A Life Lived

Archive Actualized #7: a conversation with Associazione Culturale Alberto Grifi

The seventh appointment of Archive Actualized is the result of the collaboration between REPLICA and Associazione Culturale Alberto Grifi on the occasion of MAGNETE, a project dedicated to publishing curated by Gaia Bobò. The Associazione Culturale Alberto Grifi is committed to preserving and promoting the figure of painter and filmmaker Alberto Grifi. Known in particular for his use of experimental filming devices, he made his debut filming Carmelo Bene’s Cristo ’63 and collaborated extensively with the Roman avant-garde scene of the 1970s.

Replica: The Associazione Culturale Alberto Grifi was set up by Alberto Grifi himself. How was this decision taken and what was its mission?

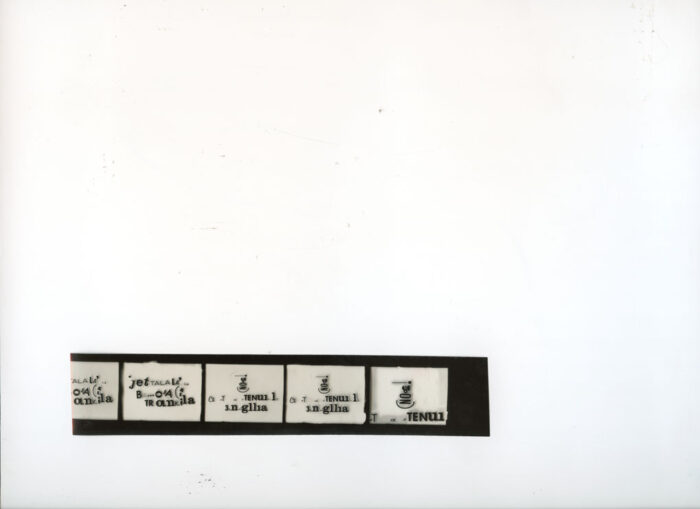

Associazione Culturale Alberto Grifi: The Associazione Culturale Alberto Grifi was founded in 2006 by Alberto himself to protect his legacy and promote, encourage, and implement cultural and artistic initiatives. Aware of the advanced state of his illness, at that time Alberto defined the guidelines of the Association personally and chose the first members: his son Ivan, Cristina Sammartano, Luciano Longo, Annamaria Licciardello and Sandro Costa, president of the Association and CEO of Interact, a Roman media company with which Grifi had worked for the last five years and where he had moved his office and archives. Together with Interact, in those years Alberto Grifi had focused his efforts on saving his works, those on analog tapes that had not yet been digitized and were in danger of being lost, such as Anna, Parco Lambro, and Gli autoriduttori al Convegno di antipsichiatria di Milano. The initial phase was therefore oriented towards the constitution of an archive and the storage of all the works, carrying out the necessary activities for their proper preservation and the first attempts to recover and digitize them in-house. Unfortunately, Alberto’s health deteriorated the following year, leaving us in April.

What forms has this project taken since Grifi’s death? What activities have you undertaken to promote his research and practice?

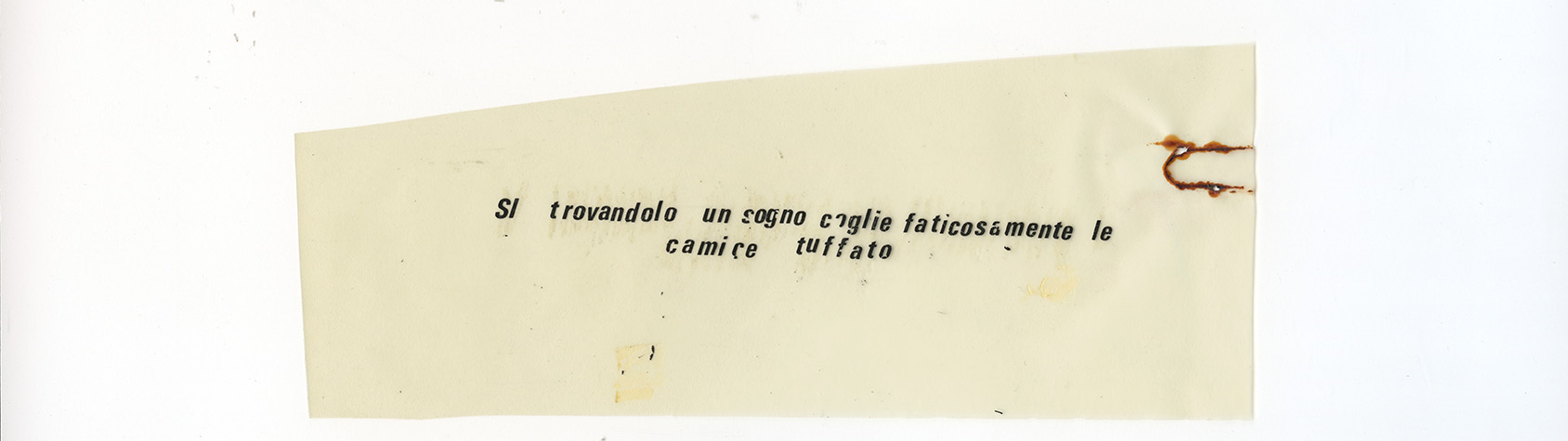

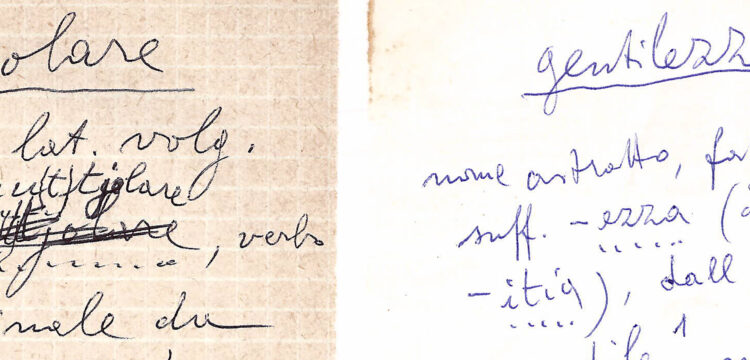

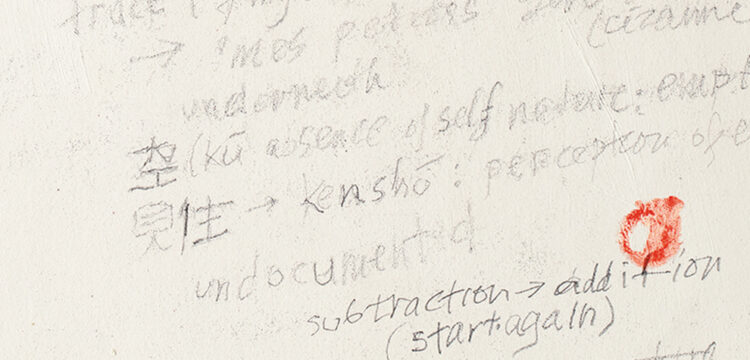

First, we inventoried and cataloged what was still in the archive and not yet seen or known. Alberto’s organization of the archive was very meticulous, inside large boxes labeled on the outside with information about their content. This unsystematic and structured system was essentially based on Alberto Grifi’s (artistic and otherwise) life path and memory. The boxes contain fragments of life, memories, and works, in an indissoluble interweaving, almost as if to metaphorically represent the impossibility of separating life and artistic research, that is the principle underlying the avant-garde and experimentation of the 1960s and 1970s, in a utopian attempt to reintegrate both—Putting our hands into Grifi’s archive to decode its cataloging logics and to make it accessible according to different logics, linked to research and analysis, was for us also an emotional journey and a journey of knowledge within his personal “memory”. It was not easy for us, because the feeling of violation of private and personal aspects was a constant in this phase.

Over the years, we have worked to enhance and promote the archive, collaborating with institutions such as the Cineteca di Bologna and the Cineteca Nazionale, but also with researchers and scholars interested in Alberto’s work. There have been many initiatives in Italy and abroad in which his most important works have been presented: Anna, Verifica incerta, and Parco Lambro. To mention just a few participations: États généraux du film documentaire; Venice Film Festival; Rome Film Festival; Rotterdam Film Festival; Berlinale; Cinéma du Réel; Tate Modern; Light Industry; Viennale; Lightcone; Spoutnik; Mumok; Amiens International Festival; Torino Film Festival; Centre Pompidou; Festival L’Age d’Or of the Cinematek du Belgique; Sao Paulo International Film Festival; Copenhagen International Documentary Film Festival; Paju DMZ Docs Festival; Lincoln Center; Marseille International Film Festival. We also remember the active interest of international artists such as Rachel Kushner and Constanze Rhum who have created some of their works inspired by Grifi and Sarchielli’s Anna.

In recent years, the cultural association has not only promoted the work but has also financed part of it, recovering and digitizing the original analog tapes of Anna, Parco Lambro, and Gli autoriduttori, saving them from deterioration and making them available for researchers. In the end, we managed to fulfill Alberto Grifi’s greatest wish in the last years of his life, which had become a real obsession, despite the disease that was progressing and taking his life, as if to testify to the need to “save” at least those images “of a life lived” superimposed on videotapes.

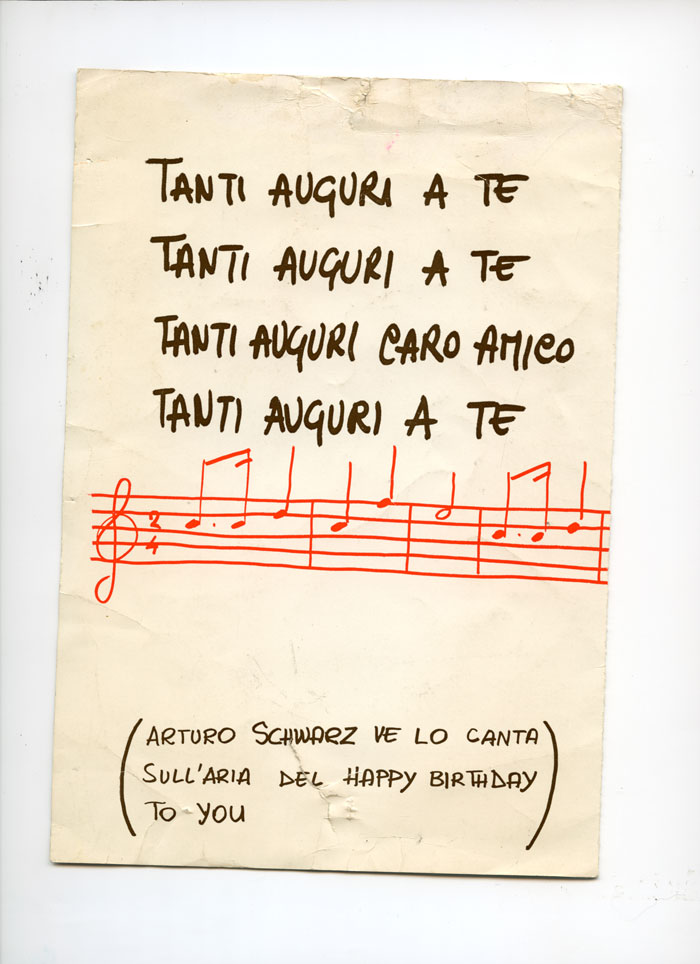

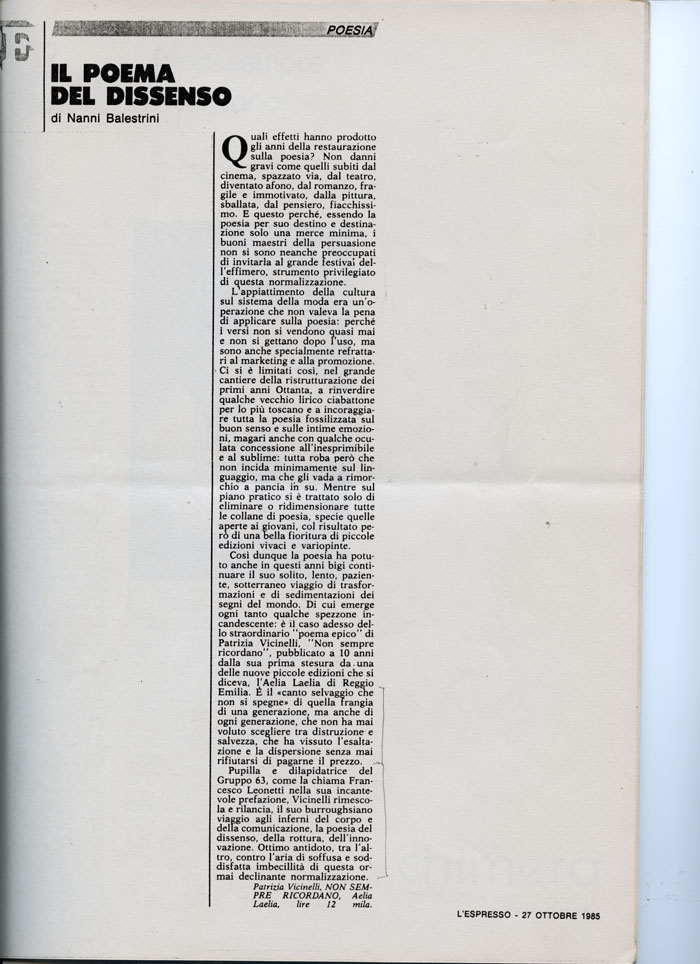

Alberto’s archive could be defined as plural. Many boxes and folders inside it are classified with names of friends and life companions such as Patrizia Vicinelli, Nanni Cagnone, Giordano Falzoni. How would you describe these collaborations intrinsic in his life?

As described above, Alberto Grifi’s life and work are strongly intertwined. Boxes with names of friends and life companions that contain evidence of their passage and influence in Alberto’s life, between life experience and artistic work, with no separating lines between the two: Patrizia Vicinelli, Giordano Falzoni, Alessandra Vanzi, Aldo Braibanti, and many others, including us, were part of that creative and artistic process, intrinsic to their own lives, which found in Alberto Grifi a “director” able to translate, through a never definitive crystallization, a flow of emotional interactions, exchanges, experiences, and dialogues. His works were never closed, always subject to new interventions, because they were closely interconnected with life and as such in continuous evolution and transformation. Even the presence of friends, who were often the protagonists of these works, was in harmony with this principle related to the phases and moments of a life lived with Alberto.

Due to their fragility, books, documents, and texts are often the most complex materials to display. You have lots of them. In addition to organizing events for screenings, have you ever thought of showing some of the documents you have in the archive?

Yes, we have often thought about it, but we have found many difficulties due to the nature of the materials and the need to create an exhibition and thematic routes that require time and specialized professionals, such as curators. We did something like this at one of the last editions of the Filmmaker Festival in Milan, but it was mostly installations or some photographic exhibitions in collaboration with some social centers. Recently, the solo exhibition on Patrizia Vicinelli at the Macro in Rome allowed us to show unpublished documents and materials from the Grifi archive, which was very important for us. We would like to continue in this direction, the archive holds small hidden treasures, fragments of an existential and artistic path yet to be discovered and enhanced.

What was the idea of the Archive for Alberto? How did he collect the materials now in your possession?

The archive has always been inseparable from both his life and work. Big boxes full of “finds” from endorsements to correspondence, from magazines to photographs and drawings, passing through notes and business cards. He maniacally kept everything, with a very personal logic of cataloging and searching based on his memory and the associations linked to it. Audio and videotapes, pieces of film, photographs, writings, drawings, notes, posters are stored in boxes ready to be reopened. Alberto Grifi’s was a “living archive”, an important part of his work, a continuous work in progress—files ready to be used in new projects that took up others that had never been completely closed.

When Alberto moved his archive and working space to the Interact headquarter in Rome, due to difficulties he experienced in those years and the necessity to leave his family’s historic home in Viale Carso in Prati, he transported on several trips with his car, the boxes of the archive and all the equipment for filming and audio-video reproduction, including vintage video recorders. In the new premises made available by Interact, which later also became also the headquarters of our association, we followed Alberto day after day as he arranged the transported materials, taking the opportunity now and then to ask him what the boxes contained. Alberto was quite jealous and protective of his archive. In particular, he was careful not to reveal the contents of certain materials: on the one hand, the most intimate documents, linked to his personal history (including family history), with letters, diaries, and notes. For years he had kept documents, especially videos, which contained hazardous material and were potentially dangerous for the safety of his “comrades”—trying to protect them had made his archive impenetrable.

In the initial phase of our common journey, every time our questions were too curios and became too “intrusive”, after staring at us for several seconds (today, after getting to know him better, we know that his pauses often implied a reflection that took him back in time), he would answer politely and punctually, filtering the topics and avoiding going into some of them in-depth. Over time, Alberto opened up more and more to us and consequently also “revealed” more private sections of the archive (also understood as memories linked to his own experience and personal life), both by telling long stories and sharing some of the boxes’ content.

As an antithesis to the idea of the exhibition, do you believe that the film medium can be an alternative and a tool to present the materials of an archive?

Although we are talking about different experiences, a film can certainly be an important tool for valorization and, in some ways, a more powerful means of conveying the contents and materials in an archive. For example, making documentaries on specific topics or figures in the life and work of Alberto Grifi, such as Giordano Falzoni or Patrizia Vicinelli, using the “testimonies” preserved in the archive has always been an idea which, for various reasons, has never been realized until now. But surely we are willing to evaluate possible collaborations with artists and documentary filmmakers interested in exploring this type of opportunity with us.