What Are We Trying to Find?

Fragmentary tales inspired by the works of Motus and Agrupación Señor Serrano

“What’s your first recollection of a smell?”*

As a body inhabiting the urban space of the post-capitalist era, I sometimes get lost. Disorientation seeps in, breaking the straight lines of thought and movement.

I welcome these moments as an instinctive rebellion against the geometric order the ruling system enforces. My wanderings through space manifest as circles, waves, sinusoids, braids. I would describe my idea of research with these same images. Freed from the romantic sense of passionate fury, as well as from the capitalist notion of “preliminary phase” (necessary for achieving a goal), research can finally take shape as an act of conscious and joyful failure that makes sense in and of itself, as a practice.

The following text is an interlaced narrative of two performances, Frankenstein (History of Hate) by Motus and Historia del amor by Agrupatión Señor Serrano, both presented during the latest edition of the Festival delle Colline Torinesi in Turin, between October and November 2025. The aim is not merely descriptive but unfolds through impressions, flashes, and hypotheses.

A woman in a baroque, petroleum-colored dress walks breathlessly along a stony, dusty path on a mountain overhanging the sea. She doesn’t seem to be heading anywhere; indeed, the path itself seems to end in nothing. It feels more like a tiny space, caught between land and water. The sequence lasts only a few seconds before looping infinitely, refusing closure. The woman’s search remains unknowable. Perhaps she had only perceived that language itself rests, silently, within matter—a word inside a stone.

Frankenstein (History of Hate), the second episode of the diptych that Motus dedicated to Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel, opens with a video projection, a sort of “performed film” as the directors call it in the project’s presentation text. The woman’s body—hypothetically Margaret/Mary Walton/Wollstonecraft-Seville/Shelley (Alexia Sarantopoulou)—will never appear on stage. It remains a kind of ghostly presence, a premonition. From a time long past, and not quite human, she pronounces a prophecy that concerns the future now rushing toward us. She becomes the embodiment of what Derrida defines as the trace. A past that has never been present, whose future resists any reproduction of presence. Every appearance carries henceforth the resonance of this absence.

A drone circles above the audience. Its hum—that low, nervous vibration—is the sound of destruction. It is, more specifically, the sound of war and genocide. “Horror is a part of life we hope not to witness too often,” writes Teju Cole in Black Paper: Writing in a Dark Time—and yet, I would add, it is alarmingly easy to grow accustomed to it.

Motus’s show overflows with words, images, and objects that provoke anxiety and terror—sensations too familiar to be dismissed as merely dystopian. In a scene of the projected movie, Dr. Frankenstein (Silvia Calderoni) traverses the desolate Calabrian landscape, scattered with unfinished concrete structures. She drags a suitcase so light it must be empty. Why she does so, we don’t know. A beautiful and pitiful human being, who cries and screams with a force almost unbearable for such a fragile body. She seems to say: at all costs, one must be heard.

They are not voices from the future. Nor are they echoes of the past. Frankenstein (History of Hate) collapses temporalities and, in exposing the urgencies of the present, it compels us to reconsider what we mean by utopia. Through the visual and emotional vocabulary of disaster—the same that populates our daily screens—Motus invokes what Ernst Bloch named concrete utopias. Not idle fantasies, but the active hope of a collective, or, as José Esteban Muñoz proposes, of “a solitary visionary who dreams alone for everyone.” To dream today feels almost out of place. Yet perhaps it means only this: to exist. In a time of systemic collapse, existence itself becomes the dream’s most radical form.

A postcard shows a lavish exotic resort, complete with mock huts and vast swimming pools, beside a brutalist skyscraper from the seventies. All around lies the desert. It’s time to let go of the idea that aridity and abundance are opposites—if anything, they are deeply, unexpectedly linked.

Along the scorched paths where Dr. Frankenstein runs, breathless, the creature (Enrico Casagrande) appears and vanishes. Transplanted from an unknown space-time, the creature moves through the scrub with unsteady steps. Its movement is constrained. Fear grips it; its body is shrouded in thick layers of black cloth—a gear that seems suited for survival on a poisoned world. And it becomes obvious, Dr. Frankenstein and the creature are searching for each other, but their encounter will never come, at least not in life.

This quest, at times almost a hunt, unfolds in a post-apocalyptic echo of the El Dorado love resort. Originally designed for consumption and for generating services and well-being (the very things capitalism thrives on), it ends up abandoned, lacking anyone to use it. Potentially reclaimable by human and non-human beings who cannot expose themselves to the contemporary regime of visibility, the monsters find their way into this space.

The performer looks straight at the audience and says: “I’m alone, in pitch darkness. There is absolutely nothing around me. There is no longer any jungle or golden promise.”

Words are flat, uncolored—neither angry nor sorrowful—simply expressing the intent to remain and inhabit an utterly hostile place. Behind her, the silhouette of a growing mass of debris, packed into countless black plastic bags, becomes sharper and sharper.

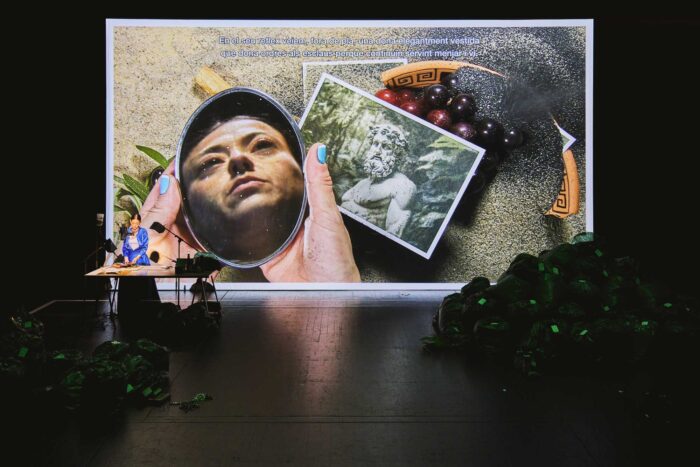

In a setting that feels partly a laboratory (Frankenstein’s shadow slowly creeping in) and partly a junkyard, Agrupatión Señor Serrano’s Historia del amor takes shape. We can never quite tell whether the objects abandoned onstage are trash or clues—unexpected remnants that stubbornly cling to the present, standing there demanding to be seen.

In this surreal environment, the performer (Anna Pérez Moya) gathers together bits of stories, never reaching the end of any: myths from ancient Greece intermingle with pop icons and with biographical snippets (though whose biography remains a mystery).

One might call it an unfinished performance, one that reveals nothing—not even a true love story. It samples the most famous ones (like Romeo and Juliet), touches them lightly, and moves on before we can feel anything. Thinking it over, we cannot find a single epistemological justification for this unruly progression. The political frame that had marked Agrupatión Señor Serrano’s early-2000s work has become less explicit. Only the title provides a clue: we are disappointed because we wanted to sit down and listen to the history of love. In retrospect, it was clear that this expectation could not be fulfilled. We feel the same frustration that, presumably, explorers chasing El Dorado must have felt. That postcard shown in the first minutes of the performance was a foreshadowing, a silent warning: here, you will find nothing.

Note: we should privilege the generative force of research over the seductive beauty of a story that’s already been told.

Telling history is a presumptuous act—a gesture of power. Postcolonial theory reminds us that every dominant historical account conceals countless others, omitted because someone decided from which perspective it was “proper” to look.

In Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route, Saidiya Hartman warns of the danger of recounting the past, recognizing that it can be a threat here and now. Her method—both memoir and part documentary essay—is a reflection on how history might live. Let it be collective. Let it keep discordant voices, the uncertain traces where memory bleeds into fiction. Accept that history will never be a clean chronology, only fragments scattered with opaque stains.

Despite sharing the word History in their titles, these works adhere to this very methodology in their dramaturgical structure and scenic construction. Stories of hatred and love [the first act of Motus’ work is called Frankenstein (History of Love)] convey the screams and whispers of collective voices. There is no epistemological, prophetic, or bibliographic claim. Instead, fragments of debris and detritus, eternally close to decay, are put together without expecting any inherent meaning to arise. Meaning is a product of modern thought. Always following cause and effect, meaning dries out everything it touches.

At the center remain the bodies, threading their way through darkness, hiding to avoid being blinded by the light. Perhaps the very belief that light allows better vision is itself a consequence of modernization—the era when a switch can command illumination. Spending enough time in darkness, one “discovers” that the body adjusts, and even the skin becomes a vessel for endless imagination.

Historia del amor and Frankenstein (History of Hate), though distinct in language and form, both manipulate history—scrambling timelines, exchanging voices, and folding one era into another. While their titles suggest universality, the works themselves expose the instability of the divide between personal and universal history. It is a deliberately political stance.

Epilogue

We used to believe that family photos were private objects. Almost secret things, to be kept locked away in worm-eaten drawers. That was a mistake. In the final moments of the show, the performer snaps a Polaroid of the audience. The dramaturgy offers no explanation. I guess the act basically meant: this is what we should call history.