To Yikakou

Nadia Beugré returns to Short Theatre with her new piece “Épique! (pour Yikakou)”

Nadia Beugré‘s new work Épique! (pour Yikakou) delves into her homeland, taking her back to her childhood, to the village of Yikakou. An impossible return to a secret and imaginary village, another lost Macondo in Ivory Coast, the village of her grandmothers, the village where she grew up. The piece will premiere at La Pelanda on Spetember 5 and 6, at Short Theatre 2025.

Short Theatre is a multidisciplinary festival active in Rome since 2006. Short Theatre engages with the changing landscape of national and international contemporary performing arts, through a layered program made of performances, installations, talks, lectures, workshops, concerts and DJ sets. The festival facilitates an open environment for research and experimentation to develop new forms of production and circulation of arts-related knowledge, offering established and emerging artists a space and a time to meet, to get to know each other, and exchange.

This edition of Short Theatre is co-directed by Silvia Bottiroli, Silvia Calderoni, Ilenia Caleo and Michele Di Stefano in the attempt of practicing collective curation as an artistic and political gesture and of nourishing the possibilities of experience that the festival may offer to artists, visitors and communities.

The piece you are going to perform in Rome is titled Épique! (pour Yikakou) is dedicated to the “secret, fantastic village” of Yikakou. How do you take your native land on stage? From the village to empires, from your grandmother’s Gbahihonon to Soundiata Keita, what is the lineage between these characters?

Nadia Beugré: I have grown and built myself up with these female figures, those who had the courage to step outside the role and the tiny corner that their families and society had assigned them.

Here, I was not interested in Soundiata Keita, but in Dô Kamissa, the woman who transformed herself into a buffalo to ravage her brother’s lands. A powerful woman, an oracle, she forced the king to marry the ugliest woman in the village and predicted the birth of Soundiata and the epic that has spanned centuries. However, she is a figure who is often forgotten, and I wanted to rediscover her. I wanted to know who she was, what she looked like in very concrete terms. So, I planned to travel to Mali to meet griots and listen to ancestral stories…

Then I had a “visitation” and a voice said to me, “But who are you?”

Salimata Diabate, who accompanied me in this process but will not be able to be on stage in Rome due to administrative issues in France, shared with me this Mandinka proverb which says that if birds need to fly, they still need the tree. They need to land, to return to the source.

And this trip to Mali became a journey to my father’s village, Yikakou, where I had not returned since my teenage years, the village of my grandfather and my great-great-grandmother, Gbahihonon, the one who gave me my name. Because between Nadia and Beugré, there is Gbahihonon, literally, “The woman who says what she sees.”

Gbahihonon was also a powerful woman who predicted the fate of newborns and protected the community from both physical and mystical attacks. I returned to the village for the first time to experience the weight of this name, Gbahihonon, to discover who I am.

We made two research trips to Yikakou in July 2024 and January 2025. I wanted to invite my entire team to visit this village that no longer exists, to listen with me to the stories of those who still live in the surrounding area.

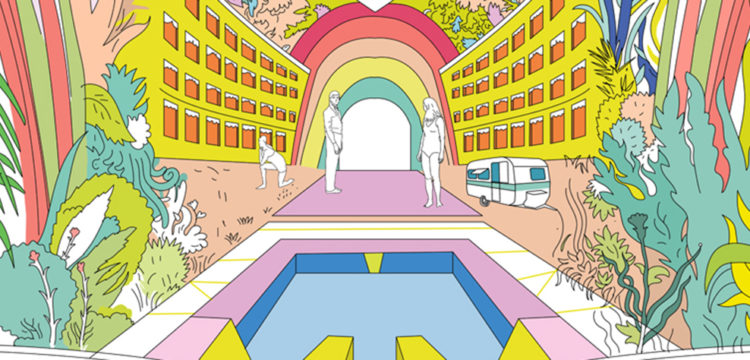

Ideally, I would have liked to invite the audience to Yikakou, to transform this vanished village, now empty and covered by forest, into a stage. So I worked with Jean-Christophe Lanquetin, the set designer, to bring Yikakou to the stage. The stage became a territory, both in space and time.

You will be accompanied by a griot and by a singer, both very necessary, I would say, for the world of today. How are they bearing all the different voices and stories? How have you worked on the music and on the narrative along with the choreography?

Although I conceived Épique! pour Yikakou as a solo piece, I wanted this solo to be accompanied, to be a story told by several voices, voices that would welcome me and respond to me. I imagined a griot, an old woman whose body and memory would guide this return to the land of my childhood. I had even identified an Ivorian griot from a village in a video, thin as a twig, both fragile and powerful, but we never managed to find her.

I had known Salimata for a long time and admired her music; she is one of the few women to play the balafon in Burkina Faso, but I wanted to deconstruct this Mandinka music, and even for her to be able to deconstruct, dismantle, and reassemble her instrument on stage, which we ultimately abandoned. There were also drums that were discarded. Then I met Charlotte, who sings zouglou, a very socially engaged Ivorian musical style that deals with everyday life and social realities, and she became my griot.

For the ahoko, it was the same thing. I wanted to be able to use each part of the instrument separately and repurpose it: the stick, the scraper, the hollowed-out shell, the amplifier, which becomes a whistle, for example. We also worked on the percussive body, of course… and the dialogue and resonances between our bodies. Sound and dance are intertwined, they are one. And I even felt like I was becoming a musician!

The original music by Lucas Nicot, with whom I had already collaborated on L’homme rare (2020), came late. I asked him to work from the voice of my older sister Hélène, from a message she left on my WhatsApp when she heard I was returning to the village. Lucas followed the process and composed almost live… So, throughout the process we journeyed together through dance, song, sound, and space.

In an interview you said places are born out of confusion, you work with the unpredictable, “shrifter”—what made this Épique?

As with all my creations, when I began this journey, I had no idea where it would take me. I always work based on my intuition; I am visited, I proceed by vision, by image…

I remain open, attentive, vigilant to what may arise, to the unforeseen, the unexpected. I give importance to what is usually overlooked, ignored, what has no value for most people. It is this attentiveness that guides my journey.

I am greatly inspired by these young people in Africa, these magicians who must invent the conditions for their survival every day, those on whom no one bets, neither society, nor even less so the authorities.

When I returned to Yikakou, the village had disappeared, the people had left, the forest had swallowed up the houses, the streets, the graves, because there, the dead were buried in plots, as close as possible to the living. So we cut, sliced, and cleared the ground to at least find the graves, my father’s and my grandfather’s, and after a few hours, they appeared. I took care of them, cleaned them with tissues, because that was all I had on me.

This trip was also frightening because, as city teenagers, we had grown up with the idea that we shouldn’t return to the village, that there were witches and spirits waiting for us there. But when I found this grave, strangely enough, I lay down on my grandparents’ grave, something that is never done in our cultures. Lying down on that grave was like freeing myself from the fear that had accompanied me for so long. Something was finally resolved…