Reframing Violence

Violent images are part of our lives

The following piece by Eva Leitolf and Giulia Cordin introduces the book Violent Images, the third volume in the Negotiating Images series, edited by Eva Leitolf and Giulia Cordin. The previous volumes are Shoot & Think (unibz) and Landscape with(out) Locus (NERO Editions).

Through the lens of various disciplines, Violent Images investigates the politics of visual violence and its potential to provoke, subvert, and transform social, political, and media discourses.

A scene of devastation: grey, grim, ruined. As if in a fairy tale, two children leave through a rock arch, emerging into a completely different world: colorful, joyful, sunny. Images flash by in rapid succession: a palm-lined beach, splendid skyscrapers, golden statues, a shower of money. A voice chants over a strong electronic beat: “No more tunnels, no more fear. Trump Gaza is finally here!”

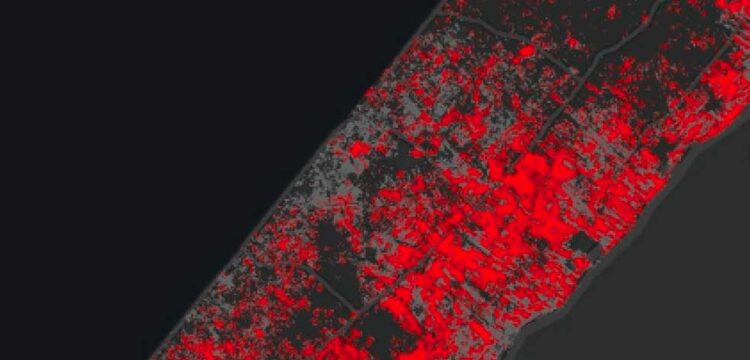

The US President posted this video on 25 February 2025, shortly after announcing his intention to turn the Gaza Strip into the “Riviera of the Middle East.” The footage apparently visualized his colonial plans for the warzone, which implied the death or displacement of 2.1 million Palestinians.

No source was indicated for the AI-generated video, raising question marks over the president’s intentions. Yet it was widely disseminated by international media outlets. Although it was broadly mocked, and generally treated with incredulity, the implications of its publication were rarely subjected to earnest critical analysis.

The Trump-Gaza video epitomizes the broader post-factual discourse that characterizes our political and media landscape today, demonstrating how hyper-aestheticization—understood here as a deliberate strategy of visual excess—functions as a strategic means of communication. Hyper-aestheticization both shapes and dulls our perception of events.

Myriad images confront our eyes every day: the horror of war, the suffering of migrants, the endless list of femicides. They flow past us continuously, mingled with other visual information in an uninterrupted stream of “floating images”. We live in a “chronic voyeuristic relation to the world,” as Susan Sontag wrote in the late 1970s, in which images of suffering and violence become objects of emotional and sensational consumption, drained of their power through spectacularization and mass circulation.

According to Sontag, this photographic praxis leads to a levelling and homogenization of meaning and generates apathy in the viewer. Images of violence may move, shock, or sicken us, but they can also make us numb to the suffering of others. They disarm us, leaving us passive and blind to the causes of the events. [1] Our responses mutate into a hypocritical, depoliticized form of liberal empathy. Suffering is processed in the instant, and we move on. No time or space to interpret, reflect, or respond to the conditions that produce it.

Mark Reinhardt takes it a step further, showing how the mainstream’s spectacularization of violence diverts attention away from the structural causes of conflict. Shocking and sensational presentations distract us from the unseen violence of the underlying structures, ultimately aestheticizing them. Visual representations of violence thus often reproduce the very logic of power they supposedly set out to disrupt. They create visual frames that perpetuate forms of structural violence and legitimize mechanisms of exclusion and subjugation. As Charles Heller and Lorenzo Pezzani put it: “[I]mages do not simply document the violence … but actively participate in it.” The image needs to be understood not merely as an object to be viewed, but as a proactive medium whose contextualization, circulation, and reception may stimulate or numb us, force us to look or look away. A medium that reveals and conceals.

The question of violence naturally touches on what is shown, but also how it is shown, by whom, and with what implications. While the visual content is certainly the most obvious aspect—images are violent if they show acts or consequences of violence—their “epistemic violence” must also be considered. Images are also violent if they undermine our ability to understand and navigate complex realities.

Immediacy, as the predominant cultural style of our times, seriously undermines our capacity for critical and collective thinking. Rejection of mediation encourages a culture of immediate gratification and superficial identification. The violence of the image must be sought and comprehended within the process by which the distance between viewer and image is negated. “Violence resides in the systematic violation of distance”—the distance that is crucial for critical reflection, the distance that enables us to think as well as feel. And that violence, Mondzain argues, is always political.

Counter-aesthetic strategies are crucial here, understood as practices that weaken or relativize hyper-aesthetic co-optation mechanisms. Artistic and aesthetic practices can serve as an antidote to the hyperaesthesia of digital sensory overload and to the aesthetic power of politics and the media, acting to restore the connection between perception and meaning.

As Reinhardt argues in this volume, the aesthetic can still offer space for resistance. Instead of denying—or “killing”—the aesthetic, it must be renegotiated. That means learning how to show and look more consciously and responsibly. If the gaze can be violent, it can also become a source of intimacy, recognition, and resistance.

The development of counter-narratives as critical praxis becomes an epistemologically radical counter-hegemonic act. It opens up spaces to challenge, understand, and interpret. It reestablishes the possibility for critical thinking, by restoring the distance between image and reality, visible and invisible, transparency and opacity.

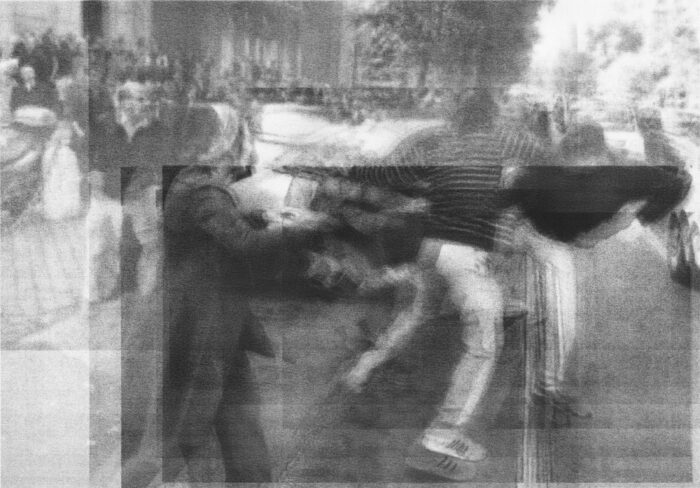

Images become political precisely where they resist immediate legibility and visibility, and thus avoid the risk of spectacularizing suffering and marginalization. Rejecting immediacy creates space for interpretation, forcing us to think harder, to look deeper, to reconstruct. In this understanding, images are more scenario than static representation. A performative dimension is activated, projecting the viewer into the image.

That is what we have sought to accomplish in this volume: to interrupt the stream of images and their passive consumption by employing elements that force the reader/viewer to consciously adopt a position when interpreting the material presented to them. The volume examines different forms of systemic violence, exploring counter-narratives and alternative scenarios that grant complexity and agency both to the marginalized subjects and to those who look with an eye to deeper understanding.

One means of so doing is collaborative production of visual representations that foreground the lived experience and testimony of those immediately affected. Nicholas Mirzoeff describes such moments as forms of “counterinsurgency,” where oppressed subjects assert their right to visibility and self-representation.

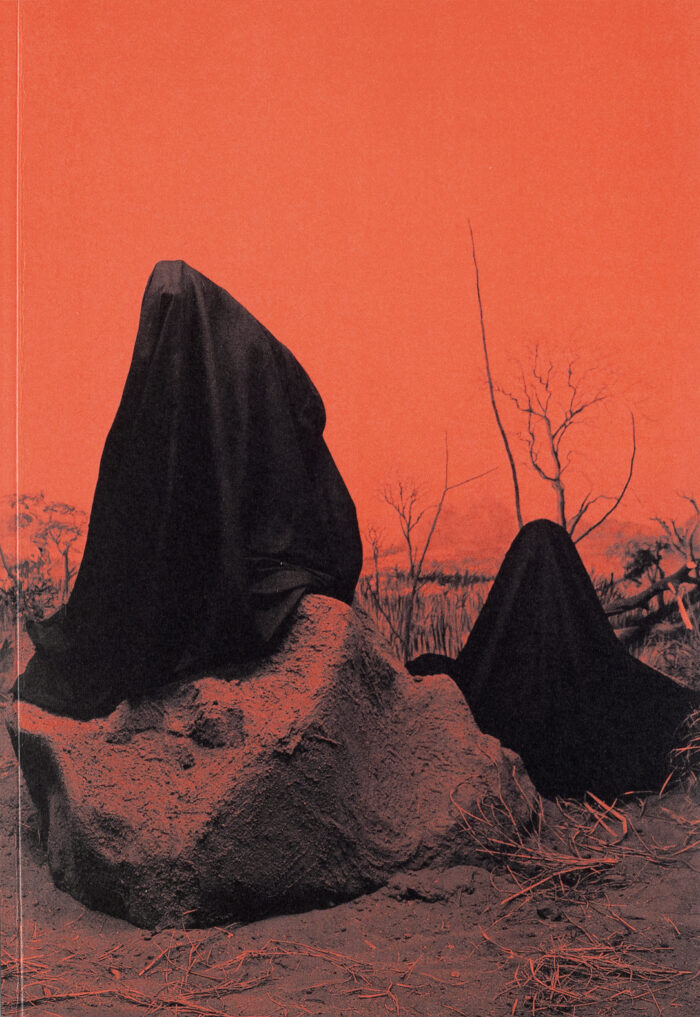

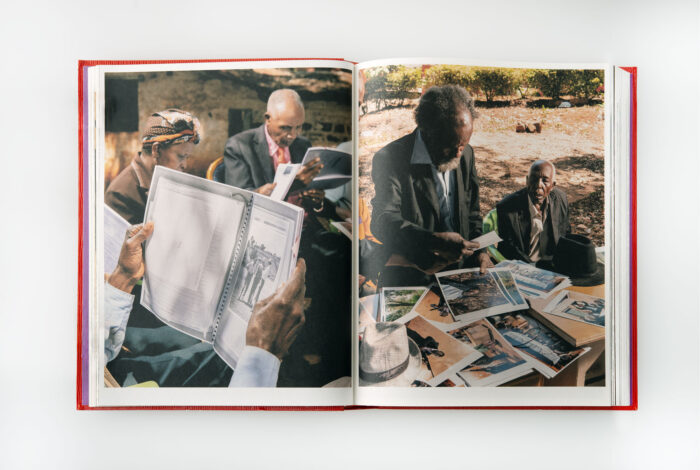

The images produced by the visual artist and researcher Max Pinckers are more than mere documentary artefacts. Instead they activate memory through performative processes and offer the participants a space where they can share their stories through acts and gestures that are rooted in oral and bodily traditions. This approach creates an alternative frame for challenging hegemonic historical narratives and fostering social and political change.

In a similar vein, the artist Monica Haller develops editorial platforms that enable war veterans to articulate their own experiences. Her concept offers her participants not only a means of personal expression, but a framework to reconstruct their personal memories and reassess the collective narrative of the conflict. By creating new possibilities for personal and public dialog, Haller promotes an artistic praxis that challenges and expands the roles of artist, collaborator, and audience.

In “The Apple and the Anthropocene,” Stephanie Polsky investigates the violence of images as the expression of a visual colonialism, in which aesthetic representations reproduce cultural, racial, and geographical hierarchies. The starting point of her analysis is her critique of the global imaginary, and of the aesthetic and epistemological rules that form our perception and interpretation of the world. By placing the concept of “whiteness” at the heart of her analysis, Polsky demonstrates that this violence is not only symbolic, but also has real effects on social power relations.

Lorenzo Gabrielli and Amarela Varela-Huerta explore the socio-economic conditions under which visual narratives about migration are produced and disseminated, in “The Border Spectacle during the Pandemic.” Their contribution investigates the tensions between journalism, business, and hegemonic narrative under the unusual conditions of the Covid-19 pandemic.

In their analysis of “Gender and Violence in News Media and Humanitarian Photography,” Roland Bleiker und Emma Hutchison dissect the gender-specific representation of power (and powerlessness). In reporting on war and crises, women tend to be shown as inert and passive, seldom as protagonists with agency and resistance. This reduction to the role of victim—and the associated aestheticization of female pain—contributes to a powerful form of structural violence that both presupposes and amplifies the inequalities. The visual linkage of masculinity with strength, honor, and the public sphere, and femininity with care, sacrifice, and domesticity, creates politicized security discourses in which “militarized masculinities” dominate the narratives and define international politics.

Elissa Mailänder’s “‘Who Likes Kidneys?’ ‘Fried in the Pan?’” investigates how violence is performed, represented, and shared within perpetrator groups. The example she scrutinizes is a video recorded by the “Scorpions,” a Serb paramilitary unit operating during the wars in former Yugoslavia in the 1990s. She focusses in particular on the visual construction of (para)military masculinity and the mechanisms of cohesion and mutual legitimization within the group. The video becomes a lens revealing the group’s acts of destruction and violence to be communicative practices replete with social and symbolic meaning, and rooted in dynamics of dominance and dehumanization.

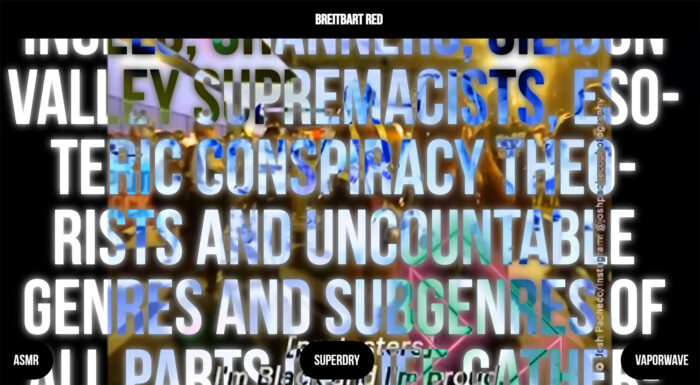

Finally, in “Fashwave,” Lisa Bogerts and Maik Fielitz discuss the visual aesthetic of the alt-right movement, taking the example of online visual language and its strategic instrumentalization for purposes of ideological radicalization. They analyze how digital visual language and meme culture are consciously employed to disseminate far-right ideologies, influence public discourses, and motivate radical acts. Their example, Fashwave, is a far-right adaptation of the Vaporwave style that combines fascist symbolism with futuristic elements and uses art-historical references to construct a trans-historical narrative that legitimizes far-right ideologies.

We believe that the materials assembled in this volume demonstrate the vital importance of the ability to read images critically, if we are to understand the complex and diverse dynamics of (structural) violence in our society today. It is not just about decoding the visible, but also questioning and challenging the ways in which images are constructed, contextualized, disseminated, and—in the process—politically instrumentalized.

Traditionally, in theory at least, democratic societies have handled disagreements by debating fact-based information. Today, techniques for manipulating perceptions, obscuring structural violence, and propagandizing power have become central elements of the political cultures of Western democracies.

Solo Avital and Ariel Vromen, who produced the Gaza video posted by Donald Trump, said that it was satire of course: “With humor, there is truth, you know, but it was not our intention to be a propaganda machine.” They were surprised that Trump had shared it without indicating who had made it, and had the impression that it had been taken out of its original context. They had not expected, they said, that Trump would post a video showing him “standing erected in the center of the city as a golden statue, like some sort of a dictator.”

The strategy of flooding the public sphere with contradictory images, statements, and decisions whose context and meaning often remain obscure, and at the same time stigmatizing critical media outlets as producers of “fake news,” destabilizes the foundations of fact-based public discourse. This deliberate communication strategy creates a vacuum in which the power of definition is ultimately surrendered to an authoritarian leader.

More than ever, the challenge of highly complex visual environments—whose levels of meaning are always in flux and increasingly shaped by potentially system-changing political actors—demands critical practical and theoretical approaches. Interpretive and mediating strategies are especially necessary to promote heterogeneous counter-narratives and reshape deeply embedded structures of representation and communication.

[1] See also Mieke Bal, “Hearing Voices, or How to Not Speak for the Other,” Lecture at the Voice, Migration, Narration seminar, Ateneum, Helsinki, Finland, March 12, 2008; Luc Boltanski, La souffrance à distance: Morale humanitaire, médias et politique (Paris: Éditions Métailié, 1993); Judith Butler, Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable? (New York: Verso, 2009); Lilie Chouliaraki, The Spectatorship of Suffering (New York: Sage, 2006).

Bibliography

Bal, Mieke. “Hearing Voices, or How to Not Speak for the Other.” Lecture at the Voice, Migration, Narration seminar, Ateneum, Helsinki, Finland, March 12, 2008.

Boltanski, Luc. La souffrance à distance: Morale humanitaire, médias et politique. Paris: Éditions Métailié, 1993.

Butler, Judith. Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable? New York: Verso, 2009.

Chouliaraki, Lilie. The Spectatorship of Suffering. New York: Sage, 2006.

Demos, T. J. The Migrant Image: The Art and Politics of Documentary during Global Crisis. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013.

Fontcuberta, Joan. La furia delle immagini. Turin: Einaudi, 2018.

Fuller, Matthew, and Eyal Weizman. Investigative Aesthetics: Conflicts and Commons in the Politics of Truth. New York: Verso, 2021.

Heller, Charles, and Lorenzo Pezzani. “‘All They Did Was Taking Pictures’: Photography and the Violence of Borders.” Philosophy of Photography 5, no. 2 (2014).

Holert, Tom. 2019. “Epistemic Violence and the Careful Photograph.” e-flux Journal, no. 96.

Kornbluh, Anna. Immediacy: Or, the Style of Too Late Capitalism. New York: Verso, 2024.

Mirzoeff, Nicholas. The Right to Look: A Counterhistory of Visuality. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011.

Mondzain, Marie-José. “Can Images Kill?” trans. Sally Shafto, Critical Inquiry 36, no 1 (2009).

Reinhardt, Mark, Holly Edwards, and Erina Duganne, eds. Beautiful Suffering: Photography and the Traffic in Pain. Williamstown, MA: Williams College Museum of Art and University of Chicago Press, 2007.

Sontag, Susan. On Photography. London: Penguin, 1978.

Sontag, Susan. Regarding the Pain of the Others. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2003.

Steyerl, Hito. The Wretched of the Screen. Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2013.

Weizman, Eyal. Forensic Architecture: Violence at the Threshold of Detectability. New York: Zone, 2017.Žižek, Slavoj. Violence: Six Sideways Reflections. London: Profile, 2007.

List of works

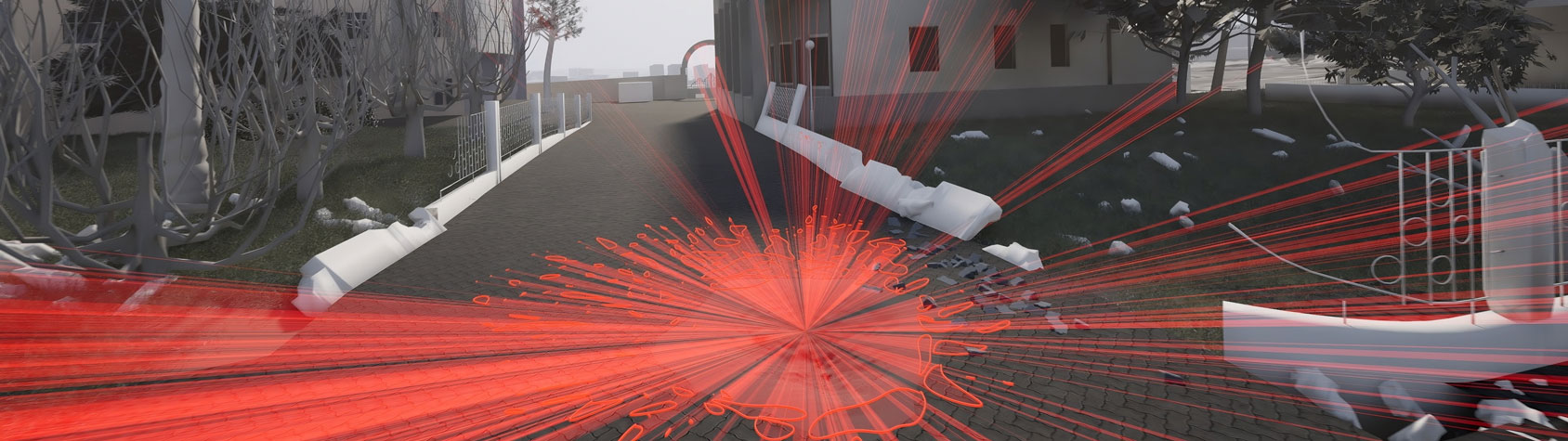

Forensic Architecture, “When It Stopped Being A War”: The Situated Testimony Of Dr Ghassan Abu-sittah

Ubermorgen, BREITBART RED

Max Pinckers, State of Emergency

Eva Leitolf, Postcards from Europe, since 2006

Susan Harbage Page, U.S.–Mexico Border Project

Sophia Rabbiosi, Exhibition: Violent Images – Broomberg & Chanarin, Eva Leitolf, Letizia Nicolini, Sophia Rabbiosi, Viola Silvi

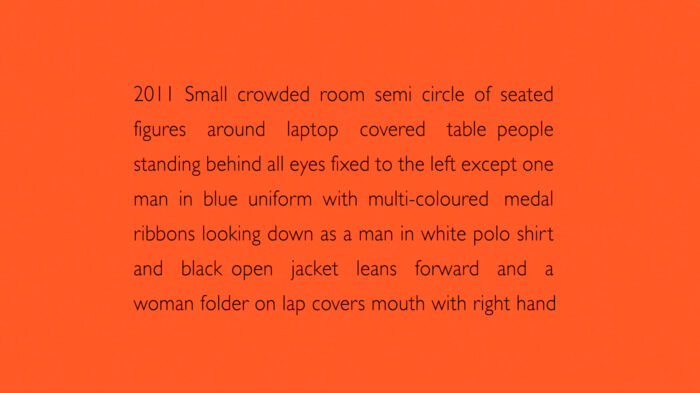

Edmund Clark, Orange Screen

Monika Haller, Riley and his story