The Assange Condition

Cesare Pietroiusti interviews Miltos Manetas

From May 11th, Miltos Manetas’ exhibition “Condizione Assange – Quaranta ritratti di Miltos Manetas. Una mostra che apre per restare chiusa” will be installed at Palazzo delle Esposizioni in Rome, but will remain inaccessible to the audience. The public will be able to see the forty portraits only on the condition that Julian Assange will be freed.

Courtesy Maurizio Mancioli, São Paulo, BR

At a certain point, you decided to paint portraits of Julian Assange. One a day, or so. When did you start? Why Assange? Why oil paintings?

23 February 2020. Yanis Varoufakis and several comrades from Diem25 are in London. Along with Brian Eno, Roger Waters, Vivienne Westwood, Zižek and others, they are trying to draw media attention to the Assange case. It’s not easy; not many people are interested in the condition of a man who has spent the last 8 years “locked up”. However, only a few days later, Assange’s condition resembles the condition we will all find ourselves living in, something that we could never have imagined…

I feel lucky here in Colombia as I’m free to come and go to my studio in the Páramo whenever I feel like it, but I feel that I also have to do something for Assange. I’m reminded of Diogenes who, in the middle of a war, rolled his barrel through the streets, trying to contribute to the common cause of peace. I start to paint a portrait of Assange. Faces aren’t my strong point, and Assange has a rather difficult physiognomy, but the painting comes out well enough. Then I ask myself: what do I do with this painting? Sending it to my gallery for sale doesn’t seem “politically correct” to me. So I put it on Instagram and see if anyone wants to have it for free… and I immediately receive many requests! I give the portrait to the first person who asked for it, and make a second portrait right away. Same story: I discover that a lot of people want a portrait of Julian Assange. I do a quick search on the Internet. He was kidnapped on April 11, 2019, but his saga began eight years before that, when he was in self-imposed isolation in the Ecuadorian Embassy in London—as a precaution, more or less like us now. In Assange’s case, he was trying to escape the revenge of the U.S. government; but his long quarantine wasn’t enough to save him from that “virus”. Now he is in mortal danger, and international law—which could save him—is powerless: his detention is in fact illegal, as are his arrest and his possible extradition to the United States, where he risks the death penalty.

At first, perhaps, I plunged into this project in order to “help” Assange; now, with the current epidemic, the terms of the matter have changed. The fact remains that I’ve decided to paint a portrait of Assange for every day he spends in prison. And, of course, to give them all away to other people.

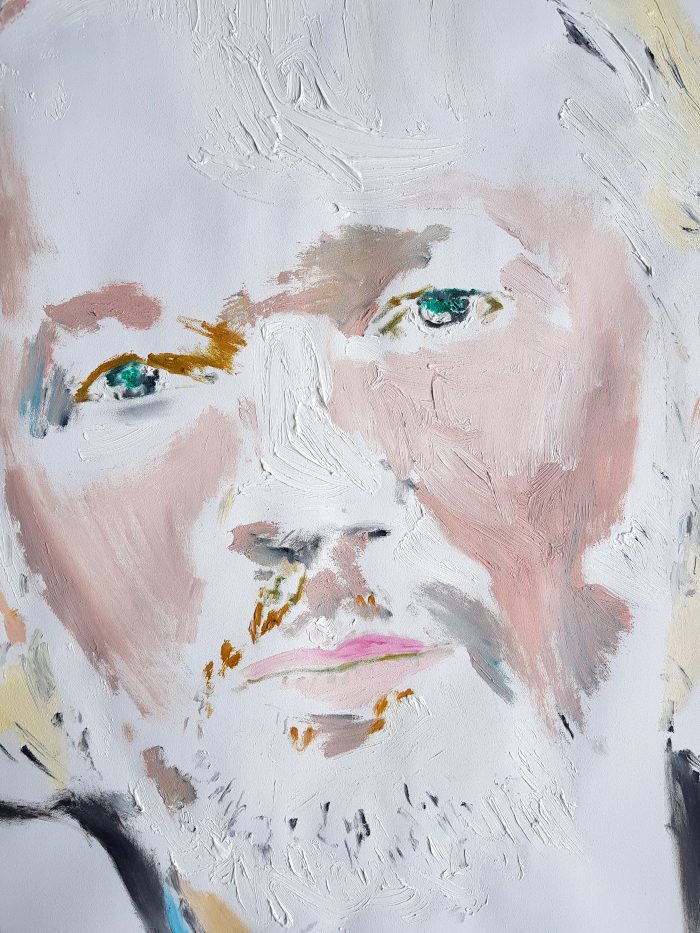

Courtesy Christos Tzovaras, Thessaloniki, GR

The portraits are published on your Instagram account and the first person who “likes” them becomes the owner of that day’s portrait. What’s behind this mechanism? Is it to offer support to someone who’s being persecuted? An experiment in the use of social media? A validation of giving as a critique of the art market?

The portrait does not go to the first person who “likes” it, but to the first person who states explicitly: “I want this painting”. If there is a gift involved, I am also the one receiving it because, if no one wanted the painting, the project wouldn’t exist, and I would probably have stopped painting Assange. Looking back at the reasons that led me to begin this project, I think that I was initially trying to establish some form of “relationship” with Assange. In a way, this relationship became apparent when I saw that so many people were excited to receive his portraits: somehow, I felt that he was becoming part of my “struggle” as an artist, and I was becoming part of his struggle, even though they are very different.

On the subject of social media, I would say that, ever since they have become part of our lives, they are my studio—everything I do passes through them. There was no desire to criticize the art market; rather, I felt the need, practical but also psychological, for someone to acquire these portraits immediately, just as soon as they were finished. Receiving money wasn’t important, nor was I interested in the buyer’s profile. I had to feel like I was giving them to someone. And that was how I came to the idea of the free offer.

The Assange Condition at Palazzo delle Esposizioni is an exhibition that is deliberately made to not be visited. It seems to me that some of the usual paradigms of the very concept of the exhibition, of the status of the public, and also of the function of the museum as institution, are overturned. This exhibition is made up of paintings that, though conceived to be immediately donated to others, still remain your works. As an artist, how do you feel about offering them up for an operation that appears to be based on renunciation, sacrifice, impossibility? Or should we consider your portraits of Assange not as veritable works in themselves, but as pretexts to talk about something else?

For me, the reason why these works cannot be seen in real life is not because the museum is closed, but because Assange has been living, for years now, in the condition of someone who has been kidnapped: you cannot see him in person—even though you can see countless photos and videos of him. In fact, we’ve decided that if by any chance his case is resolved while the exhibition is in progress, we will open “The Assange Condition” to the public as soon as possible—whether it be for a month, a day, an hour, it doesn’t matter! This “resolution” could happen: they want him dead and have left him in a prison rife with COVID-19. On the other hand, it is also possible that international law will eventually be upheld and Assange will be released—let’s hope so! No, the works are real paintings for me and not pretexts to talk about something else. Ultimately, for me the exhibition is NOT closed to the public: the show is taking place in an important institution, which like all institutions today—like all of us too, perhaps—is split between its physical existence and its media existence. This is why the publicity outside the museum is so important—to “prove” that the exhibition is indeed taking place, even if it can be seen exclusively in photographs and films, on the internet and in reports. As an artist, then, I do not feel I am making a sacrifice; on the contrary, I am grateful for the regulations against the epidemic that have led the museum to close, so the concept of the exhibition becomes even more intriguing.

Courtesy Lizzie Calligas, Athens, GR

Many people find that considering Assange a victim, or passing him off as one, is a simplification of a very complex reality. His controversial figure provokes ambivalent considerations and feelings. Is this perhaps also “The Assange Condition”? The difficulty to distinguish, clearly and once and for all, good from evil, right from wrong?

Of course, Assange is not Jesus Christ: no one ever accused Jesus of crimes against other people. Like Christ, though, and more than any other famous person, Assange “toiled” for his cross, and then made it as heavy as possible, and impossible to put down. What drives a creative spirit to do this? Why get into so much trouble? That’s the question I ask myself every time I begin a portrait. So far, the answer I’ve come up with is that Assange—somehow like Christ—received information and decided to pass it onto others, instead of keeping silent. It’s funny, they both got into the business of Revelation… Painting is also a kind of revelation. When you paint, things or “data” appear and you feel you’ve been entrusted to bring them to light. You could stop but you don’t, and then you have to face the consequences.

It seems to me that this condition also highlights the paradox of (until recently, at least) such large-scale media exposure, together with the impossibility—carefully enforced, especially by the British and Americans—of self-expression and communication, of sharing motives with others. Everyone is talking about you, but no one allows you to speak. You are bombarded by the media, while having no platform in public discourse. Perhaps, something of the “Assange Condition” is shared by many people, even beyond the Covid-19 quarantine. What do you think?

The #AssangePower project is entirely my own work, whereas this exhibition The Assange Condition is a collective project.

The show is a collaboration between me and all the people involved—from Assange himself, to judge Vanessa Baraitser who is holding him, kidnapped, to the photographer who took the photo I use to paint Assange’s portrait, to the collector who acquires the painting, to you, the team at Palazzo delle Esposizioni, to the courier who will take the works from Colombia to Rome, and to all the people who will share images of the exhibition on social media.

It’s a group self-portrait, about those of us who are locked up and trying to look into the future, as well as all those very many people who don’t have the luxury of a home to lock themselves up in and who can’t see beyond the immediate, cruel present.

Rome and Bogota, 30 April 2020. Translated by Sean Mark.

Cesare Pietroiusti: Let’s begin with the facts. The opening was scheduled for May 11th. By that date, because of the inevitable delays in postal shipping in these times of global crisis, your forty portraits had not yet arrived. After consulting with you, we decided to open the show anyway and mount prints of the works that we received by email. Once the opening has happened (and has been communicated), the exhibition officially “exists.”

So, to recap, The Assange Condition is an exhibition that was conceived to not be visited; however, as you said in our previous interview, “it is NOT closed”. Moreover, it’s an exhibition that exists even without the works it was supposed to host—it exists and, for example, it is talked about. Here, and elsewhere.

Don’t you think that these facts sketch out a process in which the work is the result of a collaboration between different people and circumstances, and of which you, the artist and the paintings—the actual works on display—are only a part?

I understand that every set-up of an exhibition requires a certain choice of colours, lights, backgrounds, etc. But it seems to me that there’s something more going on here. I think I can identify, in this space, the presence of a sense of expectation, which is perhaps different from the plain and simple preparation of an exhibition venue. Besides, as we said, the exhibition exists, and this colouring, for which you provided the instructions—this new state of the location—is part of the exhibition. Don’t you think?

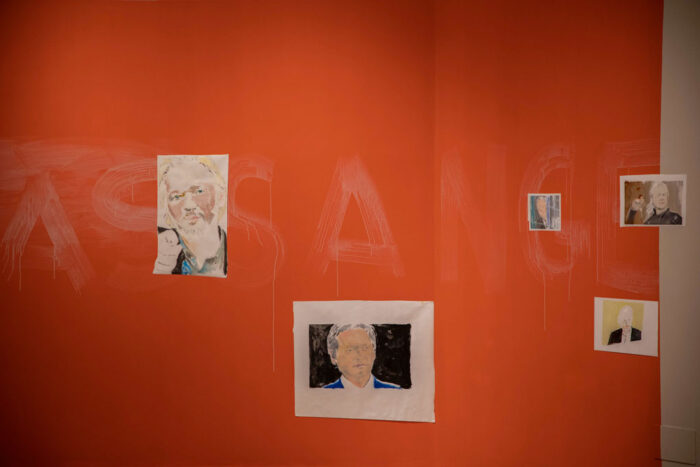

Miltos Manetas: The work I do on Assange, I call it #AssangePower. Even more than “power”, the right word would be “strength”. I feel that making these paintings gives me strength, giving them away to other people gives me strength, and now sharing them through The Assange Condition exhibition gives me even more! “Exhibition” for me means presence and, in this case, the presence of visual energy, generated by these paintings in a particular space—the Sala Fontana of Palazzo delle Esposizioni—and at a particular time in history in which we find ourselves in a condition similar to the one Julian Assange found himself in for years before his arrest, on April 11, 2019: self-isolation.

This presence, as I understand it, begins with the aura of expectation: the feeling we have when waiting for something that is about to happen. The process of setting up an exhibition is not normally shown to the public: the doors open and the visitor comes into contact with the energy of the work; this can be a shock, but the feeling of expectation is no longer there. But, in our case, we were lucky! The paintings’ postal journey was hindered—just as the arrival in Rome of Julian Assange would have been hindered, or my own arrival from Bogota.

This gave us time to rethink the environment of “The Assange Condition”. The Sala Fontana is a hexagonal room with a fountain in the centre, from which water no longer flows. Intuitively, to me, the room already seemed almost ready to “receive” Assange.

In recent months, I visited two online exhibitions in the Sala Fontana. One was “Nature in Every Sense”, an attempt to create “a large collective garden” with colourful walls, as bright as you’d imagine nature shines outside the Palazzo, or even outside Rome. The other was an exhibition-workshop from 2016 called “One-Way Systems”, with Braille panels on the walls that children (both visually impaired and not) had to touch in order to “see”. These were representations of the world outside of a room, at the centre of which—like an evocation—stands an inactive fountain. We find ourselves, today, in a situation in which our children communicate with their friends and their teachers exclusively through the unsettling touch of cursors and screens; for me, these two exhibition-workshops become particularly meaningful because they touch on the physicality and the real emergency that is hidden under the Covid-19 crisis: the climate emergency, which is the elephant in the room of all our discourses. The message of those two exhibitions—just like the colours of these walls—recall “Greta [Thunberg]’s complaints”. Julian Assange’s story also says something about the way we are forbidden not so much to talk about the emergency, but to uncover abuses large and small, the manipulations and mystifications that lurk behind the dominant discourse, including “green” conversations about supposedly “ecological” changes in production. Those who attempt to do so will be silenced. Not by some sort of “bad guy”—I don’t believe in conspiracy theories. Instead, I see a kind of “obfuscation” of the Law and democracy, a fatal coming together of bureaucracy and the media, which creates the conditions to silence each one of us, in the widespread apathy of everyone else.

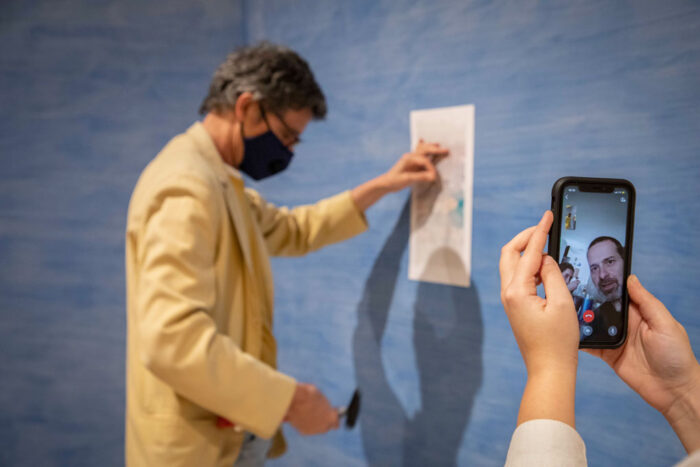

That’s why I decided to apply a coat of plaster over the colours that remained from the “Nature in Every Sense” exhibition. Painting plaster is practically dust. Last week, when we applied the first coat of plaster (I was supervising remotely, on my smartphone), it produced a kind of “Giotto effect”, which I didn’t have it in me to remove. I knew it wasn’t right for the space, but I was too happy with it to change it. A bit like the privileges we enjoy.

On the day of the opening—which we did on Instagram (chosen out of all the social media precisely because it was ill-suited to this kind of event)—I realised clearly that, if I did not “spoil” this beauty, the encounter between the Sala Fontana and my paintings would not take place. Now the space is just sombre enough, and unpredictable things can happen…

I’d like to ask you this question once again: what is the status of these portraits? Paintings that are made by an artist in Colombia and distributed free of charge, that may or may not be on display, and that are now, too, in a state of suspension between border crossings, post offices and whatever else. It seems to me that, even beyond their content and their reference to Assange, these objects are taking on very interesting and perhaps disquieting traits.

I am someone who is typically sceptical about the spiritual dimension: I’m persuaded only by the data and what I can see on the surface. But I also try to pay a lot of attention to intentions, consequences and connections. From my travels in the Amazon, and my encounters with communities—those we stupidly call “Indians”—I have found that there exists the possibility of an entirely materialistic shamanism. That even we, confused and lost people—“little brothers”, as they call us, with tenderness and tolerance—can invent with our computers and our networks.

Painting, especially when it is done with oil on canvas, remains for me the most powerful computer that Western civilization has produced. This is because—in contrast to the other arts—with painting everything is revealed immediately, at the very first instant. One glance at a canvas by Raphael is all it takes, and your life is no longer the same. But what painting cannot do is bring people together. In fact, it easily becomes a screen: it separates and hides those who look at it. It’s perhaps also for this reason that wretched people often become great lovers of paintings… Nowadays, however, the existence of the “network” has transformed everything. Paintings, with their materiality and through their reflection in the network, can become tools for a new materialistic shamanism.

It comes to mind that these paintings are a kind of physical prosthesis of yours (because you can’t travel and come here), or the expansion of one of your thoughts which, however, in this multiplication of states and suspended places, becomes more scattered and difficult to define. Can I say this? It seems to follow the model of contagion…

It’s exactly like a form of contagion. This is also why I refuse to be thanked by the collectors of my portraits of Assange for the “gift” I give them. It is not a gift: the fact that they receive these works puts in motion a (contagious) ritual that would otherwise be impossible.

I hope that, in the long term, my project will contribute to the configuration of a world where it is no longer possible to imprison someone like Assange.

I agree. When the work becomes a part of a collection, separated from the artist and the world, it is put in a sort of prison. With the spotlights on it, in dust-free rooms, but without the freedom to say what it hasn’t said so far, and without the possibility of becoming something else.

Rome and Bogota, 15 May 2020. Translated by Sean Mark.

Cesare Pietroiusti: The portraits of Assange have finally arrived, and are now displayed all together here in the “Sala Fontana” of Palazzo delle Esposizioni. The Assange Condition has thus taken another step forward. Let me give you my impression of this particular moment. The fact that the exhibition is hermetically closed to the public, and the story behind the whole operation, are not the only things that make this installation unusual compared to a “normal” exhibition of oil paintings; being here, you sense that there is a “presence”, perhaps not of a physical person but of a personality, more than the presence of paintings. In short, it’s a little bit as if Assange were here, rather than his portraits.

Miltos Manetas: Exactly! I also feel this presence and—you’re right—it’s not the presence of a person, at least not of a human person. I believe that, for the time being, the Sala Fontana of the Palazzo delle Esposizioni is home to Assange’s media presence: a version of Julian Assange’s media persona. It is also possible, however, that another presence can be felt—that of the creator of this exhibition! The Assange Condition is undoubtedly a collective process, which started with my paintings, with Clara Tosi’s invitation, and with your participation, and which has come to involve all the friends at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni, who, in one way or another, have made this operation possible and knowable. But I think that the “Maestro” here, the Great Coordinator, is none other than an… Artificial Intelligence! My idea of AI is quite different from the one you might read about in the pages of newspapers. For me, AI is a conglomerate of information: data and possibilities of data, which are collected—as if by a process of attraction—around a being (human, but also animal or plant). It is an instantaneous and changeable network that creates… the “moment”, which gives the semblance of reality in a way that is similar to the simulation produced by videogame software. While this is happening, AI also creates something that exists, in the sense that we can sense it—the kind of presence you were talking about. His presence.

You talk about a system that includes many people and situations, organisations and circumstances—including us, the Post Office, Customs, all sorts of regulations and connections. Now, I really like this idea that the exhibition is actually a system that is produced gradually during this time—a bit like how this dialogue between us develops week after week. This system is a complex one, which we set up only partly on purpose, and which is based on desire. There are people who tell me that every day they wait for the moment when you post a new painting on Instagram, and perhaps, here too, there is a certain desire to see beyond the panels that block the exhibition from view. In this sense, what’s happening now at Palazzo delle Esposizioni is not only a gesture of closing something off, because the closure itself, the invisibility of the exhibition, are part of a system of relationships that, inevitably, continues to expand.

I believe Julian Assange is the inventor of this paradoxical invisibility you speak of. Before taking refuge in the Ecuadorian embassy, he was photographed like a star—his expression was captured from every point of view possible. Like all of us, Assange was moving around the planet all the time, until he stopped—for an 8-year “quarantine”—in that embassy. There is something significant, I think, in the encounter between the complex “computational cloud” that Assange had become and a given place. Such an encounter presupposes the computational importance of that specific place: this might sound like a spiritual fantasy but, in the end, it is a belief that all of us visual artists share. In London, Assange became a “brushstroke” upon the city, upon the part of the Western world that I call the “Total North”. That brushstroke of freedom is able to hinder certain processes of “development”, and that’s why Julian Assange has become public enemy number one to speculators, to those who would like the South to disappear and the whole planet Earth to become a site of Production.

Condizione Assange. Quaranta ritratti di Miltos Manetas. Courtesy Palazzo delle Esposizioni, Rome and the artist.

It seems to me that your concept of “Artificial Intelligence” is very similar to the Marxian concept of General Intellect. Marx perceives that one of the effects of the Industrial Revolution, that runs parallel to the development of class conflict and the hoped-for liberation of the proletariat, is the possibility of a new society in which labour becomes a compound of manual human activity and the effects of the intelligence that produces machines, which in turn are able to produce other labour force. In this complex system many different elements (human and machine, for example) are connected and work together.

GI instead of AI! What a nice concept, I didn’t know it! And what a beautiful expression, General Intellect! Well, another aspect of my work as a painter is to introduce new terms like the Neen [a movement invented by Manetas in 2000, Ed.] or, sometimes, to re-introduce forgotten terms like General Intellect which I will now begin to use, or “tired” terms like Post-Internet. I’m convinced that we must improvise some “do-it-yourself” theories around terms like these, to redeem our intelligence from the slavery of industrialised culture. To use GI against AI, for example: General Intellect challenging Artificial Intelligence…

Rome and Bogotà, 3 June 2020. Translated by Sean Mark.