Bibliophiles’ dreams

Archive Actualized #2: a conversation with Alessandro Pasotti and Fabrizio Padovani

REPLICA has set down for a chat with Alessandro Pasotti and Fabrizio Padovani, founders of the gallery P420 in Bologna, which since its opening has shown a great passion for artists’ books. Since the start of their involvement with contemporary art, during their studies at the Faculty of Engineering in Bologna, the gallery owners have been interested in artist’s books and art catalogues, especially from the 60s and 70s, with a particular focus on Conceptual and Minimal Art.

REPLICA: Years before the opening of the gallery, you both were already interested in artists’ books and more generally to the art publishing sector. Would you like to tell us more about this starting point?

Alessandro Pasotti and Fabrizio Padovani: During the years we spent at the University of Bologna, we used to balance the highly scientific disciplines in our courses, such as technical training, mathematical analysis and construction science, with some more humanistic and artistic interest. So we approached contemporary art, a bit like many others, buying books to try to understand a bit more about it. Our attention was more or less naturally directed towards the avant-garde movements of the 60s and 70s. At a certain point we realized how much the documentation of that period was not just a bearer of content, but as an object, it had its own aesthetic preciousness. Subtly, we felt this certain fetishism for the object-book coming, along with the one for invitations, leaflets, postcards related to exhibitions that also were a keepsakes of it, even more than a few years later. A certain spirit of adventure—some might call entrepreneurial—we evidently had—although asymptomatic—must have pushed us to start dealing this very material, and that was it. In the space of a few years we met many book enthusiasts and collectors, and we also understood that the word “book” is reductive. The last step was then taken towards collecting artworks, and the art galleries world.

Once the gallery opened the interest in books continued to be carried on and stimulated. It is no coincidence, that you own and exhibit a proper bibliophiles’ collection. The practice of several artists you represent is also strongly linked to publishing, in all its various forms. This choice seems to intertwine with your personal story. Would you like to tell us how you usually develop your publishing projects?

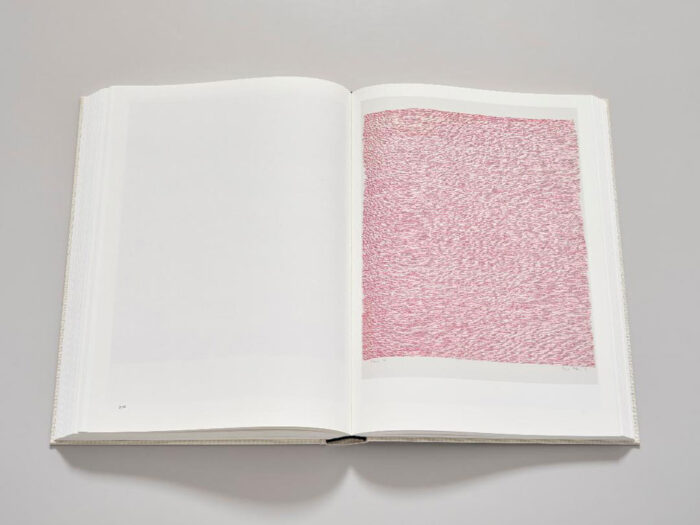

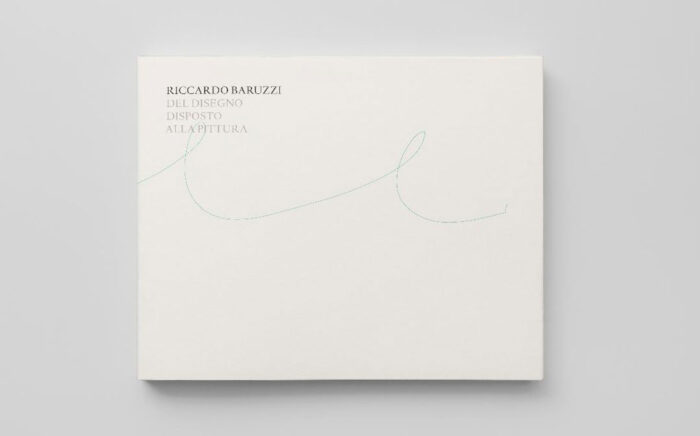

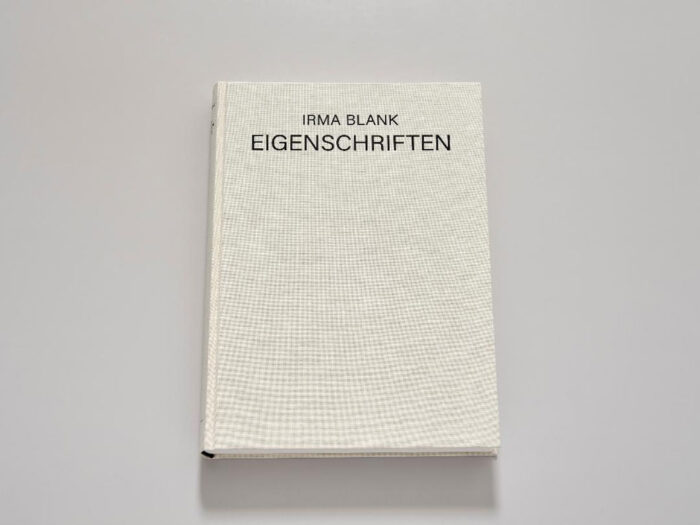

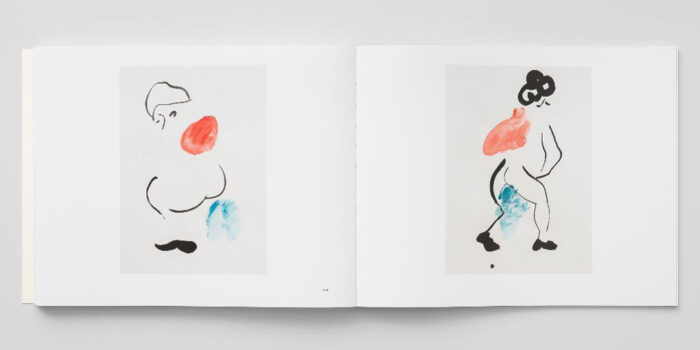

Opening a gallery is not an antidote for a books’ obsession, but rather something that greatly aggravates the situation. It is important to specify that we have never chosen artists to work with on the basis of their interest in publishing specifically, but it is undeniable that many of those we work with today, such as Irma Blank, Joachim Schmid, Alessandra Spranzi and Franco Vaccari have produced—and still do—beautiful artist’s books… Freud might have something to say about it… We are always available to support our artists’ publishing projects, whether they are artist books or publications related to exhibitions, or real monographs. We have produced many, and among the monographs we are pleased to mention Del disegno disposto alla pittura by Riccardo Baruzzi, Faredisfarerifarevedere by Paolo Icaro, Eigenschriften by Irma Blank and Constellations by Stephen Rosenthal.

Del disegno disposto alla pittura, Faredisfarerifarevedere, Eigenschriften and Constellations are precious art books sold at an affordable price. According to you, why are they artist’s books rather than art catalogues?

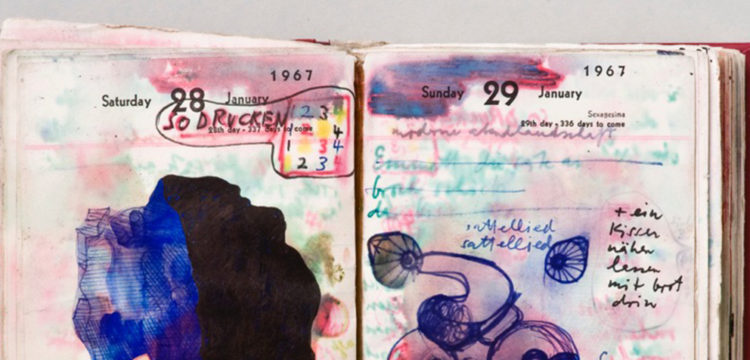

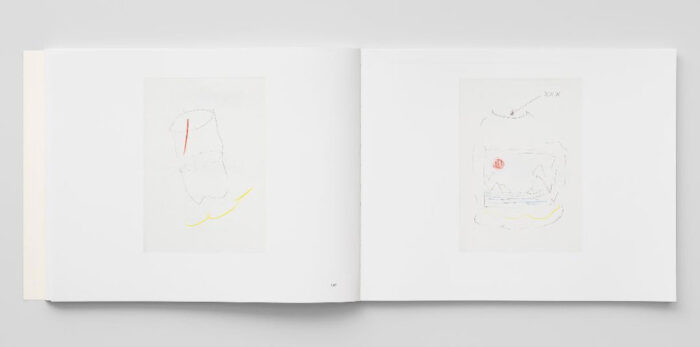

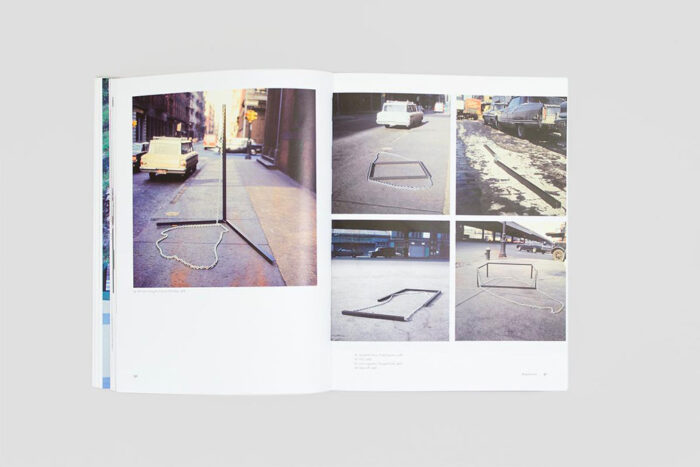

If we refer to these titles, it would be wrong to call them either artist’s books and art catalogues. They are not artist’s books because the content, the graphic design, the choice of images and the construction of the book itself is not chosen and followed personally by the artist nor does the book itself claim to be an original artistic content. We have just as much difficulty in defining them as art catalogues, a definition that immediately leads us to a somewhat reductive idea of an exhibition catalogue, then to a more or less curated selection of works presented in sequence. We define these volumes as monographs, that is to say books that present the artistic practice of a particular artist, along with critical texts and a selection of works and images. They can be either broad-spectrum, like Faredisfarerifarevedere edited by Lara Conte and published by Mousse, dealing with Paolo Icaro’s artistic production at large, from the beginning of the 60s until the date of the book’s publication—or they can be a in-depth of a particular moment within the artist’s production, as Eigenschriften published by Sternberg Press, which dealt with Irma Blank’s artistic debut between 1968 and 1973 when, in Sicily, she perfected and produced her first cycle of works which she called Eigenschriften, literally “writings for herself”.

How come are you so attached to these editions?

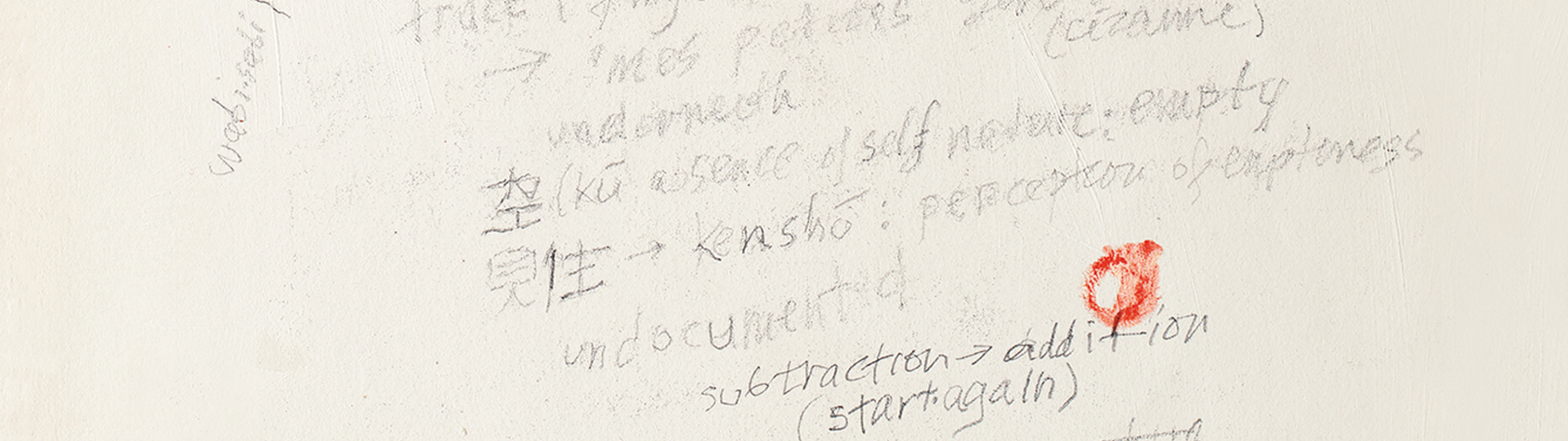

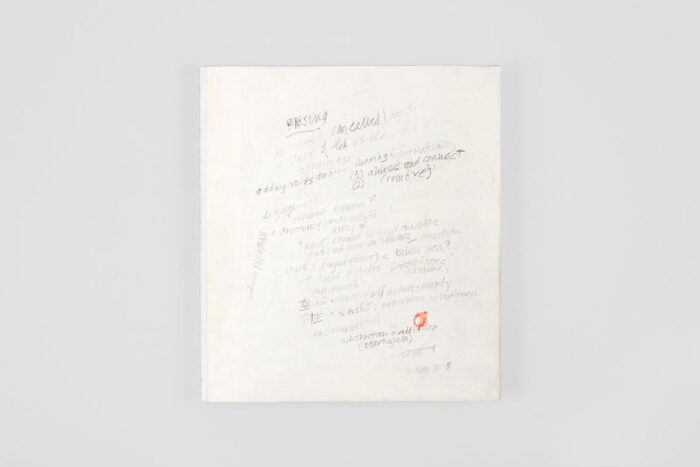

These books contain what we chose, what we love and what we would like to share with the world. There is great labour inside, both as gallerists and publishers. These books are the materialization of what we would like to let the world know about our artists, they are an attempt to convey at least a part of—for once, what we would like everyone to know. Let us tell you an anecdote on how the idea for a cover for one of our editions came about. When we organised our first exhibition with Stephen Rosenthal in 2018, he was hanging his apparently white canvases, with some marks and smudges, as the result of the self-erasure of his own paintings. He passed by the offices, he took a sheet of paper and began to write words on it, such as Erasing, cancelled, removed and other words that seem to fade and vanish themselves, all somehow connected to his work. In the end he filled the whole sheet of paper, which then became his work. When we later did his monograph, Constellations, that sheet became the dust jacket of the book and every time we pick it up we think about that moment.

One of the main fields of investigation of REPLICA is the display, to understand how to use the object book. In several exhibitions, such as Irma Blank. Artist’s books: editions and originals, Un’opera per un libro d’artista up to the most recent solo show by Alessandra Spranzi Mani che imbrogliano, you have used cases or tables as display. Have you ever thought about the possible limitations of these supports? How do you think it is best to use a book, especially when it is a rare edition?

Of course for artist books and rare editions in general there is always the problem of conservation, in contrast to fruition. Perhaps one of the moments when we most brilliantly resolved this eternal conflict was when we wanted to exhibit Irma Blank’s artist books. Some of them are indeed very fragile, like And so on… because it is dated 1974 and made with simple means. Or Ur-buch ovvero Romanzo Blu because its pages are in tissue paper. Others are particularly rare because they are produced in very limited editions. What we did was to make short videos, one for each book, lasting no longer than 30/40 seconds each, in which two loving hands caress and turn the pages. Anyone can imagine for a moment that those hands are their own, the rest is done by their eyes and emotions. Recently these videos have also been shown in Irma Blank’s anthological exhibition at Culturgest in Lisbon where the pages flicked through by these hands were frayed all over the wall in a dark room. It was beautiful.

The term bibliographic studio often generates confusion and misunderstanding, historically linked to a niche, these places seem halfway between a specialized library, an art gallery, an archive and a place of production. How would you define it?

The bibliographic studios we visited were places where we could spend hours extracting a small booklet from piles of books and be enchanted by them. Enchanted places outside of time? Yes, perhaps we would define them as such.

Can you tell us about some experiences made in these places? Which were the bibliographical studies you loved the most? Why?

When we first came closer to art and artist’s books, we visited two studios in particular. One was Giorgio Maffei’s in Turin—a cultured and kind man, a luminary in the field, perhaps the first to have had a scientific approach to this material, particularly in the 60s and 70s, working on cataloguing and historicization. The second was Carla Roncato in Milan—a funny and serious professional, out of the box, who would talk about her books for hours. Although they both left us too early, they surely left their mark.

How could these places be better known and attended?

The knowledge and passion of those who carry out these activities every day is the most compelling thing. I advise everyone, even the very young, to take a tour sometimes.

Our research is pushing us to pay attention to those artist’s books resulting from subversive and stratified practices—those objects that become atypical spaces for research and diversified languages, impossible spaces in which hierarchies are abolished. As collectors, amateurs and researchers of these works, do you think that the object book can be the place where artists can find greater freedom of expression beyond their specific language? Do you consider the artist’s book as a subversive object in regard to the usual dynamics of the art world and the market?

The artist’s book is perhaps a more direct space, in which the artist addresses the public without mediations, conceiving and publishing it, sometimes even self-producing it. Moreover, the fruition of a book is much easier than an artwork or an exhibition, it is within everyone’s reach and can spread more easily. There are no obstacles for ideas, it is a very efficient weapon. It is interesting to use the word subversive related to an artist’s book… yet, I don’t think it can be subversive within the dynamics of the art world. It’s as subversive as a book might be today, in general, that is apparently unconventional…