The Responsibility Of A Cultural Institution

The Venice Biennale must meet its own history

Following the open letter published by the ANGA collective, “an international group of artists, curators, writers, and cultural workers who have come together to call for the exclusion of Israel at the Venice Biennale, ” I feel the urgency to offer a wider historical context, in order to understand how far and in which way the institution could act to stay within the borders provided by its statute, and where its institutional responsibility begins. Here, I would like to share what I have studied over the past twenty years, hoping that this text can become a tool for imagining new possibilities.

There is a more than 100 years long history that the International Art Exhibition has never truly inhabited, and such an institution cannot move forward without acknowledging its history. The quintessential “unstable institution” has placed the historical archive at its center (ASAC) as a “permanent area of research and cultural production.” [1] Nonetheless, I would like to begin by giving a symptomatic example of the overall lack of awareness of its own history and heritage.

During the year of the pandemic that forced the postponement of the 59th edition, the International Art Exhibition decided to set up the show The Disquieted Muses. When La Biennale di Venezia meets history (2020) in the Central Pavilion. Made more for social media than for an actual public, given the limited mobility of that historical moment, the exhibition was accompanied by a glossy, full-bodied catalog full of illustrations, but with poor scientific value when compared, for example, to Archiv in Motion, the book produced by documenta for its 50th anniversary. Obtained through an obvious investment in staging, the scenic show-up was an example of fetishization of discourse-producing documents, a definitely problematic choice when considering that none of those was sufficiently deepened nor contextualized. [2] As the institution showcases its documents, one would assume that this would entail a historical revision to affirm (or not) a positioning, but already from the title, that was instead completely absent: the institution was meant to “face History” in general, rather than“its own history”. A quite ambitious endeavor considering that, for this specific institution, History itself is produced simply because of its longevity. To give one example: the elegant totem set up in the Galileo Chini Hall, right in the center of the exhibition space, presented a series of cinegiornali produced by the Istituto Luce, showing with no philological order images of WW2 aerial bombings along with international movie stars at the first edition of the Venice International Film Festival, in the luxury of the Lido. This was the incipit of the exhibition. But who founded the Istituto Luce? [3] Who was the president of the institution at that time? Who decided to establish a film festival in the luxury hotel on the Lido that he owned? What is the institution telling us in the face of its fascist years (we are aware of the fact that this all happened in the fascist years, aren’t we?)? Is the totem somehow celebrating that historical period as if it were a golden one for the institution?

To highlight the nescience toward its own history, and perhaps History in general, I would like to mention another fact. When visiting the “Transparency” section on the International Art Exhibition Italian website, one finds a document signed by Paolo Baratta, undated but attributable to the end of his presidential term. The document is titled The National Participations in the Venice Biennale, which Baratta describes as “an original formula by which countries freely and autonomously organize the presence of their artistic novelties in Venice. This formula constitutes one of the keys to the Biennale’s prestige and international fame.” Then he goes on saying that the exponential rise of requests for international participation he had witnessed during his presidency is “an extraordinary phenomenon (…) fascinating. For each participating country, small tutelary deities of individual Participations have been created that are working with incredible enthusiasm,” finally calling the annual convention of international representatives “a small UN.” Despite his long presidency (2008-2020), Baratta seems unaware that, already in 1948, in all newspapers the International Art Exhibition was widely referred to as the “Geneva of the Arts” or the “UN of the Arts”, as it was heroically reopening after the wartime interruption, and the UN had just been established, while the world was reemerging from the tragedy of WW2, and Italy from two decades of dictatorship. For the president of the Biennale to compare a cultural institution to the UN in 2020, as the ultimate achievement of a Russellian ideal, [4] sounds as troubling as ever, but that is exactly what the institution continues to boast of without questioning the matter of its own internal borders and exclusivity (yes, precisely like the UN), while it continues to describe itself as a “meeting place for peoples.” The president’s enthusiasm for defining the phenomenon of national pavilions with cute adjectives is both worrying and dangerous, although one could give the benefit of the doubt, and blame his corporate vision or background that would make him consider everything about art either fascinating or innocent. In the same text he adds “in various International agreements with Italy, the possibility of being able to organize a Biennale pavilion is mentioned as an important aspect of the agreement.” Alright, does that even sound like a “detail” or a “fascinating thing”?

When one studies the history of national pavilions in depth, it becomes clear and obvious even to an art historian—not to an expert in geopolitics—that the way in which one country gets the permission to obtain a national pavilion instead of another is always, always, justified by the Italian government’s economic or political interest. On the institutional website, it is possible to trace who the properties of each national pavilion pertain to.

In this text I will attempt to browse through institutional roles and responsibilities, providing a “brief” recollection of when and how the International Art Exhibition became the cultural arm of Italian political propaganda in the International arena. The question I would always ask when entering the territory of the International Art Exhibition is: who is talking to me? [5]

First and foremost I would like to make my own positioning explicit: I am an art historian and my reasoning is more based on documents than on personal opinions, and on a reflection resulting from the study of historical facts, evidence and laws. [6]

National Participations

Who are the Countries (the institution uses capital letters everywhere) that can aspire to get a “National Participation”? “Countries recognized as independent states by the Italian government.”

The ownership of the National Participations is consequent upon the official invitation of the International Art Exhibition “to exhibit inside their own pavilions in the area of the Giardini di Castello and those hosted by La Biennale for a long-term period in the Arsenale (…) the participation in the Exhibition will also be extended to those Countries without a pavilion that have officially applied to participate in the Biennale, and for which La Biennale has confirmed the invitation.” Today the invitation to the various eligible nations has become a pro forma, as for all intents and purposes the entry “Venice Biennale” is part of the state budgets of almost all participating states, many of which have established over time special agencies dependent on ministries of culture, and devoted exclusively to the management and organization of the Venetian exhibition. If before it was the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs who was sending out the official invitation to the ambassadors in Rome, nowadays that is carried out directly by the institution.

Following the current regulation, it is stipulated that “the Governmental Authority (Minister of Culture, Minister of Foreign Affairs, or competent Minister for Cultural Affairs) of the Country will appoint a Commissioner who will have to belong to the Governmental Authority or to the delegated Public Institution representing the Country. As representative and direct expression of the Governmental Authority of the Country the Commissioner will (…) supervise the project (…) and be responsible for the exhibition in the Country’s own pavilion, in agreement with La Biennale and in compliance with the Exhibition’s cultural and organizational standards.”

Like embassies that enjoy the immunities codified in the 1961 Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations, inside the national pavilions the principle of extraterritoriality applies as a fundamental principle of international law. This type of autonomy goes back to its origins, when, in 1907, the Secretary General of the International Art Exhibition Antonio Fradeletto proposed that foreign artists would be housed in special national pavilions to be built within the borders of the Giardini, in order to overcome the incessant controversy on the part of Italian artists who felt that they had little exhibition space because of the overwhelming presence of “foreign artists”. [7] Originally, the Palazzo delle Esposizioni (now the Central Pavilion) was designed to accommodate Italian and foreign artists invited by the International Commission, although Italian artists still showed up divided by regional schools, and the exhibition, established as “International”, was increasingly becoming a space with a hypertrophic Italian presence. [8] From the very beginning, the countries wishing to obtain a national pavilion had to come to an agreement with the City of Venice, the owner of the ground, which had the power to approve the plans submitted by foreign countries, authorizing the granting of the ground on which the pavilions would be built. Once the permission was obtained, the country could decide whether to build its own pavilion right away, at its own expense, and with architects of its own choosing, or whether to entrust the project to the City of Venice, and purchase it at a later date. The agreement and arrangements for the purchase or lease of the pavilion were made independently from the International Art Exhibition. In both cases, once the agreement was made, the pavilion would become the property of the nation, which would bear all maintenance and set-up costs. In this way, the International Art Exhibition gained numerous advantages because, other than additional space for Italian artists in the Palazzo delle Esposizioni, it relieved itself from all the expenses of countries’ participation with the added benefit of securing a constant international presence over time. The advantage for the foreign country was a complete autonomy from the International Art Exhibition and the acquisition of all the privileges of having its own international showcase that the Venetian stage guaranteed. By statute today it is the board of directors that has the “power” to “maintain relations with states participating in the events of the Culture Society.” [9] Foreign countries may “be invited to refer” or “latch on” to the general direction, but they retain complete autonomy of choice over which the International Art Exhibition cannot interfere. This is why only the commissioners or the curator of the national pavilion can, according to his or her own conscience, decide whether to withdraw from an edition out of his or her own responsibility and sense of ethics, but the International Art Exhibition by statute cannot interfere, just as it happens between governments and the embassies present in their national territories.

We saw an example of this curatorial responsibility on Feb. 28, 2022 when Raimundas Malašauskas, curator of the exhibition for the Russian pavilion, resigned from his position, stating “I cannot go forward to work on our project as a result of Russia’s military invasion and bombing of Ukraine.” On the same day the institution embodied by president Roberto Cicutto (appointed in 2020 by Culture Minister Dario Franceschini, Democratic Party), published a statement on the official website: “La Biennale di Venezia has been informed of the decision by the curator and artists of the Pavilion of the Russian Federation who have resigned from their positions, thereby canceling the participation in the 59th International Art Exhibition. La Biennale expresses its complete solidarity for this noble act of courage and stands beside the motivations that have led to this decision…La Biennale remains a place where peoples meet in art and culture, and condemns all those who use violence to prevent dialogue and peace.” The International Art Exhibition speaks out in solidarity with Malašauskas’ “noble act of courage”, and declaring it is “supportive” and reaffirms itself as a space “where peoples meet in art and culture,” condemning “all those who use violence to prevent dialogue and peace,” although the goal of that statement is to officially validate the cancellation of the Russian participation. What caused the pavilion to remain closed for that edition was the curator’s own responsibility supported by the chosen artists. [10] We, art workers, left him alone while we took part in the exhibition as if nothing had happened.

The International Art Exhibition actually took a stand on April 15, 2022 when it declared its “immediate reaction” in the face of Russian aggression, announcing Piazza Ucraina “an open-air installation (…) to confirm once again the collaboration between our Institution and the Ukrainian ones” wishing “that this initiative will help raise awareness in the world against the war and all that comes with it.” A space is allocated to Ukraine for an installation in the heart of the Giardini to give “a voice to artists and the art community of Ukraine as well as other countries in solidarity (…) and to create a space for debate, conversation and support to Ukrainian culture.” Whilst over the years Ukraine had sporadically taken part in past editions in outdoor venues, this time it makes its official entrance in 2022, invited by the institution itself. On the occasion of the 60th International Art Exhibition, Ukraine appears among the National Participations and will be hosted in a pavilion at the Arsenal. We will come back to this point, but what I would like to point out is that as much as the decision corresponds to the foreign policy alignment of the Italian government, it still shows what the institution can do simply by its positioning.

Collateral Events

Then there are the Collateral Events. “Collateral Events include original exhibitions and/or installations, in public or private buildings or in public areas, of original works and—as exceptions—initiatives such as conferences or symposiums, organized in the city of Venice and concurrent with the 60th International Art Exhibition. Collateral Events must be promoted and organized by non-profit public or private institutions operating directly and primarily in the field of art, with the exclusion of both central and local territorial public institutions and administrations.” Collateral Events are “selected and acknowledged by La Biennale as an integral and specific section of the Exhibition”, to obtain this qualification, the project “must be formally approved by the Curator [what used to be called the artistic director of the edition], whose decision is final and irrevocable, in terms of the level of quality and scientific significance; only those projects will be taken into consideration that might represent a specific and substantial enrichment of the research and the themes of the Exhibition of the Curator, hence with exclusion of generic group exhibitions.” Since the Collateral Event formula was established in 2005, many cultural identities not recognized as independent states by the Italian government—such as Taiwan, Hong Kong, Scotland or Wales, to name only the oldest examples—have applied to enter the official program of the International Art Exhibition. After passing the selection, Collateral Events must pay the right to use the logo (€25,000) that allows inclusion in the official program of the event.

I’d like to give an example: in 1948 Israel officially requested the Biennale to participate with its own national pavilion within the Giardini, in the same year that it was proclaimed an independent state by the UN. In 1951, the Biennale approved the request and the Venice City Council granted the ground next to the US pavilion, [11] according to the official history, the adjacency seems coincidental, and dictated by “saturation of spaces between existing buildings.” Again the official history adds that in the immediate postwar period, the requests for the construction of national pavilions were numerous, and it was therefore “essential” that nations had “quick decision-making and ready financial means.” In 1952 Israel inaugurated its national pavilion designed by “pioneer Zionist” architect Zeev Rechter (1899-1960). It seems unnecessary to me to dive into the reasons why some countries long-recognized by the Italian government such as Argentina (will obtain it in 2011 in the Arsenale), Brazil (1964, Giardini), Chile (2009, Arsenale), Mexico (in various locations since 2007 and recently in the Arsenale) or Uruguay (1960, Giardini) on the waiting list to have a national pavilion for years, have seen themselves undermined by the newly formed state of Israel.

If the institution gave a fast track to a young state at the expense of others, and invited Ukraine in 2022 as a gesture of solidarity, the same cannot be done with Palestine since it is not recognized as an independent state. By regulation, however, it appears that it is the “Biennial Curator” who is responsible for approving (or not) the Collateral Events (his/her “decision is final and irrevocable”). So it is his responsibility, when an edition that takes place under the pressure of a genocide unfolding before our eyes, and under the chairmanship of Pietrangelo Buttafuoco (appointed in October 2023 by the Minister of Culture of the Meloni government, Fratelli d’Italia), decided to exclude the proposal of the Palestine Museum US (Connecticut, USA). To date, the museum has brought the Palestinian voice to the Biennale’s international stage, and had already participated as a Collateral Event in 2022. If a parameter is the “enrichment of the research and the themes of the Exhibition of the Curator”, the project presented by the Palestine Museum entitled Strangers in their Homeland, seemed to perfectly adhere to it. The question that arises then is what kind of confidentiality agreement, and what kind of decision-making autonomy the curator has when he or she decides to sign the contract to run the International Art Exhibition?

In 2002, when the artistic director of the 50th edition Francesco Bonami proposed to invite Palestine to participate, he was promptly accused of anti-Semitism by the local press. Faced with the strict regulation restraints we have seen, Bonami decided to invite Sandi Hilal, a Palestinian doctoral student at the University of Gorizia, and Italian researcher at the IUAV University of Venice Alessandro Petti, to present Stateless Nation, not an actual pavilion, but an installation on Palestinian identity in the form of 10 oversized passports scattered throughout the Giardini. Hilal and Petti chose passports because “Palestinians, whose movement in Israel and the occupied territories is often restricted, ‘are absolutely obsessed with travel documents of all kinds; we can’t afford not to be’” and Hilal adds “If you consider that more than half of all Palestinians are living outside of Palestine, then what is Palestine right now? Is it simply a limited geographic area? If Palestinians are dispersed all over the world, and if we think of the Biennale as a metaphor for the world, then Palestinians should be dispersed all over the Biennale. I would have represented the Palestinians this way even if he had asked us specifically to design a pavilion. For us, this is the Palestinian pavilion.” Giant passports suggest to Bonami a broader critique: “We live now in the midst of this huge conflict between the rise of globalization, where in some significant ways there are no borders and no limitations,” he said, “and at the same time we see this growing need for, or growing imposition of, defined borders. The Palestinian reality is a kind of extreme case study in defining what a nation is or can be.” However, even what turned out to be a minor gesture of change in the institution’s accession policies strengthened advocates for other aggrieved populations, “I’ve had all the possible questions: ‘What about the Kashmiri pavilion?’ ‘Why don’t you do Kurdistan?’ It’s never-ending.”

Responsibility involves courage and imagination. Alessandro Petti and Sandi Hilal today are DAAR – Decolonizing Architecture Art Research and received the Golden Lion for Best Participation in 2003 from the International Architecture Exhibition for “their long-standing commitment to deep political engagement with decolonization architectural and learning practices in Palestine and Europe.”

The Ties Between the Cultural Institution and Politics

When did it happen that politics began to manage the exhibition decisions? As a public cultural institution, shouldn’t that be a public good to pursue? Just to give a brief overview, the International Art Exhibition was conceived and established by the city of Venice in 1894, which ran it until 1930. The institution had final recognition only with Law No. 3229 of Dec. 24, 1928, which changed its name to “International Biennial Exhibition of Venice”; two years later, Royal Decree Law No. 33 of January 13, 1930, converted into law on April 17, signed by Head of Government, Prime Minister Secretary of State, Minister of the Interior Benito Mussolini, [12] constituted it into an autonomous body: “(…) the autonomous body holds its own right, implements its own will which is distinct from that of the state, has autarkic power and administers in its own name, and freely performs the function for which it is permitted.” [13]

The period from the foundation to 1930 can be defined as that of municipal management. Until then, the institution had been chaired by the mayor, directed by a secretary general, supported by a board of directors (consisting only of artists, art historians and art critics), and financially dependent on the City of Venice, which approved its budgets annually. Between 1928 and 1932 the institution was nationalized and placed under the direct dependence of the central organs of the executive. The policy of reforms that the Mussolini government was applying to all Italian cultural institutions to centralize them in the hands of the state, in order to control them and use them for propaganda, [14] finally took over the Biennale on July 21, 1938, when the Decree Law No. 1517 established the “New organization of the Venice International Biennial Art Exhibition.” [15]

From this moment, the second period of the institution’s life begins, that can be defined as its “bureaucratization”, which continues to this day. By keeping “Venice” in the new name even though the institution was no longer run by the city that had founded and administered it for more than 30 years, the Ministry of Popular Culture declared its interest in strengthening the link between Venice, a prestigious showcase for Italy, and the institution that had meanwhile become a stage for international art. For the Mussolini government, the International Art Exhibition became the ideal strategic place for regime propaganda to play in international diplomacy, by placing it at the top of the pyramid of the Italian exhibition system.

Promulgated in 1938, the first article of the statute permanently changed the name of the institution by removing the dust from the previous Belle Époque denomination and decline it in a futurist key by placing emphasis on its characteristic temporality: “La Biennale di Venezia Esposizione internazionale d’arte.” That’s when it famously became “the Venice Biennale” for everyone. But how many are aware that the very name of the institution is a fascist legacy? This coincided with the moment the Biennale became a public institution, and this is why I refer to it as the “International Art Exhibition”—although I still wait for a new denomination to be found, more appropriate to the times.

Between 1938 and the 1973 reform, the only decree promulgated was the 1947 decree that provided for the removal of fascist terminology from the statute: Duce, Venice Podestà, and the Ministry of Corporations became president of the council, mayor of Venice, presidency of the Council of Ministers.

Then the 1968 protests shone an international spotlight on the paradox according to which a public cultural institution of a country that had been democratic for more than twenty years was still relying on a fascist statute. After an endless parliamentary process, the Italian government arrived at the proclamation of the reform law July 26, 1973 No. 438, “New regulations of the autonomous Body ‘La Biennale di Venezia’”, which completely transformed the institution for the second time since its establishment, while maintaining its institutional soul. [16] The final piece of legislation would not be recognized by Senator and Chairman of the Public Education and Fine Arts Committee Giovanni Spadolini, as that “conformed to the inspiration that flowed from the fact-finding survey,” as the chamber of deputies made changes and revisions “radical in their results.” [17] The first article established that the institution “shall from now on be named ‘Ente autonomo La Biennale di Venezia’ (…) a democratically organized cultural institute, and its goal is the promotion of permanent activities and the organization of international events relating to documentation, information, criticism, research, and experimentation in the field of the arts.” [18] Although the new law brought the International Art Exhibition in line with the principles of Italian democracy by guaranteeing plurality through the democratization of its new structural arrangement, on the day the statute was proclaimed, Spadolini pointed out how the hasty conclusion of the law, due to the urgency of bringing the exhibition back to life after the 1968 tsunami, had been the cause of many procedural inconsistencies and the inapplicability of many articles. [19] As art historian and politician Giulio Carlo Argan wrote, “after a troubled gestation, the new statute was born deformed, a child of too many fathers. It reforms the characters of management and the division of powers; it mistakes representations for competences; it ignores the basic problems of cultural structure and function.” [20] The agitated passage from the Senate to the Chamber had resulted in the proclamation of a compromise statute that absorbed the most progressive instances of contestation, but in a quite confused way. In addition, it was immediately visible how the composition by collegiate bodies, supposed to guarantee autonomy and democracy for the institution, created a plethoric structure that rendered management difficult. Spadolini continued, “particularly in such a delicate and essential field of relations between culture and political power (…) there are no dogmatic and definitive truths,” and called for a healthy distance of the state from the things of culture and art in order to avoid forms of “reciprocal enslavement or instrumentalization,” asserting that “culture does not belong to any pressure group or power,” but is “the result of a complex of social forces that must find a possibility of confrontation in public manifestations…” [21]

Despite the reform law, the International Art Exhibition remained a public body, as defined by the 1930 statute, therefore its seats were politically assigned “according to the most scrupulous democratic rules,” [22] and even the appointment of board members was the result of a “wild allotment” that relied on the bargaining among political parties.

Then the legislative Decree No. 19 of January 29, 1998, transformed the “autonomous Body ‘La Biennale di Venezia’” into a Cultural Society, i.e. a “private legal entity” owned by the Ministry of Cultural Heritage, the Veneto Region, the Province of Venice, and Venice Municipality, and a small percentage of private entities. The president is appointed through a decree of the Italian Cultural Heritage Minister, “after hearing the standing competent committees of the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate of the Republic,” as well as the board of directors. Finally, the Legislative Decree No. 1 of January 8, 2004, made some changes and additions to the ’98 Legislative Decree, transforming the Society of Culture into “Fondazione La Biennale di Venezia (…) acknowledged as preeminent national interest, which has a legal status under private law, and is governed, unless expressly provided for in this decree, by the Civil Code.” The “Fondazione La Biennale di Venezia” depends on the Italian ministry in appointments, management and funding.

The past to Imagine the future

Even if the International Art Exhibition was defined as a “democratically organized institution” that was to ensure “full freedom of ideas and forms of expression,” the 1973 reform had not achieved the desired ideal. But article 9 stipulated that the Governing Council should deliberate on a “four-year outline plan for the activities of the institution.” The positioning of the “new Biennale” is fully and clearly expressed in the “Foreword”, as a matter of fact, it qualifies itself in the will to “operate nationally and internationally with a clear and unambiguous antifascist choice, both vis-à-vis the role of privilege and the cultural hegemonic structure as an élite fact, in regards to Countries subject to fascist and oppressive regimes,” in particular it gives itself as an objective to “establish direct relations (…) with artistic forces operating in exile.” [23] This gives a context to that historical period, which still confirms that it is the will of individuals that determines the positioning of an institution.

As we have seen, the new law was rough, and I would like to dwell in particular on the issue of article 10, which stipulated that the “participation in the organization’s events” was “conditioned on the direct and personal invitation extended to the authors by the board of directors.” [24] With article 10, not only countries lost their traditional autarky from the International Art Exhibition, but were essentially deprived of it. One of the slogans of the ’68 protest was “Biennale of bosses, we will burn your pavilions!” because they were considered emblematic of the exclusivity of what was supposed to be a democratic institution that was instead blatantly more interested in diplomatic and economic relations disguised as artistic event. In 1969, for fear of losing their pavilions, commissioners inquired with the presidency for their representation on the board of the International Art Exhibition to be included as well. [25] As a matter of fact, representatives of foreign countries were an integral part of the structure of the International Art Exhibition, which they made possible by fully financing their own exhibits. [26]

This becomes a legal issue that president Carlo Ripa di Meana and Visual arts director Vittorio Gregotti decide to address through an assembly, by convening a tight series of meetings with representatives of the nations owning the pavilions, in the presence of an administrative law consultant to resolve the mutated relationship as imposed by the law, trying to stick to its scope. In the official declaration that followed the meetings with the legal consultants, the president was able to communicate to the countries his intention to remain faithful to the statute, but at the same time to seek coordination for a better use of the “patrimony of the Giardini di Castello by Italy and other countries, in the spirit of the ‘new Biennale’.” [27] The president proposed that with the agreement of foreign countries, the International Art Exhibition would constitute a “moral state property.” [28] The “state property” is that “complex of assets belonging to the State and other territorial public bodies, as they are intended for the direct or indirect use of citizens,” therefore the “moral state property” would have established an agreed use of the common spaces and cultural programs, according to unanimous approval among all the actors who contributed to the realization of the edition’s events, in the public interest.

The idea was that due to its nature and history, the International Art Exhibition would be the ideal platform for the creation of “an authentically international expression,” going so far as to present artists who also worked in different countries other than those that would have represented them at the Giardini, thus giving a broader vision to the cultural work of the Exhibition. As Vittorio Gregotti declared, “contemporary culture fundamentally has this characteristic: of being an international culture,” [29] convinced that the fundamental purpose of the assembly with the participants was not to defend representations and spaces, but to try to collectively re-establish an objective for the International Art Exhibition by overcoming its national character. Gregotti was convinced that the issue of the law and the selection of artists could be overcome through a shared endeavor by identifying “some fundamental themes for all countries, and trying to find an agreement around them, and therefore a criterion for the choice, and a possibility of comparison between the different choices around one common issue.” [30] This is how the thematic International Art Exhibition was born, on the real and concrete commitment towards inclusiveness, in order to overcome the exclusive national character.

Another useful document as a basis for imagining a possible future is the “Giardini della Biennale” Detailed Plan, drawn up by the Municipality of Venice in 2001 which formalizes the concession of the area to the International Art Exhibition. [31] In this document there’s a chapter titled “Area Giardini di Castello – Condominio dei Giardini” that reads: “The Municipality of Venice hereby acknowledges that on the initiative of the Biennale, it must [be received] within six months of the signing of this agreement [to] the definition of a specific agreement with the foreign states that use the Pavilions for the establishment of a condominium between the Venice Biennale, the Municipality of Venice and the foreign states themselves to regulate both the common use of the areas and buildings, and the maintenance, guardianship and organization of services relating to areas of common use.” [32] The “condominium” is a “property right common to several people, co-ownership. […]. By analogy, c. internazionale (international condominio) is an exceptional situation in which a territory is subjected to the sovereignty of two or more states, each of which must admit that the other, or the others, contribute in the exercise of sovereignty itself.”

It is interesting to note that in 2006 it was still the municipality of Venice that had to point out to the Exhibition, that the competence of the concession area should be shared with the other subjects present in the territory, namely the Municipality and the foreign pavilions. This agreement had to be formalized within six months and had as its founding principle the “opening of the area to the public during the year with the exception of the periods in which events are held.” [33] It is clarified that the Municipality was awaiting the establishment of the condominium to evaluate the methods and conditions for public use of the garden area. Furthermore, the “modalities of possible and different fencing or security systems” had to be agreed between the Biennale and the Municipality which would bear the related construction costs. There have never been any replies other than the obvious de facto privatization of the territory by the institution.

Today we would define both the “moral state property” proposed in 1974, and the “condominium” hoped for by the Municipality of Venice in 2006, as attempts to transform the International Art Exhibition into a “common”, or a “constitutive institution” that could generate social change. Adherence to these proposals would have placed the institution at the forefront of the current discourse of alter-institutionality which radically re-examines the role of institutions in society, rethinking new structures. [34] Only by reassessing these concepts and by overcoming its borders, the International Art Exhibition could possibly today project social, political and artistic functions with renewed relevance, as an institution that is unique for its history and for its multidisciplinary and international nature.

The context is the content

If the territory that the International Art Exhibition occupies is mainly the one enclosed within the borders of the Giardini, today it is a real colonization of a whole city, Venice, which is undergoing a form of violent and brazen extractivism. Venice and its exhibition were born in 1894 in a healthy and productive osmosis that lasted until the arrival of the presidency in 1930 (and remained until 1943), of the Plenipotentiary Minister, governor of Italian Tripolitania (1921–25), Minister of Finance (1925–1928), first prosecutor of San Marco (1927–1947), president of Confindustria (1934–1943), the entrepreneur Giuseppe Volpi, who later became noble, thanks to the fascist title of Count of Misurata. Volpi had a hyper capitalistic vision that today we would define as neoliberal, based on the centralization of wealth; he was the one who founded the Marghera petrochemical plant which poisoned the lagoon for decades, and destroyed the fragile ecosystem; he founded the Venice International Film Festival in 1932 in one of his hotels on the Lido, as president of C.I.G.A.—the Italian Grandi Alberghi Company, one of the largest global groups operating in the high-level hotel and luxury tourism sector, again founded by Volpi in Venice in 1906. From that moment on the International Art Exhibition has been used to parasitize Venice , along with other sector events born in the meantime. This drift goes hand in hand with the nationalization sanctioned by the law of 1930 and the branding of the denomination in “Biennale” keeping the mention “Venezia” for marketing purposes only.

The awareness of a public cultural institution lies in acknowledging these facts, not to consider them charges, but rather part of its history, that is necessary and urgent to deal with. Just as it is not possible to separate the International Art Exhibition from the city of Venice, it is not possible to separate the container from the content, because the message that is launched from inside the national pavilions is the direct expression of the institutions of power belonging to a system this is an expression of and its echochamber—so any message that seeps through them will inevitably be ambiguous and ambivalent. [35] What is exhibited in the national pavilions ceases to be relevant because it is sufficient for the institutional machine, as a medium, to legitimize its entry and confirm its presence in the system, effectively neutralizing and engulfing any, albeit critical, will of the artist. The walls of the pavilions themselves are borders with flagpoles on which the national flags are hoisted.

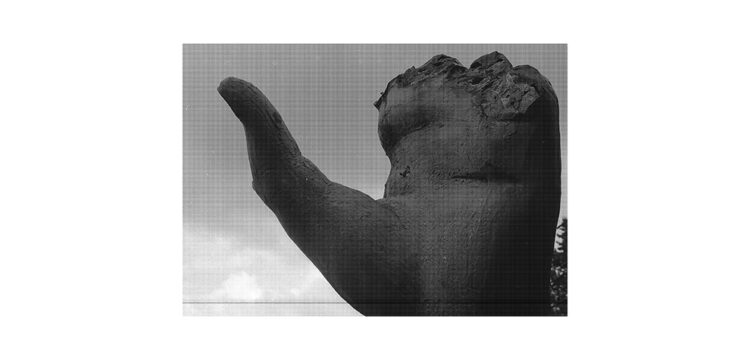

The “Giardini della Biennale” are a micro-city, a geopolitical theme park (I really appreciate the “diorama” definition), in which History is revealed in the details of its urban planning, in the architecture and in the management of the pavilions, each characterized by its own historical specificity. [36] In this place more than anywhere else, architecture is a symbolic representation of the economic, political and cultural power of a Nation. As a place separated from the urban fabric, and moreover as an exhibition space, the International Art Exhibition becomes a fictitious territory that produces a reality that symbolizes the social and economic representation of Art, as the national pavilions thus become perfect machines for the legitimation of national identities. Ukraine’s honorary promotion with an official pavilion in the Arsenale is clearly not only a noble gesture of solidarity, but seems to become an agreed first step to legitimize its request to join NATO. At the same time, the entry of countries recognized by the Italian government, that have recently obtained official spaces despite not guaranteeing the standards of the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights, tells us a lot about Italian economical interests.

The responsibility of an institution must first and foremost be political, just like any positioning is a political act. I make the words of the artist Alessandra Ferrini my own, “Italy has been refusing to deal with its postcolonial present as a result of the systematic refusal to acknowledge its colonial past (…) we need to first understand the history that has created this condition (…) it is fundamental to develop a sense of collective responsibility (…) Fascism ruled for two decades. Yet the seeds of its ideology can be found in earlier systems of thoughts, the so-called proto-fascism. The imaginaries to which they alluded were deeply entrenched in colonial politics and propaganda. And more largely, in the construction of national identity that began with the Italian unification in 1861. If you add to the equation that there was no reparative justice or process of defascistization after WW2 (contrary to Germany where Nuremberg trials played a central role in undergoing denazification) these deeply rooted ideologies have been able to survive quite unchallenged. Then there are more latent manifestations of racism and nationalism (rooted in fascism) that pervade most discourse, including, at times, of the Left.”

A collective removal, even for the simple fact that we still unconsciously call it “the Biennale”, or better to say “The Biennale.” The International Art Exhibition must deal with its own past, and inhabit its own history, this process of defascistization must begin from changing its denomination, and by keeping on reviewing the architecture of the central pavilion facade, a 1932 design of little value, but still bound by the Superintendence like anything else inside the Giardini, trees included. If trees can be uprooted, so can other features. Why not hold a competition for a new facade for a building that is also home to an International Architecture Exhibition? [37] The 1932 facade was boycotted in 1968 by Carlo Scarpa, who was aware of its meaning; later on the lion of St. Mark and the eagle with the fasces and the writing in the regime’s font which today rests on the back of the Italian pavilion mysteriously disappeared and now it has become, perhaps in a more grotesque manner, a monument. [38] That facade was played down by the various directors of the international exhibition, who invited artists to intervene, although none of them ever actually worked on the memory of what that symbol of the institution actually represents. [39] All these camouflages are of no use unless the institution itself is able to introject and inhabit a legacy, so as to avoid arriving at the current hard-line “politics vs art”—which only clarifies how come that naming and that facade are still there untouched.

It is time to make an effort in learning the history, and how the system of this institution works, and it is time for this discussion to become public knowledge, because The Biennale is a public cultural institution, and because today more than ever, we art workers need to be on the alert, and informed, and aware of how our cultural institutions are instruments of production of political propaganda rather than culture. Otherwise we stand complicit.

If “La Biennale di Venezia” were a private institution, managed with private money, this discussion would make no sense, but since it is in fact a public body, we are talking about an institution that should be a common like all other public institutions, especially those that produce and promote culture.

The International Art Exhibition confronts us with all the dysfunctions of globalization, that at a certain point made us believe that the idea of the nation-state could become obsolete, because on the contrary, neoliberal society needs stronger nation-states to centralize as much wealth as possible within few hands, and strict borders; the current hypertrophy of requests for national pavilions today is as strong as when it was established, i.e. in the era in which contemporary borders were being defined. Today more than ever, nationalism is the brand of this dark historical moment in which walls are built, cultural identities are ignored or trampled upon, and goods can travel without limitations, but not people.

I would like to end with a note by Vittorio Gregotti from 1974—“to clarify that the new Biennale addresses the problem of culture and art directly as such, and not as state policy.” [40] I signed ANGA’s open letter, convinced that it was necessary to open a debate, and as they declared in response to the authoritative words of the Italian Minister of Culture, the Exhibition is not a “disinterested party on the global stage of culture.” However, with this text I would like to convey the message resulting precisely from the very fact that this institution is defined as a “party” precisely because it is a real political actor. The call for a boycott towards a Nation, represented by the Israeli pavilion, does not take away the fact that the presence of all the art workers in the other pavilions and in the international exhibition is on another hand not complicity. Ethical coherence is an essential asset for being consistent art workers. It takes courage and imagination to take the institution out of the hands of state politics and put it back in the hands of art workers, as it originally was, towards a direction that allows us to imagine that world confederation of free states that Bertrand Russell hoped for as the only solution for peace. A power unknown to politics, the power of the work of the art workers relies precisely in the capacity to imagine alternatives, in the possibility to dissent and disrupt in order to convince the very same politics to listen to art and cultural workers, to those who have the tools and the right to productively manage that international common for whom and by whom it was founded.

[1] It is interesting that this is not said on the English page. The ASAC, the object of large-scale funding during the Baratta’s years, is frequented today by international scholars, despite remaining opaque and elitist.

[2] I apologize here publicly to Cecilia Alemani who, in times of Covid, had to take on such demanding work that exceeded her already difficult and demanding tasks, because an exhibition like The Disquieted Muses would have required at least two years of preparation with a team of specialists, rather than a palliative exhibition to fill the absence of an edition.

[3] The Istituto Luce is an Italian holding founded in 1924 by Benito Mussolini to make it the most powerful instrument of fascist propaganda. It is the oldest public institution dedicated to the diffusion of cinema for educational and information purposes in the world.ì

[4] “Since the early 1950s, Bertand Russell called for an institutional reform of the UN, since the Security Council could not become the germ of a world government due to the veto power of its member states; as on the occasion of his criticism of the League of Nations, the British philosopher supported the ideas of those who, over the centuries, had interpreted international relations starting from the analogy according to which States could be considered as citizens belonging to the same community; hence the need to transfer the traditional natural law model from the individual to the interstate level, since the individual countries were still in a sort of potentially belligerent state of nature. Through his idea of world government, he applied Hobbesian contractualism in the Kantian sense, attributing to it a cosmopolitan value”, in Anta, C. G., Bertand Russell: the idea of a world government, in “Il Politico”, 257(2), 23–42, 2023.

[5] I define it as a “territory” as it is an area of the Napoleonic public gardens that was removed from public use when the exhibition was established in 1894; to leave space for the exhibition venue, borders were defined (with gates and walls) that circumscribe the perimeter within which the institution exercises its sovereignty. Cfr. Martini V., “The Giardini: Status of the Property”, in AA.VV., Maria Eichhorn. Relocating a Structure, German Pavilion 2022, 59th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, pp. 293-297.

[6] Big part of the research concerning laws and archival documentation comes from my Phd dissertation, Martini V., La Biennale di Venezia 1968-1978. La rivoluzione incompiuta, Dottorato di ricerca in Storia dell’architettura e della città, scienze delle arti, restauro, 22° ciclo, SSAV–Fondazione Scuola di Studi Avanzati in Venezia, Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia/Università Iuav di Venezia, 2011.

[7] The relationship between the foreign country and the International Art Exhibition was taken for granted as being one of complete autonomy already in 1938, so much so that no mention of it appears in any article or footnote in the reform law.

[8] The “excessive width” of the Italian section undermined any innovative intent of the art exhibition and became a national issue, as Pallucchini again exasperatedly noted in the 1956 catalogue: “evidently there were not enough exhibition structures in Italy and the Biennale had become the only exhibition venue and the only opportunity for Italian artists”, R. Pallucchini, Introduzione, Catalogo XXVIII Esposizione Biennale internazionale d’arte, Alfieri 1956, p. XVII. In 1968, Pino Pascali described the Biennale as follows: “a rotation whereby all Italian painters sooner or later have the opportunity to exhibit. It’s not a shrine or anything. It’s a dirty place where one has the opportunity to exhibit one’s paintings even to people at a higher cultural level than ours.” P. Pascali, Io la contestazione la vedo così, in “Bit arte: oggi in Italia”, n. 3, 1968, p. 49.

[9] Società di cultura La Biennale di Venezia, Statuto adottato dal Consiglio di amministrazione nella seduta del 27 luglio 1998. The Board of Directors is made up of the President, the Mayor of Venice, a member of the Venetian Regional Council, a member of the Provincial Council of Venice, and a designated private entity.

[10] The Giardini have hosted the Russian Pavilion on its territory since 1914. From the outbreak of the First World War to 1920, the Russian pavilion remained closed. When the Russians returned to Venice the first thing they did was to eliminate the eagle on the top of the roof of the pavilion, the symbol of the tsarist empire which had fallen in the meantime. At the same time, the writing “USSR”appeared on the facade: Russia had become the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. The pavilion closed in 1922 to reopen for the 1924 exhibition, the year of Lenin’s death. In 1928 the “Stalin era” began, and from that year the USSR participated in the Biennial with a commissioner who curated nationalist propaganda exhibitions. The pavilion closed definitively in 1934. In 1948, after the Second World War, the International Art Exhibition reopened and among the first things tried to invite the Russians to return to their pavilion. The USSR responded to the invitation by asking which other nations were present: having received the response from the Venetian institution, the USSR no longer responded and did not participate in that edition. When Stalin died in 1953, his reputation as a champion and emancipator of the oppressed masses was still intact. We had to wait until 1956 when Nikita Khrushchev, Stalin’s successor, denouncing his crimes and deviations, started the process of “de-Stalinization” and the consequent theory of “peaceful coexistence”, which would lead to the thaw of diplomatic relations with Russia. In 1956, Russia decided to reappear on the international scene by choosing their pavilion in Venice as the stage. But the return was preceded by a curious request: the Russian delegation asked the International Art Exhibition for the availability of a permanent presence in the pavilion who would be available to visitors to explain the works on display for the entire duration of the exhibition. The director of the institution responded in dismay that the treatment of the various nations present had to be absolutely fair… disturbing to know that the same request had also been forwarded shortly before by the United States. It was the beginning of the Cold War. Since 1991 the Soviet Union formally ceased to exist and the following year Russia was recognized as having the international status held by the Soviet Union. In ’95 the writing “USSR” on the facade was replaced by “RUSSIA”.This short political/economical history of the Russian pavilion (as for the US one later on), is the archival research I did for Antoni Muntadas’ installation On Translation: I Giardini, Spanish Pavillon, 51st Venice Biennale 2005 (unpublished).

[11] The United States had participated in the Biennial since the first edition, but since the American government does not directly intervene in any artistic event, it was a private individual, the president of the Grand Central Art Galleries, who financed the construction of a pavilion. The Grand Central Art Galleries was a New York cooperative of artists, amateurs and art collectors. The Americans chose the prestigious area where the café-restaurant had stood since 1907 and which the International Art Exhibition gave permission to demolish. The project was entrusted to Aldrich&Delano, famous in their homeland for the villas designed for American high society. For the American pavilion in Venice, the two architects took inspiration from Monticello, the famous home built by Thomas Jefferson in Virginia. Monticello had become the model of official American architecture: halfway between an eighteenth-century colonial villa and a neo-Palladian villa in the English countryside, it reflected the sum of the American ideals of democracy and equality. The pavilion was inaugurated in 1930. In 1942, the United States pavilion was occupied by the Royal Italian Navy. In ’48 the United States returned to Venice with Peggy Guggenheim who brought the first “American” works of art after a long time. But Peggy Guggenheim’s collection did not officially represent the United States and, in fact, it was exhibited in the Greek pavilion which remained empty due to the civil war raging in that country. The United States pavilion, after many years of closure, was in a state of abandonment and the official exhibition did not open until July of that year. To justify the delay, the US government blamed the Italian elections that were held in Italy in April. In 1950 the American government refused to take over the pavilion that Grand Central Art Galleries wanted to sell for a symbolic price. US critics accused the government of a total lack of interest in participating in such an important international art exhibition. That same year, at the Biennale, private individuals once again organized the exhibition which met with great success. A few years earlier, in 1947, the CIA was born, the international intelligence system that became indispensable for the United States after the Second World War. Following the success of the American exhibition in Venice, the CIA realized the potential of an exhibition like the Biennale: it was an ideal “neutral territory” for propaganda.

In 1954, ownership of the pavilion passed to the Museum of Modern Art in New York. MoMA and the CIA would constantly collaborate on tight propaganda during the Cold War. MoMA will purchase the pavilion using money from ICE (International Program of Circulating Exhibitions), one of the many fictitious organizations created by the CIA. MoMA maintained ownership of the pavilion until 1987. That year the ground grant expired and, instead of renewing it, the museum made a private agreement to sell the pavilion. Since 5 February 1987, the ownership of the American pavilion has belonged to the Guggenheim Foundation which has a branch in Peggy Guggenheim’s former home in Venice. The US pavilion is the only one to be managed by a private institution.

[12] The decree was also signed by the Minister of Corporations Giuseppe Bottai, the Minister of Finance Antonio Mosconi and the Minister of National Education Giuliano Balbino.

[13] Ragghianti C. L., Per uno statuto costituzionale dell’ente autonomo “Biennale di Venezia”, in “Rassegna Parlamentare”, Giuffré, n. 10, ottobre 1960, p. 1682.

[14] This series of reforms affected all Italian artistic structures, up to the administration of Fine Arts which, with the law of 1 June 1939, gave an almost exclusive monopoly on works of art to the National Gallery of Modern Art in Rome, the only one with a national configuration.

[15] Regio decreto-legge 21 luglio 1938-XVI, n. 1517.

[16] The law was voted by the center-left majority and the liberals, while the Communist Party and the left-wing independents abstained; right wing party MSI voted against.

[17] G. Spadolini, Epilogo per la Biennale Epilogo per la Biennale. Discorso sulla legge per lo statuto della Biennale pronunciato in Senato il 25 luglio 1973, Bardi 1973, p. 4.

[18] Biennale di Venezia. Annuario 1975 Eventi 1974, edited by Archivio storico delle arti contemporanee, La Biennale di Venezia 1975, p. 31.

[19] The only way out was offered by the old fascist statute which was still valid.

[20] Argan G. C., La Biennale e i suoi killer, “L’Espresso”, 24 marzo 1974.

[21] Spadolini G., Epilogo per la Biennale cit., idem.

[22] S. Kessler, Biennale Venedig. Die ‘Flut der Veranstatungen’ und die Probe aufs Exempel, “Frankfurter Allgemeine”, 23 novembre 1974, in Biennale di Venezia. Annuario 1975 cit., p. 552.

[23] “Piano quadriennale di massima delle attività e delle manifestazioni (1974-1977)”, in Biennale di Venezia, Annuario 1975 cit., p. 62.

[24] Art. n.10 of the Law 26 luglio 1973, n.438, Nuovo ordinamento dell’Ente Autonomo ‘La Biennale di Venezia’. Art. n.10 will be modified the 13 june 1977 with law 13 june 1977, n.324.

[25] Riunione dei commissari stranieri per l’organizzazione della Biennale 1970, unità 225, Conferenza padiglioni stranieri, Fondo storico, Serie arti visive, ASAC.

[26] Proposta Norvegia, unità 294, Regolamento Laboratorio, Fondo storico, Serie arti visive, ASAC.

[27] Riunione 2 dei rappresentanti dei padiglioni ai Giardini del 30 ottobre 1974, unità 292, Riunione commissari, Fondo storico, Serie arti visive, ASAC.

[28] Riunione 1 dei rappresentanti dei padiglioni stranieri ai Giardini del 31 luglio 1974, unità 290, 31 luglio 1974, Fondo storico, Serie arti visive, ASAC, “The expression ‘moral state property’ is ideological and not technical; it must not be understood literally with respect to the word state property which evokes the idea of expropriation.”

[29] IX Riunione del Consiglio direttivo, 26 luglio 1974, ASAC.

[30] Riunione n. 1 dei Rappresentanti dei padiglioni ai Giardini del 31 luglio 1974, cit.

[31] Here I repeat exactly what I published in Martini V., The Giardini: Status of the Property cit. Comune di Venezia, Assessorato all’Urbanistica, Piano Particolareggiato “Giardini della Biennale”, Fascicolo A – Stato di Fatto, Allegato A2 – Elenco catastale Proprietà, Allegato alla delibera di approvazione del Consiglio Comunale n. 103 del 20/09/01, p. 7.

[32] Comune di Venezia, delibera del Consiglio comunale n. 137 del 25 settembre 2006, titoled Approvazione della convenzione disciplinante l’uso da parte della Fondazione La Biennale di Venezia dei beni di proprietà comunale da destinare alle attività che la Biennale promuove.

[33] Comune di Venezia, delibera del Consiglio comunale n. 137, cit.

[34] I am referring here, for example, to the model proposed by L’Internationale https://www.internationaleonline.org/

[35] Muntadas A., Wigley M., “A Conversation Between Antoni Muntadas and Mark Wigley, New York”, in Antoni Muntadas. On Translation: I Giardini cit., p. 277.

[36] Muntadas A., “Notes, November 2004”, in Muntadas. On Translation: I Giardini, 51st Venice Biennale, Actar 2005, p.141.

[37] There is a history of competitions announced and not carried forward for the renovation of the Central Pavilion. There is also a 1972 exhibition entitled Four Projects for Venice. In two rooms of the Central Pavilion in the Giardini, the exhibition illustrated the projects that Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier, Louis Kahn and Isamu Noguchi had created on public commissions, for four infrastructures for Venice that were never built. Among these, Kahn’s was for a new pavilion for the International Art Exhibition.

[38] Cfr. Bertolino G., Martini V., “Utalia. Retrospectives, perspectives and glosses on the most recent Italian art”, in That’s It!, exhibition catalogue edited by Balbi L., Edizioni MAMbo 2018.

[39] The exhibition The Disquieted Muses cit., had played with the history of the different facades of the Central Pavilion through elegant 1:1 scale blow-ups mounted close together to the actual facade and leaving clearly visible and playing on the three-dimensionality of the 1932 columns, the same ones that Carlo Scarpa found offensive.

[40] Appunto per il presidente, 18 ottobre 1974. Oggetto: incontro esame problema padiglioni stranieri alla Biennale-Giardini, unità 293, Varie, Fondo storico, Serie arti visive, ASAC.