The Vertigo of Collecting

Archive Actualized #3: a conversation with Giuseppe Garrera

Archive Actualized is a series of interviews, a format that aims at exploring some of the Italian and international artist’s books archives and bibliographic studios. The term “actualized” is meant to highlight the potentiality of these locations, as keepsakes of circularity in a system, a (political) space with no specific rules, waiting to be activated. For the third issue, Replica has met musicologist, art historian and collector Giuseppe Garrera.

REPLICA: Books, documents and texts are often the most complex materials to exhibit, and this is particularly due to their fragility. This aspect leads most of the time to opt for a partial and unsatisfactory exhibition: trapped under display cases, it is difficult to fully enjoy them. Given your experience as curator of several exhibition projects, what is your opinion on this issue? Is it possible to find more satisfactory ways of fruition?

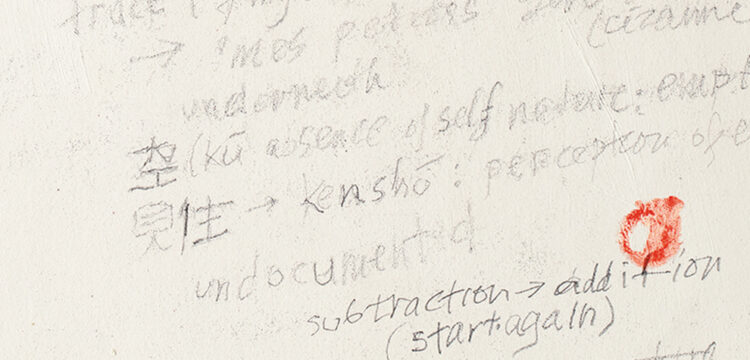

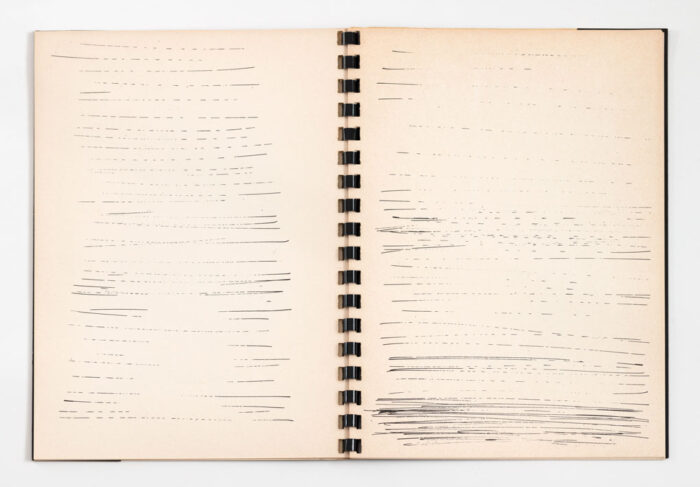

Giuseppe Garrera: Actually, on closer inspection, this is a problem that rarely arises. Books, documents, paper materials, ephemera I mostly deal with, from the sixties and seventies, have a constitutive character: they are highly visual, that is, the artist tends to convert every part of the artefact into a vision (so that it can be seen rather than read). They are visionary productions and the best declination for many of these materials is precisely that of understanding them as objects, sculptures, adventures for the eyes within all the innovative and poetic layouts and graphic solutions. They work well for display, because they come from the world of visual thought. Munari taught us that first of all a book is an object to be seen and, whose—not secondary—function can also be just being seen and never opened nor read. Its presence entails a discourse on form and visual ideas. For what will unfortunately turn out to be his last book, Bruce Chatwin demanded and obtained a specific paper, a specific layout and measure of margins and spacing, and a certain choice of page fonts that his book, like a Sufi text, could even be contemplated as a typographic incarnation. I would recommend anyone to take a look at this book Utz, by Chatwin, which then, not surprisingly, is a book—perhaps the best book—dedicated to collecting and the vertigo of collecting.

The books, documents, publications and ephemeral materials should be felt and understood in their first—if not primary—instance as apparitions or epiphanies. I would say above all tampering and experiments with the traditional and conventional forms of paper: it is a question of dreaming of the book, of a catalogue, of the invitation, of the page of a magazine, of the printed word, rather than merely showing them.

Your rich and heterogeneous collection could one day become a real archive. In your opinion, could an archive from a collection be considered a work of art?

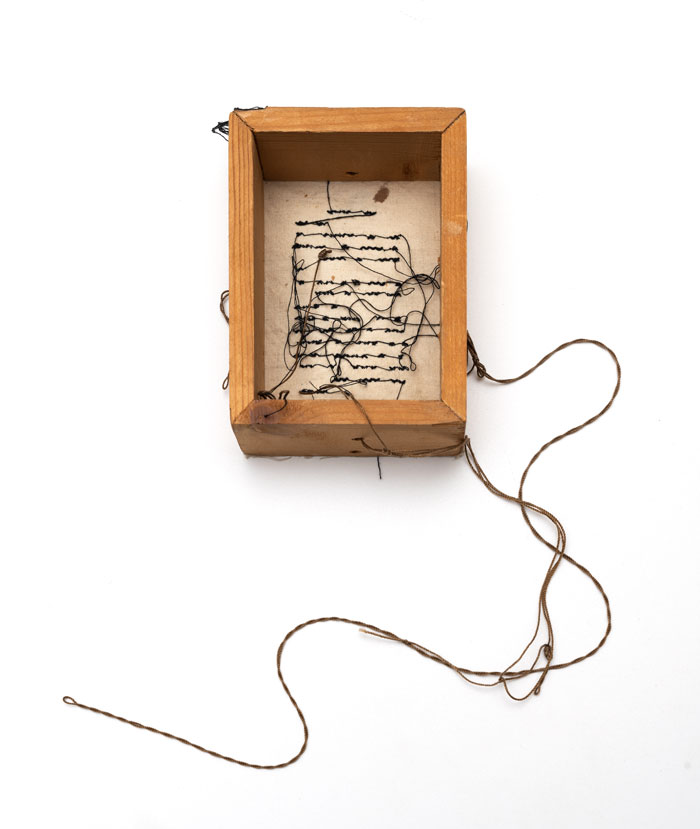

The archive of a collector would seem to be a narrative of rescues, discoveries, passions, hunts, mirages, acute fevers. Firstly, it is about restoring a past time and setting up a cabinet of curiosities where current and actual thoughts, events, hopes and fears are embodied in idols, fetishes and traces. Rarely does an archive resulting from a collection become a work or totality and this is because it soon overflows, gets lost, sinks into secondary areas and rooms, digs caves where it piles up treasures that no longer make sense, fills basements with piles of memories and with the anarchy of pain, it erects temples and altars at every corner, but above all it seems to want to escape from something, to lose its tracks, to always try new ways of escape, there is no longer a centre and it becomes impossible to know in the end where it lies. There is a point after which a collection becomes a pure catastrophe and takes on the monstrous character of a rubbish dump where it is no longer possible to distinguish the treasure from the rubbish heap. The heirs, by selling, and the museums or private individuals, by buying, can put order and selection back into this bewilderment, make a discourse about it, cultivate regret, but no more than that.

You recently started a collaboration with the MACRO in Rome within the public programme called Agora. It is a series of meetings where you are asked to describe and narrate some works through documents in your collection. The first meeting was devoted to a work by Gino De Dominicis. What do you think about this method inaugurated by the museum to bring archives to life? As a teacher and at the same time collector, how do you approach your students in relation to the textbook readings that are often made of works of art or artists? What story do you tell them?

Many of the best art research projects of the second half of the twentieth century have humanly bound themselves to time and dispersion, have refused the protection or imprisonment of the museum or gallery, have taken place outside, have flooded streets or cellars, have avoided guarding themselves or saving themselves as a product, have chased drifts and sought derailments: they have been reality. Many of the most memorable works and operations of contemporary art are on the run. For these experiences, only the archive can bear witness, collect and transmit: the archive material preserves the work so that it doesn’t’ give up its freedom and dissolution. To save, to snatch these moments from the lion’s mouth (disasters, destruction, failure to act, neglect, elusiveness), and to bear witness to and recover the integrity of creation is a task of the museum: everything must be saved, that is, the work of an artist or movement must be understood as a dispersed sparkle present in every manifestation, testimony, fragment. The museum must aspire to the whole time of creation as a revolutionary time, and to a practice of celebration, and therefore learn to consider the work never separated from the world and from life, and the documents as the only possibility to access it.

There is a point in Jean-André Fieschi’s 1966 interview with Pasolini where Pasolini, suddenly, after he has been talking about his books and verses after an hour answering questions, confesses that all speeches are pre-textual, that is, they must be, they are alibis for saying something else, and that one must learn to speak outside of average, social and cultural habits, and strive by speaking (whether of a film, a poem, a painting, an action) to make one always feel, in some way, a great joy and a great pain towards life.

Last October, we started #BUONCOMPLEANNOBRUNO, a project dedicated to Bruno Munari. We know that several books and unpublished artworks are also part of your collection. Would you like to offer us a glimpse? Would you also like to tell us an anecdote about the first edition of the spelling book?

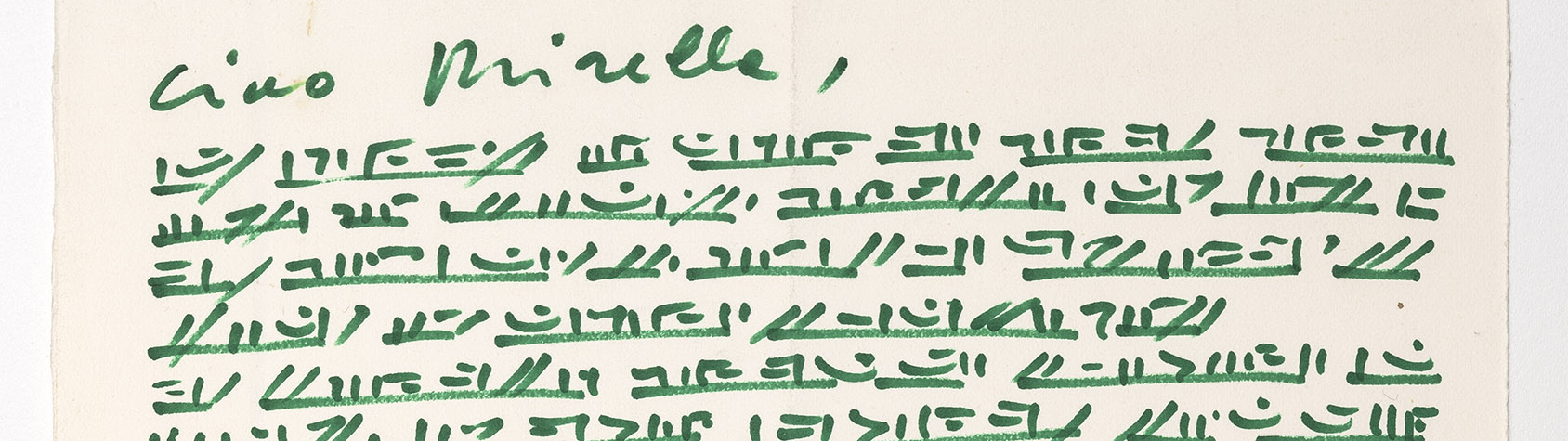

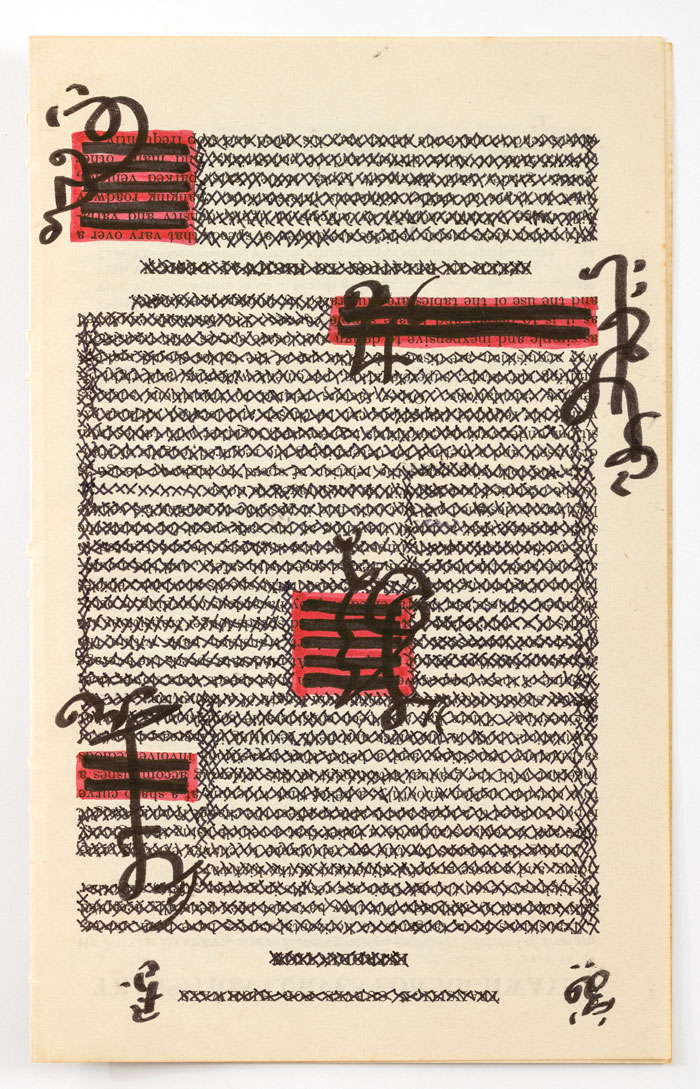

Yes, in my collection I had the 1942 Einaudi spelling book by Munari, which I found and owned once. A very rare book because I presume that Einaudi had to make it disappear from circulation at some point, if not destroy it, and this due to the fact that, out of complacency and tragic topicality, the letter H was accompanied by the image of a Hitler, a Teutonic knight with a hooked banner. There had been two directives or suggestions from above, the first being the idea and celebration of Hitler for the letter H, and the second, innocuous and indeed benign, to accompany the letter S with the image of an ostrich, the heraldic symbol of the publisher. I have been collecting Munari for a long time, and for me, he is first and foremost a reparation of childhood (the imagination of the child’s “treasure” always lurks in collecting), so games and toys and oddities and inventions. Apart from his books and his covers or editorial projects (the covers for RCA’s 33rpm and 45rpm records are magnificent), I have collected above all the most fragile, light, domestic things, capable of celebrating the feriality of the days: the travel sculptures, the xerocopies, the advertisements, the postcards, the interventions hidden in magazines and in improbable and lost publications.

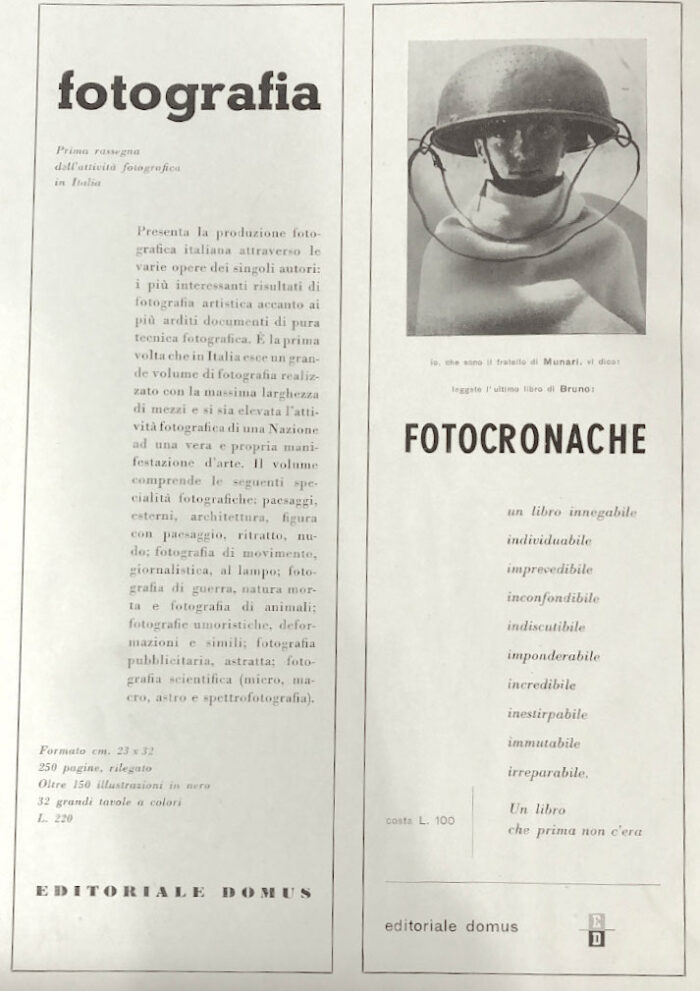

In Il sillabario dei fili, edited by Emma Rabutti, Editoriale Domus Milan, 1944, I have just come across an extraordinary advertisement by Bruno Munari for his book Fotocronache, which had just come out. The advertisement is not only wonderfully crazy but also mocks all the rhetorical assumptions of the publication and of a military, masculine and daring Italy.

An alleged brother of the author shows up with a photo of himself in an unreliable and crazy way and wants to sponsor the purchase of his brother Bruno Munari’s “unmissable” and “amazing” book. Of course, looking at those who advertise and praise that book, one understands that both the book and the author and brother of the author come from the asylum, and from a world dominated by madness, fantasy, desire to play and invent, and that only the madmen around will be able to buy that product. The effigy with a giant colander for a helmet, a proud and fearless look, recalls the unrivalled Don Quixote and all the dreaming “knights” who never stop fantasising and fighting against all reason, common sense and calculation. The author’s brother is the twin, the double, the doppelganger, the best part of Munari, who has come to the rescue to boost sales, because the book is—and it really is—spectacular. For me, this is an extraordinary example of “discovery”.

Part of your collection was built up during your exploratory walks through the historic Porta Portese flea market. Recognising important editions absolutely requires a great deal of investigation. Where did it all start? How do you go about selecting the materials you come across?

The Porta Portese market is an outdoor exhibition in the streets of Rome, about the disasters of time and dynasties: clearances, emptying out entire interiors of houses overturned on the counters, libraries of enthusiasts—brothers in fever—thrown away for neglect, haste, revenge or contempt of the heirs (many liquidations are “settlements” of relatives). A fantastic and impudent spectacle of the innards of lives and passions, in which to rummage and browse, in the most catastrophic moment for things, when having lost their owner they are no longer recognised, but thrown away and degraded to the pavement and at the mercy of the profane. It is here that the collector, wandering around, becomes a saviour, able to recognise in the rubbish the treasure, the glimmer of a golden thread, what was missing from his dream (at Porta Portese I found entire archives, rare materials, endless treasures). In the beginning, for me the stalls and markets, even before the adventures of mourning and descent into hell, were the urgency of the student to buy books and procure, with little, infinite readings, and seek new paths, urged on by chance, and precisely, as I said at the beginning, by the lure or enchantment produced by covers, papers, formats, diversity, strangeness, unrecognisable characters that testify to some kind of rebellion or intolerance (at the beginning, my passion for poetry and for its outcast and abandoned editorial condition led me to encounter an extraordinary production with masterpieces of craftsmanship and copying and poverty, and the adventure of courageous, non-aligned, experimental publishing houses up to the subversive production of visual and concrete poetry).

I would say that one of the origins of collecting is precisely the fruit of this greed and doggedness by virtue of scarcity and a feeling of social injustice with respect to one’s own desires: one becomes an astute, shrewd, attentive reader and hunter. Money, or rather the lack of money, is, together with hatred of the world, one of the fantastic forces of youth. The promiscuity of money and poetry produces idols, treasures, rarity, splendour, revenge, redemption, at all times contact with the mythical treasure of childhood, and titles of nobility.

As a passionate bibliophile, you have had the opportunity to visit various bibliographic studios and professionals such as Giorgio Maffei’s, to whom we have dedicated an interview in this column. How would you describe these places? Do you think it would be useful to write their history?

With Giorgio Maffei there was a great deal of contact, and in fact I passed Munari’s spelling book of 1942 on to him: like two children, we made an exchange (he had been looking for it for some time and had alerted me to look for it and find it, promising me wonders as a reward). Maffei’s research was exemplary because it stemmed from the correct consideration that much is still unknown, that so many adventures in art are waiting to be illuminated: the 20th century is practically all unknown to us, and will require more excavation work than that carried out by archaeologists or tomb-robbers: landslides, ideological fires, carelessness and hasty abandonment, stances taken, carelessness, amnesia and flooding have made it an area in need of reclamation and restoration, exploratory missions and drilling. The work of bibliographic studies in this direction has been and is fundamental, but it is not by chance that I have used the term archaeologists and tombaroli (grave robbers) for all the good and murky things that I inevitably mean in an activity that also has an economic and mercantile thrust and in which one has to get one’s hands dirty, enter houses in an unctuous manner, open cupboards, unseal drawers, rummage under beds, extort promises, appease widows, forgive sons and daughters, and deceive heirs (let’s never forget this). The world of collecting is marvellously full of shady areas and abuses, of swindlers and tricksters, duped and deceived, and Jesuitical practices. But from necessity and criminal actions come acumen and care, and at the same time one of the characteristics I have found in the best bibliographical studies is that the owners end up hopelessly compromised with the passion for collecting and research, and often also operate as infected and incurable. I would say that one of the most fascinating and childlike aspects of this world is its familiarity and indulgence with piracy.

What criteria do you use to introduce a new element in your collection, is there a common thread linking the works, books and documents you have collected?

I like to delude myself that in the collection the pieces that enter are the missing pieces, we are now at a point where it is the collection that dictates the law and gets out of hand: it suggests or imposes entrances, new paths, indicates needs, serious absences, produces visions and mirages of other horizons. Above all, by virtue of that force Giordano Bruno included within the natural magic of things, generally speaking an object or an author as soon as it enters the collection saves and pulls friends along with it, marks affinities, and aspires to several important genealogies. The collection produces itself, follows its own purposes or needs, and therefore for us this simply means keeping up with it, and I never know where I will find myself looking. At the moment it is hard for me to see where it will end up, not least because it must be born in mind, in my own personal case, that I have a twin brother, who is a collector like me and who, like me, with the same enthusiasm, on the other side is digging basements and piling up stuff. I wonder how this den or kingdom or tomb of ours will turn out in the end. Certainly, collecting the most extreme, non-aligned, disobedient and radical research in art, I can imagine that a red thread that can still hold the collection together at the moment, but there are many temptations and distractions, is that of radicality and of models that attest to resistance to the mortification of life, against all the obligatory paths. A run towards the sea, Deligny would say, and so that justice may be done to us who flee.