Conversation Over Conservation

An interview with Adelita Husni-Bey

From September 12 to 14, as part of Hidden Histories programming, the workshop The Collection in Turmoil by Italian-Libyan artist Adelita Husni-Bey was held, curated by Sara Alberani and Marta Federici with Valerio del Baglivo (LOCALES) and co-produced with the Museo delle Civiltà as part of the European project Taking Care – Ethnographic and World Cultures Museums as Spaces of Care. The workshop is intended as an investigation of the museum institution and a moment of collective learning.

Giulia Crispiani: La collezione in tumulto is a workshop which carries on with what LOCALES and Hidden Histories have already been activating within the Museo delle Civiltà, specifically regarding the collection of the ex Colonial Museum—as part of a broader project to review the institution’s spaces, archives, and collection. Your workshop in particular is meant to reflect upon central issues such as nomenclature, ownership and provenance. Who took part in the workshop? How is this meant to interact with the general process of institutional revision?

Adelita Husni-Bey: The museum, as you point out, is currently reviewing the way it operates, and the workshop was an attempt to graft onto this process by suggesting thinking about the decolonial through a transfeminist lens. LOCALES and I invited participation gearing toward specific embodied knowledges (meaning knowledge derived from experience), that could speak to states of transition (including gender) and research in the field of decoloniality. About 30% of the participants applied to an open call and, crucially, the group also included the museum’s staff. Participants had different relationships with the museum’s collection; some knew it intimately, like the museum’s own researchers and curators; others were learning about it for the first time. These are some of the words I noted from our introductions, which occurred after a series of silent movement exercises, and offer insight into the wide variety of our backgrounds and interests: botany, inter-species, education, “patrimony,” transfeminism and sci-fi, video-making, publishing.

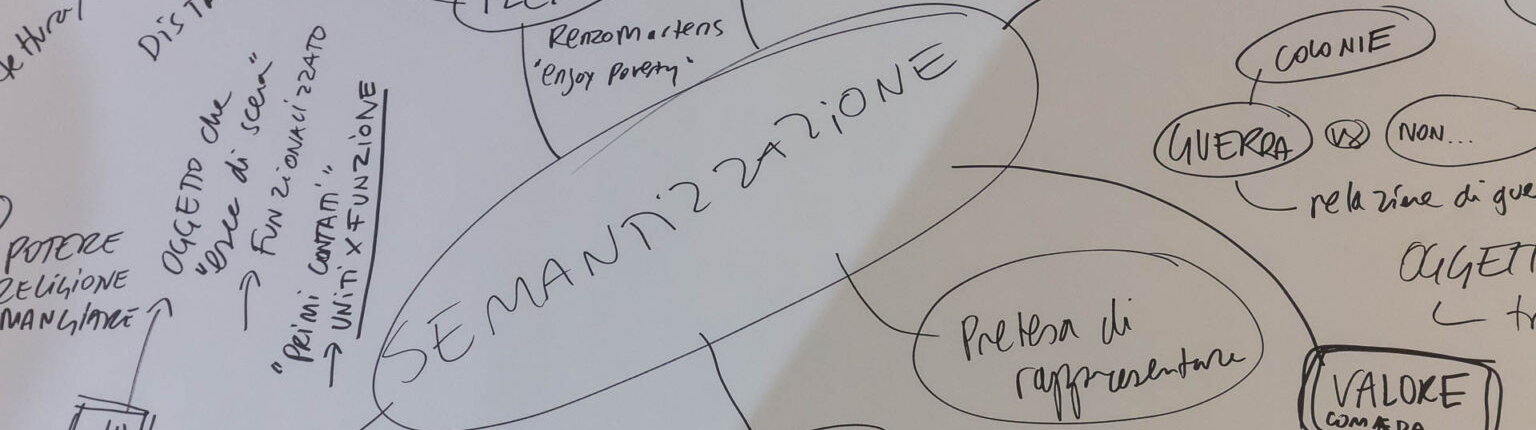

In the long term, I hope that workshops, like the one I led this fall, will become an integral part of the museum’s decision-making processes—I envision this as establishing a “permanent laboratory” within the museum. This permanent workshop integration, which must always include their staff, would help the museum understand itself and interrogate the logic that comes with showing, communicating, and therefore sorting (in the sense of spatializing rather than fixing) Italy’s colonial past. On the first day of the workshop, I read a quote from Fanon’s seminal work The Wretched of the Earth to the group “If we examine closely this system of compartments, we will at least be able to reveal the lines of force it implies. This approach to the colonial world, its ordering and its geographical layout will allow us to mark out the lines on which a decolonized society will be reorganized.” In a sense, the workshop is an attempt at understanding the organization of colonial storytelling, through objects and their indexes, in order to derail it. Naming and nomenclature have an intimate relationship with organizing, inherently taxonomizing, and ascribing forms of value in ongoing attempts at racial-economic domination, so the question of how objects are described, by whom and for whom in the present can be an undoing of that legacy and contributes to the ongoing structuring of a society’s value-systems.

What kind of (intersectional) methodology was applied during the workshop? What was its result?

In practice, the workshop relied heavily on political theater as its operative tool, as it has the ability to go beyond the meaning-making that can be achieved through discussion alone. For example, with Image Theater—a type of theater developed by Augusto Boal as part of the arsenal of the Theater of the Oppressed—the group began the workshop by investigating power relations through their bodies, in silence. In fact, this was the very first activity we participated in, before any kind of verbal introduction, including sharing our names. From our embodied reflections on power, we began to make connections between power and museology, power and colonialism, on a large scroll of paper which accompanied our process throughout. Some of the reflections noted on our scroll were: “power can lead to impotent liberation,” “power’s dialectic between solidarity and oppression,” “pushing and caressing are enclosed in the same gesture.” We also visited the museum’s anthropological galleries (open to the public), and noticed the effect of some decisions made by the museum on our perception. Some of our reflections: “the museum is a grave, the museum has no sound,” “the museum doesn’t allow us to touch or forces us to touch improperly,” “how is access, in its varied meanings, present in the museum?”

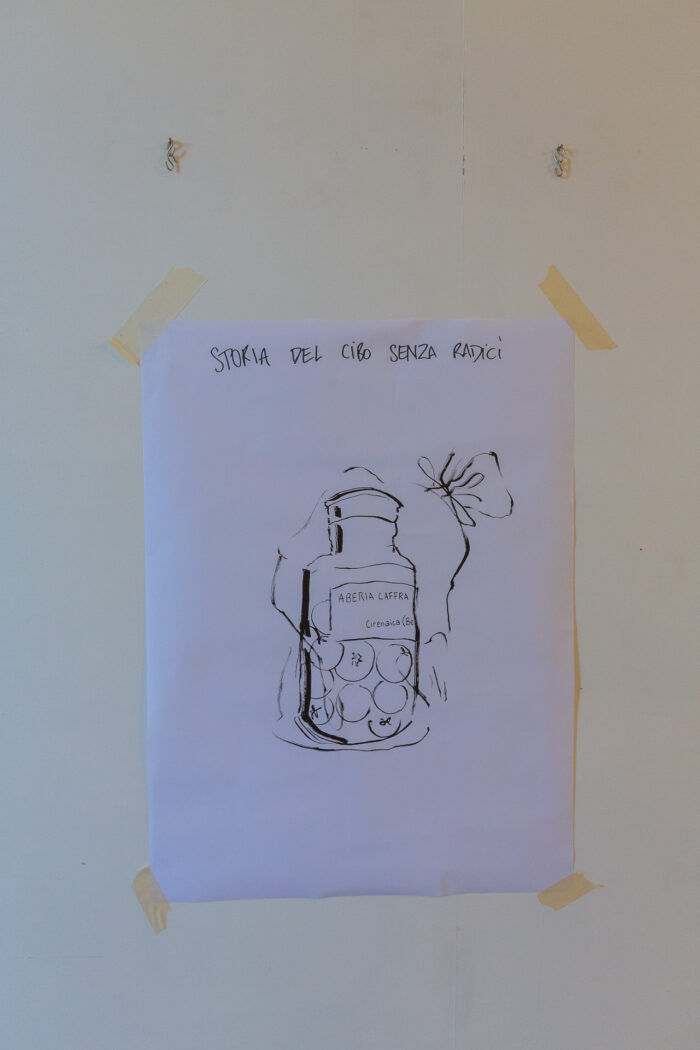

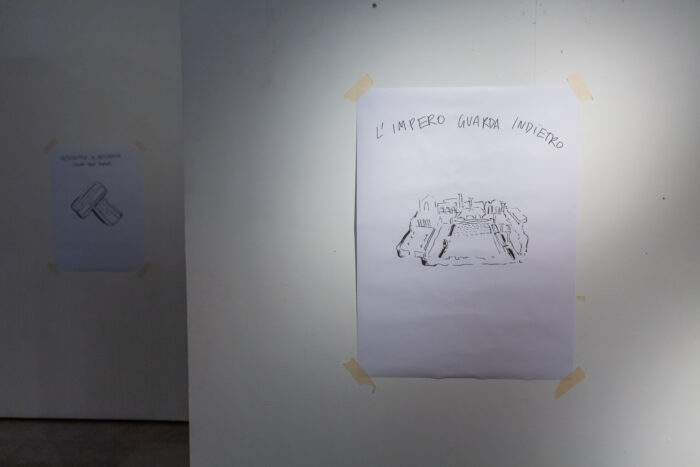

The workshop involved visiting and choosing objects from the collection’s deposits as “guides,” critically reflecting on how the objects “spoke,” and experimenting with descriptive language and drawing, producing possible counter-taxonomies. In the depot, we found out that objects were originally accompanied by a very simple index, poorly detailing the object’s appearance and provenance, and that researchers used it to reconstruct the object’s history, often with great difficulty. Seeing the index on the object so lacking, offered us insight into the particular kind of alienation objects suffer from when they are removed from their cultural context and used for imperialist propaganda. Some sections of the collection clearly represent the circulation of goods and the Italian government’s attempts to invite trade, highlighting the crucial role of capital flow in colonial enterprises. One such object was a jar filled with fruit. I quickly realized they were fruits I knew from my childhood spent in Benghazi, Libya, where part of my family comes from. I drew the jar, thinking of a new index title for it: “a history of food without roots.”

The tangible result, so far, is a set of advisory guidelines, in the form of a diagram, that suggests (sometimes practically) strategies the museum could adopt and questions it should ask itself when curating programs and rethinking its procedures. For example the guidelines controversially ask the museum to prefer conversation over conservation—even if this risks damaging objects, and to try to move the objects from the depot to public spaces through ad hoc programming, perhaps as an open-air museum. The guidelines challenge the museum’s ordinary role as a space of sacred preservation and invite a fluid relationship between the museum and its objects.

To institute, define, and establish a “permanent laboratory” practice, and to use labels (exploring the use of other media rather than text) that answer 5 questions: who stole this object? Who remembers this object? Who made this object? Who used this object? Who exhibits this object? I believe the result is also intangible, a shift in consciousness resulting from the experience that we all had through the workshop and will inevitably carry with us.

Throughout this process you are meant to envision a museum where the collections are in a “state of (perpetual) change and in constant transition.” How did you come up with this idea and what does it entail? What would be the implication for identity politics and History? What kind of affect and effect will it have on its “future” audience?

Relying on Paul Preciado’s statement that we “live in transfeminist times“—meaning that we are part of the ongoing dismantling of binary identities (“boy-girl, hetero-homo, animal-human”) and that dis-identification is an important feature of our condition—the workshop sought to think about decoloniality through a transfeminist lens. If fixity is an illusion and transition the reality of lived experience, can the museum respond by setting in motion an ongoing process that entails an open and public revision of its procedures? A museum beyond binaries? Can it accept a “workshopping” of its procedures for naming and describing objects? Can the decisions made have an intentionally temporary quality? This seemed to me a necessary foundation in the context of a collection, and thus a museum, trying to establish itself against the backdrop of its past self-narration. At this juncture, when the museum is attempting to dis-identify itself from its previous functions, my contribution is intended to encourage its structure to remain open, not to ossify itself but to accept processuality as a guiding principle. For example, in the guidelines that resulted from the workshop—which are supposed to be a guiding ethos for decision-making processes—we suggested that whenever the guidelines are reworked, working groups should be created within the museum, which must include staff, paid invitees (who are not “experts”) and open public participation.

The Museo delle Civiltà is already abandoning many of the classic tenants of an ethnographic museum: a single authoritative voice, an assumed neutrality, ways of “othering” and burying the origins of its collection. The workshop sought to accompany these ongoing processes and develop models, reflections and tools that could respond to, critique and assist them. I am not sure what this will imply for the future—3 days is hardly an introduction—but if the museum continues to be responsive to this idea, it would mean being able to partake, through workshops, in the museum’s “undoing.” It would also mean that the material from these experiences would be available to the public and that LOCALES, the artist, the museum and the participants will continue to explore how to implement and divulge the guidelines.

What is the pedagogical potential of (a very much urgent) revision—renaming to re-classify both artifacts and keepsakes?

Re-signifying is a necessarily semantic process: the name of the thing suggests its place, its perceived origin, how it got somewhere and how to “place it” (and how it places itself) in the world. As Gaia Delpino, a researcher and Museo delle Civiltà staff member suggests in her text “Oltre Montanelli,” reflecting on the public contestation of the confederate statues that followed the George Floyd riots, museums, like statues, have a socio-political function and therefore can be contested. The derailment, revision, and contestation of meaning revive readings that have been obscured by dominant narratives and therefore act on a society’s sense of collective belonging. I am thinking of the ideological underpinnings of this attempt to demystify and reveal forms of colonial violence (which are also inherently imperialist, racist, capital-driven and linked to “patrimonial” ideals) in the context of Fratelli d’Italia’s recent electoral victory, and how a museum like the Museo delle Civiltà, could become a bastion of cultural resistance in the face of an avowedly nationalist, heteropatriarchal governing party with roots in fascist movements. A museum the size of Museo delle Civiltà, which holds numerous other anthropological collections, in addition to the approximately 12,000 objects from the ex colonial collection, constantly faces political pressures from which it must tenaciously defend its programs. The pedagogical function of the museum’s current direction, which has its roots in LOCALES and Hidden Histories’ programs, could serve a political imaginary necessarily at odds with a homogenizing culture that celebrates “Italian-ness,” and this seems particularly important to me at this historical juncture.

Where do we (collectively) find our words to detect and name oppressive narrations first, and how do we shift them back to undo (and repair) what’s unjust?

This question made me think of something a participant said during the workshop: “The object’s narrative survives beyond the powers that contend it.” On a practical note, studying together, reading out loud to each other, establishing practices that include collaboration to decode contemporary powers that “contend an object’s narrative” are fruitful ways to identify “oppressive narratives.” I think we will also find words in recognizing materialist,ecofeminist, decolonial, and abolitionist writing as true, prognostic, and relevant.* Regarding undoing and repairing, I want to move away from justice’s appeal to the institutional/correctional, because although I work within the institution, I remain skeptical of the ability of any institution to deeply engage with and support radical ways of working with “justice” more broadly as a retributive framework. A liberal paradigm of justice implies that it is indeed possible to ‘right a wrong’, obfuscating the way these objects returning home cannot and should not erase decades of massacres and pillaging. Similarly, I don’t believe in paradigms that use shame and guilt as the primary means of appealing to morality, because they are incapable of building lasting forms of solidarity; I do believe that rigorous forms of integrated, collective, long-term experimental research (with materialist analysis and embodiment at their core) have this potential and should continue to be practiced inside and outside the institution. I don’t want a liberal idea of fairness, I want the working class to be empowered through organization. I want the extent of colonization to be recognized in the present. I want institutions to be open, to fund critical research and to exhibit work that advances our capacity for collective critique and international solidarity.

*Some of the writings that have been important to me include: CLR James, Sylvia Wynter, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Angela Davis, M. Nourbese Philip, Jackie Wang, Denise Ferreira Da Silva, Cedric Robinson and Frantz Fanon