Between the Cave and the Cosmos

Le Nemesiache’s Eruptive Creativity

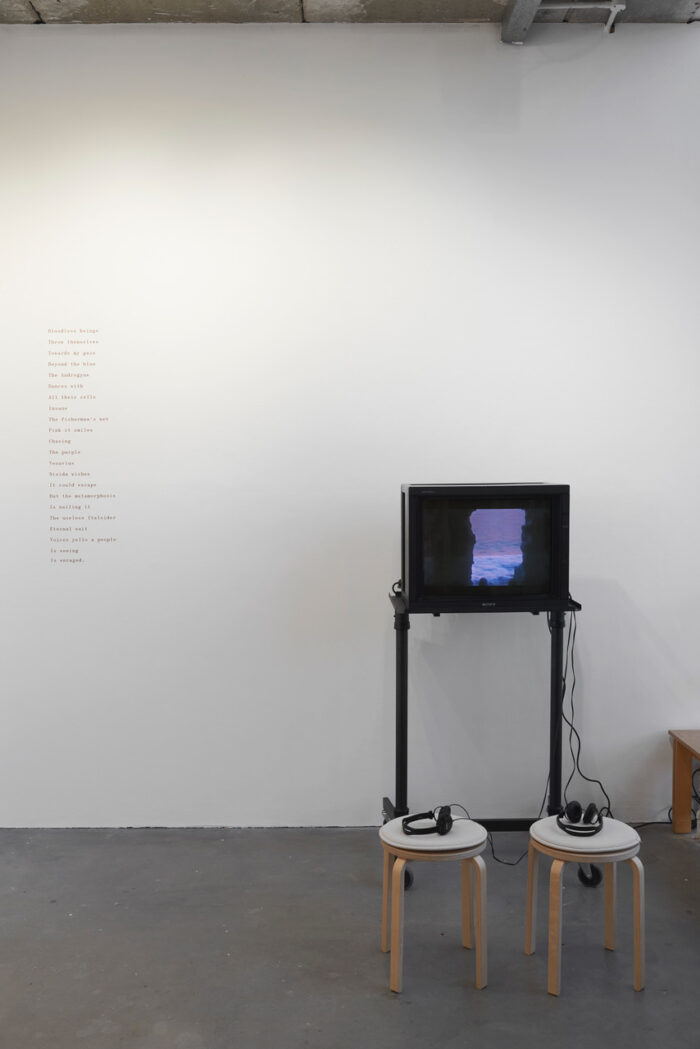

Curated by Sara Guidi, the project Our Truths Flow Together With the Waves aims at exploring the concept of self-image in relation to landscapes, focusing on the intersection of gender and identity. It draws inspiration from the artistic path of the Nemesiache, a feminist-artistic group based in Naples since the 1970s. With exhibitions, workshops, and a series of texts published here and written by Giulia Damiani, Sonia d’Alto, Mattias Gimigliano and Sara Guidi, the project’s research is centered around the exploration of women condition as a cosmos, explored through various artistic mediums such as dance, music, rituality, and poetry. Our Truths Flow Together With the Waves – Chapter I was hosted at the Italian Cultural Institute in Copenhagen from July to August 2023. Our Truths Flow Together With the Waves – Chapter II opens at Casa Morra – Archivi d’Arte Contemporanea in Naples on October 19th and runs until November 15th.

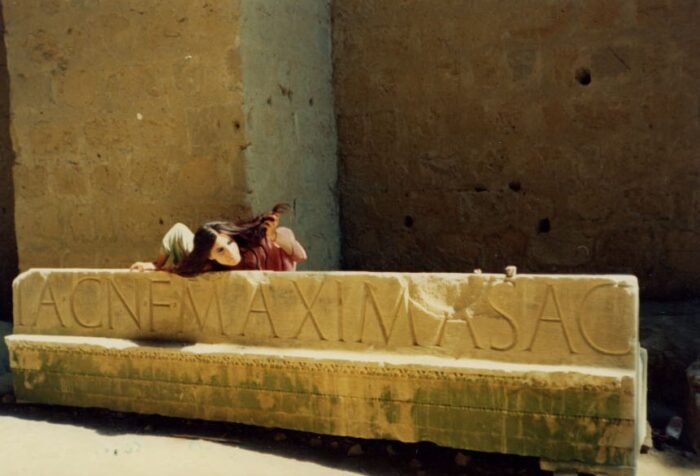

We are heading towards a tunnel. To what once used to be the seat of the great Cumaean Sibyl near Naples. Today this cavern on the mainland in southern Italy preserves the structure it had during its time as a Greek colony. The tuff rock, made of volcanic ash, is punctured by several openings on one side. In the Aeneid, Virgil described these openings on the cave as the Sibyl’s “hundred mouths.” The prophetess visionary words thundered out from the inner chamber of the grotto. The enquirers who visited the cave for a consultation listened sitting down in the outer chambers. The prophetess’ utterances were said to be teasing and evasive.

The seat of the Cumaean Sibyl was pivotal in the work of the feminist group Le Nemesiache, who lived and worked in Naples, about fifteen miles from the cave. Their 1977 short film Le Sibille (The Sibyls), which Teresa (my guide to the tunnel) took part in was shot around this area. In the film the artist Lina Mangiacapre, Teresa’s sister and the founder of Le Nemesiache, narrates a seance and the scenes of women dancing on this land: “You’re not alone, other stories are buried in the water, fire, in the soil, in the air. […] We are in Cumae, the Sibyls’ territory. Through the stones, we’ll need to find ourselves again.” [1] Mangiacapre’s words echo the experience of another member of Le Nemesiache, Cassandra. In a pamphlet from 1973, Cassandra recalls visiting the cave on her own to consult the oracle. She writes how accessing this place meant to descend down into the underground, to hear the voices of women from the past, including the poetess Sappho. In Cumae she saw the long-forgotten women and from the underground they came back to the world together to tell their stories. [2]

Over the years of working with Le Nemesiache I’ve understood Cumae as a liminal zone, a threshold, which can help make sense of their multilayered relation with landscape. Connecting with the depths of the earth, bringing back women’s prophecies and their forgotten stories, Cumae is one of the energetic nucleuses in Mangiacapre’s feminist vision. Hers was a plan for the re-appropriation of a place, historically imbued with natural phenomena, myth and magic, but which was being progressively destroyed by men’s capitalist exploitation. In Mangiacapre’s view the alleged break between nature and culture, fuelled by patriarchy over the centuries, was to be reconciled by feminist creativity. [3] Le Nemesiache’s interventions in landscape were mediated by their feminist creative commitment. As the quote below highlights, their experimentation was linked to the body and extended into their environment.

“We claim back women’s bodies and the body-territory of our city.” [4]

In one of their manifestos Le Nemesiache express how their performances were meant to bring about a different historical dimension, making it “real”. [5] This was achieved by appropriating mythic stories, such as the story of the Cumaean Sibyl, and through the embodiment of these by the participants. For example, in The Sibyls the group visits the cave of the prophetess while with their dances and gestures they evoke their suffering. Le Nemesiache’s consciousness-raising method which they called psicofavola (the psycho-fable) embraced mythological imagination and the forgotten pasts on one side, and the body and the performers’ actions on the other. The ultimate intention behind this practice, the realisation of a reality different from patriarchy, implied an on-going evocation of other spaces and times; this other space-time grew from a condition of oppression – in this case women’s oppression – but it never settled into a definitive dimension, such could be a binary notion of gendered identity. Rather than considering here the group’s productions in theatres around Italy between the 1970s and the 1980s, I return to their relation with landscape: what they call their body-territory. I believe that to understand the psycho-fable and Le Nemesiache’s production at large, we need to look at how the the psycho-fable and its gestures experienced and re-invented the body-territory.

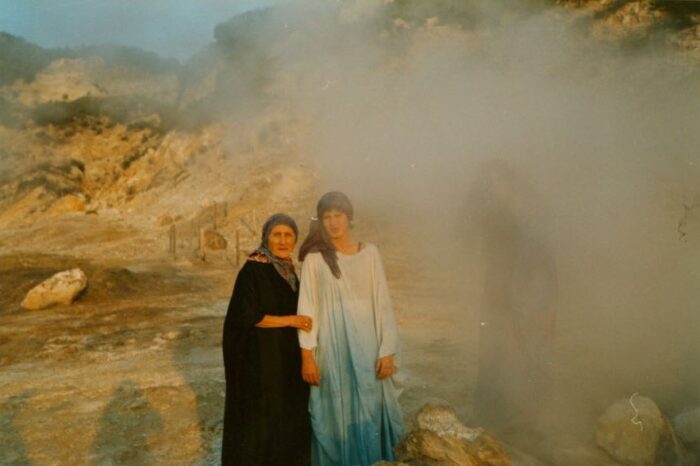

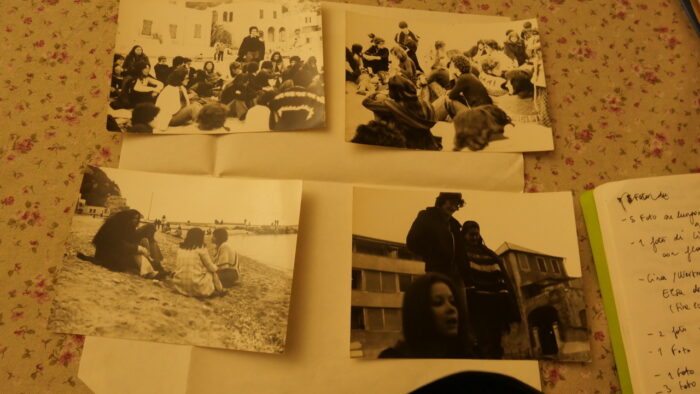

In an article from the late 1970s on the Phlegraean Fields, Mangiacapre affirms: ‘my research endeavours to reconstruct the myths, the old rituals, and to track down all the possible documents on the historical connection of the Sibyl’s origin, Cumae and the Phlegraean Fields’. [6] The Phlegraean Fields is a large volcanic area situated to the west of Naples, close to the cave of the Cumaean Sibyl. The fumes from its craters cover much of Le Nemesiache’s archival documents and original actions. The Sibyls constantly returns to this volcanic landscape; and the smokes are recorded in early photographs by the group, such as the one entitled ‘Psycho-fable in Naples’ (early 1970s). Judy Chicago’s Women and Smoke iconic series may come to mind here. Yet, while in Chicago’s photographs the barren landscape is altered by the artist’ pyrotechnics, Le Nemesiache’s actions were entangled with their real spatial and historical matter. The smoke from the volcanoes encounters the women’s renewed consciousness and their potential to act in the world. Humans and non-human landscape meet, and within this relation a liberating transformation seems to take place. Ethnographer Deborah Bird Rose worked on the concept of ‘permeability’ in her research on what she termed the emplaced ecological self, in other words the self that is materially embedded in specific places “as well as being consubstantive with the universe.” In her words “place penetrates the body, and the body slips into place.” Le Nemesiache’s permeable body-territory is a constant reference in Mangiacapre’s writing. In an undated document summarising her proposal for a total artwork the artist says: “I generate culture according to nature, that is according to reality; my reality, the reality of my cells, of my roots, of my body, of my hair, of trees, moon suns, galaxies.” [7] Le Nemesiache’s work seems to be situated at the porous juncture between body and place; and specifically this juncture became the site for the expression of feminist creativity and the realisation of a different reality.

Within such sensuous dialogue with their landscape, I’ve understood ritual and performance as encapsulating the psycho-fable at its core, allowing members of the group to reveal themselves as creative agents. Art critic Lucy Lippard traced the commonalities between the rituals by women artists in the 1970s and the structures of the Women’s Liberation Movement, including consciousness-raising and leaderless meetings. [8] Rituals were used by artists to marry the public with the private again, a trajectory much emphasised by the second wave feminist argument “the personal is political.” Lippard summarised women artists’ production in the form of ritual as such: “Ritual and ritualising, or conceiving art-making as a ritual process even if the final product is not advertised as such, are an attempt to reinvest art with private and public meaning. Art, like ritual, can be defined as formalizing one’s experience to make it familiar (old) at the same time it is being renewed.” One of the core elements of ritual as an artistic form that emerges in this quote—and in the work of artists outlined by Lippard, such as Miriam Sharon and Mary Beth Edelson—is the intimacy created by the renewed relationship between private and public; and another element is the transformation at work in rituals, which make “one’s experience familiar (old) at the same time it is being renewed.” A feminist take on ritual suggests that an inner and outer transformation was necessary in order for women to eradicate patriarchal references from their individual lives and the collective life. New references, including prophetesses, goddesses, sirens and witches—and also natural elements such as stones, fumes, lava and cliffs—were introduced to challenge the patriarchal assumptions behind what is believed to be “normal”, professional and neutral in art production and culture. These identities were taken up not with a sense of nostalgia for an ancient past, but with an imaginative project to retell these ancient stories in the present and to create new references for the future. The individual mission to become one’s own feminist self was married with a collective impulse to redefine the framework in which women make art and think about history at large.

Beyond its story-lineThe Sibyls records the ritual coming together of members of the group. Returning to the landscape of Cumae repeatedly over the years meant both invoking the Sibyl’s presence as well as new interpretations across Le Nemesiache’s individual and collective experiences. During their ritual dances, within their shared vocabulary of gestures, a delicate energy circulated among Le Nemesiache women. Many of the scenes from their films, including The Sibyls, simply record the intimacy and intensity of the members’ bond. Feminist scholar Catherine Clement described how two paradigmatic female figures, the hysteric and the sorceress, expressed themselves in secret play. Perhaps by watching the films by the group, we’re experiencing their secret play. Clement referred to the body of the hysteric and the sorceress as a “theatre through which beastly signs and marks can be revealed to oneself and erupt into the outer world.” Bodies can be intermediaries, props, passages towards an outer eruption.

In the 1970s bodies as theatres of revelations could finally support women in the project of self and collective realisation against their oppression. Such revelations had even older references. In her book After Sappho writer Selby Wynn Schwartz suggests a link between prophetic powers and acting. By interpreting and embodying godly messages ancient prophetesses were directly linked to the act of performing. Through the embodiment of empowering visions and through performance, women could realise their inherent force. In the case of Le Nemesiache there seemed to be a subversive eruptive energy at work in their channeling of the Cumaean Sibyl. The premodern disruptive importance of prophecy is analysed by scholar Silvia Federici in her study Caliban and the Witch. Federici reconstructs how the conception of the ‘body as receptacle of magical power’, which still prevailed in the medieval world, had to be denied by capitalist forces emerging with the bourgeoisie in order for the body to emerge as the source of labour power. The campaign against magic included prophetical charms. Federici argues that historically prophecies “have been a means by which the ‘poor’ have externalised their desires, given legitimacy to their plans, and have spurred to action.” Further on she explains how prophecy was replaced by the calculation of probabilities: the capitalist system needs regularity in order to perpetuate itself, thus it assumes that the future will be just like the past, and no major change or revolution will undermine this flow.

Both Mangiacapre and Federici critique the mechanisation of the body theorised by philosophers such as Descartes. Le Nemesiache’s psycho-fable opposed the view of the body as a means to an end. Rather, they wanted to open their bodies to be taken into another dimension, where they would show signs and wounds, express eruptions. [9] I want to finish by combining the conception of a permeable body, ready to absorb place while showing the signs of another space-time, with the embodiment of the Cumaean prophetess. Federici frames how prophecy was a powerful channel of desire and a spur to action. Le Nemesiache’s work shows their commitment to performance as preparation, as a gestural and verbal training for the coming of a feminist dimension. Figures such as the Cumaean Sibyl became ways to rehearse and ritualise the construction of an unpredictable reality. The prophetess belonged to a world which pre-existed capitalist extraction from natural resources and the automation of the body. Supernatural divination and magic appealed to Le Nemesiache, as these practices are based on the image of cosmos as a living organism, “where every element was in sympathetic relation with the rest.” Finally, ancient populations from the same area were said to identify divine prophecy with destiny itself, confirming the potential of prophecy to affect the course of time.

Through Le Nemesiache’s work I’ve come to interpret prophecy as a gestural and imaginative training. And what if we were to consider our bodies as prophetic bodies? What if we could let place be revealed into the prophetic body that continuously slips into place? And make of this convergence, of body and place, an inexhaustible potential; an ongoing ritual preparation for a reality that is different from the oppressive and ecologically consumed one we know? Le Nemesiache’s atemporal images keep on triggering desires for disruptive actions today.

Thanks to Reading Aloud, here you can listen to the audio version of this text.

[1] Mangiacapre, L. (1977) The Sibyls. 25 min.

[2] Cassandra (1973) “Acropoli di Cuma” (The Acropolis in Cumae). This was part of a pamphlet self-produced by the group, available from Mangiacapre’s archive.

[3] Mangiacapre, L. Opera Totale (Total Artwork). From a pamphlet in Mangiacapre’s archive, date unknown.

[4] The expression in Italian is “territorio-corpo”. From a 1981 pamphlet self-produced by the group, “MANIFESTO FEMMINISTA NAZIONALE PER L’8 MARZO 1981” (National Feminist Manifesto for the 8th of March 1981). Available from Mangiacapre’s archive.

[5] Cicli Iunari, cicli solari (Lunar Cycles, Solar Cycles) pamphlet available in Mangiacapre’s and Le Nemesiache’s archive, 1975.

[6] Mangiacapre, L. “I Campi Flegrei. Analisi e prospettive culturali di un territorio (Lettura e mito- logia)” (The Phlegraean Fields: Analyses and Cultural Prospects of a Territory. Reading and Mythology), in Mangiacapre’s archive, late 1970s.

[7] Mangiacapre, L. Opera Totale (Total Artwork).

[8] Lippard, R. L. (1977) “Quite Contrary: Body, Nature, Ritual in Women’s Art” Chrysalis, no. 2, 31-47, p. 32.

[9] From the pamphlet “Non solo figura di donna: follia come poesia” (Not just a woman’s figure) Rassegna del Cinema Femminsta,1979, p. 7. Available from Mangiacapre’s archive.