The Door to the Green Room

What comes before the work? What do the artist and the curator say?

The following is an ensemble of theoretical and descriptive fragments, poetry and documentation that deeper unfolds Julie Monot’s practice and latest work GREEN ROOM, curated by Elise Lammer for the research platform Alpina Huus, that was recently on view at Arsenic, Performing Arts Center in Lausanne. The quotes on theory are excerpts from German sociologist Georg Simmel’s 1909 essay Bridge and Door.

Context #1

Between January and September 2019, Arsenic, will regularly host exhibitions of visual artists concerned with the relationship between performance and domestic space. During this project, curated by Elise Lammer for Alpina Huus, the artists are invited to work across the various performance halls of Arsenic, challenging the notions of white cube and black box.

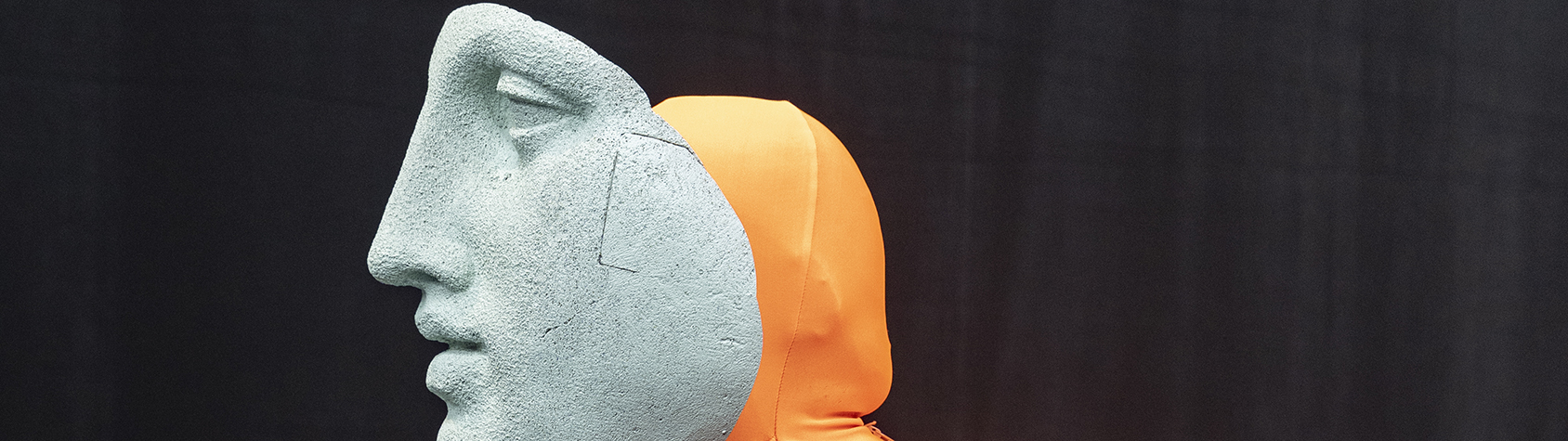

Alpina Huus x Arsenic. Julie Monot, GREEN ROOM, Installation view. © Julien Gremaud, Alpina Huus, Arsenic

Theory #1

“The wall is mute. But the door speaks. It is essential to man in the deepest sense, placing a limit on himself, but with the freedom to take it away again, of being able to go outside it. The finitude in which we find ourselves always borders in some place on the infinity of physical or metaphysical being.”

Proposition #1

The versatile aspect of a Green Room, which sits between the private and public realms, and the transitional quality of the colour is precisely what artist Julie Monot (born 1978 in Lausanne, where she lives and works) explores in GREEN ROOM, her first institutional exhibition in Switzerland. Transition sits in every element of the project, for which she produced over 15 anthropomorphic sculptures, as well as a series of scenographic devices. For Monot, transition is often a synonym of transformation, a topic she’s been exploring through numerous installations, videos and performances since 2013.

Mop (2018) at Alpina Huus x Arsenic. Julie Monot, GREEN ROOM, Installation view. © Julien Gremaud, Alpina Huus, Arsenic

Sujet

Julie Monot graduated with a Bachelor of Visual Arts from HEAD Geneva, and is currently studying at ECAL in Lausanne. She works across various mediums, such as performance, video, photography or installation. Her work focuses on the limits of corporeal externality and its modes of representation, among other things. Her appeal for transformation is rooted within her previous professional career as a makeup artist, and her experience in the field of the living arts.

Theory #2

“This work reaches its zenith in the construction of bridges. Here man’s will to union seems to be resisted not only by the passive separation of space, but also by an active, specific configuration. By overcoming this obstacle, the bridge symbolizes the expansion of the sphere of our will over space. Only for us are the banks of the river not merely in different places, but “divided.” If we did not link them together first in our aims, our needs and our imagination, our concept of separation would have no meaning.”

Golden Boy (2018) & Le Grand Objet (2018) Julie Monot, GREEN ROOM © Julien Gremaud, Alpina Huus, Arsenic

Sunset (2018); Muse Endormie (2018) Julie Monot, GREEN ROOM © Julien Gremaud, Alpina Huus, Arsenic

Dennis (2018), Golden Boy (2018) Julie Monot, GREEN ROOM © Julien Gremaud, Alpina Huus, Arsenic

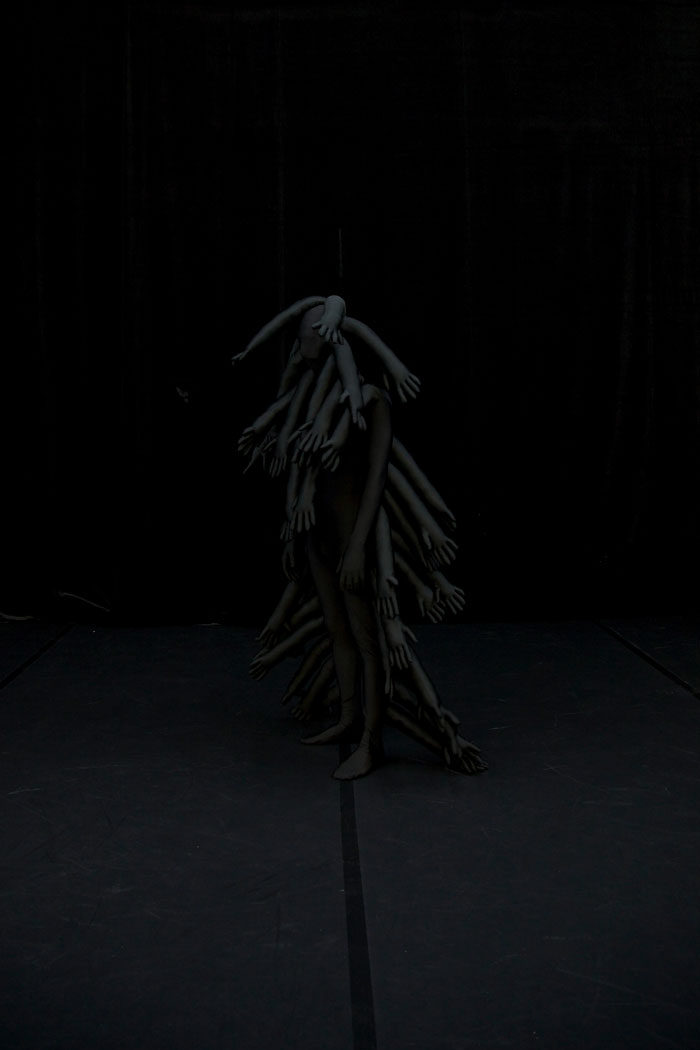

Réflexions du sujet #0

“Il s’agit d’une figure que j’affectionne particulièrement qui est celle du sauvage, de l’hybride entre l’animal et l’humain. Cette personnification hirsute, je l’ai déjà ébauchée plusieurs fois dans mon travail, car elle implique cette relation construite entre nature et culture et qu’elle renvoie à la figure de l’idiot que je trouve fortement liminaire. Lors d’une performance au musée d’histoire naturelle de Genève en 2015, j’avais déjà fabriqué une large tête surdimensionnée sans visage (masque), une tête en cheveux humains.”—Julie Monot, 2018

Context #2

It’s hard to trace the origins of a Green Room, a term defined in traditional Anglo-Saxon theatre as a dressing room for artists; a place to wait before entering the stage. If Teatro Real’s Salón Verde in Madrid is predominantly green, it’s not always the case with the modern versions of this waiting room, which often keep from the color only the name. In cinema, for example, the color green is often used as a background, by means of a screen used to easily merge two sources of video together in post-production. In the editing process, green—which differs the most from human skin—can easily be removed and replaced with a new background.

Theory #3

“But just as life on the earthly plane is always throwing down a bridge between the discordances of things, it also consists in every inside and every outside separated by the door. Through the door life moves from its being-in-itself in the world and from the world in its being-in-itself.”

Handy (2018), Julie Monot, GREEN ROOM © Julien Gremaud, Alpina Huus, Arsenic

Poetry

“What am I? Nosing here, turning leaves over

Following a faint stain on the air to the river’s edge

I enter water. Who am I to split

The glassy grain of water looking upward I see the bed

Of the river above me upside down very clear

What am I doing here in mid-air? Why do I find

this frog so interesting as I inspect its most secret

interior and make it my own? Do these weeds

know me and name me to each other have they

seen me before do I fit in their world? I seem

separate from the ground and not rooted but dropped

out of nothing casually I’ve no threads

fastening me to anything I can go anywhere

I seem to have been given the freedom

of this place what am I then? And picking

bits of bark off this rotten stump gives me

no pleasure and it’s no use so why do I do it

me and doing that have coincided very queerly

But what shall I be called am I the first

have I an owner what shape am I what

shape am I am I huge if I go

to the end on this way past these trees and past these trees

till I get tired that’s touching one wall of me

for the moment if I sit still how everything

stops to watch me I suppose I am the exact centre

but there’s all this what is it roots

roots roots roots and here’s the water

again very queer but I’ll go on looking”

—Ted Hughes, Wodwo–1967

Wodwo (2018), Julie Monot, GREEN ROOM © Julien Gremaud, Alpina Huus, Arsenic

Réflexions du sujet #0.1

“Pour Alpina Huus II, je serais tentée de poursuivre cette figure et lui fabriquer un corps/costume en cheveux. J’imagine ce personnage présent dans le lieu de manière continue, la question de la temporalité de la performance est assez importante pour moi, car elle sous-entend un rapport moins théâtral et qu’elle permet à la figure de s’inscrire dans le décor, mais aussi en tant que public afin de brouiller les pistes sur sa nature. Ce personnage mystérieux serait juste présent et en interaction avec les autres nombreuses propositions de cette exposition. D’un point de vue logistique, cette performance pourrait être réalisée par différents performeurs qui pourraient se glisser dans le costume en alternance. Je joins à ce mini texte une ébauche de la figure, quelques images de la performance au Musée d’Histoire Naturelle ainsi que quelques images de représentation d’homme sauvage qui m’inspire.”—Julie Monot, 2018

Proposition #2

In GREEN ROOM, her most ambitious project to date, transformation starts on the opening night, with a 4-hour performance during which each artwork is brought to life by performers, and by means of a sequence of lights and smoke effects. The artist has developed a light pattern that evolves from white fluorescent light, typical of a contemporary exhibition space, to a more dramatic, cinematic green over the course of a 20-minute cycle. As a result, the green light dramatically affects the perception of colors, visually transforming all the elements and characters of the exhibition. From a psychological perspective, it’s been observed that green light can enhance concentration and tends to create a state of alertness. On the other hand, an over exposure to white fluorescent light—the most common light source within corporate environments—can induce stress and paranoia.

Golden Boy (2018); Sculpture is Not Dead (2018), Julie Monot, GREEN ROOM © Julien Gremaud, Alpina Huus, Arsenic

Theory #4

“As for the different intonations that prevail in the impression they produce the bridge show how many reunifies the subdivision of merely natural being; the door, how man divides up the uniform and continuous unity of this being.”

Proposition #3

At the end of the 4-hour performance, everything is back into place, and yet each sculpture carries the invisible traces of its recent activation, giving its final form to the exhibition. After the opening night, the sculptures will then be activated again during the following week, this time without announcement, during the following week, creating unexpected overlaps with other programmed performances and the daily life of the art center. Forming a retrospective constellation, the 17 sculptures all emerge from Monot’s eclectic repertoire and biography, with quotes taken from modern art history, Pop music, classical literature, and fashion, to name only but a few. Not without humour, high and low cultures are merged together, contributing to a non-hierarchical vision of collective memory.

Theory #5

“Since man is the being that connects, that always has to separate and that cannot unite without separating—we must first get a spiritual hold on the merely indifferent being of the two banks in their separateness, in order to be able to go on and link them with a bridge. Likewise man is the limit-being, who has no limit. The determination of his being-at-home by means of the door means that he has separated a fragment from the uninterrupted unity of natural existence. But as formless delimitation becomes a Form, the limitedness of the latter finds its meaning and its value only in that which the movement of the door makes possible: in the possibility of soaring at any moment beyond this limit, into freedom.”