Spring 1399-2020

A letter from a quarantined Tehran to a quarantined Rome

Tehran, 24 March 2020

Dear Giulia,

Sun is setting on my 30th day of quarantine. From my balcony I can see a bit of sky, which today is bright blue, and few playful clouds in it. I’m lucky—many Tehranis can’t see the sky from their apartments, but for sure everyone can hear the same silence. Since June 2009, when 3 millions of us walked in the silent march in Tehran, I always imagined our strongest unity to exist in silence. When a crowded noisy city like Tehran decides to go silent, there are a million words behind. When I write the word silence, a poem by German female poet Margot Bickel (born in 1956 in Germany but maybe better-known in Iran than in Germany) immediately comes to my mind:

“Silence is full of the unspoken,

of deeds not performed,

of confessions to secret love,

and of wonders not expressed.

Our truth is hidden in our silence,

Yours and mine.”

When I was five years old, I remember my mum was trying to keep us in the basement of our house in Isfahan—that was the time of the bomb. I remember the alarm on tv, we used to call the red alarm. It was a continuous really loud noise, it could appear in the middle of tv programs and we knew we had to run to the basement, until the green alarm would appear again on the tv and radio. For a five years old child, born two months after the beginning of war, the red alarm was nothing extraordinary, it was part of daily life. My dad used to read poetry in the basement, with the radio playing in the background. My mum was entertaining us by repeating the poems until we could enunciate them by heart. I have a vague memory of Silence by Margot Bickel being one of those poems—although I may be mixing times and memories, as far as thirty days of quarantine allow for any plausible understanding of time. Anyway, the poem was also translated by Ahmad Shamlou, that is why Bickel is really important for Iranians. Today, I was writing a line of one of Shamlou’s poems on an old bed sheet for one of my neighbor to hang on their window:

“Mountains are together and alone,

Like us together lonely humans”

Three days ago—quarantine day 27th—was Nowruz, the Iranian new year. Each year, the New year in Iran comes at a specific time of the day, in the exact moment when the sun completes its circle. This year it was precisely at 7:19:37 am. Nowruz (which literally means new day) is always about this exact moment, and it’s really somber for Iranians not to be able to celebrate it together. This year the whole concept of time got confused in our minds.

“Open the knot, My heart says, With the coming spring, The thunder will cry, It will rain, The plains will rise.” Poem by Parvaneh Forouhar, handwriting by Nazanin Shivayi. Tehran, Spring 1399.

When I was writing Ahmad Shamlou’s poem with the brush, I was trying to remember calligraphy lessons in primary schools. Quarantine is about remembering. When the image of the future collapses, the now becomes free and the past, which never finished, allows you to get back to your life. I think about the word “future”. A pause comes to my mind: here in my city, the future never became a consensual project between the people and the state. It’s been 41 years we are trying to find an image for the future the revolutionaries created in their mind, while they were pausing everything else by conquering the streets and squares of Iran. Perhaps their imagination for the future is beautiful, utopian, and with the greatness and generosity of a revolution, it includes everyone. A generosity that, in reality, didn’t last long. Since then, many images for a future entered the battle to become a national project, a direction, a plan. None of them ever succeeded and the suspension of not having a clear image for the future became our present today. Maybe that is why Covid19 is not stealing any future, it’s a new arrival in a long old battle.

Although as usual I see endless power in the hands of the military and security forces, and in the hands of those who want to control our lives to the max, but on the other hand the nature of the virus, as a soft, fast and bloody creature that treats us all equally and even confounds military forces and their plans for control. This confusion is where we can meet again.

I’ve spent the past week painting banners for my neighbors to hang from their windows. I write the poems they choose, most of which are about spring and Nowruz. For Persian speakers, classic poetry plays a special role during Nowruz. Following the turn of the year, people who gather open a famous poetry book from a poet called Hafez and randomly read a poem out loud. They believe that the poem symbolically reveals what will be happening in the new year—some kind of divination by poetry. As though, treasuring the philosophy of life, the Hafez book of poems is there for people to randomly open and get a reading for the year to come. So, I have invited people to choose a poem and send it, for me to make them a banner to hang from their windows. Throughout almost all the poems that friends and neighbors sent me, I could read a mix of sorrow intertwined with the beauty of spring.

Yesterday I was writing a poem written by Malek o-Sho’arā Bahar. He was a poet, politician and journalist during the Constitutional Revolution of Iran. “Bahar” is his pseudonym, which in Farsi means spring. He has many poems starting with bahar, and he uses this word metaphorically both about himself and about spring. Yesterday I was writing a sentence from him, saying:

“What a waste, The day is new

And you,

Wistful

And sick at heart”

I thought about the time that politicians were poets, and poetry and politics were embedded strongly. They were one thing, an imagination of something that doesn’t exist—imagination of an impossible. Although their romanticism seems relevant in our time, their politics still exists in their poetry, as strong as their imagination against the illusion of reality. Did this time really exist? Or is it just my dream for the future?

I had to wonder where poems come from, while I was making another banner that read:

“Yet my patience

Rivals

The tall stature of desire”

Poems come from the intensity of the experience, moments in which meaning fills each word. Even wasted words become alive, because their meaning happens, and senses can touch it before their abstract version appears as a word. At this moment meaning is strongly present in the smallest action we do in our houses—every single move, every thought which passes my mind, in silence. This silence brings about ambiguity as well—a kind of fog between my bedroom and the kitchen—my eyes try to go beyond and see hundreds of friends sitting around the empty table in the living room. In silence, I can hear their loud laughter. Poems too, come from ambiguity. From a time you can’t see details but can imagine them, as much as distances, scales—and the shape of the unseen, like the light of twilight when the sun is either setting or rising. That precise moment in which everything has an equal light, those moments on hold—pauses.

Tehran, Spring 1399.

Me and you saw many sunsets together, mostly around “your sea”. That very sea you feel the smell of from far—you call it “my country”. The sea that once upon a time connected Latins to Arabi, a road through the minarets, porches and arches, from one city to another, one could see from the deck of the ships when approaching, before that sea became a bloody border between Europe and Africa. Maybe this image never existed either. The Mediterranean sea as a road of connection from one city to another is just an imagination in my mind on the 30th day of quarantine, while I’m losing my understanding of borders, while the virus moves fast around the world. We saw the sunset in Beirut together, in the timelessness of twilight. I imagine the silence in Beirut these days, and I wonder how can people stay at home, only a few months after conquering the squares? I remember the last time I left Beirut, early morning in the corniche, waiting for a taxi to take me to the airport, the sky was bright pink and fishermen were as sedentary as usual, staring at the sea horizon, right before the young revolutionaries woke up and came to claim the streets. It was the 17th day after October 17th. I imagine a post-corona Beirut like that early morning. We also looked at the sun while it was setting in Cairo, from Moqatam’s hill. In Cairo it seems like the sun sets everyday forever. Every sunset we saw there was the 1001th sunset. Do you imagine Cairo as silent these days? How loud and strong can be the silence in a roaring city full of loud words. The ones on the streets of Tehran and Cairo, these days, are showing us how an informal economy with thousands of laborers with no guarantee for any form of future is holding our cities in their hands, to prevent them from fully collapsing. I try to imagine Fajr Azan in Cairo in the days of isolation. One thousandths of a second of delay between each mosque. In the pause we live in, my body floats between these continuous cities I have found myself in, now with the help of twilight of the thirty day of quarantine I lose the notion of distance, of scale, and I feel an invisible thread passing through my body and reaching over the empty streets of the cities in between, reaching you in Rome.

Tehran is silent these days, I can hear the sound of birds in the center of Tehran from my apartment, while I’m writing these poems on these old bedsheets. Sometimes I try to listen to the silence. I hear the sound of a car far on the highway, or a neighbor fighting a few blocks away, or the sound of forks and spoons from the kitchens, with the heavy smell of food coming from the backyard. We are in a pause. I try to imagine the faces of people in their apartments, their bodies, their hands, after being washed many times in the last thirty days.

Today I received a message from a friend in the US. Normally I see her life on Instagram, a beautiful perfect life with colorful flowers in the garden and a dog she takes out everyday. She asked me for how long coronavirus stays on the clothes. I went to check the folder I made on my desktop, because everyday when Covid19 arrives in a new city, a friend of mine asks me a similar question. I even categorized the questions. I have even a category for confronting different forms of ignorance. A category for saving people from conspiracy theories. A category for those who knew everything even before Covid19 arrived in our world, and for the anxiety and panic of information. For the first time in my life, I feel I have a folder of other people’s future questions.

Living in the delay of a catastrophe is like staring at things immersed in the twilight. It gives me the possibility to confuse former categories. It smashes the word “progress” and brings in a new intense meaning to each letter of it. The pause, the protest of silence, the delay that happened to the unbreakable linear time of progress, gives me the voice to read Bertolt Brecht again:

“Truly I live in dark times!

A sincere word is folly. A smooth forehead

Indicates insensitivity. If you’re laughing,

You haven’t heard

The bad news yet.”

I’m writing to you and I know my words will land in a city where sorrow sings in the background of all of those “happy” musical balconies. I know there is no delay between Iran and Italy anymore. People under these two nation states’ identities used to always be heavily analized by the “more progressive” countries through parameters of efficiency, thousands of words wasted for showing how corrupt are the states in these countries, as if they ever manage to rule all the thousands of self organized communities, here and there. But finally, Covid19 arrives as well in the studios of those tv programs in “the North” and whatever their analyzers tried to rationalize about those statistics apparently went wrong. Waves of various propaganda flowed from their channels to justify their position as observers. But no tv host can observe Covid19, when even they should be confined at home, living what they were trying to analyze just a few weeks before.

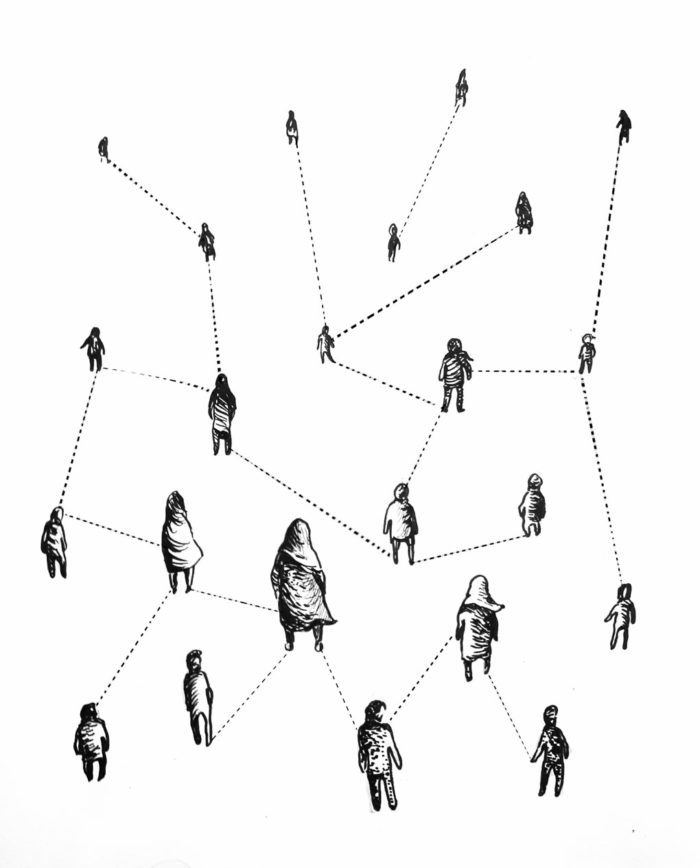

Between you and me—there is no longer any delay between the cities we live in. Now we know that those who are buried without their families are not just numbers. Those who mourned keeping distance from the graves and from each other, were lonely human beings of our time (Spring 1399-2020) surrounded by the open arms of the catastrophe. From there we start to create a living meaning for the word solidarity… for each letter of this word. From there we allow ourselves to imagine another reality. An imagination the world will receive with delay, from the first line of the catastrophe.

Dear Giulia, I’m writing to you with no delay. Light is gone, sun completely set, it is time for Scheherazade to continue her stories, in the night’s seduction she entertains the power to save the life of thousands of others from the king’s cruelty. In the after sunset darkness, I look at the photo of a funeral where family members had to stand 150cm from each other. They are praying, I guess, in silence, and my eyes try to see thousands of people keeping the same distance, all of those who could not mourn for their loved ones, and never touched the soil that accepted the bodies of their loved one. Let’s look at this image together, with no delay, in silence, with an unceasing effort to see all the bodies in between these 150cm.

I miss you,

Golrokh

Illustration by Golrokh Nafisi.

Rome, 29 March 2020

Dear Golrokh,

I’m writing on my 8th day of isolation. When I returned from Tunisia, I had to register myself at the ASL (Italian health system) and on the website of the region where I reside. Right after the experience at the airport, where cops were shouting at us to keep the safety distance, in an interminable queue formed by masked women and men, wanting to return home as they were asked to. The guard at the border checked my passport and my self-signed paper where I declared that all I wanted was to go home. He held the paper on the window of the checkpoint and instructed me to photograph it—and I assumed he was going to keep it. I felt something that I rarely feel. The sudden awareness of my role as a citizen. My passport became big and heavy in my pocket, so much so that after the final checkpoint, I immediately put it back in my backpack.

As instructed, I called as soon as I arrived. Any object I touched, I felt as if I would infect it. I’ve felt the virus—in a sudden awareness in being a vector of touch and a carrier of breath. The invisible virus could have caught me and I would be able to transmit it onto any surface. I threw my clothes on the ground and made the phone call almost naked, sitting in the sun. Again, I’ve found myself queueing—and I had to think about all the many times I have avoided queues, either by renouncing or by changing my choice, or by standing up at the very last minute before the gate would close. I saw my privilege. Anyway, I was the 8th in line and I listened to the registered music and voice reassuring me that someone would have picked up at a certain point. I remained sitting on a stool, not daring to touch my bed nor my chair, thinking about a whole world going through this procedure. I imagined everyone being at home, and I pictured all the sofas I have ever seen in my life, and I imagined everyone sitting on it and looking outside their window. I almost didn’t dare to open my window and go on my balcony, in solidarity. I thought about distance and absence.

When finally my turn arrived—sorry I don’t know if I am calling the right number, I’ve just returned from abroad and I’ve been told to register myself for isolation—I got very conscious of the words I was uttering—a kind female voice on the other side asked me my data, again, and filled it in, instructed me to take my temperature twice a day and call back in case of symptoms, as she listed them once again and asked whether I had someone who could take care of the groceries—I do, I said. In the first 24 hours of my quarantine, I measured my temperature 4 times. The first night a hypochondria I have never met before in my life got my temperature up to 36,9°C, one step before fever, and a pleasant nervous dry cough. No other symptom. I thought about high school, when I used to try (always unsuccessfully) to cause myself a cold to skip school and training. I would open the window during winter nights and breath through my throat. Today, I am sure everyone is missing badly going to school. My more constant thought so far has been: how long is two weeks? If I can’t see the end of something I never ask myself how long will it last. But I do wonder how long until I will see my family, kins and comrades again? I am not afraid of inactivity—again privilege—but I do fear the absence of touch. These days I’ve found myself missing the traffic jam, the cracks on Rome’s asphalt and all the wild grass that blooms in between the bricks on buildings and sidewalks. Every singular detail of it, which usually becomes the spine for my longing and writing. I visualize all the details that I will notice and enjoy when I will finally leave my house again. I imagine the meeting with each and everyone of my friends, in the post-pandemic world. As for revolution, and war, and earthquakes, and love stories, and natural disasters there is always a before and after.

As soon as I quickly adjusted to my seclusive daily routine—imagining to be confined in a cloistered convent—all I began to desire was silence. Before feeling home, I had to prepare my household for the quarantine. The news told me that this could have gone on forever. For everyone I knew I calculated what day of quarantine they were in, and witnessed a sense of delay. Most of my friends and acquaintances had already spent two weeks inside. I counted the hours since the last time I was freely walking outside. I thought about shaving and getting tattooed. I made plans for house renovations, and filed a shopping list. I counted the hours, until I’d be able to touch another body. Meanwhile, I thought, I’ll spend my time writing. Again I thought about everyone’s writing—and silence.

The world united in a common destiny, going nowhere. No planes are flying above the sky. In the night, the city breathes and shimmers, silent. Only cops, cleaners and thieves are legitimately on the streets. Every night I try to remember what we did when we could be out at night. And I envision the first night we will be out again, the reopening of the corner bar. I foresee a carnival. Many say, these days, that there won’t be a way back. We can’t possibly ever go back. Even my family members became aware of being part of history. I wanted to tell them—you always were, you make it daily—but I desisted. So, Covid stands against progress. At least against its capitalist side. It holds our timeline into suspension. Our space shrinks and our time dilates, we zoom into details. We can’t go anywhere. I don’t even remember if what I am writing now are somebody else’s words I’ve been reading these days. I don’t need to put an alarm, I wake up with the light, like a farmer on the field, the sky is all I can look at. I allow myself the pleasure to miss Tehran, now the furthest ever, or the same city. We cannot go further than 300 meters from our homes, what difference does it make? For once we all live in the same city. Our screens speak the same language. To know how to psychologically bear the quarantine and stop the contagion we share tips, with a few weeks delay from China to Iran, to Italy, to Spain, to the US. New jokes become old in a day. All busy with prophecies of the aftermath, theories run behind the day. I don’t want to give prescriptions, I just want to make sure to keep my body trained to return among others.

Rome stands silent, beside the music coming out of the buildings. Rooftops and windows became essential. We’re all smoking looking outside, while similar thoughts run through our minds, with the slightest delay. At times, we temporarily accept this condition as perpetual. If we can’t estimate how long it will last, then rather not even think about it. I let the city embrace me, in her past and future possibilities. This collective fragmented presence, so close yet so far. Finally the city continues, despite they closed all the borders and stopped talking about it. The pandemic hit the fan, and spread accordingly to its current. Everyone became busy with remembering past calamities, comparing different times. How did we cope? For once we look at ourselves as one species, a dangerous one. As if the planet asked us to stop. The biblical catastrophes of 2020, a story older than any divinity. The most cynical among us appreciate this historical moment, eager to see beyond it—no matter how long it will last, we’re going to thrive and tell the story, and this episode would become the event that made us move forward, even if forward meant to look back. All I ask myself is when they will allow us to see each other again. Although in my head, at this moment, we’re all neighbors. All we see online these days is empty cities and houses’ interiors.

I’ve sent you the gloomy pictures of the pope preaching alone to an empty Piazza San Pietro. You could hear the sound of the rain and the seagulls screaming across the sky. He was asking his god to save us. Rome’s sky was dark and weirdly blue. The whiteness of his robe looked even brighter. He limped back toward the cross in silence, while a baroque choir was singing. I will never forget this image. I am prepared for the disaster to come.

I hold you dear in my present, in absence.

Giulia