The Material of an Exhibition

“All the stories that have not been translated, that have been erased and forbidden to be told…”

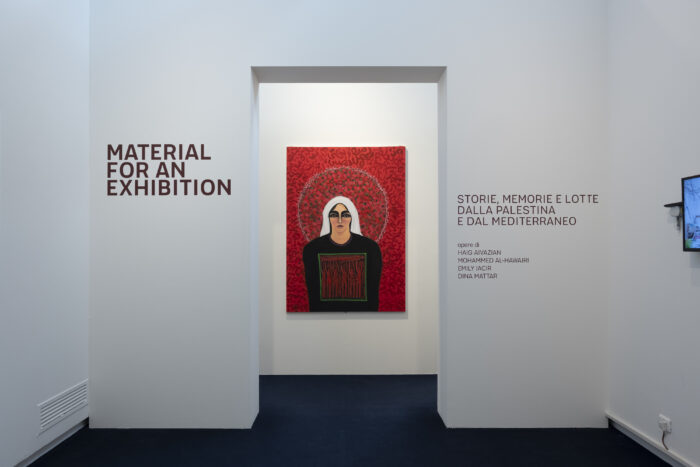

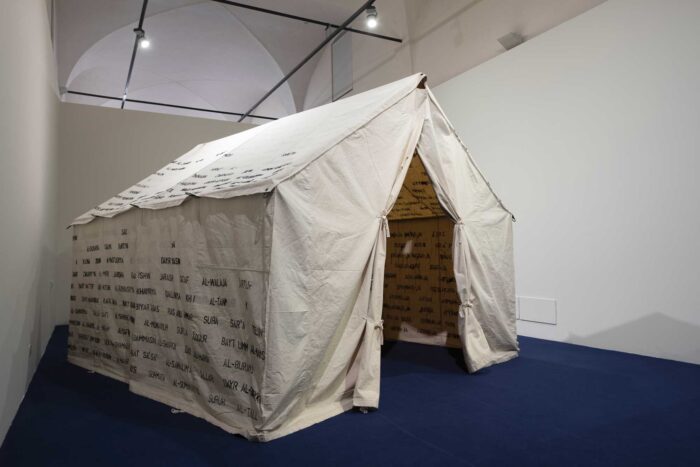

The show MATERIAL FOR AN EXHIBITION. Stories, Memories and Struggles from Palestine and the Mediterranean, on view at Fondazione Brescia Musei, Museo di Santa Giulia, until 22 February 2026, is curated by Sara Alberani and features works that survived the bombing and destruction in 2023 of the Eltiqa Group for Contemporary Art, a space for contemporary art in Gaza. Two of the founders of the Eltiqa Collective (“Encounter” in Arabic), artists Mohammed Al-Hawajri and Dina Mattar, are invited to participate in the ideal reconstruction of this artistic space. They are joined by Lebanese artist Haig Aivazian and Palestinian artist Emily Jacir, winner of the Golden Lion at Venice in 2007.

The exhibition highlights the role of art as a practice capable of building relationships and forging bonds of solidarity between the geographies of the Mediterranean. The works on display give substance to memory—beginning with Emily Jacir’s Material for a Film, as the exhibition title recalls, dedicated to the Palestinian poet and intellectual Wael Zuaiter—making visible the material, political and affective conditions that permeate artistic practice.

This conversation with Mohammed Al-Hawajri, Emily Jacir, Dina Mattar, moderated by Sara Alberani, took place online on September 9, 2025, between Rome and Sharjah. It is crucial to emphasize the temporal and historical context within the reflections presented in this space. What follows is an excerpt from the exhibition catalogue published by Skira (Milan, 2025).

Sara Alberani: An exhibition is an occasion to gather, to reveal, to remember, to expand, and to anticipate what the public will encounter and come to understand as it moves through the museum spaces. In this case, Fondazione Brescia Musei will host your works for several months in Italy. How do you perceive this opportunity within such a crucial historical moment?

Mohammed Al-Hawajri: This exhibition is extremely important for me and for Dina, especially because many of the artworks are physically coming from Gaza, which is also where we come from. The journey of these works has been difficult, and their arrival here, in this particular moment, carries deep significance for the Italian context.

People often have a fixed or stereotypical image of Gaza, a place associated with killing and destruction. In this sense, art arrives as a surprising element: it allows people to understand that there is artistic life in Gaza. This is why the exhibition matters—it shifts the way our works are seen and offers another image of Gaza, beyond that preconceived construction that exists elsewhere. Through art, people can encounter a different Gaza. Therefore, it is essential that we have spaces where communication and exchange can truly happen.

Dina Mattar: People should understand how difficult the story of these paintings is, how hard it was for them to leave Gaza. The journey of these works has been a challenge in itself, and when people see them in our hands, they recognize that the exhibition is truly important.

It is equally meaningful for the public to understand that the subjects we depict speak of a beautiful life. Before the genocide and before the war, our lives were beautiful, and we have painted these memories within our works. Through them, we speak about our lives—about hope, about love, and about the nature that surrounds us, our beautiful landscape of olive trees and orange groves. It is essential that people also see these things, and not think of Gaza solely as a place of death and destruction, a place to flee from, but recognize instead its beauty and the life that continues to exist there.

We also want to emphasize that we persist, despite everything—despite the events, the circumstances, and the fact that our families are still there, still in Gaza. Every morning we wake up to loss; we follow the news, wondering what will happen to them. Yet, despite it all, we remain determined that the whole world must hear our voices and listen to our message.

Emily Jacir: Sara, this exhibition is incredibly important for many reasons. But for me personally, one of the most meaningful aspects is being able to share it with Mohammed and Dina. For a long time, there has been a tendency to create separations—a Gaza show, a Bethlehem show, a West Bank show—whereas we are one people, a whole society that has been forcibly fragmented. What matters here is that this exhibition brings us together. It is profoundly important at this moment. People must not forget that we are one body, one people.

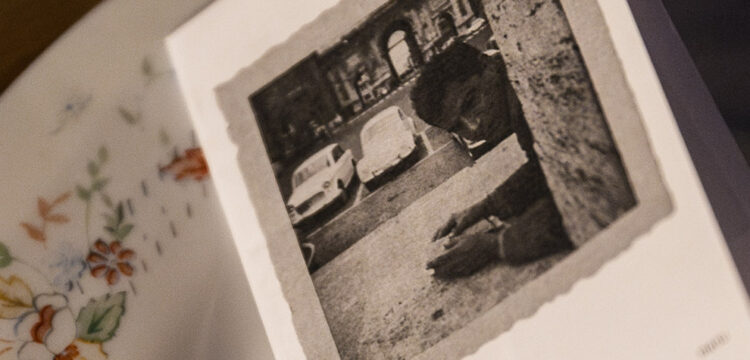

SA: The title of the exhibition Material for an Exhibition pays homage to Emily’s work Material for a Film, which is included in the show. Dedicated to the Palestinian intellectual and poet Wael Zuaiter—assassinated by Mossad in Rome in 1972—this work traces his life and activity between Palestine and Italy.

The word Material evokes the languages of the exhibition—installation, video, photography, painting, drawing, and works on paper—offering the audience an immersive experience that fosters critical awareness. Yet Material also refers to material conditions: those conditions in which artists from conflict zones create, often marked by the loss of works, archives, sites of memory, and stories passed on by those no longer present. How important are these materials in the Palestinian context?

MAH: The importance of the archive, or of art in all its forms—theater, cinema, painting—lies in its essential role in preserving history and narrative. Throughout the history of art, people have learned, documented, and transmitted knowledge as a way of safeguarding memory. These practices, together with the stories and the well-known Palestinian poets, generate a wide range of materials that help keep the Palestinian cause alive. The struggle has been preserved and passed down across generations, through the works of artists and the transgenerational exchange that carries history, knowledge, and memory forward.

DM: I want to emphasize what Mohammed said: archiving in Palestinian art is extremely important. We can see this clearly today in the media; they often try to silence certain voices, like those of journalists, whose work is also a form of archiving. Artistic works, cinema, and videos all serve as ways of documenting and preserving the Palestinian cause.

Our works, and those of other artists, form a continuous sequence—from the very beginning of the cause until today—an ongoing process of archiving, whether through works that convey positive or negative images.

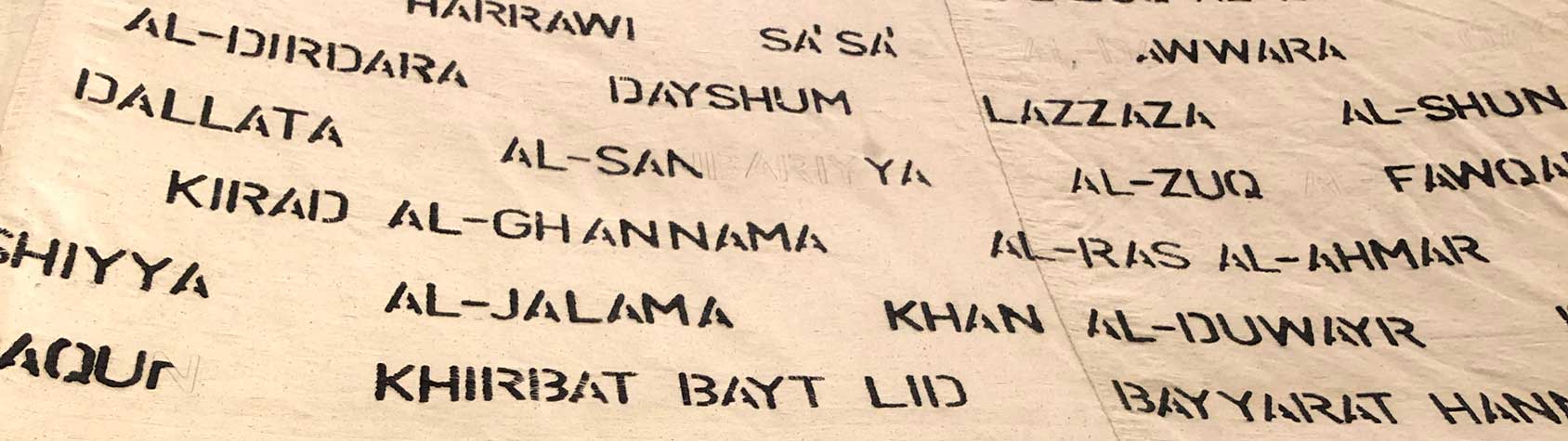

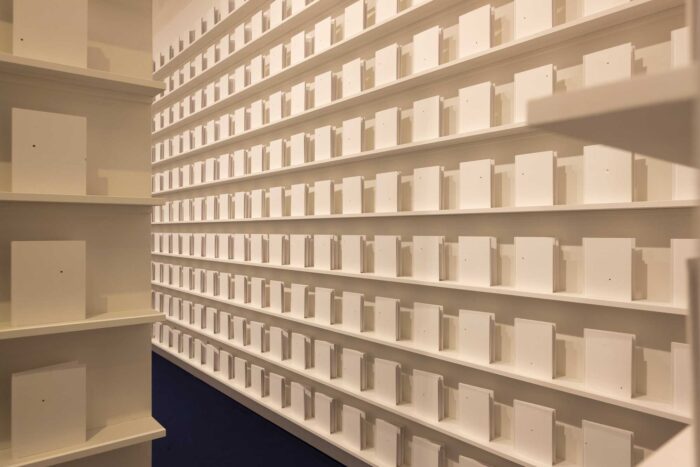

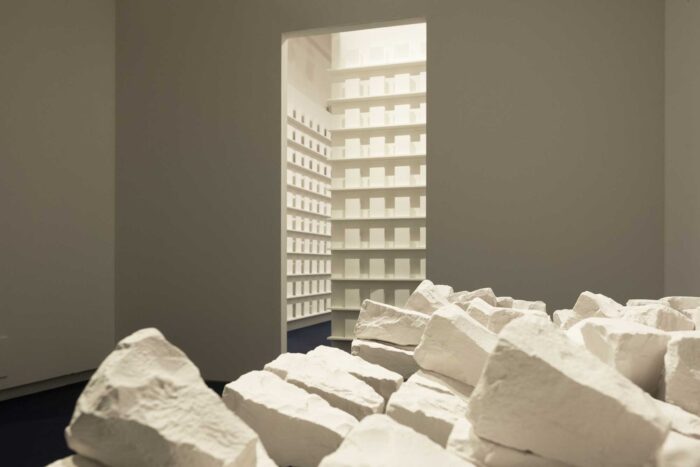

EJ: Wael Zuaiter was a pioneer, and I think that word is essential to understanding who he was. He was a pioneer who went to Italy to speak in Italian and to tell our story in that language. What made him so threatening was that his friends were people like Moravia, Genet, Sartre, Pasolini, Petri—and he was bringing them into our story, showing them what was happening to us. In many ways, I see my work as a continuation of his, a collaboration across time. When he was assassinated, he had a copy of A Thousand and One Nights in his pocket, and one of the bullets hit that book. The symbolism of that truly resonates, especially in this moment, as we exhibit the one thousand blank books each one pierced by a bullet—all the stories that have not been translated, that have been erased and forbidden to be told. The question of materiality is also deeply relevant in relation to Italy. The philosophies, crafts, and religions of the southern Mediterranean, traveled up into its northern shores, in a continuous exchange that lasted for centuries. And if you look at all these fragments of Palestine that exist as relics throughout Italy, it makes me think of that connection: my Via Crucis project in Milan, for instance, is in dialogue with these stones and pieces of wood brought from the Terra Santa. Inspired by this history, and specifically by the practice of collecting and displaying relics from Palestine in Italian churches—as in the unique case of Basilica of the Holy Cross in Jerusalem in Rome—I created a contemporary Mediterranean Via Crucis that recounts both the exodus and the current refugee crisis through the narrative of the stations of the traditional Via Crucis.

SA: What does it mean to you to be an artist, and how do you understand your role as a cultural worker today?

EJ: I don’t think I can answer this question at this moment. Art, in whatever form, feels insufficient right now. Any attempt falls far below the level of grief and destruction that people in Gaza are living through. It’s not enough to speak about the scale of devastation and killing taking place there. It’s just not enough.

MAH: Yes, this question is very difficult, especially at this moment, because the genocide feels far greater than art or the act of being an artist. As an artist, I feel that I now carry a very heavy responsibility; sometimes it even keeps me awake at night, constantly thinking about what my role should be.

EJ: I agree with Mohammed. I don’t sleep, I can’t sleep at night, because I no longer recognize myself either. I am constantly questioning my role at this time.

MAH: Yes, and I feel that sometimes this task becomes even harder when engaging with a Western audience—one that, through Israeli media, has absorbed a distorted image of Gaza as a place of terrorists, criminals, people who do not deserve to live, or “human animals.” Art must now present itself, because art is the closest medium to the Western public, who have been accustomed to art since childhood. It is also about conveying an image that counters the negative one circulating about life in Gaza, so that we can hold on to hope.

I feel that this is where the artist’s role becomes crucial: to create something that engages with the mindset of the West and its audiences. The artist must be aware of how to present an image that can be understood and received from a Western perspective, in order also to break it. I want to mention something important Emily said: now there are people who use certain artists to reinforce the negative image of Gaza, and unfortunately, the war—or the genocide—is also being exploited in this way.

DM: In a war zone, the focus should be on stopping the violence. Yet we continue our work through art because, in the end, art itself becomes an archive.

The role of the artist remains crucial: to reveal not the “right” image, but the real image—the reality of life in our country. We convey our culture through painting and for filmmakers through cinema. The idea is that, as artists, we communicate our experiences in every possible way in order to deliver our message.

MAH: We will probably encounter a certain level of surprise among the audience. How can there be Palestinian artists whose works do not speak directly about the genocide, but instead about culture, life, love, and other themes? Our exhibition will mark an important moment in addressing this perspective.

EJ: I’m also struggling to answer this question. When the genocide began, I felt it was my responsibility to help artists find safety, to reach places where they, their loved ones, and their belongings could be safe. One thing I will never forget is that no one helped us. We were left entirely alone to take care of our own people; we had to pay thousands of dollars to get individuals, one by one, away from the genocide, and that is unforgiveable.

Additionally, every attempt for us to move or gather was blocked, with one clear purpose: to prevent us from being together. I know someone who recently managed to leave Gaza only to be locked in a hotel room in Jordan, forbidden to speak to anyone. This isolation—the deliberate separation of Palestinians from one another—continues everywhere internationally. Egypt, Jordan, the Emirates, the world itself is complicit in this. This is another reason why this exhibition matters so deeply.

At the same time, I feel responsible for protecting our home, Dar Jacir, [2] built in 1880—to safeguard our neighbors and community, to keep planting, singing, and being together. Yet we live in a painful contradiction: while people in Gaza are being killed, we are here trying to live. But we know the families of Gaza would not want us to stop.

The idea of family, of responsibility and care, changes completely in such times. This is why, when we began this discussion, thinking of how to help Ahmed (Mohammed and Dina’s son) became the most important part of the exhibition; because, in the end, this is what it is truly about.

MAH: Yes, what you say is very important, because we feel the same now. We left Gaza, and we’ve been traveling back and forth to Egypt and to the Emirates. We feel alone sometimes, and everything has become very difficult. We miss our lives and the rhythm we once had. In Gaza, we lived surrounded by family; we were part of something larger. Now, every small detail of life feels heavy, like carrying a mountain. It has become very hard to continue living under these conditions, constantly moving from one place to another. Many people do not accept us; they look at us with suspicion, as if we were something to be feared or rejected. We don’t want our children to go through this. It isn’t easy for them, and they deserve a future; for themselves, and for all of us.

SA: I remember when we met in Sharjah, Mohammed and you said that the regimes keep a close watch on artists because they pose a threat to systems of power. Artists have the capacity to reveal those systems. This is why power monitors artists closely: because they understand that artists work through imagination, through anticipating alternatives, possibilities that do not yet exist. If you can imagine something, you can bring it into being. And that potential, the ability to prefigure liberation, to envision what people desire beyond their governments, represents a profound threat. What you said in Sharjah stayed with me.

I also read something, Emily, in a past interview where you mentioned that in critical moments you turn to poetry. That, too, speaks to the power of art and its ability to hold us, to imagine otherwise, and to endure.

EJ: To survive. This is the word I would also use in relation to this question. Right now, the role of the artist is to survive, and to help our community survive. We are in survival mode, and it’s difficult to think beyond it. Poetry, for me, is a form of survival, as it once was for Wael Zuaiter.

MAH: Yes, Sara, I remember our conversation. On the other hand, I believe that people are not afraid of artists, because many understand what artists express. Artists do not lie; they tell the truth. That is why artists are often consider to be stronger than other individuals, like in Palestine. In Europe, artists are trusted because people have grown up seeing, observing, and learning through art. When artists come from different countries or cultures, people can imagine that they have come to share something—to tell a story, the true story of their own land.

SA: I would like to reflect together on the subtitle of the exhibition, Stories, Memories and Struggles from Palestine and the Mediterranean. What do we mean by the Mediterranean? In Emily’s works, the Mediterranean is a recurring presence—a territory that has been geopolitically divided, yet remains historically and presently connected through the peoples who inhabit it, their cultures, and the forms of solidarity that traverse it. Especially today, precisely across the sea, an international movement of support for Palestine is taking shape. I am also thinking of Mohammed’s and Dina’s works, and how a language rooted in the domestic and the everyday intertwines with a lived sensibility that reflects the familiar and affective dimensions of places.

EJ: Italians have a very long and layered history of shared culture, heritage and exchanges with us. We also share a special understanding through the Italian experience—particularly that of Southern Italy—of contemporary history shaped by their own experiences of migration, displacement, and return. We can also look at the legacy of communist and anti-fascist movements, which runs deep across generations. For two decades I have spent much of my time in southern Italy, and there I have always felt a strong sense of connection—and likewise when people from the south of Italy come to Dar Jacir in Bethlehem, they say the same. Northern Italy might feel like another country and the present governments feel like a flash in time, a moment that means very little compared to the long, rooted history that connects us together. It’s also important to me that this exhibition takes place in Italy, because the relationship between Italy and Palestine is historic. Regarding the geopolitical context and the concept of “Europe,” I would actually challenge the use of that word here and the implication that Italy belongs to it. I don’t feel a deep and rooted connection with Europe—I feel a connection with Italy. Italy’s history with us is different, and the notion of “Europe” as a constructed, segmented space is something I would like to disrupt, even contaminate. In many ways, especially in the south of Italy, people feel closer to us than those in many so-called Arab countries. We share a history around the Mediterranean—a shared architecture, rhythm, movement, and craft. There is a deep cultural continuity that resists the divisions imposed by geography or politics.

MAH: Dina and I might share the same answer, as there is a strong connection between us on this subject. In our artistic practice, we often highlight our personal and intimate stories—those that come from our families, our surroundings, and our lived experiences. For me, this brings a sense of honesty; I try to express myself through what I have lived.

This is why I began painting subjects that might seem unusual in the context of life in Gaza, like animals. When people see my work, they are often surprised to learn that I live in Gaza. I have been painting for over twenty years, and many assume I must live elsewhere to create such images. My colorful animals come from a personal story rooted in my childhood. When my grandmother passed away, my mother inherited her goats and sheep, and as a child, I was the one who cared for them, feeding them and giving them water. That bond stayed with me.

As I grew older and became an artist, I never forgot that time, because I loved it deeply. Today, I paint these animals in bright colors, with the imagination of a child. These are the colors of my own childhood.

DM: The subjects I paint do not stem from imagination, they are stories I have lived. Many of my paintings speak about fishing and fishermen, and these are not random figures; the people in my paintings are my family. My grandfather was a boat builder on the shore of the Gaza Sea. He used to build large wooden boats, about eighteen meters long. I remember watching him as he worked, going with him to the beach, to the shore. Their house was big, and he used to build the boats inside it, they had a large courtyard where the construction took place.

These things are not imagined; I witnessed them as a child. I remember my grandmother bringing food to my grandfather and the men working with him so they could have lunch or breakfast together. I also remember when they would go fishing and bring the fish home; the fish were so colorful. This is something I also wanted to highlight in my paintings.

When I married Mohammed, my family was living in a coastal area by the sea, in the Shati Refugee Camp. But when I married him, Mohammed was living in Al-Bureij Camp, which is located in the center of the Gaza Strip. The house we lived in for about twenty years was surrounded by land full of olive and orange trees, and wells. That environment also deeply influenced my work, it is something I always try to bring into my paintings.

In Gaza, people often say that you can tell where someone comes from by the food they eat and the bread they make, because each region has its own distinct traditions.

Growing up by the sea is very different from growing up in the center, there is a big difference. This stems from the fact that neither of us originally comes from Gaza, even though we were both born there. Our families are from different villages; both displaced in 1948 and eventually settled in the Gaza Strip.

My family originally lived by the sea in Asqalan. After 1948, when they were displaced to Gaza, they settled once again near the coast. Mohammed’s family, on the other hand, had a different background, they were farmers who worked the land, cultivating olives and oranges, and they have continued doing so until today. Even now, some of Mohammed’s relatives still work in agriculture and farming near Gaza and Be’er Sheva. These aspects are very important, and it’s essential for people to know about them.

EJ: It’s another kind of history that ends up being erased in this whole process. Displacement on top of displacement, on top of displacement, on top of displacement…

MAH: As Palestinians, when we are displaced from one place to another, we try to carry our culture with us everywhere. For example, Dina’s family or the people from al-Majdal who brought with them the loom, the old technique they used to weave rugs and carpets. Or Dina’s family of fishermen who came here and continued to fish, preserving their craft. The farmers too kept their traditions. This is also part of what Sara is referring to in relation to the exhibition—the idea of materiality.

EJ: We have Palestinians who were exiled under the British, others in 1948, and others again in 1967. Across generations, we’ve built an international body of knowledge: Palestinians who already know what it means to live in a foreign country, to raise children alone, to rebuild a life, to return, to send remittances, to rebuild, to survive and so much more. Yet the international system of structures that keep us apart prevent this crucial knowledge from circulating, blocking the most valuable resource our community holds at this moment—us.

This point concerns another work in the exhibition, We Ate the Wind. This work explores transnational forms of belonging, kinship, and visibility—the experience of family separation and fragmented communities. This experience that the people of southern Italy went through deeply resonates with the Palestinian experience, which may be why I felt so attuned and at home to that rhythm of coming and going that defines life in the Salento.

[1] The title refers to the chapter Material for a Film by Elio Petri and Ugo Pirro in the book Per un Palestinese: dediche a più voci a Wael Zuaiter (1984), written by Wael Zuaiter’s former partner, the Australian artist Janet Venn-Brown.

[2] Founded in 2014, Dar Jacir for Art and Research houses multiple projects grounded in shared encounters and hospitality. Dar Jacir is an interdisciplinary experimental learning hub that fosters cross-cultural and intergenerational exchanges. A process and practice-oriented platform, it is devoted to educational, cultural, and agricultural exchanges and productions for the Bethlehem community and beyond. Through a participatory approach, collective knowledge is created, experimental new works are produced, and structures for care and repair are fostered. Dar Jacir is the only artist-led space in the Southern West Bank that provides arts education and residency programs for both Palestinians and internationals, operating across visual arts, sound, cinema, performance, dance, literature, and agriculture. Together with its diverse community of artists, farmers, researchers and cultural workers Dar Jacir brings together a broad public that is deeply involved in community activity and collaboration in a particularly shattered territory. Intimacy is at the heart of the project. Artist-led and women-led, it facilitates and gives agency to artists and participants to lead, ask questions, and encounter international and local artists, thinkers, and cultural leaders.