A Catalogue of Catalogues

Archive Actualized #4: a conversation with L’Arengario

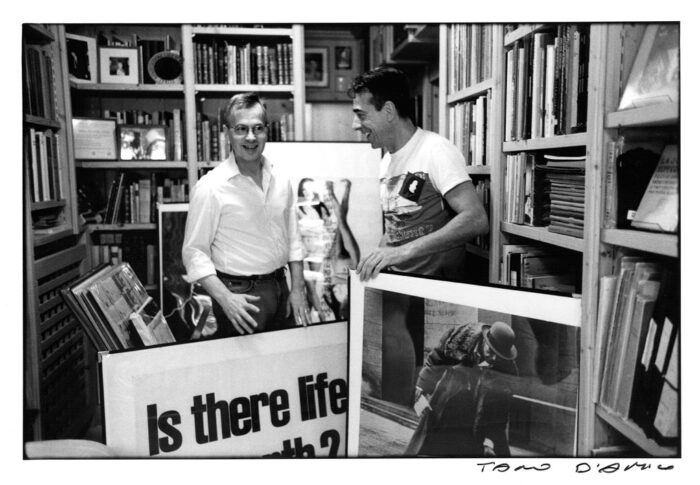

For the fourth issue, Replica decided to continue with an institutionalized and well-known archive, namely L’Arengario Bibliographic Studio. In conversation with Valentino Tonini, son of one of the two founders, REPLICA explored the story of the studio and its cataloguing and exhibiting activities. L’Arengario was founded by Paolo e Bruno Tonini in 1980 and is specialized in avant-garde history, artists’ books and protest culture.

REPLICA: It is difficult to give an unambiguous definition of what is called a bibliographic studio. These places can be: print and art book galleries, small publishing houses, antiquarian bookshops, archives, meeting places for enthusiasts. In regard to your long experience, which began in the early 1980s, how would you answer the question: what is a bibliographic office?

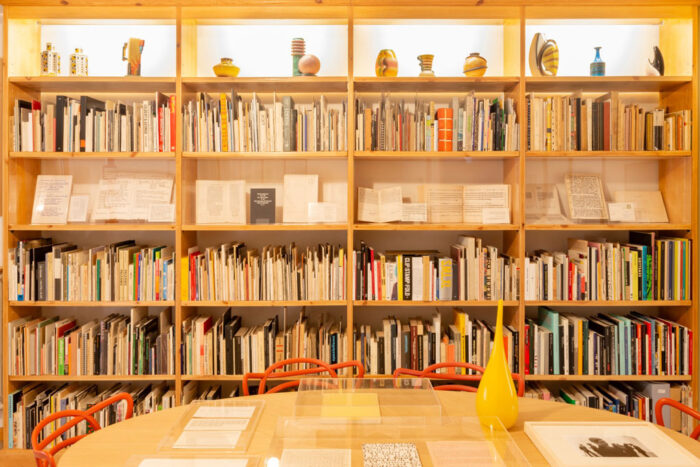

Valentino Tonini: The Bibliographic Studio is a place where an activity, quite similar to that of a normal bookshop, is carried out selling rare and out-of-commerce books and documents. The only difference is that the working space is not a public place. In our case, but also in some other similar cases, the activity of the Studio has not been limited to carrying out the normal activity of book trade but has also developed into a place of research and study of the books and documents owned and accumulated over many years in monographic collections.

One of the most important aspects of the activity of a bibliographic studio is the production of a catalogue of the volumes on sale. This object, as precious as the books it collects, manifests the identity of the study that produced it. How do you develop the editorial idea and the process of creating a catalogue? Which catalogues are you particularly fond of and which have marked specific research projects?

In forty years of activity, we have published over 350 catalogues, 250 of which are monographic on modern and contemporary art themes, inspired mainly by personal interests, very often by reading a book or after a trip, sometimes by a visit to a museum or a collection. Our editorial activity has always been conditioned by the rigid conviction of producing only catalogues that are as exhaustive as possible on the subject matter and objectively useful for the study of artistic documentation. To achieve this, we often find ourselves researching and accumulating material for a long time before actually selling it. This prerogative has constantly marked our working path, a recent testimony of which is the Catalogus, or “The catalogue of catalogues” edited by my uncle Paolo, published last December to celebrate the studio’s forty years of activity. Each member of the studio has a preference for one catalogue over others, from those we have dedicated to Futurism, in which we have been assisted in our work by scholars such as Claudia Salaris, Pablo Echaurren and Maurizio Scudiero, to those on Abstractionism, produced with Maurizio Fagiolo Dell’Arco and Piero Dorazio, who designed the cover for one of these, or the more recent catalogues such as the one dedicated to Hanne Darboven or Arte Povera, which I personally find closer to my interests.

How did you structure this Catalogus? Don’t you think that it might be necessary to turn these collections into an object of study and research?

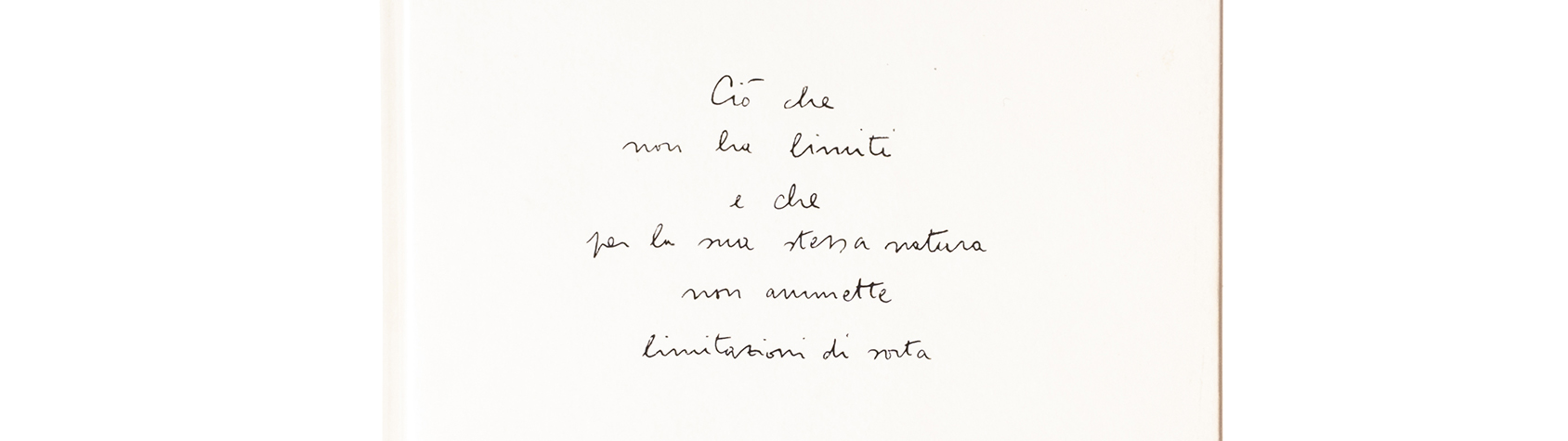

The Catalogus is made up of two parts: in the first one, all our catalogues are described, from the first to the last, in chronological order; in the second one, we have collected various testimonies from friends, colleagues and people who have accompanied us along our journey, whom we have asked to dedicate a text, a thought or a memory linked to our history. In this large book, my uncle Paolo wanted to collect all our production in order to make it available to anyone who wants it, describing the content of each publication, mentioning the most important books and some anecdotes about its realization. We are aware that our activity is an anomaly in the world of bibliophilia and telling the story of two brothers who live their dream by creating hundreds of catalogues through a catalogue seemed to us the best way to do it.

Has it ever happened that you have refused to sell a book because it has acquired an important value for your collection?

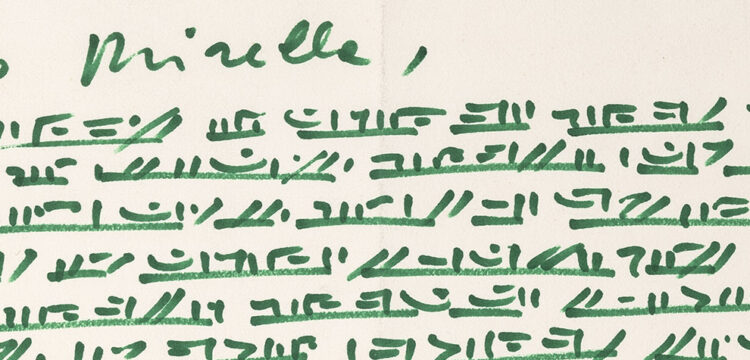

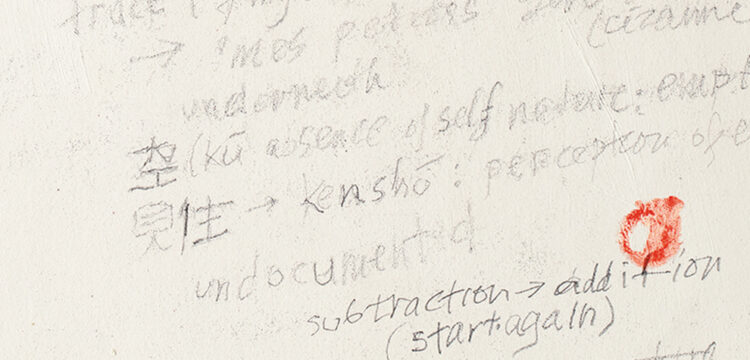

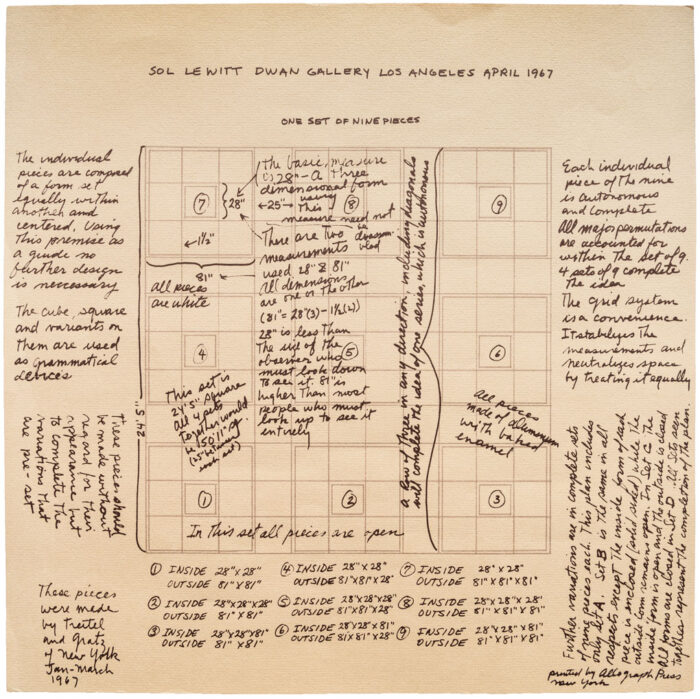

It has happened many times, which is why today we have a significant collection of artists’ books, catalogues, posters and a very important collection of invitations. Being scholars, collectors and dealers at the same time is very difficult and when faced with a particularly rare work, we are almost always forced to find a compromise between our different natures. However, it has often been the case that the collector’s nature has prevailed, supported by the scholar’s nature, for example with Sol Lewitt, whose entire printed production we have collected: artist’s books, posters, invitations, photographs and numerous original documents. They are all jealously guarded in our studio. For some years now, we have been concentrating on expanding the collection of artists’ invitations, a relatively new field, which my father Bruno has outlined in the book Artists’ Invitations 1965-1985, published in 2019. Analyzing the various archives we encountered over all these years, we realized that very often the boundary between an invitation to an exhibition and a work of art was almost imperceptible. Conceptual and Minimal Art, but also Pop Art and Fluxus with their countless artists, often used this communication practice as a means of dissemination, specifically thinking up an artistic idea to be printed on a postcard, a card or an invitation card. Since the end of the 1950s, with the beginnings of proto-conceptual art, this wonderful practice began, which has fascinated so many people from Yves Klein to Lucio Fontana, Andy Warhol to Gerhard Richter, Marcel Broodthaers to Sol Lewitt.

Would you like to tell us about an episode in which the search for a book, or the attempt to buy it, turned out to be almost a feat?

A great anecdote concerns the purchase of one of the most sought-after artist’s books, River Avon book by Richard Long, a book made up of sheets of paper dipped in the mud of the River Avon and dried in the sun. In 2015 we presented a stand at Artissima Torino for the first time, dedicated exclusively to Land Art documents and works, among which was Long’s book. My father exhibited it without any real intention of selling it, but a dear friend of ours who is a collector, as avid and passionate as we are, convinced him to sell it to him. My father allowed himself to be tempted, hoping in his heart to find it, but this did not happen for a long time. Four years later, in 2019, a copy appeared on the counter of an English bookseller in FLAT Turin and my father, without a second thought, rushed to buy it. Unfortunately, it had already been sold. So my mother and I, unbeknownst to him, started looking for a copy to make up for the disappointment and dissatisfaction that the sale of the book and the consequent void in the collection had left in my father. The opportunity came last summer, scrolling through the pages of Instagram, I casually found a photograph of the book posted by an English collector, I immediately rushed to contact him and after a long and “onerous” negotiation I convinced him to sell it to me, we hid it from my father until the day of his birthday to celebrate it with a truly unexpected gift.

Within your family, does each of you have specific interests in any artist or historical moment? What catalogues have marked your personal research?

From the very beginning, my uncle’s and my father’s interests evolved within fairly defined margins, making it easy to divide up everyone’s tasks. While my father devoted himself to art, my uncle pursued counterculture themes.

Today, the boundaries have remained defined, with the only difference that the group was joined first by my mother, who has always dealt with women artists and gastronomic culture, and then by me, who was strongly influenced by my father’s interests and moved my research to the field of contemporary artists’ books.

The catalogues that have most characterized the path of each of us are also those in which the work has been carried out by the individual member, and I am referring in particular to those dedicated to D’Annunzio’s venture in Fiume, to Italian Counterculture I am referring in particular to those on D’Annunzio’s Impresa fiumica, Italian Counterculture, Body Art and Marcel Broodthaers edited by my uncle Paolo, or those on Ettore Sottsass, Superstudio, Radical Design, Keith Haring, Sol Lewitt, Land Art and Arte Povera edited by my father, or the two “women artists” catalogues produced after many years of research by my mother; I myself recently had the pleasure of completing my first real work for the studio by editing the catalogue of an exhibition held last November in our studio dedicated to Hanne Darboven 1968-1980.

A bibliographic studio can also be considered as an archive and as such poses fundamental questions related to the arrangement in lists and catalogues, filing and, no less important, the search for volumes. What is your modus operandi with regard to these aspects of the work?

Searching, filing and listing and cataloguing are all equally important to us, and over the years my father and uncle have tried to define them according to precise patterns. Filing is the longest and most laborious part of the work, and our bibliographic records must be as precise and detailed as possible, and understandable even to those who are not particularly well versed in the subject. The arrangement in lists and catalogues is dictated by the sum of the previous procedures, nothing is left to chance, the order is established on the basis of the type of research carried out.

A brick wall that leaves an open door where the horizon is showing a half moon high in the sky. This is what is represented in your historic logo. What does it stand for?

The logo was designed by my father Bruno many years ago, to lightly express the desire to look for “a way out of ignorance” in that wall cracked towards the horizon with a half-moon, perhaps the same one represented in the paintings of Magritte and Chagall or sung in the verses of Marinetti and Montale. We discussed changing it many times with my uncle Paolo, but we never reached a good compromise.

Thanks to the collaboration with Galleria 17.2, which specializes in artists’ books, posters, photographs and invitations and is directed by Alessandra Faita, your bibliographic studio has the opportunity to show its collection to a wider public. One of our interests as a young archive and curatorial board is how to exhibit these objects. How do you construct your exhibition projects? Do you ever feel that the fruition of these exhibitions is a bit limiting? Have you ever thought of new practices and forms to facilitate the use of these objects, without risking to damage them?

Since 24 December 2019, the gallery has been moved to Gussago in the attic of our studio where the 17.2 apartment was born. We no longer have a showcase in the city but we still organize various exhibitions in our space. My father Bruno has curated various exhibitions and texts dedicated to documentation in Europe, especially in Spain, in Madrid at the Fundacion March for the exhibition Avanguardia aplicada and in Santander in 2014 for the exhibition Sol Lewitt. El concepto como arte in which the entire printed production of the American artist was collected. Artist’s books, posters, invitations and ephemera were arranged in showcases and hung on the walls. It was a unique exhibition and the layout was very classical. Of course, the way in which books are displayed can be limited by their very nature, which in my opinion does not fit well with the fact that they are on display. But I think it is important, in terms of display, to conceive of them as objects, differentiating them from the concept of the classic book, so that a less knowledgeable public can appreciate them in the same way as works of art.