Death by GPS

The worker is not, never will be a machine

Salvatore Vitale’s (Italy, 1986) solo show Death by GPS gathers videos, photographs, and installations which delve into issues such as labor exploitation, the gig-economy, and automated processes within the context of post-capitalism.

The project primarily focuses on South Africa, specifically in the Gauteng region. This location was chosen because historically it has been the center of imperialistic dynamics and labor exploitation due to its vast mining reserves. Today, Gauteng hosts many freelance workers in the IT field who operate for Western companies within the gig-economy system.

Salvatore Vitale analyzes how automation biases shape the relationships between individuals, labor and social structures that generate new forms of exploitation. The project explores the ongoing social and economic shifts influenced by technological developments and draws parallels with the historical exploitation of workers in the mining sector.

The following text accompanies the exhibition.

More people than one might comfortably imagine have driven cars off bridges and highways at the suggestion of their navigational systems. Far less interesting than the insinuation of some auto kamikaze conspiracy, this lack of driverly discernment—the displacement of one’s rational inner monologue with the hypnotizing dulcet tones of direction-giving voice actors—reveals a far more troubling sublimation of man and machine. In his genre-expansive consideration of the hybridization of humans and their technological tools, speculative documentary photographer Salvatore Vitale considers the fraught transhumanism of automated labor. The title of his latest project, Death by GPS (2022-present), isn’t an allusion to these drivers’ tragicomic fates: it’s a narrative of how promises of purportedly new forms of technologically advanced labor are simply re-mystify long-standing colonial arrangements.

For nearly two years, Vitale’s consideration of automation bias has taken him to South Africa, a country whose apartheid history of mineral extraction was comprised of a transnational network of imported labor across Southern Africa. Rather than focusing solely on this classic exploitative form of accumulation through dispossession, he trains his attention on information technology and the relatively new but rapidly expanding gig economy. The Eurocentric conceit of automation, its organizing myth in the west, is that unmanned machine work makes life easy and efficient, freeing the western worker to follow other pursuits. But as Vitale’s multimedia work reveals, westerners have simply become further alienated from the globality of imported and outsourced labor—often in and from the Global South—that animates and sustains the operation of these machines, birthing a horrifying codependence: an asymmetry of benefit and oppression, and the near impossibility of untethering ourselves from the machines that structure the international labor landscape.

To find participants, Vitale used Upwork, South Africa’s then-most popular freelancing platform that connects clients and would-be workers. He studied the site’s communication, realizing the methodical marketing of insecure working conditions as freedom and the flexibility to work remotely. Subverting the exploitative tenor for recruitment, Vitale listed non-specialized jobs associated with the project and offered an average western European wage of 25-30 Euros per hour. He then created legally binding contracts off the platform, affirming the freelancers’ co-authorship of the project and guaranteeing 50% of any profits from sales of stills of their contributions. From scoring to translation to some of the content itself, nearly every person associated with the project (save the producer and second cameraman) was hired this way—and, in fact, the photographers in the show are some of these freelancers.

One of the artworks is taken from the film I Am A Human (“Ngingumuntu” in the isiZulu translation paired with all English captioning), which begins as a pseudo-documentary of South African mining—an almost caricatural praise of mineralogical richness and economic potential—and cuts to miners moving eerily in reverse. Always present, literally interpolated throughout the film, are the villainous wannabe geniuses Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk, the latter of whom derives his originary privilege from his father’s apartheid era mineral holdings. At the same time these tech oligarchs extoll green revolutions as the future of environmental sensitivity, we are forced to witness the ongoing crisis in the Democratic Republic of Congo in which paramilitaries and nation-states jostle for control over vital tungsten, tin, and tantalum mines (as well as the 2019 Bolivian coup, which Musk once copped to supporting to access the lithium needed for Tesla’s batteries). These minerals excavated by euphemistically named “artisanal miners” are at the heart of over two decades of brutal violence and catastrophic displacements in the Eastern Congo, as well as the operative organs of our consumer electronics. Here, Vitale uncomfortably juxtaposes these different registers of minimally regulated freelance work: the middle-class tech worker and the so-called “zama-zamas” (meaning “ones who try their luck” in isiZulu), unlicensed and illegal miners who occupy disused or operational mines in search of gold, manganese, coal, iron ore, and whatever else they can find.

GPS, 2022–ongoing. Courtesy the artist.

Though rooted in South Africa, the work gestures towards international machinations softened by Vitale’s filtering of this visual story of chaos: the deft cinematography and careful editing of this layered and collaborative work is the placid mundanity of freelance labor that belies a disorienting and destabilizing precarity. Images of the aseptic metallics of destroyed computer innards, the craggy surface of the excavation-gouged earth, and entrances into domiciles slyly collapsed into spaces of work are imbued with a deceptive aura of safety and calm. Verticality is the organizing orientation of racial capital: up is the direction of looming corporate skyscrapers stretching towards the heavens, and up is the direction of unbounded capitalist growth and the profits that follow. But guided by the dystopian technofuturistic visions of Musk and Bezos, as well as the interviews and footage of and collected by the freelancers themselves, Vitale’s directional vantage deliberately orients in opposition. His visual grammar of descent values messy conjecture over the authoritative “real” that is so often the domain of orthodox documentary practice, especially work about Africa(ns). But Death by GPS embraces the theoretical invitation of the School of Speculative Documentary and its proposed non-distinction “between fact and fiction, artifice and realism…[and] representation and experience.”

In its refusal to abstract the working and fatigued black body into inert and aestheticized taxidermy, Death by GPS is attuned to materiality, rhythm, and urban cartography. It recognizes and carefully engages the perpetual subtext of any present, post-apartheid interrogation of mining: the Marikana massacre, an expression of astounding state violence in which 34 miners were killed (and 78 injured) by South African police forces who fired on the workers on 16 August 2012 during a six-week wildcat strike. Taken on Vitale’s first day in South Africa back in July 2022, a photograph of a foregrounded white car partially obscures families and community members convening on the koppie (small hilltop) as a part of the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union’s commemoration of the miners who were killed in that same locale 10 years prior. In a snapshot of coalitional protest in Pretoria’s Union Square, red-adorned members of the South African Federation of Trade Unions gather in solidarity to struggle against the enduring apartheid setup of suppressed wages and poor working conditions for black people.

The anchoring near past nightmare of that fateful day in Marikana is punctuated by Bezos’ still-failed mission for space conquer, ossifying the negative relationship between his ascent into the cosmos and the miners’ descent into the ground. While whitey’s on the moon (to borrow Gil Scott-Heron’s titular poem) and Musk and Bill Gates self-indulgently dance and DJ celebrations of their own excellence, Vitale splices in the zama-zamas jigging and posing with their handguns and AK-47s. With this apposition, we are made to understand a singular economy through a hewing and viewing together seemingly disparate constituent parts: the opposites of the technological supply chain.

Descent, the dizzying down of the atrophic rot of capitalism, connotes the ungovernable and anarchic character of informalized labor and its undercutting of state profit through the funneling out of taxable of profits. It reveals the madness of the automaton-like human repetition of work produced by and with computer, the enmeshment and imbrication of the fungible African worker and its robotic counterparts—robota in Czech and other Slavic languages refers to serf/corvée or unfree labor, and more figuratively, the drudgery of labor subjugation or servitude. Rather than a headlamp, the zama-zama, snapped in his worn brown leather jacket, wears a striking goldenrod balaclava. To work, he lowers himself carefully into the opened ground with a tether. But his direction of motion is uncertain: the ambivalence of his ascent or descent mirrors the wider black participation in, skepticism, and undermining of insistent capitalist techno-optimism.

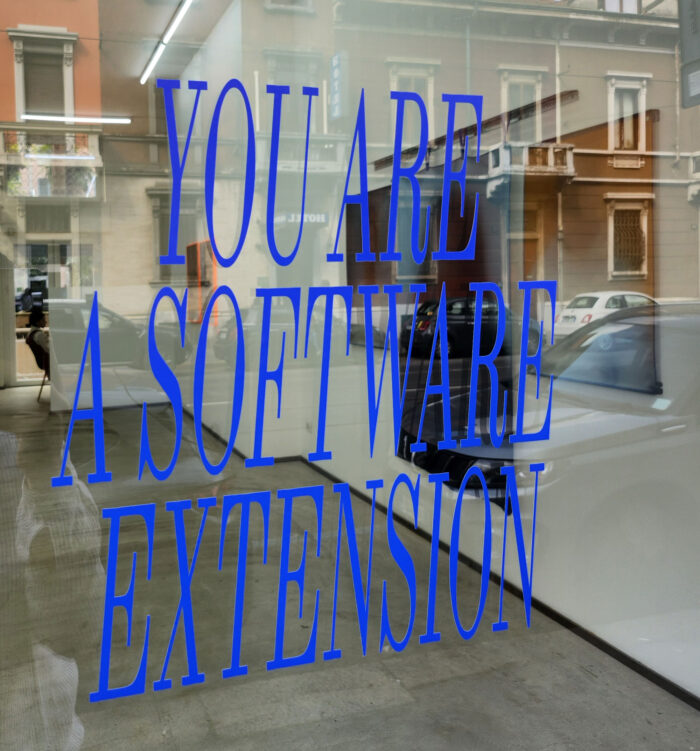

“Izinguquko ezinkulu zizofika maduze emnothweni we-gig,” reads neon blue isiZulu in the film; “Big changes might soon be coming to the gig economy” echoes the English translation beneath it. This reads far more as threat than assurance. Paraphrasing Upwork’s dystopian messaging, a sculptural form materializes this transnational intimacy. An African wax cotton print fabric-adorned Ikea Bleckberget swivel office chair reads: “Consider Automating. Hiring no Longer Applies to You.” Never a threat, but a new techno- reality.

But this is not all there is; Vitale’s work is far from nihilistic. Just as his photographic work constellates the spatialities of violence, it duly marks emancipatory horizons. The climactic “Listen All Y’all It’s a Sabotage” realizes what curator Legacy Russell theorizes as the glitch: a carving of space for oneself in the world “by broadening the realm of the unrecognizable” via “a political agent that adroitly threatens the capital of consumption.” These mobilized “microacts,” per philosopher Paul B. Preciado, include leisure and dance, play, laziness, and withdrawal, all the way to the 19th century English Luddite movement’s practice of destroying and sabotaging human worker-eliminating textile machinery. These dramatic explosions of office equipment—a Macbook, a printer, a server—are silent choreographies of pure catharsis. The films proceed impossibly slowly, their currency is anticipation: the damnable technologies rest on their altar-thrones before their spectacular combustions, honorific offerings before their obliterative sacrifices.

The machine can be used as a worker; but the worker is not, never will be a machine.