Ruins of Perception

Reimaging nightlife beyond Eurocentric templates and logic of hedonism at Berlin Atonal 2025

(6 AM). Exhausted. Perhaps, just ecstatic. The only certainty is that stopping the movement is inconceivable. Electric shocks run through your bones, making them dance on the relentless tempo of the BPM. Your hips sway, hypnotized. They push against the surrounding air, fueling an electrified agitation that propels you forwards. Keeping your eyes open is an option, but smoke fills the space to the point that the only bodies your gaze can reach are those closest to yours. You then tune into the rhythm of a stranger whose movement is typical of ravers. Shaved head, bare chest. Yours is a restless dance as if this were your last night ever. The night before the end. Behind the Tresor’s bars, Rrose drops a new track. Subwoofers vomit dark, deep, dynamic and dizzying sounds, all at once. It’s a march of disturbing basses, an invisible army of thunder. Your sweat glands release unstoppable droplets: your heart rate rises; shivers cover your skin. Your face changes in the induced darkness, as dawn begins to breathe outside. Suddenly, your anxiety displaces carefreeness, dissolving the party illusion into Berlin’s decay. Before you realize it, the room has become a site of projection: a suspended time where abandonment, seduction, and desire meet loss, trauma, and anger. Yet, on the verge of collapse, you can’t stop dancing.

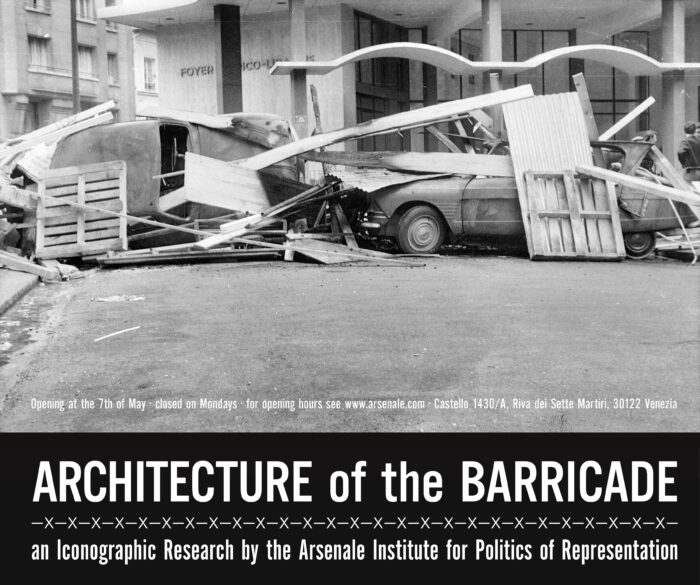

At Kraftwerk, the former power plant of Berlin Mitte, the 12th edition of Berlin Atonal unfolds as a five-day programme of music, performance, and curatorial experimentations. One of the elements composing this year’s Atonal’s constellation is Third Surface, an exhibition project curated by Adriano Rosselli. The central hall on the ground floor features an assemblage of tables flanking the stage: a spatial configuration that invites the audience to sit, linger, and experience each performance within an atmosphere that folds different temporalities into one shared present. An aesthetic and physical environment which draws inspiration from the Kabarett that flourished in Berlin during the Weimar Republic (1918–1933), a time of unparalleled turmoil, suspended between the economic instability that followed World War I and the ideological radicalization that paved the way for fascism.

With the establishment of the Weimar Republic, most forms of censorship ended, and kabarett enjoyed a time of unmitigated freedom, lasciviousness, and lewdness. As Laureau notes, they functioned both as a means of escape on one hand, and perhaps more importantly, as a means of coming to grips with the strange new environment, and the lingering trauma of war. Operating at the edges of legality and decorum, these spaces reflected the emotional state of the society, embracing irony, excess, and fragmentation not merely as symptoms of decline, but as imaginative responses to historical crisis. Within these venues, social disintegration was turned into a performative language that embodied the aesthetic of decadence, and staged collapse as a site of invention and desire. In doing so, they served, albeit indirectly, as spaces of resistance to state control, refuges for dissidents where music and political provocation turned into tools to dispel fear and challenge the political violence and discontent with democratic institutions rising across Germany.

This notion of decadence as a form of resistance resonates powerfully with Berlin’s post-Wall club culture, which similarly transformed the city’s voids and ruins into spaces of collective experimentation. In the 1990s, abandoned factories and power plants became temporary sanctuaries for bodies, sounds, and identities in flux — places where freedom was rehearsed through excess, and where the nocturnal life was still infused with utopian promise. Over time, however, that very aesthetic of decay and subversive culture was gradually absorbed into the city’s global image: Berlin’s underground became a brand, its darkness a commodity consumed by tourism and real-estate speculation.

It is precisely within this dialectic between resistance and assimilation, authenticity and spectacle that 3rd surface intervenes. By reactivating sites once charged with the energies of subcultural experimentation, Berlin Atonal does not merely stage performances but orchestrates a reflection on the city’s own cycles of erosion and renewal. Its installations and sonic architectures transform former industrial sites into arenas of perception, where historical residues and contemporary sound practices converge. In this sense, it reclaims decadence not as a nostalgic gesture, but as a curatorial strategy: a means of re-engaging the city’s fractured temporalities and reimagining what nightlife might still mean today. Within this expanded environment, multiple narratives, ideas, and aesthetics unfold and wave together into a fabric of political stances, affective experiences and fragmented memories. Three works part of this ecosystem trace a path to navigate different regimes of visibility and to reclaim disgregation to reframe the present starting from its ruins: Nelson Makengo’s nocturnal portrait of Kinshasa, which redefines darkness as a site of resistance, Billy Bultheel’s allegorical fugue through collapse and historical amnesia, and Tanja Al Kayyali’s textile cartographies of loss and endurance. Three works that articulate new paradigms of appearance, retrieving subversive forms of collective presence.

A Short History of Decay, Billy Bultheel

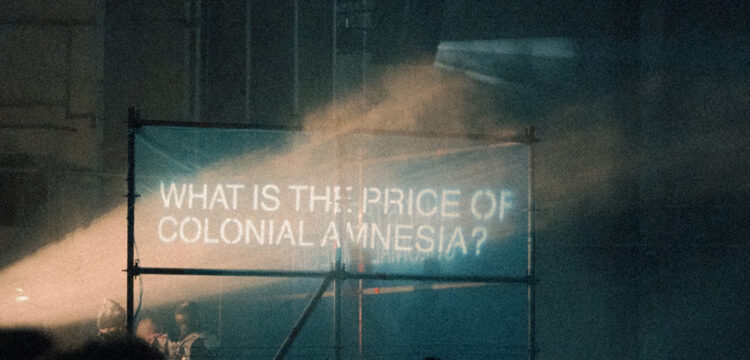

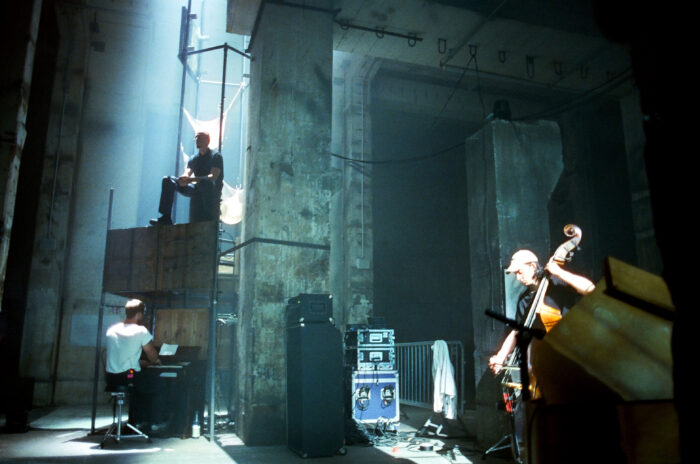

The industrial and monumental metal structures of the central hall of Kraftwerk render a sense of suspension and openness in which performers and audience engage in a dimension of closeness and proximity. This liminal space is the stage for Billy Bultheel’s The Fugue State, the second iteration of A Short History of Decay, an ongoing performance project structured around three monologues which express different positions towards the German context in the aftermath of October 7th: 1) defiance and rebellion, 2) passiveness and complacency, 3) dissociation. Focusing on the last position, The Fugue State develops as a performance-installation that operates at the intersection of Baroque-inspired composition, sculptural intervention, and site-specific spatial activation. The performance moves forward Billy Bultheel’s exploration of historical collapse as both a political and social condition, intertwining E. M. Cioran’s aphoristic reflections with texts by Etel Adnan, Walter Benjamin, and Henri Michaux.

The narrative revolves around the personification of Benjamin’s Angel of History, who is trapped in a “fugue state,” struggling to comprehend in which historical fragment she has found herself. The angel gradually reconstructs meaning from scattered historical debris and reorients herself guided by the sound of a harpsichord, a flute, a harmonium, and a bass, which, often haunted by electronic interludes, distortions, and spectral granulations, trace new paths through a devastated landscape. The sound spatialization across the various speakers accompanies the listening experience toward imaginaries that are simultaneously apocalyptic, devotional, and sublime, stirring sensations of profound melancholy, restless tension, and fragile rapture. It is an acoustic environment that draws the listeners into a state of suspended contemplation, oscillating between transcendence and unease. The work’s ritualistic atmosphere does not offer solace, but rather exposes the fragility of the historical present characterized by repression and structural violence. In evoking the “aftermath of October 7th,” Billy Bultheel’s composition transforms the devotional into a site of confrontation: the harmony of sound collides with the dissonance of history, compelling listeners to reckon with the moral and emotional ruins of the present. What initially appears as divine contemplation thus becomes an act of witnessing, a moment in which listening turns into ethical awareness.

Rising Up at Night, Nelson Makengo

Ground floor. A room opens to the right. It’s the Projektionsfläche dedicated to the screening program co-curated with Felice Moramarco. Here, 3rd surface unfolds through moving images by presenting a series of experimental films that explore how sound and image can construct narratives alternative to the Western regimes of visibility. In a global climate marked by renewed forms of extractivism and Eurocentric narratives, these works imagine other ways of appearing.

Among them is Rising Up at Night by Nelson Makengo, a film that offers a complex portrait of Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo and the artist’s birthplace, capturing the city’s vitality, contradictions, and collective strength. Set predominantly at night, the film questions the very possibility of vision in a context where light, the emblem of progress and hope, remains precarious. In recent years, many cities across the Congo River have been hit by severe floods that crippled power systems, leaving them oscillating between illumination and shadow, appearance and disappearance. Yet, improvised light sources—flower-shaped flashlights, sparking glasses, portable lamps—punctuate the night, transforming scarcity into a choreography of resilience.

The sonic landscape plays here a central role. Generators hum and prayers overlap with laughter, while distant radios merge with the buzz of insects and electricity. The act of listening becomes the primary mode of perception, and in the acoustic space, sound becomes a means to affirm life and presence within the darkness of the veiled image.

Yet to remain in darkness is not just an infrastructural issue here, but a metaphorical condition for people whose visibility is defined—and confined—by colonial optics. Reclaiming opacity in the Glissantian sense, Makengo refuses the demand for transparency. Through a tapestry of nocturnal images, often too black or too ungraspable to be fully discerned, Rising Up at Night turns the dark into a site of resistance and self-determination. Visibility emerges from within: the community does not ask for light, they create their own sparks. Meeting, singing, and praying together, they reinvent the night as a space of affection, music, and creation, transforming invisibility itself into a collective act of self-determination.

The Moon, Tanja Al Kayyali

Going up the stairs of the power plant, into the side corridor overlooking the central hall, a metallic structure hovers midair, inhabiting the space with vibrant stillness. Light falls from above, accentuating its monumental scale. This is The Moon by Tanja Al Kayyali, a Palestinian artist born in the former Yugoslavia.

The work comprises five textiles woven into a metal grid that functions here as a frame, recalling the “security fences” first erected by Israel around Gaza in 1971—instruments of enclosure that turned the territory into an open-air prison. Yet Al Kayyali dismantles this logic: only five sections of the grid remain, as if the confining wall had been shattered or broken, exposing the possibility of passage. Boundaries no longer confine; they enable passage.

Each bar bears a distinct embroidery: The Moon, The Tree of Life, Stars, Graves, and Borders, realized through tatreez (تطريز), the traditional Palestinian embroidery technique recognized by UNESCO as part of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Originating in the Canaanite period,[1] tatreez has evolved into a coded language of survival, historically transmitted by women as a way of mapping belonging and lineage. Tanja Al Kayyali does not merely preserve this language; she reconfigures it. Each embroidery transforms a geographical wound into a cosmic metaphor. The Moon, linked to the lost village of Aqir, adopts the colors of the Palestinian flag, turning the celestial body into a symbol of luminous persistence. In Stars (Bethlehem), constellations form a cartography of longing, orienting the exiled gaze. Graves (Hebron) translates mourning into geometry, asserting that even absence has form. The Tree of Life rises vertically against the rigidity of the grid, embodying growth within constraint, while Borders completes the reversal: its threads weave through the metal mesh, transforming the fence into a network of relations.

The installation’s stillness is charged. The suspended textiles tremble with the movement of air, producing a faint resonance as if the act of stitching itself continued in the present. This subtle sonicity, born from the friction between fabric, metal, and space, turns the work into an instrument of memory, vibrating between silence and testimony, past and present, absence and presence.

Through this interplay of material, memory, and reverberation, Tanja Al Kayyali constructs an affective cartography of Palestine, making the absent and the erased present once again. Each stitch acts as a counter-archive, a symbol of what persists despite erasure. The Moon transforms the logic of enclosure into one of connection, reminding us that resistance can also take the form of tenderness, a fabric that holds, even as it unravels.

Across these works, the night becomes both a metaphor and a method—a space where disappearance gives way to reappearance, and where resistance manifests as persistence, intimacy, and attentiveness. Through performance, moving images, and textile interventions, the artists challenge imposed hierarchies and conventions, revealing what history has obscured or marginalized. 3rd Surface illuminates nightlife as a time-space for the unseen and the absent. Engaging with a present marked by political upheaval, escalating atomization, and mass suffering, Berlin Atonal enacts a reclaiming of visibility and collective agency, attuning to historical and contemporary decadence as a site for reflection, care, and affective camaraderie.

[1] The Canaanite period refers to the ancient era (c. 3000–1200 BCE) of the Levant, encompassing the ancestors of the Palestinian people. It marks the early development of settlement, culture, and artisanal traditions in the region, forming a historical foundation for Palestinian heritage.