The Ghosts of Italian Colonialism

The case of the former Museo Coloniale and its dismembered collection: a conversation with Leone Contini

Museo Fantasma (Ghost Museum) is the title of the workshop led by artist Leone Contini at NABA – Nuova Accademia di Belle Arti from September 22 to 24, in the framework of the Hidden Histories 2021 program. During the three days the artist will present and discuss the case of the dismembered collection of the former Museo Coloniale, a fascist institution inaugurated in 1923 at the Palazzo della Consulta in Rome, which derives its first nucleus from the Erbario e Museo Coloniale previously founded at the Botanical Garden of the same city in 1904. After going through several changes of location and name, the former Museo Coloniale was finally closed in 1971, and its collection scattered and hidden in the halls and storerooms of various museums and institutions of the Capital.

Contini has studied this story for many years, and has now decided to propose a moment of collective and shared reflection on the topic, in order to question the meanings, implications and violence of ethnographic collections and the amnesia of Italian colonialism. The following conversation retraces the motivations and paths of his research, introducing the objectives and intentions that will structure the workshop. It also provides a broader view of Contini’s practice, which lies halfway between artistic disciplines and anthropological work.

Hidden Histories is a site-specific public program, consisting of performances, workshops, talks and urban explorations, meant to reflect on the cultural and historical heritage of Rome from a decolonial perspective. Conceived and curated by LOCALES, a curatorial platform founded in Rome by Sara Alberani and Valerio Del Baglivo, the project presents this year its second edition, running from June to October and including interventions by Stalker, bankleer, Josèfa Ntjam, Leone Contini, Daniela Ortiz and Adila Bennedjaï-Zou. As the program unfolds, a series of interviews conducted by Marta Federici with the artists of HH 2021 will explore their research and provide a broader context for each.

As you have previously stated, your research borderlines between creative practices and ethnographic work, indeed, your path sets off with cultural anthropology and philosophy university studies. In what ways has this training influenced your work as an artist, specifically in the choice of the themes, and in the definition of the methodologies?

I believe content is what’s most relevant when it comes to my academic background. Envisioned communities, decolonization processes, the genesis of nationalisms, the birth of nation-states and so on, are all themes I came across in my university career and have protractedly remained separate from artistic practice. My academic years were those of the Social Forum, thus I had access to these topics not only through the university, but also in more activism-related settings such as that of Genoa in 2001, and the 2002 Social Forum in Florence. For me, that was a moment of political and cognitive effervescence.

On the other hand, the issue pertaining to methodologies is more multifaceted. We often expected anthropology to offer very specific methodologies, yet there are many different approaches, and they often contradict each other. Nevertheless, the predisposition and interest in interacting with other human beings is unquestionably an example of attitude embedded in the kind of anthropology I carry with me. It is usually referred to as fieldwork: an intense, assiduous, prolonged interaction with a community – with the omnipresent awareness that communities are made of individuals. Furthermore, anthropology deals extensively—though never enough—with cultural appropriation, i.e., the appropriation of somebody else’s discourse, speaking out on behalf of the other. This is yet another aspect that belongs to my artistic practice. Nevertheless, we must not forget that ethnography develops along with the processes of colonization, which is ultimately its original sin. Reflexivity is indispensable.

For Hidden Histories 2021 you will present a talk and a workshop dedicated to deepening the case you have been studying for several years, of the former Museo Coloniale, an institution founded during the Fascist era in 1923. When and why did the research on this collection come about? How have your artistic intentions and motivations evolved over the years?

To answer that, I must go back to 2001/2002. Those years mark a watershed in my research career: while I was studying anthropology and approaching postcolonial themes for the first time, I was also interviewing my grandmother, for I started to sense the problematic nature of family stories about Libya. Mine is not a nostalgic family, and back then I only vaguely knew that there was a history in Libya that involved my great-grandmother, my grandmother, and my mom, who was born in Tripoli. I wanted to understand more. I was beginning to understand that colonialism had been a monstrous thing; in those years people were beginning to talk about Italian crimes in Libya and Ethiopia, and to me, it seemed like there was an incongruity between my grandmother’s being a socialist, her critical attitude towards power, and this family narrative in the background. I began to get her talking to me, even just anecdotally, on how she positioned herself with respect to that situation which was becoming increasingly clear as a historical crime. I wanted to understand how I too, should and could position myself. I realized that my very existence was connected to crime.

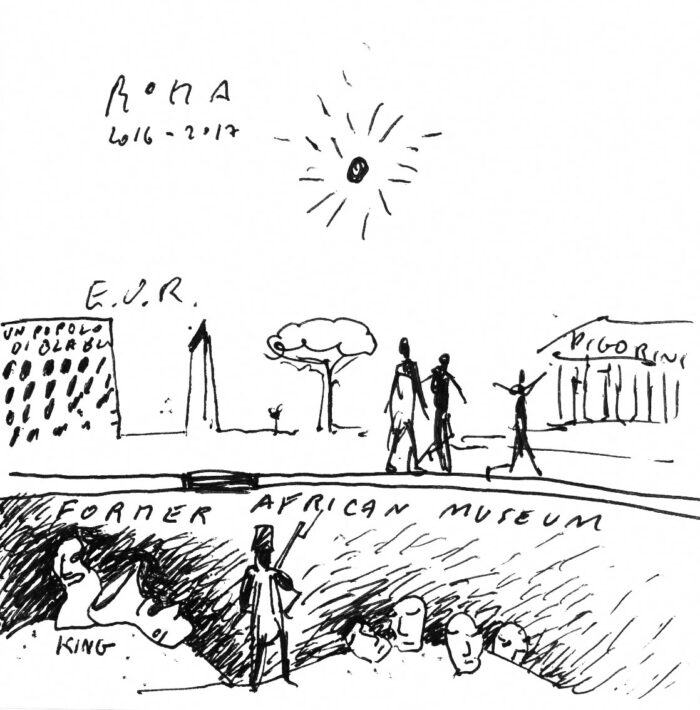

The footage I shot at that time remained unused for many years, until in 2016, I was contacted by Arnd Schneider, an anthropologist who invited me to co-participate in the European project TRACES: Transmitting Contested Cultural Heritage with the Arts. Initially, we wanted to find a connection between the migrant communities present in Rome and the objects preserved in the ethnographic collection of the Museo Pigorini, but then one day, while we were in the office spaces, which are closed to the public, I noticed a plastic model of Sabratha, covered by a cloth. The model is part of the dismembered collection of the former Museo Coloniale, whose history thus began to emerge before our eyes. At that time, the museum was in a transitional phase, it was still under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and not the Mic [Ministry of Culture], and it was not clear what its destiny would be. This institutional paradox immediately caught my attention: it was a ghost collection, which both existed and yet not.

It is important to clarify that from the very beginning, the former Museo Coloniale was marked by a clear propaganda dimension, there is a very strong component of violence that structures it which becomes very explicit in the objects that are part of its collection. We realized that these objects had been scattered in various places after the official closure of the institution in 1971, so we went searching for the different components of this body which had been dismembered and hidden, as if to hide the traces of an original criminal act.

The work done with Arnd was then used in the exhibition I did at the Museo Pigorini in 2017, entitled Bel Suol D’amore – The Scattered Colonial Body. Thanks to that project I was able to start focusing on some pivotal points, which I then expanded during the following years: I wrote an essay for the magazine Roots Routes, took part in the Resurface Festival after Giulia Grechi’s invitation, and presented a performance, again at Pigorini, which is yet another stage of the same path, I also worked with video, reworking and editing different material I had collected over the years. Presently, the workshop for Hidden Histories represents the last and most recent stage of this research.

Can you tell us something more about the workshop? What are the intentions and objectives that will guide the work proposed on this occasion?

It will not be a pedagogical workshop with a frontal approach. I will obviously share my experience with the museum collection, but participants will also be encouraged to share their own views and try to imagine a strategy to detoxify the objects of that collection. Obviously, in order to orient the work, it will be very important to understand the composition of the group, and who will be present.

Already during the first phase of our research with Arnd, I had felt the need for a workshop, something that at that time did not take place for various reasons. Back then, the work was focused on those who today are the descendants of the Italian colonizers—a relevant aspect of the question, akin to Italian studies, and tangent to Arnd’s area of research. However, there had not been a moment of confrontation with second-generation people, the Afro-descendants, so this workshop is an opportunity to insert a component that I felt was missing.

I’m interested in trying to observe these objects from different points of view, together with people whose backgrounds are different from mine, who come from the other side of that watershed that divides those who have colonized from those who have been colonized. In general, I believe that the encounter with other subjectivities is fundamental when it comes to research paths of this kind. In front of these objects, in front of their weight and their violence, it is essential to develop a choral approach, together with the ability to know how to listen.

“However, the ethnographic-museum device cannot escape its original sin of colonial robbery of the Other for the (undeclared) use of Western self-edification.” These words you wrote in 2016, following your first visit to Museo Pigorini, hint at the necessity and urgency of re-acknowledging ethnographic museum collections as direct expressions of colonial violence. Starting from this assumption, how can this kind of place be given meaning today? I am thinking of the fact that just over a year ago, the Museo delle Civiltà announced its intention to reopen the former Museo Coloniale, with a new layout and a new name, “Museo Italo Africano Ilaria Alpi”. An extremely complex and delicate operation.

All museums and ethnographic collections are problematic and irredeemable and should not exist. We know very well that almost all the objects conserved in these places were acquired in a context of totally unbalanced power and in most cases should be returned. From many of these museums, there is usually a kind of cosmetic attempt to justify their existence. For example, the names of these institutions almost always celebrate the diversity and equal dignity of human cultures, but in reality, they are places that base their existence on the plundering of other societies, which have been despoiled of objects fundamental to their symbolic and material life.

The case of the former Museo Coloniale is somewhat special because it is not the averagely violent ethnographic collection, but an exceptionally violent one, created with clear propaganda intentions in a colonial and totalitarian context. Inside there are many objects that due to their nature, would normally not be part of an ethnographic museum: modern firearms, works created by Italian artists traveling with the invading armies, classical busts, and busts of war criminals, etc. It is, by all means, a museum of Italian colonialism, it has been from the beginning, and in my opinion, it should continue to be considered as such—obviously, however, with a reversed meaning: it should become a museum of critical reflection on Italian colonialism. In Germany, there are museums on Nazism, while in Italy there is no museum on fascism or colonialism. We must ask ourselves why the need to critically narrate that past has not yet been felt here. Therefore, coming to the renaming question, I personally would have redefined this museum as the “Museum of Italian Colonialism in Africa”.

In any case, this collection should be viewed with great caution and should be contextualized as its rearrangement presents several risks. I have a lot of faith in the people who today have decision-making roles in relation to these collections, but in twenty, fifty or more years, we don’t know what could happen. It’s an inherently dangerous museum, so our responsibility now is to clearly define a perimeter of usability.

I would like to return to the 2017 exhibition, Bel Suol d’Amore – The Scattered Colonial Body. On that occasion, you proposed a reflection on the history of Italian colonialism in which your family’s experience and personal stories had an important weight. Could you tell me something more about the dynamics of interaction between the public and private dimensions of memory within the works exhibited?

In that exhibition, I simultaneously worked on both public and private memory, trying to create a friction between two dimensions that sometimes don’t want to be close. My grandmother died in 2010 and I’m sure she would not have approved her 2002 interview being set up a few meters away from the bust of Graziani, a war criminal she detested. At the same time, however, her family lived in Libya, which had been militarily invaded by Italy. My grandmother herself remembered the disembodied heads of Arab leaders displayed as trophies on the jeeps that roamed the city of Tarhuna, where she lived. There is always a strong connection between the private and public dimensions of memory, even if the former can never be reduced to the latter. It is a typical aporia of the tragedy: one finds oneself suspended between a condition of guilt and a condition of innocence. However, this innocence brings within a dynamic of self-absolution that is problematic and characteristic of Italian colonial memory: in Italy we always try to recount the colonial past in a self-absolving, inoffensive way. At that moment I felt the need to enter right into the physical, microscopic dynamics of Italian self-absolution and I did it starting from a private experience, trying to short-circuit it with public history, to break the family narrative, which is always partly self-absolving.

I think it’s important to bring these two dimensions into conflict, even if it’s sometimes painful. For me, it has been a very uncomfortable job at times. In addition to my own family narratives, I came across those of the Italian-Libyan community, often openly nostalgic. However, the term Italian-Libyan should not be used, because it is somehow a self-definition… which is why, going back to the previous question, the term Italian-African is also problematic. In my video, I had initially used the phrase “Italian-Libyan”, but then removed it, because it totally aligns with their point of view—in anthropological jargon, we could say that I fell victim to an “emic” perspective. The emic view, which is opposed to the ethical view, is that of the anthropologist who “assumes for good” the account of a community without subjecting it to articulated analysis, factual evidence, and judgment. The danger of an emic approach with a community of former colonizers is high, one risks repeating a self-absorbed narrative that instead needs to be defused.

As you have clearly said, here in Italy, the history of Italian colonialism remains unfortunately mostly hidden or sugarcoated, certainly not sufficiently questioned. Do you think that artistic practices can stimulate concrete changes in this regard? What is the space for action and that for encounter, what are the possibilities or responsibilities of those who work in the art and cultural field? What is the relationship between art and other disciplines, such as historiography?

What is interesting about artistic practice is that it allows you to analyze the question from different points of view; you can choose to bring to light a different nuance, the one that pertains to you and to which you have access. The artist tends to be able to engage in a kind of operation that restores capillarity, body, affectivity to these kinds of issues, while the historian’s operation is more one of truth, or at least it should be. Even the affective, aesthetic gaze, typical of artistic practice, is a cognitive type of gaze, but if it is not developed within the furrow traced by a historian who has studied the facts more analytically, proving their truthfulness, it risks unconsciously corroborating an emic narrative, getting lost in a partial representation that is mistaken for reality. In my opinion, it is fundamental for the artist to follow clear lines, in order to place themselves under an explicit ideological umbrella. Precisely because art works with nuances, with contradictions, there is a constant risk of going off track to fall in love with some phenomenon and celebrate its beauty. This is another reason why it is important to have a choral approach: within a chorus each person can tell a facet of reality.

I truly envy the approach taken by anthropologists and historians and how their work is always intertwined with the work of others. For example, when you write a scientific article you refer to a bibliography: the more you root what you write in the work of other people, the more valuable that article becomes. In the art world, on the other hand, there is often an obsession with originality: there is a lot of competition, artists are expected to be unique, not to work as a team within a shared horizon of practices, as it happens in other disciplines. There is still this romantic idea of the solitary artist-genius.

The Hidden Histories program stems from the desire to question our art-historical heritage and the notion of cultural heritage in order to initiate processes of decolonization of the knowledge we share and of our imagination. What does “decolonize” mean to you? How do you interpret this verb?

I believe that decolonization should start first from ourselves and our gaze on reality. Decolonizing for me means cleaning or refocusing the filters through which we observe reality. Each person is born and then, in the process of enculturation, progressively adds a series of filters in front of their eyes: in the end, what you see through all these filters is you. We all need to detoxify our gaze, there are many legacies of colonialism that still condition us in some way, even if we are not aware of them.