A Lifetime Library

Archive Actualized #6: a conversation with Fondazione Baruchello

Archive Actualized is a series of interviews, a format that aims at exploring some of the Italian and international artist’s books archives and bibliographic studios. For the 6th issue, Replica is digging into the library of the Fondazione Baruchello, in Rome, with the president of the Foundation art historian and curator Carla Subrizi.

REPLICA: Together with your collection of works and the Veio’s Park, another pillar of the Baruchello Foundation is the library, which holds various funds and around forty thousand volumes. Among these, there are Camillo Manfroni’s, an Italian teacher and politician who was one of the founders of the Naval League. How did these books reach the Baruchello family?

Carla Subrizi: Maybe first it’s important to mention that the Baruchello Foundation was set up in 1998. It has a collection of around 500 works, unrealized projects, drawings, film material, books, archives of correspondence and press material that narrate and contextualize the work of Gianfranco Baruchello. Baruchello is an archivist, in the most specific sense of the word—and this is part of his practice at large.

The Foundation’s country building, in Via di Santa Cornelia, has a wide park of 10 hectares. The area in which the historical building of the Foundation is located is the Veio’s Park, a context of great archaeological and agricultural importance. For us, being a small part of this great park has been a pretext for many projects, as it used to be for Baruchello before the Foundation’s birth. Apollo, Fufluns and Etruscan roads continue to remain important landmarks of that territory which is still part of Rome, even if only twenty kilometers away. This site, which until 1998 was Baruchello’s studio-house, was also the context where the activity of Agricola Cornelia (in the Seventies) was settled. Then in the eighties a garden was set up where the fields once were. Today, other projects have sprung up between ecology, art and the environment, which continue to characterize the special nature of this place. Without this “history” it wouldn’t be possible to understand the Archive and Library of the Foundation.

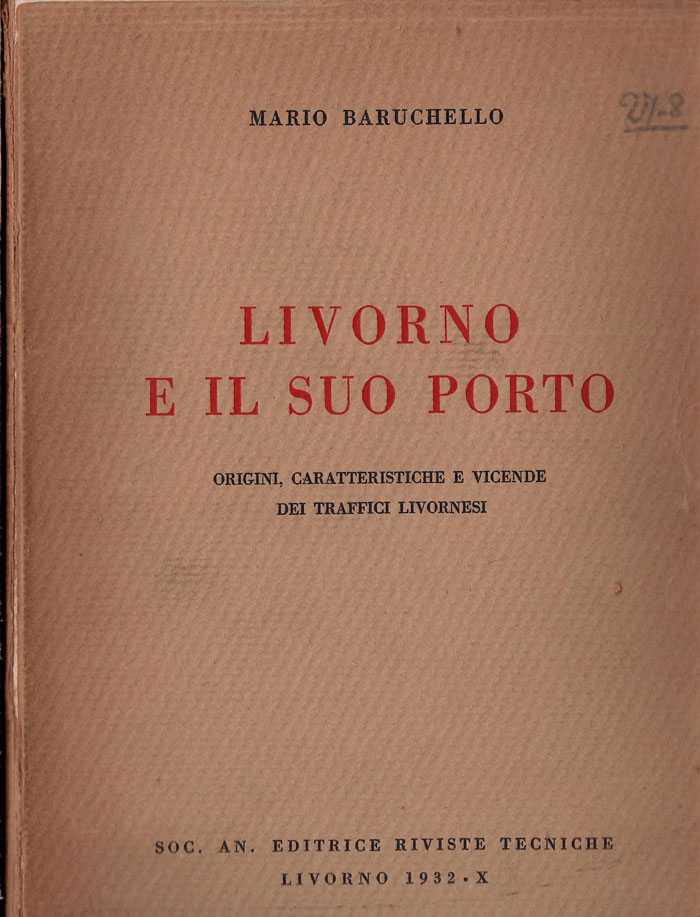

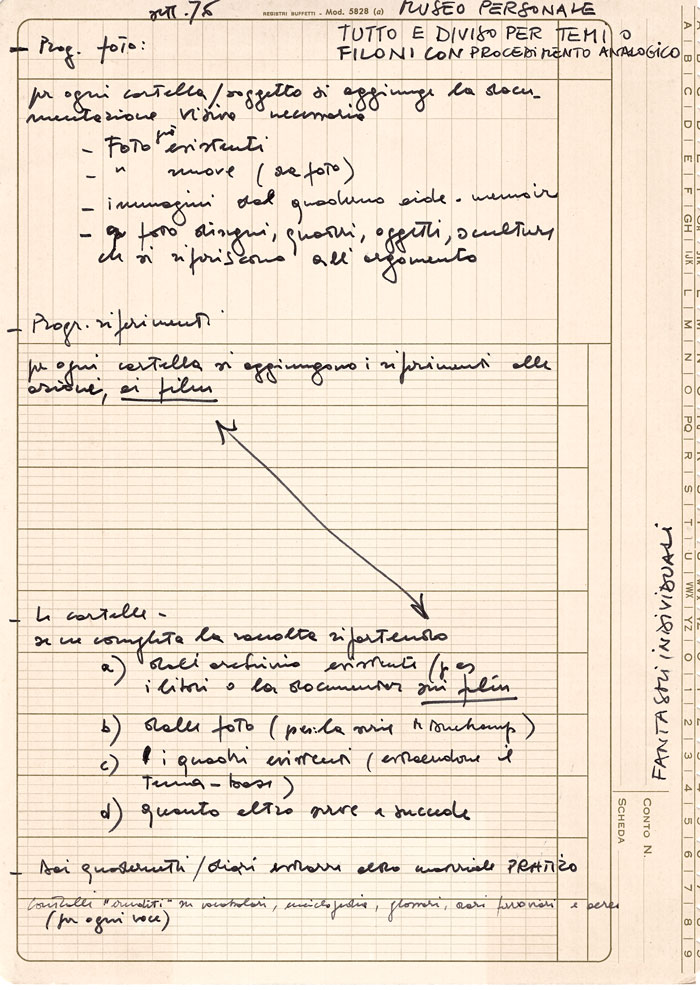

I believe that the library is truly an image of this complexity. Books, fonds, and curiosities that belong to it, were preserved by Baruchello over time. His interests, the infinite versatility of his orientation towards so many topics, themes, subjects have become a part of the library. Over time the shelves have grown because the books have increased and, importantly, Baruchello has always kept everything. He also inventoried, named and classified every section of his Library and Archives. Without these books, without the encyclopedias and dictionaries, without the books of his family (his father was the author of the book Livorno e il suo porto, and his “grandfather” was Camillo Manfroni), this great deposit of ideas would not have been constituted, which, like the great quantity of photographs, cuttings, present in part of the archives, are reactivated in Baruchello’s work, as well as in the projects of other artists with whom we have worked since early 2000s. So, the Foundation’s library is not like any other. It is a project that has grown over time. It is a portrait of what has happened in about 50 years of history, from when Baruchello moved to the country in 1973 and since the birth of the Foundation, in 1998, when I joined and contributed to the expansion of the library first as teacher and curator, and later as president of the Foundation.

The Camillo Manfroni Fund includes various editions including publications and magazines about the History of the Navy and the Colonies (1870-1940), History of Medicean Tuscany and the city of Livorno, as well as Economics and History of the Fascist period in Italy. Are there any rare or valuable editions you would like to tell us about?

Colonialism and fascism are recurrent in many publications. Camillo Manfroni was the brother of his paternal grandmother (the mother Luigia Manfroni of Gianfranco’s father: Mario Baruchello) and to Baruchello he was like a grandfather. He instilled a great curiosity in his little grandson—he died in 1935 when Gianfranco Baruchello was 9 years old. Camillo was Giuseppe’s son (he died in 1917) and the latter was a key figure in the relations between the Vatican and the State. On the Threshold of the Vatican—Sulla soglia del Vaticano. Memorie di un commissario di Borgo is one of his books, resulting from a selection from 19 handwritten volumes that he himself had composed. The published edition was edited by his son Camillo. Four or five of these handwritten volumes are at the Foundation. They are precious because they have missing pages and contain parts that Giuseppe did not select because they were perhaps more daring within the historical account he had given. Camillo published books on Italian colonialism during the middle ages and the renaissance, and on naval history. This part of the library is therefore to be considered as part of the family library: volumes and characters that were the context of Baruchello’s own childhood. This part of the library has been moved, refurbished, until it found a home in Baruchello’s study house in 1973. Then it remained there. So, these books and the whole Manfroni Fund are a memory of a past and of many issues that Baruchello, who was born in Livorno, also experienced personally. The attraction to the sea, and sailing alone, but also the melancholy of the years of Fascism, when he was a little Balilla, are demonstrated by the large number of books preserved, from his ancestors, but also alongside books by sailors, nautical magazines, volumes on sailing boats, next to which it is possible, if anything, to find hanging on the wall the photographs of his father’s sailing boats, on which Baruchello and his brother Leopoldo spent many summers during their childhood and adolescence.

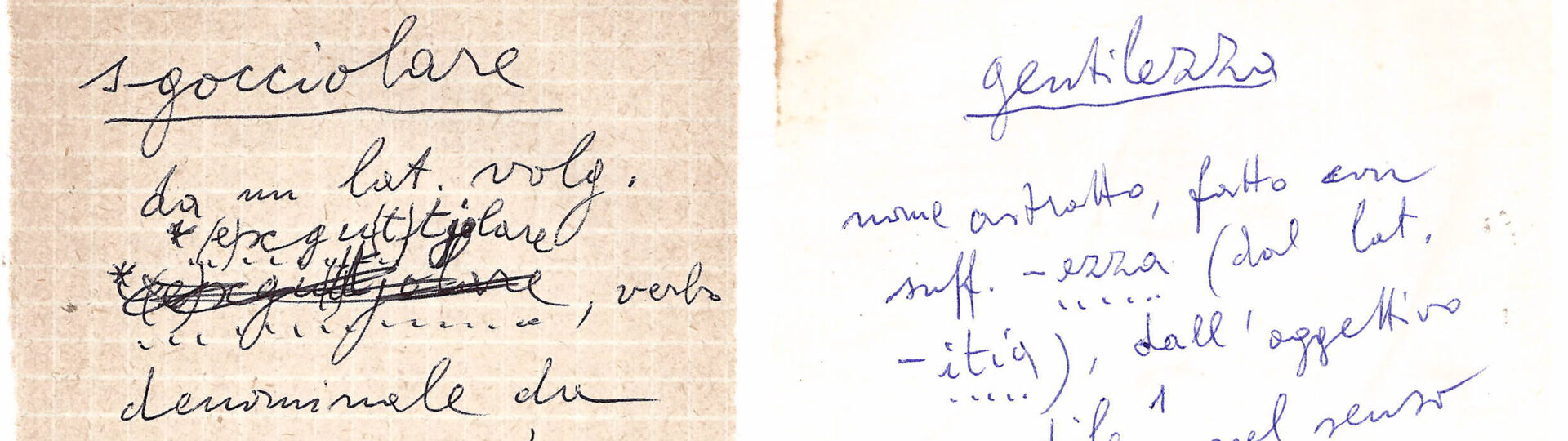

There are three places in the world where you can consult the manuscripts of the poet Emilio Villa: the Panizzi Library in Reggio Emilia, the Carale Museum in Ivrea and the Baruchello Foundation. Among the materials preserved there are two unpublished and precious manuscripts: the Etymological Dictionary and the Mythological Dictionary. As former director of the Panizzi Library Maurizio Festanti recalls, the poet “incessantly researched and manipulated etymologies until he obtained texts that are unheard of multilingual tangles; he made ‘objects of poetry’ and artistic artefacts as concretions of words–equally alive with meaning and sign–in poor materials; he has stubbornly edited his dictionaries and filled in cards and index cards–fragile sheets of paper cut out by hand–in order to draw up a new etymological dictionary of Italian that would be more sensitive to the contributions of Middle Eastern and Mesopotamian languages; he has written a mythological dictionary that, like the etymological one, has remained unpublished.” Can you tell us more about these volumes?

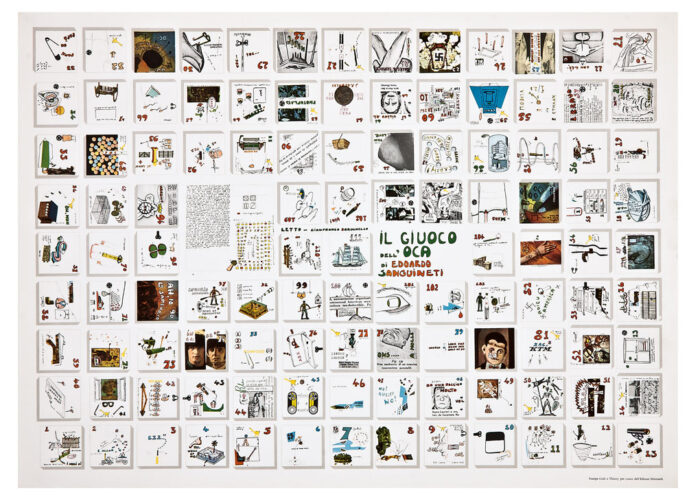

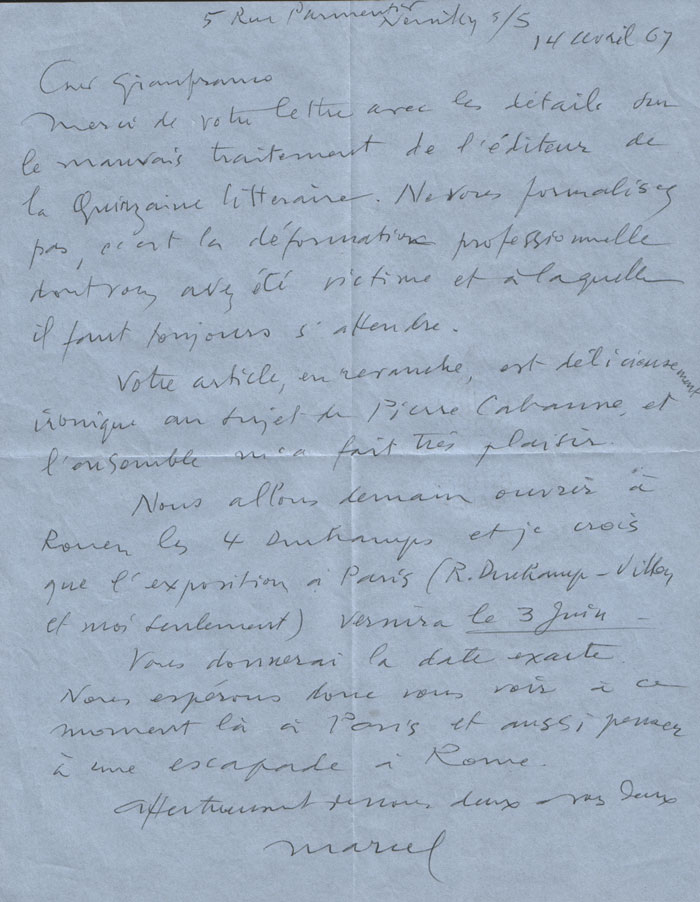

This part of the library was also born out of the relationship of profound admiration and esteem that bound Baruchello to Villa. When we decided to host this part of Villa’s documents, manuscripts and books (after Villa’s death in 2003) there were two strong motivations behind this choice. First, we thought of opening a “house of poetry” together with Nanni Balestrini. We gave a lot of attention to young poets. Four editions of the RomaPoesia festival in Rome were held at the Foundation and artists and poets occupied or transformed whatever space was available. For Baruchello, Villa always represented the figure of a dissident: an anomaly in Italian cultural history and, at the same time, one of its riches. Baruchello remembers that Villa was to write a text for one of his exhibitions, but Edoardo Sanguineti had just collaborated with Baruchello on both the book Il gioco dell’oca, published by Feltrinelli, and the exhibition Limbeantipouvoir at the Yvon Lambert Gallery in Paris. Could Sanguineti and Villa have written for the same artist? With an ironic but firm tone, Villa wrote a letter citing the name “Sanguinettti”, deliberately misspelled. Was this collaboration to be understood as a betrayal? These facts did not fuel siding or contrasts but instead admiration toward a figure, namely Emilio Villa, who had at every juncture of his life studied, written and translated into ancient and modern languages. But he also made notes, tore out pages from books (almost always those in which his text appeared), and took notes that were then accumulated in boxes and temporary or wooden wine crates. The two dictionaries (mythological and etymological) are undoubtedly a large part of the archive for us. This collection also shows how different parts of the Foundation’s library ultimately form a complex picture of a long history of friendship, curiosity and passion.

Looking closer, it seems that the Baruchello Foundation library has a great interest in poetry and in visual poetry. In fact, another important collection is Nanni Balestrini’s, an Italian poet who joined the neo-avant-garde and the group of experimental writers gathered within the anthology I Novissimi, later known as Gruppo 63. Why this attention to visual poetry?

With this question we continue from the previous answer. Poetry was perhaps Baruchello’s first “artistic” test. Even before he put his hands on a pen or pencil, he wrote poetry. Many are written in diaries, which have always been in Baruchello’s pocket or bag. The archive preserves these diaries, notebooks and notebooks and in them we find Baruchello’s poems written, then selected and rewritten, chosen or then given to the press. Baruchello wrote so much: poems, short stories, novels, books that were considered by critics to be “new adventure novels” and were instead transcribed dreams and then linked by standardising the name of a female character. Poetry was fundamental for his education: French poets, the Crepusculars, the Italian poets of his time, Villa and even Pasternak. I remember that hanging in his study when I first met him was a photocopy of a poem by the Russian writer that began with something like “To be renowned is not beautiful.”

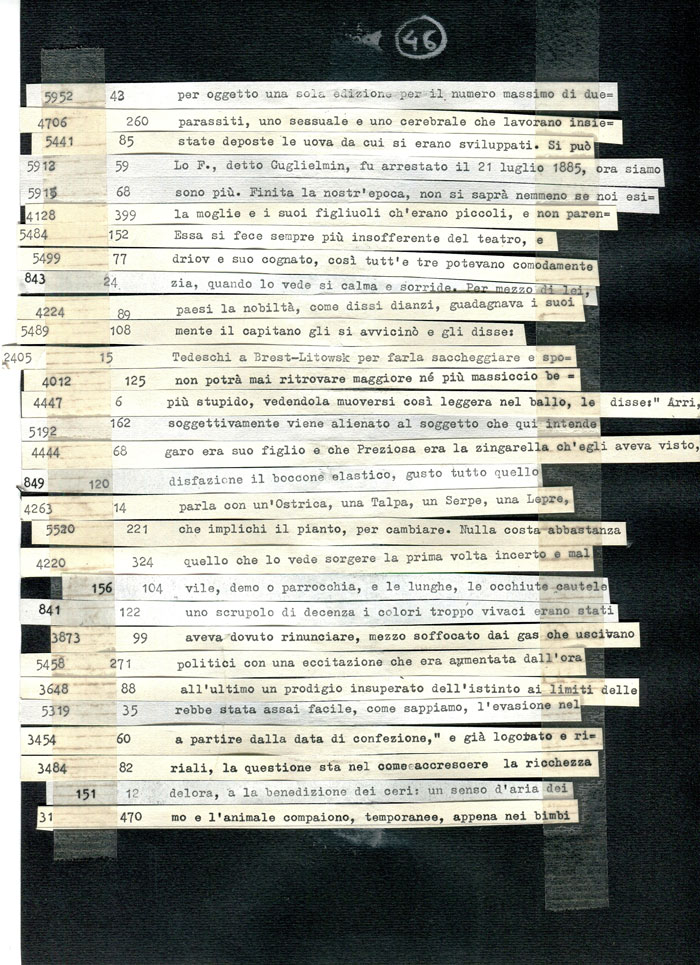

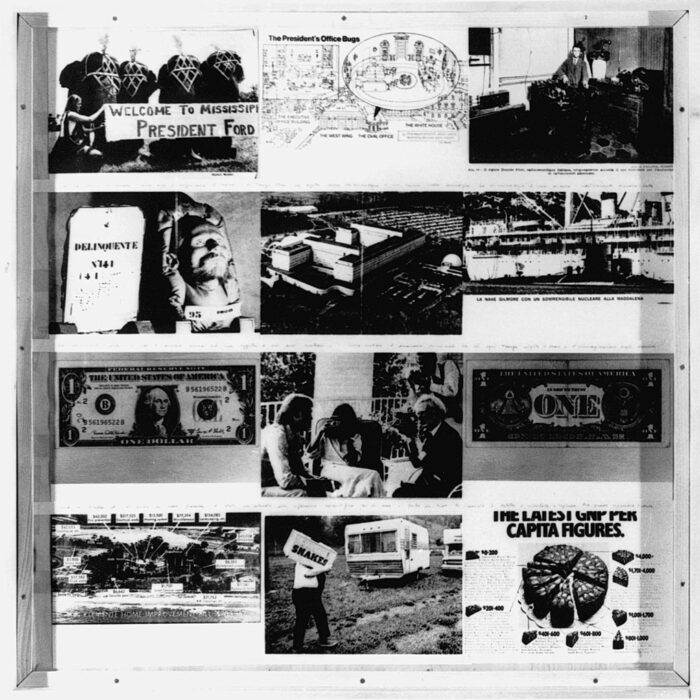

The word was thought of and used as an image. I don’t know if that is visual poetry. The fact is that Baruchello made expressions that can also be cited in this context: La quindicesima riga (1968, the fifthteenth line). Therefore poetry occupies many shelves in the library, which first belonged to Baruchello and then became part of the Foundation. The Foundation inherited these interests and developed them with the attention given to the younger generations. But the fact that Baruchello’s great friends were Patrizia Vicinelli, Nanni Balestrini, Alain Jouffroy, and that he had many collaborations with Corrado Costa, Adriano Spatola, Franco Beltrametti, and Sanguineti himself, slowly led to the implementation of the library with gifts, books sent by these friends. So, this part of the library can also be the starting point for finding letters, for discovering relationships, for finding, in a corner of the Archive, a folder containing poems written by poets and artists for Baruchello himself. There is even one by Scialoja. The Foundation’s library is—we could really say (and I got this idea as I searched through it or studied some of the sections)—a sort of bumpy ride through a history of relationships, interests and multiple curiosities. Adventure, navigation and agriculture coexist with poetry, politics, the history of fascism (which Baruchello continually rereads to understand how such a moment in Italian history was possible, even for his own life), nonsense and dictionaries on any subject. An “encyclopaedic” curiosity (and there is enough of encyclopaedias, from Genti e Paesi to Treccani, Britannica and The American peoples encyclopaedia) that has been deposited on shelves, in archives and in magazine collections. All this material is also fundamental for me and for those who want to study Baruchello’s practice because in the cut-out pages, in the underlining of the books, in the words, for example of the letters of Joyce and other authors, one discovers the possibility of a philological research that illuminates the titles of works, the words quoted in them, poetic universes that live in the same way as the images of his paintings. So, the whole library is an immense artist’s archive that is continuously reactivated both in the works and in the written texts. A recent work by Baruchello, published last year, the Psicoenciclopedia Possibile (published by Treccani, graphic design by Edoardo Visalli, conceived with Baruchello to look as much as possible like a “real” encyclopaedia) is a work that brings any part of this Archive to life: everything they have collected over time has been deconstructed, dismantled and reassembled for this volume, even the archives of clippings and what Baruchello calls “photos of photos”. It is an anomalous but very lively library. There is not everything in it: Baruchello (we have done this with more care since the Foundation was set up) did not want to collect poetry or visual poetry. He himself worked in verbal-visual and conceptual directions and traces of this and of his relationships are everywhere.

The Foundation’s programme includes initiatives linked to research days, reading and discussion of printed material (publications, magazines, catalogues). How do you structure these conversational events? How do these materials become the protagonists and how are they crossed and explored?

I would say that dialogue is at the heart of our activities: dialogue as a search for a plurality of points of view to try and bring together. Many of our activities have been based on the idea of the workshop. In 2003, when our programmes started to be more precise, we did not want to hold exhibitions but to seek forms of encounter and education. Education was born from doing and thinking together, from study and research, which were the basis of the very progress of the workshops. We worked on concepts (sharing, for example, with Cesare Pietroiusti and Emilio Fantin, in 2003-2004), on language and its transformations in the era of migrations and cultural displacements (with Stalker in 2005), we worked on how a “foreigner” in Rome and a group of young people born in the 1980s and 1990s could reconstruct a season like the one in Rome in 1977 (with Rogelio Lopez Cuenca in 2007). For us, these activities were not to become the stages of a pre-established programme, and so over time we changed the formats, and worked on themes related to political ecology (starting with Felix Guattari’s concept of “ecosophy”). Many of our activities arose from asking ourselves what paths and perspectives could be created by many of the themes of Baruchello’s work. Many projects were born out of an increasingly lively exchange of experiences and perspectives between Baruchello and me since 1997. My skills have been brought into play in the Foundation’s activities.

Politics, environment, archaeology (we are in an Etruscan area) have been the starting points for many projects. Then, since the addition of the new headquarters in Via del Vascello, in Monteverde Vecchio, our activities have been even more oriented towards capturing the research directions, intentions, tensions rather than trends of the younger generations. We realize that this is not easy. Today, very soon young people have a gallery, they have a critic who supports them. We would like to grasp what is happening among the younger generation before it becomes a “trend”. We have not yet understood whether it is possible and how a non-profit space such as a Foundation can have a fundamental function not only of increasing visibility, but also of deepening “works” and “ideas” in progress. We are interested in capturing ideas, in circulating them, in contributing to their production.

Besides the public programme, you usually organise a summer show. Even though some exhibitions have presented sections dedicated to books and narrative practices, have you ever thought of dedicating an exhibition entirely to books? Have you ever thought about forms of display that would move away from the usual display cases?

Yes, we have a lot of ideas about that. We also had an exhibition in which we displayed on an entire wall (more than 10 metres wide) about 200 books that were nothing more than an attempt to show Baruchello’s archive. These books, made of photocopies without interpretation (i.e. without “editing” but leaving both the sequence of the materials and their position as they were originally), turned the contents of a hanging folder of an Olivetti chest of drawers into one or more books (100 folders produced 200 books in a single copy). So, we are thinking of books that are also graphically research-oriented: new formats that use precisely the idea of the archive as a concept. There will be another one coming out soon.

Your library not only holds books but also photographs, films and videos. The most interesting collection is the one linked to the Alberto Grifi Fund, a figure considered one of the greatest exponents of Italian experimental cinema and who became famous for having filmed Carmelo Bene’s Christ ’63. The fund came to the foundation thanks to the collaboration with Gianfranco Baruchello for the 1964 film Verifica incerta? Could you tell us about the relationship between the two? What materials do you have at your disposal?

I don’t think that Alberto Grifi’s collection is the most interesting, just because we have very little of Alberto’s. We have a lot of Alberto’s books only because he lived almost all the last years of his life in one of the houses around the Foundation’s headquarters, in the countryside. When he left the house everything that was not taken by his children and by those who now look after Alberto (the Alberto Grifi Association) was kept by the Foundation. The Grifi Fund consists of these books and little else. The moviola with which Alberto worked, but also two other moviolas by Baruchello, are for us an important heritage that we preserve as if they were artefacts of 1960s technology. So, the important part of the photographic and film archive (Baruchello made about 100 “films”–and he defines films as those lasting just a few minutes) is made up of the photographs and films, and the many films he saw and collected. The photographs taken by Baruchello from photographs, according to a method of “appropriation” that has never abandoned him since Verifica incerta, are in dozens of boxes. Then there are the “very small photos” that were created to make the original photo almost invisible (the photograph or the television screen was reduced to a size of about 1×1 cm). There are also the photographic “series” including those taken of Marcel Duchamp in 1966 and other photographs that have never, we might say, been exhibited. With these experiments he participated in Fluxus festivals and proposed projects to Billy Kluver. In short, starting from Baruchello’s work, the library has been forming (or per-forming, as dear friends would say) as an accumulator of everything that in some way preceded, or constituted a passage in, Baruchello’s work. Is the Library therefore the most important source for studying the work of this artist? And at the same time to find within it a multiplicity of ideas, materials, documents, which have accumulated over time, until they become unique sections for what they contain? Many scholars find books here that are not known elsewhere. Or leafing through notebooks or other archival materials, they discover unpublished aspects of people who were part of Baruchello’s friendships and relationships. The Foundation itself was set up precisely in order not to disperse, to try to conserve but at the same time continuously reactivate an immense, varied and diverse amount of material. A library that is unique in some ways, like any artist’s library, but has grown meanwhile, perhaps in a more targeted way, since I myself began to increase its holdings with magazines, books on art history, and Italian and international criticism.

REPLICA is also a small archive and a collection of books. We would like to know more about the ways in which you are currently working on Gianfranco Baruchello’s Catalogue Raisonné, what form you are giving the project and what rules you have decided to follow.

I believe that the Catalogue Raisonné is a project, for anyone who undertakes this work, that reflects not just one methodology. A Catalogue Raisonné should really be a portrait of an artist’s work. By its very nature, it encapsulates the work down to the least known details, and by bringing the best known and the least known to the surface, it challenges many of the paradigms underlying historiographic research. So, the editor of a catalogue raisonné has the difficult task of constructing this portrait. But how do we reconcile the detail and the macro-history of art? How does the catalogue raisonné contribute to art history itself?

My research on Baruchello coincides with many questions which, also by studying other artists, have become increasingly clear and defined. There are many rules to be laid down and it is difficult to talk about them. However, we will be able to talk more about the catalogue when things are done, in about two years, and if necessary, in an interview dedicated to this project.