What Are You Feeling?

Nora Turato first solo show at Sprüth Magers, Berlin

NOT YOUR USUAL SELF? is the first solo show of visual artist and performer Nora Turato (*1991, Zagreb) at Sprüth Magers in Berlin. The work presented in the exhibition, focused on the use of 1980s vector graphics, stimulates the audience’s emotional and personal sphere. Through a complex visual-textual layering, Turato’s work deconstructs the passive language of advertising, inviting the audience to actively interact with subjective existential questions.

I recently decided to resign from my job. I needed a break from everyone and everything: my friends, my family and my colleagues, and all those familiar places that have defined my life up until now. Thinking about it now, I can clearly see that this break from the trajectory of my life was a form of self-inflicted pain—a step forward, a recovery that has proved to be longer, more profound, and painful than I had anticipated. I’m extremely privileged to talk about “leaving in order to heal” at a time when the Palestinian people are enduring apartheid and genocide, facing devastating repercussions that will forever change their land, future generations, culture, and who we are as human beings. The crisis is everywhere—fleeting across our screen for a few seconds before being swallowed up again by the algorithm, which feeds us with what we really need: more crap.

When I arrived in Berlin, in early November, the world was falling apart and I was lost, trying to understand this new city I was living in. “NOT YOUR USUAL SELF?”, the title of Nora Turato’s solo show at Sprüth Magers, was a guiding voice from a place I hadn’t figured out yet, prompting me to wonder whether I had, in fact, become someone other than my usual self.

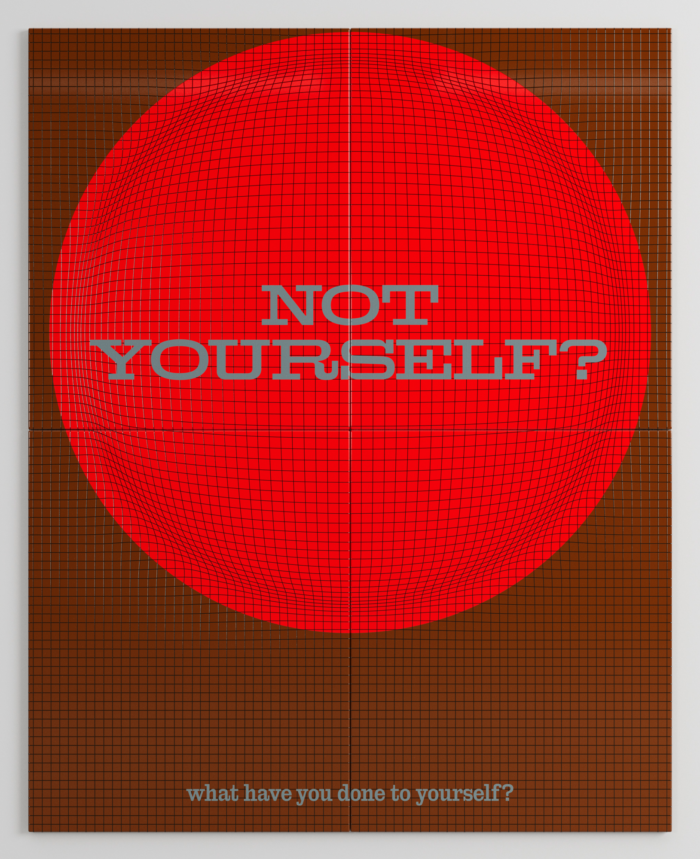

Nora Turato, not yourself? what have you done to yourself?, 2023. © Nora Turato. Courtesy the artist, LambdaLambdaLambda, Galerie Gregor Staiger and Sprüth Magers.

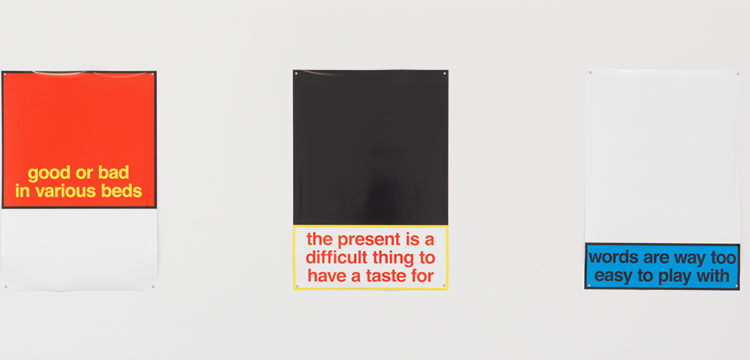

Located on the second floor of the gallery building, the exhibition welcomed me with a site-specific installation, an expansive black and blue writing on the wall proclaiming “UNDEFINE YOURSELF” accompanied by five enamel panels featuring a custom typeface. Despite their layered construction and polished appearance resembling mass-produced marketing materials, the enamel works are intricate constructions pushing the technical limits of both material and printmaking. Baked at 800 degrees multiple times, each layer was painted and fired separately, resulting in a glossy, industrial painting.

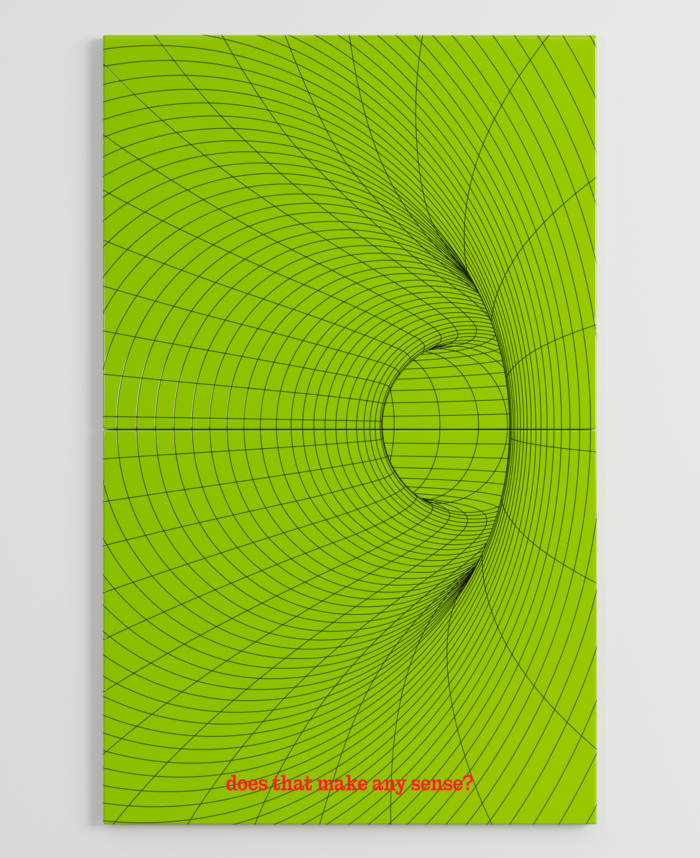

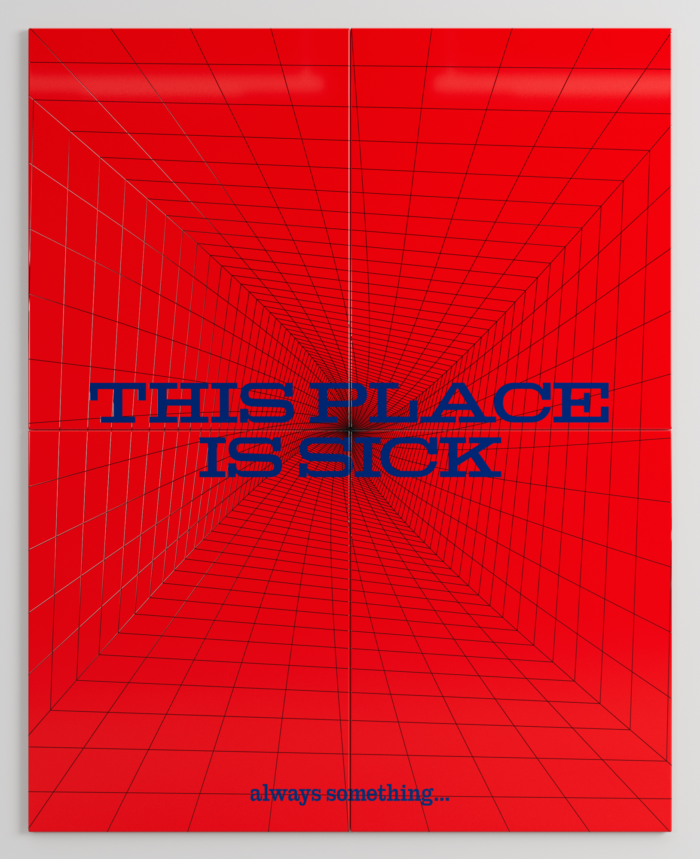

Turato’s body of work reimagines the concept of the vector graphics of the 1980s, depicting tunnels with a central vanishing point or round shapes in prime colors, which take the visitors down a rabbit hole. These graphic elements act as seismographs of contemporary social concerns, reminiscent of advertising posters challenging us to question ourselves. The first panel provocatively aske, “Not Yourself? What have you done to yourself?”

In our daily lives, we keep moving forward without really paying attention to where we actually are and what we truly want for ourselves. In our everyday lives, we often move forward without much consideration for our true desires and current position. Turato delves into these fundamental questions of human existence, resonating with Heidegger’s concept of Dasein, a German term pertaining to existence. This term stems from da-sein, which denotes “being-there” or “there-being”, thereby conjoining both verbs—“to be” and “to exist”. But how can we navigate the use of these two verbs amidst the swirling chaos of contemporary living conditions that have been transformed into a hyper-capitalist production of existence and visibility? When the state of Being disintegrates into a crisis of its very presence? In his work La Fine del Mondo (1977), Italian scholar and ethnologist Ernesto De Martino speaks of “crisis of presence”, referring to the breakdown of the objective signs that give meaning to language, perception and relationships, ultimately to our very existence. From this perspective, “dasein”, or rather “presence”, the state in which perception is relaxed and our being exists as a biological fact, as a solid living body, constantly clashes with the progression of time and life which brings us closer to death, revealing a disintegration of the familiar terrain with devastating psycho-perceptual repercussions.

Turato’s works fit into this complex condition of the collapse of presence as analyzed by De Martino, but from a different perspective. The overproduction of capital and the proliferation of biopolitical manipulation strategies have created a system where individuals must engage in self-monitoring, self-evaluation, and improving their production tools. These measures have become necessary for individuals to categorize their contribution to the economy, both within corporations and the broader social system.

“There is a profound incompatibility of anything resembling reverie with the priorities of efficiency, functionality, and speed.” (Crary 2013, 88) says Jonathan Crary in 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep. This mechanism leads to a constant increase in competitive behaviors, generating as a physiological result, no longer an “accumulation” of productive capital but a degenerative departure from a de-responsibilized of its own condition. Sleeping, daydreaming or just take-care of ourselves isn’t possible. This process results in a constant escalation of competitive behavior, leading to a physiologically harmful outcome of decreased accumulation of productive capital and a negative impact on individual well-being. This hinders essential self-care activities like sleeping and daydreaming, while also linking well-being solely to capital production and requisite individual performance, ultimately defeating the purpose of this endeavor. From this perspective, the employee no longer satisfies their desires, or rather their primary needs linked to physical well-being, but those of the capitalized system. This makes them part of an impossible competition between demand, desire and production. The person therefore becomes disconnected from their own desires and the notion of well-being, leading to the abandonment of subjectivity in favor of dissociation.

By combining bold and eye-catching questions, Turato evokes the overbearing tone of self-help culture with a lowercase (possibly inner) voice, offering tools for decolonizing us from the aforementioned cognitive capitalism’s education.

Historically, self-help practices have been associated with the privileged class, especially second-wave feminism’s emphasis on the liberation of the white, heterosexual bodies. Actually, this issue has been manipulated by neoliberalism to enforce specific labor and social policies. In fact, after World War II, workers have internalized this concept as a means of overcoming production limitations, by assuming responsibility for the success of the entire “potential production,” ultimately leading to the adoption of self-medication practices and antidepressants. The incursion of this idea into the social, productive, and labor contexts is not only a consequence of neoliberal labor policies. It also constitutes a distortion in media language, which increasingly privileges the use of subliminal messages aimed at enhancing individuals’ subjective “productive potential” and the consequent “empowerment”. From this perspective, Nora Turato’s works tries to trigger a de-empowerment of the self, against the concept of “magical voluntarism” proposed by psychoanalyst David Smail, according to which, within the social hierarchy each individual can and must conquer their own sanity with their own self-management skills. The success or failure of this process determines the degree of potentiality and value each of us has in our society.

Like dizzying tunnels, Turato’s panels invite us to reconsider self-help from a decolonized perspective to biocapital’s production. As a result, self-help is no longer seen as a competitive self-production of well-being, but as a practice of self-orientation, that aims at recovering one’s own position, including one’s feelings, origins, culture and personal sphere far from the concept of educational “training”, which on the contrary includes the concept of production in its own meaning. These are factors that affect the life of each individual. They cannot be generalized or ignored in such a complex biopolitical network of production. Nora Turato’s works present themselves as a criminal act to the production-system, as advertising-like messages that speak directly to us, giving us access to our stages of recovery, our vulnerabilities and our life paths, ultimately revealing where the subliminal message around us is leading us: is this really what we want?

Three giant windows break the flow of the panels, reminding me, reminding us all where we are, and that the world out there is real.