The Erotic and The Sacred

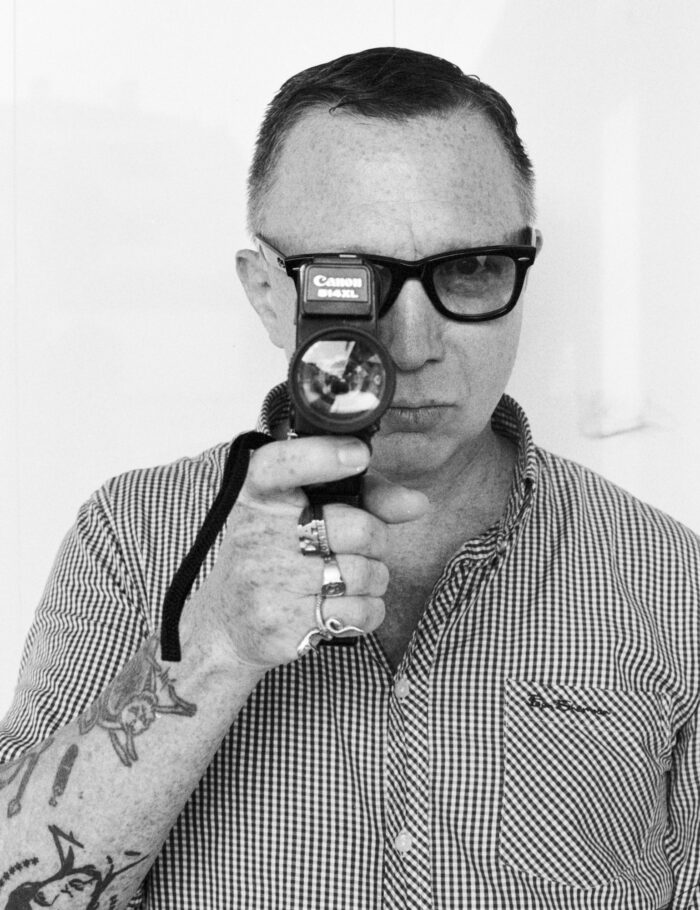

Bruce LaBruce in Naples

Thirty films under his belt and no intention of softening the blow: Bruce LaBruce continues to subvert bodies, genders, genres, and ideologies with the same ironic fury with which, in the 1980s, he invented queercore—an explicit yet political porn, a radical aesthetic defying all normalization. Filmmaker, photographer, fanzine writer, dissident, LaBruce has combined porn, agitprop, and poetry, turning the obscene into an art form and provocation into an act of resistance.

I meet him in Naples, where he has just wrapped shooting his latest film, and the contradictory energy of the city, where the erotic and the sacred coexist without asking permission, seems the perfect match for him.

Jacopo Gonzales: How did the idea of making a film in Naples come about?

Bruce LaBruce: The script is based on Gian Maria Cervo’s work L’uovo. It’s an experimental piece that has specific references to Naples and the idea of it as a vertical place, layered in the past, from Virgil to the queer history of the city.

How did you prepare for it?

Before Gian Maria contacted me I found a book in a bookshop called “The dreadful short life and gay times of John Horne Burns. He was a gay American writer who was stationed here during the Second World War and he wrote what was considered a classic of queer literature. It’s set when the Galleria Umberto I was the heart of the city and all the soldiers went to this famous gay bar called “The mother”.

Burns was an interesting character ahead of its times, in the novel he really gets into all the camp language of the people and tells how the gays were integrated into the military.

The gallery describes Neapolitan daily life and all the details that I can still recognize in the culture of today, and even though the Galleria is now a ghost shopping mall, the city itself keeps its old spirit.

What impresses me of Naples is that, as opposed to most cities in Europe, it is not xenophobic at all, it’s very much friendly to outsiders.

Can you tell me something about the movie?

The other thing I saw before coming to Naples was Il mare by Giuseppe Patroni Griffi, and I got obsessed with this movie so much that I asked Gian Maria to do an experiment, take his play and match it with the movie. The work from which I adapted the script is a monologue played by one character, but I decided to keep the main three characters of the film. It’s kind of a conceptual piece grounded in the narrative board of Il mare.

Il Mare has a clear homoerotic subtext. Did you make a more explicit and queer version of it?

I would say it’s more about the spirit of the city, it’s not really queer identified per se. I took that as a part of what strikes about Naples, which is for me a discreet but openminded sexuality. The film has a queer edge to it but I wouldn’t say it’s a traditionally queer movie.

And it’s not a porn movie for a change, which is very refreshing for me, even though a lot of queer people are not happy when I make this kind of movie because they want something more gay and explicit.

Do you feel your audience has changed over the years?

Nothing has really changed for me in a way, I’m generally alienated by the gay mainstream.

Was it always like this?

In the 80s I turned to the punk scene because we thought that the gay and lesbian mainstream—but the gay especially—was racist, it was a conformist white middle-class movement and politically not very interesting.

It was more interesting in the 70s when the gay liberation movement had a Marxist approach. In Toronto the free magazine you would find in the gay bars was a radical Marxist magazine where a very famous film critic started writing very political gay critiques of films with a Marxist and feminist edge, he was a huge influence for us at the time.

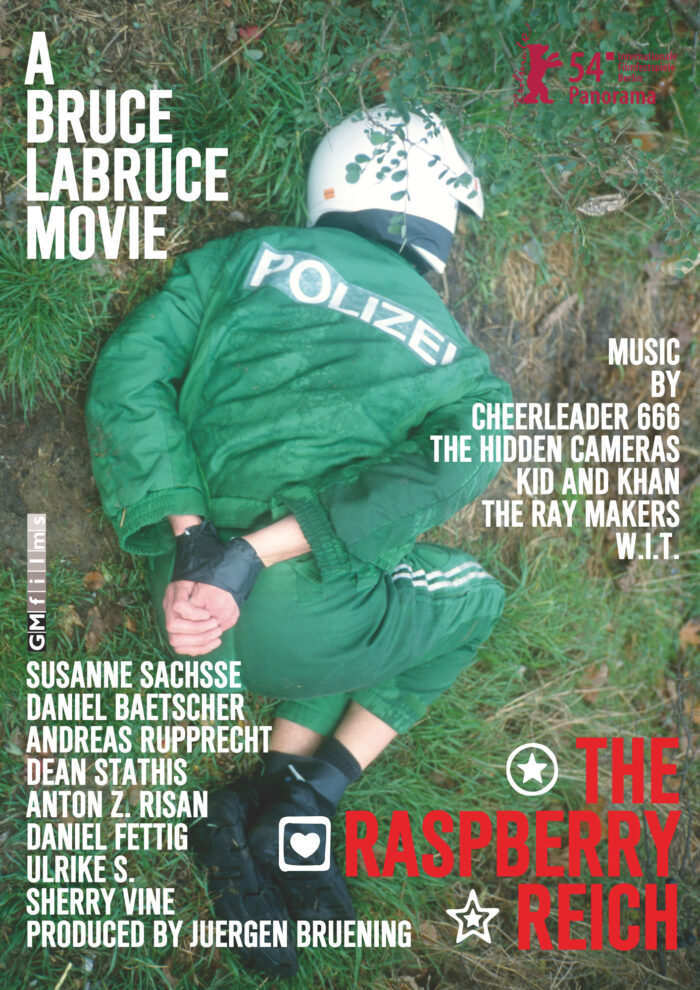

Then when the punks turned out to be homophobic and sexist we started making our own stuff. We would find images of gay porn and collage them into fanzines and that was my first experience in making political porn, or what I consider porn for political purposes, which I persist to do to this day. Like a character says in my film The Raspberry Reich, there will be no revolution without sexual revolution, and there will be no sexual revolution without homosexual revolution.

That felt like a critique of the left…

Yes it was a critique of the radical left which I also continue to do. For me the homophobia of the right is easily identifiable and way easier to fight because it’s so apparent and such an easy target in a way. The kind of tolerance of the left though for me is even worse, this idea that it is ok to be gay as long as you are well behaved and you are not too flamboyant. The fact that the movement had to dissociate itself from us as that inconvenient element that didn’t fit into their agenda, that was the root of my very first movies. The conflict was about characters who had homosexual sex but were not gay identified, they were skinheads, prostitutes, extreme left-wing revolutionaries who were using homosexuality just for a revolutionary purpose. The fluidity of sexuality and challenging the idea of a fixed sexual identity ruined the left on a certain level. This idea of having a fixed ideological position about homosexuality has made in some way the oppressed become the oppressors in terms of gay mainstream.

Do you think there’s still a need for a gay anti-establishment point of view?

I do, but I think it’s become sort of lost. The left has become very fractionalized, and parts of it are now so politically correct about the proper way of representing gays lesbians and trans. My film The Misandrists, which was an affectionate critique of feminism and for me very pro-trans, really divided people. It’s really almost impossible to have any kind of solidarity because each one has a different idea of what is politically correct and how to represent the body in general. Also, I think the assimilation movement was a big mistake, as people have lost their kind of core as opposed to what they were fighting for in the first place. The engine of the gay movement in the 70s was radical sexuality and experimentation, challenging conventions about sexual behavior, it was not conformist as it is now.

People forgot how the whole liberation movement started in the first place, it seems like everything it’s super capitalist now, all corporate sponsorship.

Where do you situate your audience in this scenario?

In the last fifteen years the main queer festivals rejected my movies. They think I’m a bad gay cause I’m doing the gay movement a disservice by doing these not politically correct representations, but I think I carved a niche of my own. The Visitor started as a project I thought could never go anywhere as it’s extremely pornographic, but in the end it premiered at the Berlin film festival and was programmed at so many other festivals. I feel there’s very few pornographic films that get this kind of public attention.

How is it like to be an independent filmmaker today?

When I was studying at the New York University we had to be multidisciplinary and we all participated in each other’s projects. In the meantime in the punk scene we made fanzines and short experimental films, we were photographers, writers, we wrote manifestos, we did comic books and situationist détournements. It was all underground, pre-internet, pre-social media, so to get our work out there we had to learn how to distribute and promote ourselves, and that multidisciplinary spirit and ethos of working has always stayed with me. I learned to do it all by myself and it really stayed with me. To me the best thing that can happen is when work doesn’t seem like work, like a hobby or something that I just like to do. I can make a multimillion dollar movie or a fifty thousand dollar movie, it doesn’t matter, I put the same amount of effort into it. I’ve been making bigger budget movies and waiting so much time to get financed—I did that for Gerontophilia and it took forever to make it. So I decided in the meantime to take small projects like The Visitor in London or this one in Naples, sometimes they turn out to be more interesting than what was planned. I’m always looking for that perfect project that comes out where I can have complete artistic freedom, it’s very rare but it still happens.