Wear a Mask, Become Invisible

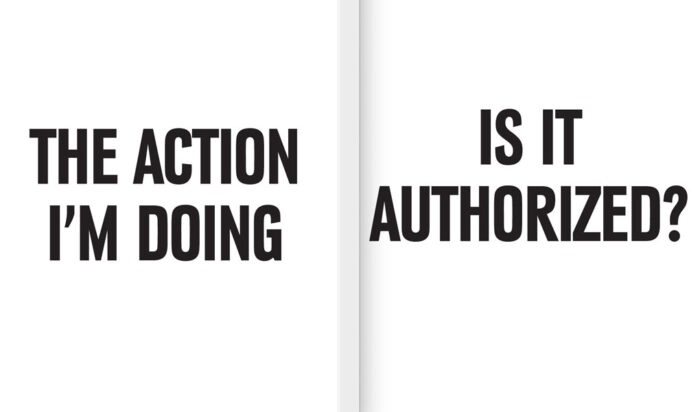

How to make an illegal action interact with a content that coincides with it?

Sara Leghissa’s practice has always been investigating the space in between the inside and outside, the street and the stage, the public and the political, the legal and the illegal. The current situation that deprived theaters, museums and festivals of their audience, has somehow created another “in between”—namely the digital and the real space, for whatever that means. Here, she reflects on the concept of mimicry and what it means to take up a certain space to make things visible.

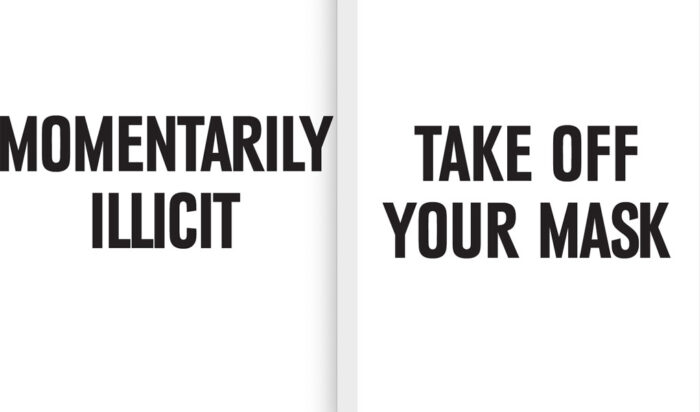

Milan, two years ago. During a session of Nobody’s Indiscipline, an independent performing arts platform for the exchange of practices, one of our guests, Kama (Carlo Fusani), an artist and a good friend, suggested the practice of sticking banners on the walls of our city. In describing the proposal, he offered instructions: first and foremost, it’s an illegal practice so in carrying it out, we should be very careful not to be seen. That single notion is already incandescent in its own, all the more when added to the dynamics of the construction of a practice. In my artistic practice I have always had an ambiguous relationship in regards to law. I often use the public space as a stage and a source of inspiration in the process of creation, I have always had to seek out plausible excuses in order to justify my work to the cops. Moreover, in order to explore the public space, some conventional codes of “theatre” have to be adopted, but they are taken “outside”, into a territory where there is no proper regulation. These, therefore, have always been invented, created, or renegotiated, depending on the need, the audience, the narrative. This piece is built around the question: how to make an illegal action interact with a content that coincides with it?

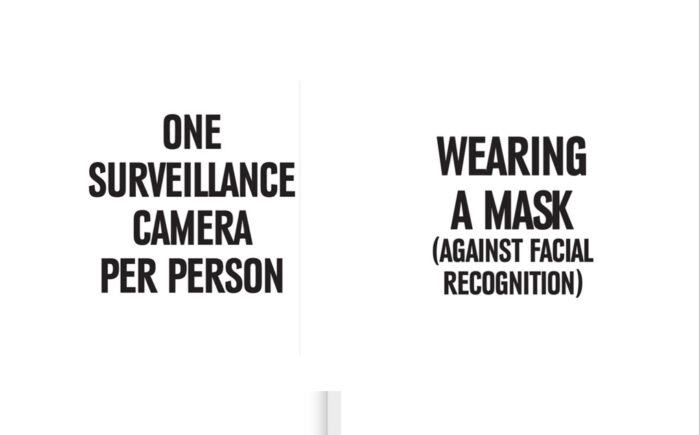

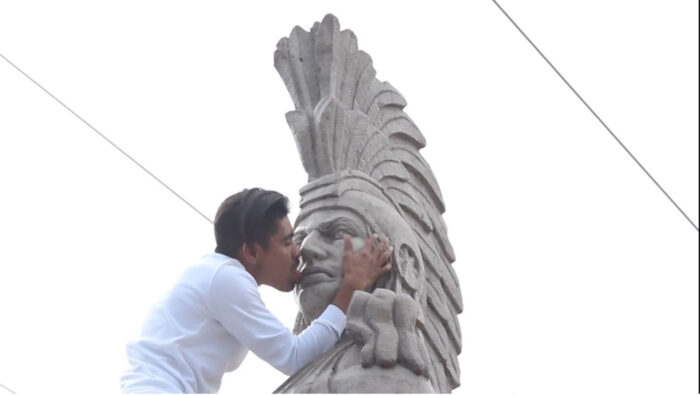

Over the course of a year, by listening to people who live the topic of illegality the hard way, and who had to necessarily incorporate forms of illegality to survive in their daily lives, my research moved towards the exploration of illegality as a widespread, subtle, semi-visible practice. I could also observe that the rule of law in general is a fluid concept, which shifts and changes depending on the historical moment, the privilege that we embody, our place in the world. I broadened the research to explore what is called the “mimetic use of law”, i.e. those practices that use the law to violate the law, where there exists a plain denial of human rights. We could mention as examples, the practice of marrying somebody to acquire citizenship in another country, or, in countries that prohibit abortion, the practice of organizing trips to international waters in order to perform an abortion. What is the strength of an illegal act? Why is it used as a practice of resistance and fight? “Illegal gestures make those in power visible—to quote the words of Madu (Maddalena Fragnito), friend, artist and activist, meticulously transcribed in a notebook—they make power visible. Illegality has a symbolic and material power, because it makes power visible and manifest. It goes against the rigidity and the steadiness of power, discussing things that always seemed to be in a certain way. Consider the action carried out on Montanelli’s sculpture: pink paint was poured over his statue, over his image. The visibility that illegality brings about has been made explicit, making this visibility a work of art.”

In the video performance Te amo, the Mexican artist Javier Ocampo illegally climbs statues representing patriarchal and colonial power figures in the history of Western culture and kisses them passionately, making them visible.

The idea of giving visibility to illegality through an operation that is in itself illegal begins to take shape. Further inspiration comes from the works of some street writers, whose practice and action have always inspired mine, because of the accessibility and the ecology of resources they imply.

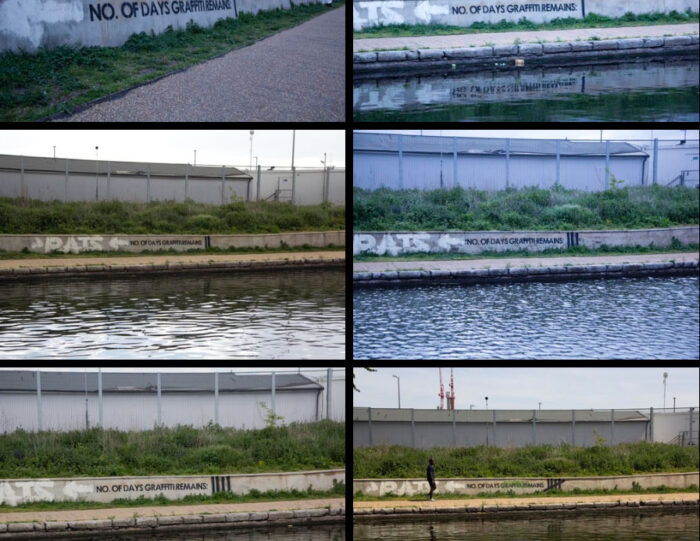

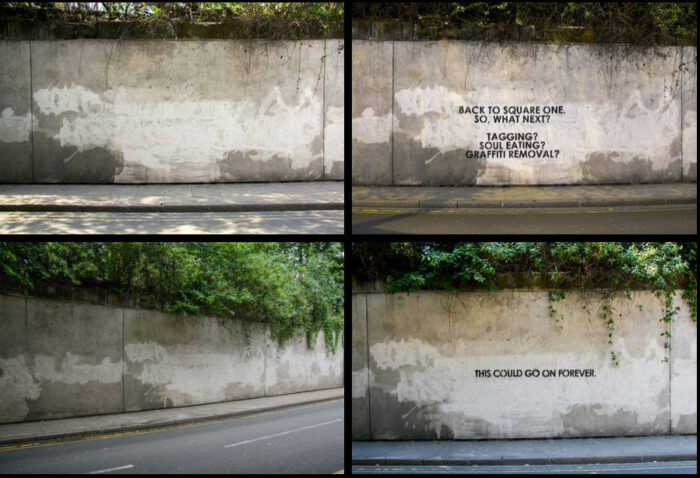

The power of public writing, which comes through spreading a message in public space, is precisely that of being so exposed and so ephemeral. The choice of space; the rapidity in which it manifests and continues over time; the continuous dialogue with the precariousness and unpredictability of the street; these are all forms of renegotiation of this code. Like in a performance, the illegal action of a writer exists in the “now” moment. It manifests itself in all its power because it makes sense in this moment, and then it disappears. Or it remains, in which case it re-signifies, depending on the landscape that changes around it. Its accessibility coincides with the duration of its permanence. There is an artist, Mobstr, who has turned this “time-lapse” into his work. He has materially “marked” the duration of his work in the public space, making it coincide with the work itself, and sometimes opening up conversations and questions directly with those who interact with him, in this case making the conversation a work in itself.

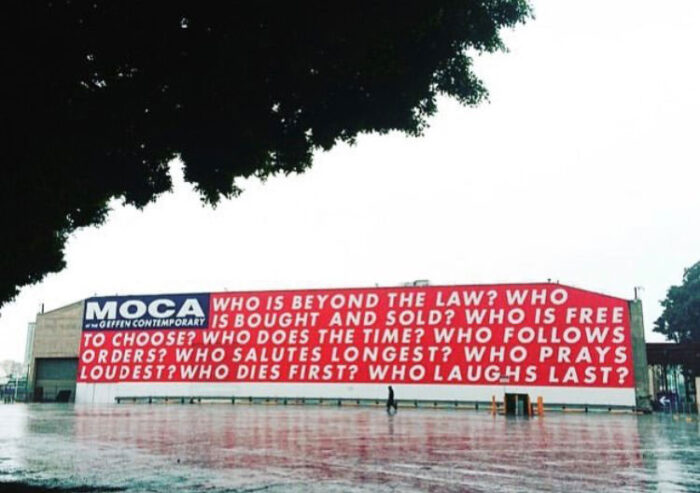

In this sense, there are works by artists that have greatly inspired the construction of my work. My mind goes to Barbara Kruger, Alfredo Jaar, Jenny Holzer, Escif, Mobstr, Revs, who, through completely different devices and formats, bring words into the public space to ignite images, intuitions, states of mind, unexpected drifts, into those who come across them. And, as in the performance, their narration is in the hands of the viewer.

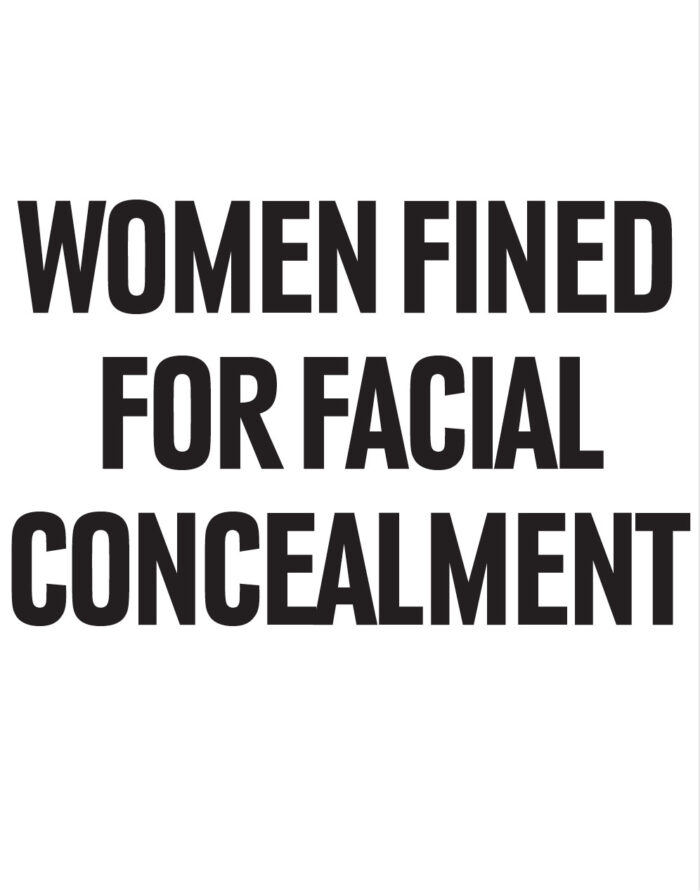

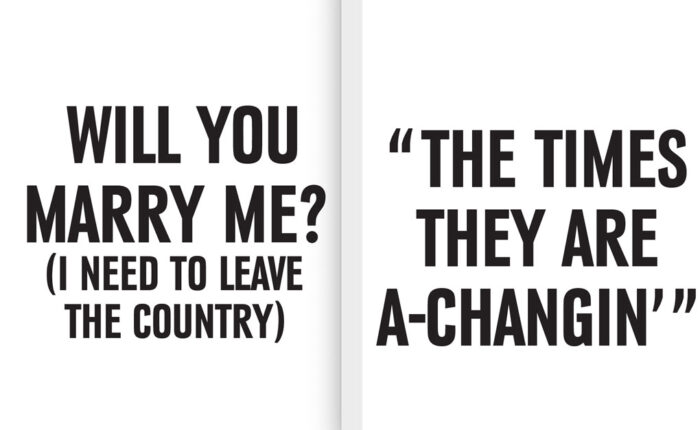

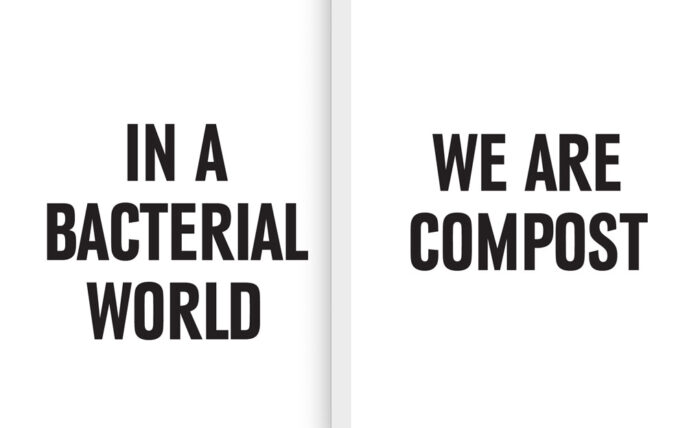

The desire to use words in posters/banners was born, so as to place statements that hint to advertising slogans, but shifting the meaning to something closer to the research. With this material, through other illegal actions, night and day, and thanks to the collaboration of Marzia Dalfini, Tomas Gonzalez, Catalina Insignares and Kama, and of people who are willing to exchange their experiences and explore these issues, even their words, which is the content of the work, the project is composed and declined in a very specific way, depending on the contexts and encounters, often undermining the direction of the research and shifting meanings and perspectives.

What I call “public space” can be called as such if I am in Palestine?

“Here there is no public space—Yara, a girl and a friend I met during a residency in Ramallah, tells me.—Actually, theoretically speaking, I don’t even exist for Israel as a legal subject. If we refer to Israel, if we consider the law, their law, I am not legal, as a Palestinian, therefore as a person.”

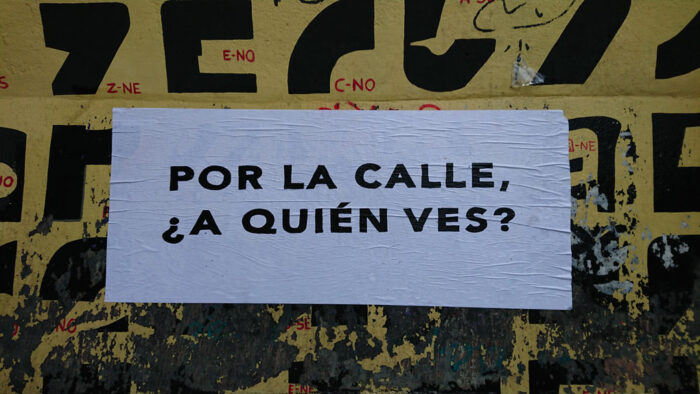

During a workshop I held in the Lavapiès neighborhood of Madrid, together with some students from the Carlos III University, a long meeting took place with a community of people from the Fundacion 26 de Diciembre, a space created with the aim of making LGBTQIA+ elderly people more visible. On the foundation’s website we read: “On 26 December 1978, the Spanish Council of Ministers ratified the amendment of Law 16/1970 on Danger and Social Rehabilitation. This law, approved by the Franco regime on 5 August 1970, punished any person considered socially dangerous, including people from the LGBTQIA+ community. Under the imposition of this norm, many LGBTQIA+ comrades were wrongfully imprisoned, tortured, mistreated, persecuted, harassed or subjected to shock treatment, simply because they had a sexual orientation or a sexual or gender identity that did not fit in with what the regime wanted. This date—26 December 1978—is marked in the history of the LGBTQIA+ community in Spain, which continues its fight for equal rights. (…) One day, while having a few days off in Gran Canaria, Federico Armenteros sees an older gay man walking towards the sea leaning on his walker, and feels pain when he notices the invisibility of the old LGBTQIA+: ‘Where are they?’. Question that marks the beginning of the development of the 26th December Foundation.” Lavapiès is still a working-class neighborhood, despite being in the centre of Madrid. It has been re-populated by a recent wave of immigrants from Northern and Central Africa. In order to control them, police patrols have been implemented and they constantly monitor the neighborhood. My proposal during the workshop was to stick banners to the walls of the neighborhood, but it seemed very difficult: the patrol vehicles were constantly passing by. We organized ourselves in such a way that one part of the group acted as a lookout on every corner, while others illegally sticked the posters that have been prepared. Each poster is a small manifesto. Statements, based on interviews with people from the LGBTQIA+ community of the Fundacion 26 de Diciembre, and questions regarding life in the neighborhood and the personal experiences of the students. After a few hours on the street, we realized that the action, although illegal, could be carried out with ease: our presence did not draw the attention of the patrols, who have other targets. We, as white Europeans, are not cause of concern. This consideration fuels reflection on the difference between taking illegal action in public space as a privileged subject, and experiencing it on one’s own body, as a marginalized subject.

It is on this occasion that Pepe (Pepe Serrano), a young person who took part in the workshop, made up a large poster and sticked it up in an extremely visible place in the neighborhood. The poster states: “OUT IN THE STREET, WHO ARE YOU LOOKING AT?”

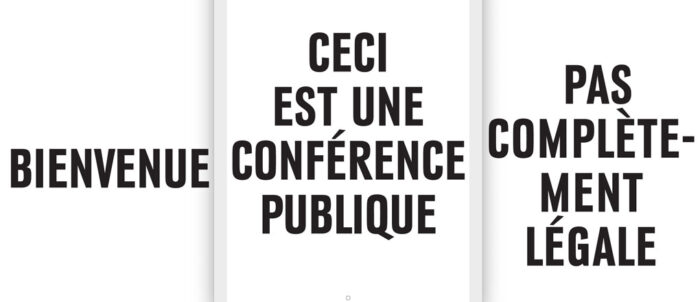

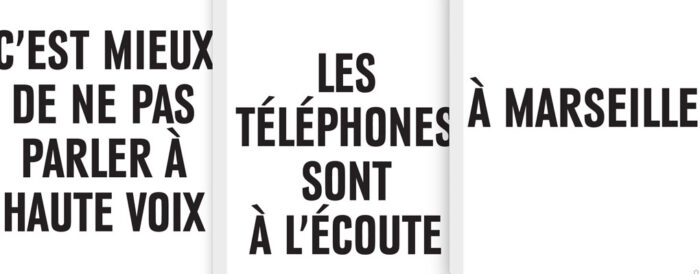

We developed this text, drawing on the situations we encountered. The text is shaped by experience, and constantly adapting to the context. In December 2019 the text was released publicly in Marseille, in the form of a public space performance entitled FAKE UNIFORMS (ACTING INVISIBLY UNDER EVERYONE’S EYES). The performance, advertised as a public lecture, invited the public to go to a specific place, close to some advertising panels. Some banners were stuck for about 30 minutes: 70 posters, 3 statements at a time, are stuck to the panels, continuously re-signifying the content of the previous text, while the person who’s hanging them is wearing a professional uniform.

The lecture seems to have reached an almost definitive form, and awaits its official public presentation, which should take place in Milan in April 2020. Obviously, this speech, as it was envisioned, will never take place. On March the 8th 2020, Milan goes into lockdown, a measure that seems to last one month, but will in fact extend until May, changing every possible perspective. This shift, the transformation of the perception of the body and its potential, both in public and private space, the different perception of the possible and the impossible, the contagious fear of a militarized atmosphere and the feeling of being authorized to spy on, control and report on transgressions, restrictions and increasingly stringent prohibitions, reopen like a gash what was supposed to be a final version of a text that is, however, non-definitive and transitory by definition. Since then, the lecture has been rewritten again and again, in relation to the current context, addressing an audience that, in the meantime, has experienced exactly those principles we are talking about. The initial text, adapted to the new context, takes on a new meaning, more identifiable, closer to the reader. The work, through a principle of meta-representation, takes upon itself that same question of potentially exploring the edge of legality. To the question I am asked: “Is transcending the boundaries between legal and illegal an authorized device of representation?”—I would say: “Not always. Sometimes. Allow space for doubt.” The fact that going to the theatre has become an illegal action these days is part of the reflection. The action is its content, and invites reflection on the impossibility of labelling, defining once and for all, establishing a pattern.