades to be set on fire), Bernadette Corporation seems to sympathize with anti-institutional eversive strategies at large, used by Black Blocs to create “offensive zones of opacity”—as strategies that can be defined in ideological continuity with the very same artistic practice of the collective.

Bernadette Corporation, Get Rid of Yourself, 2001-2003. Educational materials, installation view, Fondazione Baruchello, Rome. Photo Alessia Calzecchi.

The documentary seals the tensions of the epoch in which it was produced, in regards to the possibilities offered by the conscious choice to live invisibility, where the act of “getting rid of oneself” was situated on the one hand within the disenchantment towards institutional politics’ protocols, conniving to neoliberal dynamics, and on the other hand on the realization of the inefficiency of traditional militancy strategies. Through the figure of the Black Bloc, Bernadette Corporation removed itself from a culture that had delivered the issue of subjectivity directly in the hands of the capital.

The matter of disidentification as a strategic choice, opposed to neoliberal dynamics of control, rises way before than Get Rid of Yourself, instigated by the full-blown “death of the author” as diagnosed by Roland Barthes and shortly after certified by Michel Foucault at the end of the 60s. Despite the divergence between the two philosophers’ positions, they both agreed on one point, that is to say the observation that the mythologized conception of the author would be born with bourgeois modernity, inherent to capitalist ideology’s individualism.

Bernadette Corporation, Get Rid of Yourself, 2001-2003. Educational materials, installation view, Fondazione Baruchello, Rome. Photo Alessia Calzecchi.

Starting from this revelation, many will identify in collective writing an antagonistic practice to capitalist society and its congenital cultural industry—from historical avant-garde, through the ciné-tract experience, to Bernadette Corporation itself and the Invisible Committee, via the Italian case of Wu Ming, to get to many other historic and contemporary authors who will openly claim their anonymity or sign with multiple names. Collective writing becomes a way to free writing itself from the subject, both in philosophical and economical as well as legal and penal terms, by having identified within visibility—and, consequently, identifiability—the main instrument of uptake in the spiral of commodification, inasmuch as the primary weapon for authoritarian control. It is no coincidence that in Introduction on Civil War Foucault is quoted by Tiqqun: “As power becomes more anonymous and more functional, those on whom it is exercised tend to be more strongly individualized.”[2]

The practice of disidentification has its roots in the belief that the repressive power of the State is not directed towards the elimination of the revolutionary subject, but rather toward a strategic process of incrementation of its visibility, necessary for its consequent demonization. [3] From here the proposal of invisibility, chaos and noise as emancipatory spaces. This seems to echo the metaphor proposed by Fred Moten and Stefano Haney in Undercommons (2013), when they speak of the necessity to refuse the idea that music starts only when the musician takes up their instrument. In some sort of subversive revival of Cage 4’33’’, Harney and Moten insist indeed on the necessity to listen to the existing noise we are already producing, to embrace that noise and to resist the temptation to turn it into music.

Mina, Ancora Ancora Ancora, 1978. Educational materials, installation view, Fondazione Baruchello, Rome. Photo Alessia Calzecchi.

Ancora Ancora Ancora, 1978

On August 23rd, 1978 the face of Italian singer Mina was recorded in the images of Ancora Ancora Ancora [again and again and again], a video shot during a concert at Bussoladomani in Marina di Pietrasanta, where she had performed for the very first time twenty years before. Mina chose at the last moment to use this video as the closing theme song for the TV program Mille e una luce [A thousand and one lights], instead of the long-awaited new version of Città Vuota [4]. Nonetheless, the integral video was broadcasted only once: since the second episode, the video was censored for the presumed excessive sensuality of its images—a close-up on Mina’s face, framing her lips as she sings [5].

In September, the same year, Mina announced her professional farewell: for the following twenty three years the “Tiger of Cremona” refused all the offers to appear in public and on television, although still recording and releasing music from her private studio. The singer abdicated her image, fixed without any warning for the very last time in those scandalous images of Ancora Ancora Ancora. Since that moment Mina became to the world only and exclusively a voice, a voice that never revealed the reasons for her choice.

Meanwhile, a transition was taking place in Italy, toward what will be defined as “riflusso” [reflux] meaning the retreat to the private sphere characterizing the end of the 70s and the beginning of the 80s in Italy, marking the definitive conclusion of the revolt season of the ’77 Movement. “Riflusso” literally refers to the flowing back of the water, after the wave has hit the shore: “the wave was the long one of the ’68, that in Italy generated a decade of movements. Just like after a swell, that leaves behind seaweed, scraps and dead fish all over the sand, also the wave that at that time, for better or worse, shook Italian society, left a bit of everything behind.” If the Movement had picked instances of the student and worker movements, of forms of feminism, of the traditional parties’ contestation, and—generally speaking—of the active and organized refusal towards neoliberal forms of consumption, the end of the decade had witnessed the Movement’s most radical fringes get to the most violent ends, especially with the rising of autonomous armed groups.

The summer of 1978 was the summer of the search for Aldo Moro’s murderers, the summer of “diffused terrorism” (counting more than thirty terror attacks only by the beginning of July), but also the summer of Saturday Night Fever, with the return of the shopping season, and the recovery of an hedonism that will lead to the so-called “Milano da bere” [Milano to drink] season. It’s the year of concerts in stadiums, even though, as Mina’s one at La Bussola, with strict police surveillance, carabinieri at the entrance and undercover police among the audience.

When Get Rid of Yourself comes to life, twenty years after, it evokes this transition period in its incipit: “TWENTY YEARS. Twenty years of counter-revolution. Of preventive counter-revolution. In Italy. And elsewhere. Twenty years of sleep under the eyes of security guards behind security gates, guards. A sleep of bodies, imposed by curfew. Twenty years. The past does not pass. Because war continues. Circulates. Extends. A new calibration of subjectivities. In a new superficial peace. An armed peace well made to cover the course of an imperceptible civil war. Twenty years, there was punk, the movement of ‘77, Autonomy, the city Indians, an eruption, a whole counter-world of subjectivities that no longer wanted to consume, that no longer wanted to produce, that no longer even wanted to be subjectivities. The revolution was molecular, the counter-revolution was also molecular.”

Radna Rumping, Get Rid of Yourself, Again, 2018, 39′. Installation view, Fondazione Baruchello, Rome. Photo Alessia Calzecchi.

The “molecularization of the counter-revolution” is a biopolitical process, acting still today on contemporaneity, actually in larger and larger doses. The forms of power traversing us have become more and more ubiquitous, light and decentralized: their method intends to infiltrate the daily life texture, in such a capillary way so to become imperceptible, apparently invisible. The most immediate consequence of this process is translated in the progressive increase of the distance from the individual experience and the intangible power dynamics that determines it. As a lapidary Franco Bifo Berardi states “(I)n 1977, human history reached a turning point. Heroes died, or, more accurately, they disappeared. They were not killed by the foes of heroism, but were transferred to another dimension, dissolved, transformed into ghosts. The human race, misled by burlesque heroes made of deceptive electromagnetic substances, lost faith in the reality of life, and started believing only in the infinite proliferation of images.”

Teresa Cos, Archive of Loops, 2017-2019, ∞. Installation view, Fondazione Baruchello, Rome. Photo Alessia Calzecchi.

During the past twenty years, the weapons of this process of abstraction have merged in numerous biopolitical techniques of governance, among which the financialization of contemporary life, the development of an economy of presence, and the invention of the (bureaucratic, financial, digital) protocol. In the period between the 90s and 00s, since the so-called new economy has converted the arbiters of conventional value linked to the production of commodities to immaterial alternatives such as experiences and emotions, physical proximity—immediate and in the flesh—has been capitalized as one of the possible options ahead of the various shades between absence and presence offered by the use of new technologies in our daily transactions.

However, rather than articulating a range of emancipatory solutions regarding our activities, this mechanism had sided the urgency of the hyper-productivity typical of the “libidinal society,” which has incorporated every realm of our lives through the multiple platforms we use to mediate ourselves with the world, making the distinction between work, rest and leisure time impossible. So it happened that the functioning of the institutional apparatuses began to base itself upon our necessity—and will—to be always present: the so-called “fear of missing out” syndrome, to mention Felix Stalder, brings “everyone to voluntarily do what no-one actually would like to do.” [6] Differently from the conventional legislative forms imposed by the governments, depending on the legitimacy and consensus of the subjects in power, the protocols ruling our hyper-presence are set in motion by the voluntary adoption, for instance, of “terms and conditions” we accept before reading, trading our privacy to access a promise of attention, legitimacy or simply dialogue with the other.

Dafne Boggeri, Starting the rhythm, 2019, 1’47”. Installation view, Fondazione Baruchello, Rome. Photo Alessia Calzecchi.

Get Rid of Yourself, Ancora Ancora Ancora, 2019

As suggested by Bernadette Corporation, in this dystopian horizon of activity the traditional forms of opposition have ceased to be effective: in a economy-of-presence regime, the praxis of the strike as physical absence is surely no longer a plausible strategy of refusal, as well as the image of the protest par excellence, namely the balaclava that goes from Toni Negri’s [7] famous eulogy to Carlo Giuliani’s one, covered in blood on Genoa asphalt, seems by the least an anachronistic precaution, compared to the pervasiveness of a power system in which the concept of visibility is more and more distant from the concept of the visual. In fact, despite being equipped with a growing variety of optical media, we are also more and more incapable of grasping the algorithmic totality around us, since the primary expressive modalities of the protocols, the algorithms and data ruling our existence, are not compatible with our human conception of the visual. “Visibility is degraded visuality” Sven Lütticken states when analyzing the attempt – which seems sometimes obsolete today—by the institutional critique of the 60s and 70s, to shorten the distance between the two notions: “in rejecting modernist notions of visuality (the abstract image as pure form, as opticality), institutional critique has in fact refocused on visibility: making visible the activities of sponsors, the institution’s implication in the wider political economy and the ruling ideology and so on. (…) visibility becomes the new visuality; that is, the articulation of hidden structures and networks in forms that merge the starkness and bluntness of visibility with the complexity of the visual.” One could say that institutional critique attempted to move in that medial space which in the language of digital technologies would be defined as “interface,” reappropriating a dispositive today completely subsumed by the technique of governance of the protocol, and thus has become uncontrollable from our position of simple “users.”

Erica van Loon, Your Brain Has No Smell, 2017/2019 35′. Installation view, Fondazione Baruchello, Rome. Photo Alessia Calzecchi.

In the audio-essay Get Rid of Yourself, Again, Radna Rumping declares “the title of BC’s film has become even more seductive than it already was. A state of becoming slippery feels harder to accomplish. Every grain of personal communication and consumption feeds a further refinement of the algorithm that knows you, me, us. It’s so omnipresent, that you no longer need to be an anarchist anymore to long for opaqueness. While an external drive to be more present continues to fuel daily broadcasts of Your Authentic Identity, an internal voice wonders: How would it feel to disappear?”. The challenge of Get Rid of Yourself (Ancora Ancora Ancora) is in the experimental attempt to appropriate invisibility, in order to inhabit, at least for the duration of the exhibition, the operative concept of “getting rid of ourselves”. The narrations, the voices, the presences created by the artists in the exhibition turn the privative meaning of the expression into a collective space for the active sharing of practices. As Erica van Loon suggests in Your Brain Has No Smell (2017-2019) “How long does it take for your brain to realize that you didn’t blink but that I switched off the light?”

Elena Radice, Cantilena retorica per un futuro luminoso. Canone libero per coro polifonico disfunzionale, 2019, 18′ ca. Installation view, Fondazione Baruchello, Rome. Photo Alessia Calzecchi.

Methodological elements

Since Lucrezia Calabrò Visconti’s first inputs, Get Rid of Yourself (Ancora Ancora Ancora) looks at the exposition of sound without feeling guilty towards regimes of artistic research anchored to the notion of “objects”—the hi tech aesthetic of speakers and cables, the object that makes noise. The exhibition unfolds a path based on the relation between both sound and space, as well as sound and time, unleashing the whole performative potential of a recorded track. Here, sound is an event and embodies—intentional paradox—a perspective of the artistic doing rooted in its context. In fact, in its contexts, namely the exhibition space, the historical positioning, the spectator’s perception and the artist’s biography. We go on endlessly. In some ways, coherently to its title, Get Rid of Yourself (Ancora Ancora Ancora) is an exhibition out of control.

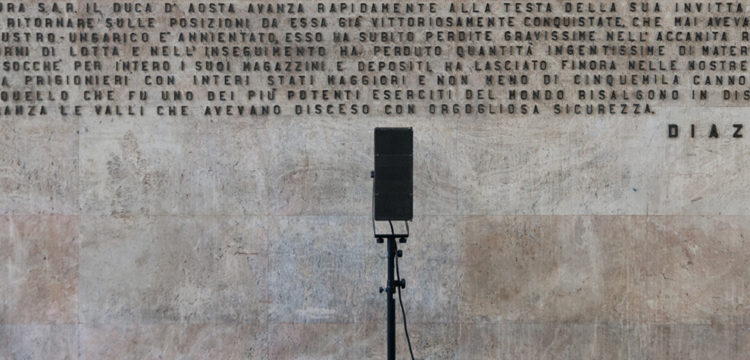

Almost deprived of their sight, the visitor is called to listen—listening intended as practice. In his short essay Listening (1976) Roland Barthes thinks of it as such: “Long before writing was invented, even before parietal figuration was practiced, something ws produced which may fundamentally distinguish man from animal: the intentional reproduction of a rhythm.” We could also mention Francois J. Bonnet who writes in his The order of sounds that sound “has functions to perform, expectations to meet, things to say.” And it is precisely on the performative functions of sound that the works’ formalization and installation is based on, defined in dialogue with the artists and the curator. From this point of view, there’s no dichotomy nor hierarchy between technical choices and aesthetics: the algorithm produced for Teresa Cos’ Archive of Loops, for instance, interprets the conceptual conditions of the work, inasmuch as the higher positioning of Dafne Boggeri’s speakers is propaedeutic to the environmental dimension of the intervention. Speaking of the speaker, we believe the performativity of the exhibition, explicitly emphasized by its duration, to be inspired by some syntaxes of acousmatic art, precisely on the trend developed around the new possibilities of the electroacoustic instruments, from the recording techniques to sound diffusion.

Dafne Boggeri, Starting the rhythm, 2019, 1’47”. Installation view, Fondazione Baruchello, Rome. Photo Alessia Calzecchi.

The acousmatic logic allows us to move around the space generated from the temporal gap between the output and its fruition. We wanted to play with the installation dispositive, within the language of visual art, by emphasizing the hybrid role of the speaker, that thanks to darkness is removed from its aesthetic dimension. The choice of media, as well as the diffusion and placement modalities are fundamental elements to the aesthetic means of the whole operation—thinking of Elena Radice’s work, and the choice to use a different kind of speaker, since the tracks are embodying a plurality of vocal timbers, each with its own expressive character. To manage the speakers means to interpret, to assume an artistic, directorial role, for the sound is directed through an ever-changing choreography of the output.

Get Rid of Yourself (Ancora Ancora Ancora) means to suspend the conditions that lower the potentiality of our daily soundscape. We could open infinite parentheses in regards to the art system, to the difficulties in assimilating the sound medium, but also to the resistance in including electronic music in the popular imaginary of the concert, where traditionally the musician-executor never disappear. To conclude, we wish for a perspective reversal, as we believe that performativity doesn’t require presence all the time, but rather in order to get rid of oneself, one could rely on the performativity of absence, of invisibility, of moving in the dark.

[1] Tiqqun self-proclaimed themselves the “conscious organ of the Parti Imaginaire”, and, according to some, they later merged into the Comité Invisible [Invisible Committee], a group highly influenced by the philosopher Giorgio Agamben, and author of the famous The Coming Insurrection (2007).

[2] In the words of Érik Bordeleau, author of Foucault Anonymat (2013): “If the government’s main operation of counter-insurrection is to constantly reinstitute a separation between an ‘innocent or vaguely consenting population’ and its most offence-inclined elements, the strategic conclusion becomes: ‘we must make it so there is no longer a population.’” https://onlineopen.org/who-you-are-is-but-a-manner-of-war

[3] This sentence might recall the so-called “decreto sicurezza-bis” [safety decree-bis] on “urgent dispositions in regards to public order and safety”, that was proposed by former Internal Affairs Ministry Matteo Salvini and became law in the Summer 2019. In addition to a number of frightful measures in regards of the management of rescue at sea, the law proposes a reform to the Penal Code in matter of the management of public order in occasion of any form of public manifestation. Among other things, the decree imposes the ban, to all participants to the manifestation, to wear any item or device that makes any person “unrecognizable”. Amnesty International commented: “The second part of the decree […] has the clear purpose of limiting the spaces of freedom of those who want to claim their rights and those of the community. On the contrary, we think that the discussion of this provision could have been an opportunity to open a debate on transparency measures for the work of the police, such as identification codes, to protect and guarantee the work of the agents themselves.” Amnestyinternational.it

[4] Mille e una luce was a twelve-part television program, broadcasted only in the summer of 1978, in which participants challenged each other to a game of team checkers. Thanks to an agreement between RAI and ENEL, viewers could vote for their favorite competitors by turning the lights of their houses on and off.

[5] The original video was manipulated in the following episodes: the frame was narrowed and duplicated in many small mini-screens.

[6] Stalder, State Technology: Data (2017), as quoted in A.Teixeira Pinto, Tuned to an Undead Channel, published in Metahaven PSYOP: An Anthology, edited by K. Archey and Metahaven, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam 2018.

[7] In an interview aired on RAI in 1989, the “bad master” of Autonomia Operaia justifies himself, almost amused, with the interviewer Sergio Zavoli, when he accuses him of “explicit, enthusiastic adherence” to the spirit of armed struggle, citing his words from Il Dominio and Sabotaggio [Domination and Sabotage], Feltrinelli, 1978: “Nothing reveals the enormous historical positivity of worker self-valorization more than sabotage. Nothing more than this activity of a sniper, a saboteur, an absentee, a deviant, a criminal that I find myself living. Immediately I feel the warmth of the working-class and proletarian community, every time I use my balaclava.” Negri replies to Zavoli: “The balaclava is put on by people as not to be recognized by the police, so as not to end up in jail; the balaclava was not used to attack, it was used to defend oneself.”