Poets, Out of Your Closets

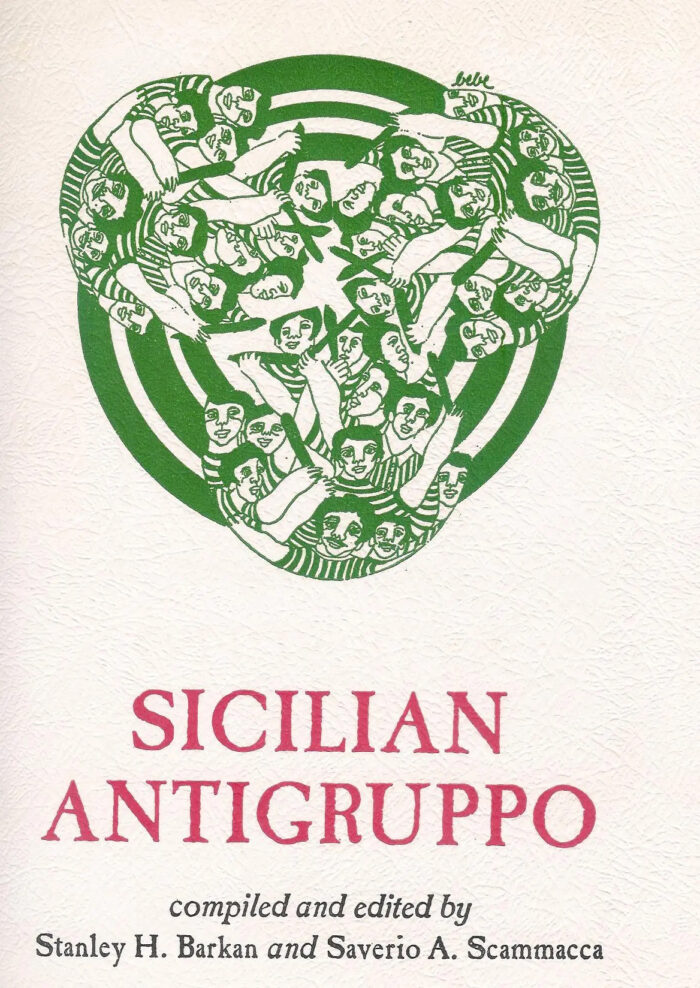

The transnational Antigruppo Siciliano

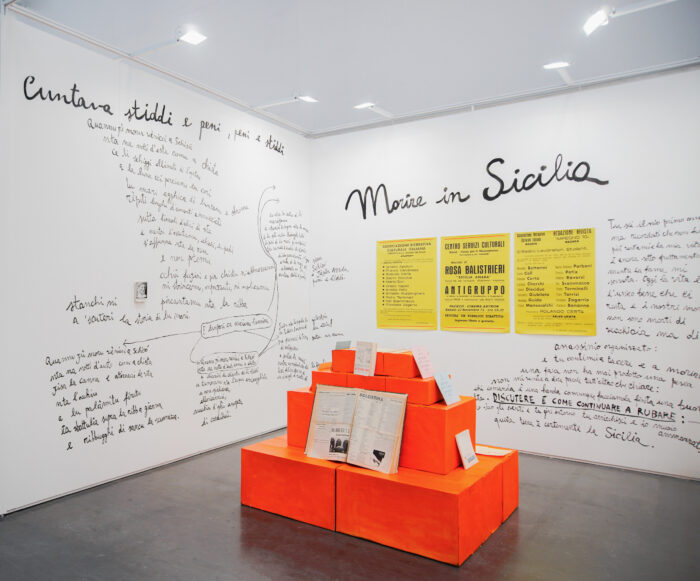

On the occasion of ArtVerona, REPLICA in collaboration with viaraffineria, Timo Perfomativo and Giuseppe De Mattia, presented a heterogeneous project on militant poetry, recounting the history of the Antigruppo Siciliano (Sicilian Antigroup), a poetic movement with great depth but still little known in Italy. Albeit in a concise manner, this article aims to tell the story of this group, placing the emphasis on its transactional aspect, to bring out their rich history.

The birth of a movement

We are in Ustica, a small town in the province of Palermo, at the end of the summer in 1968, autumn is settling in. T o the surprise and amazement of passers-by, a group of young people gathered in the square begin to read poems; one shouts them out, shortly after, others transcribe them on the walls of local fishermen’s houses.

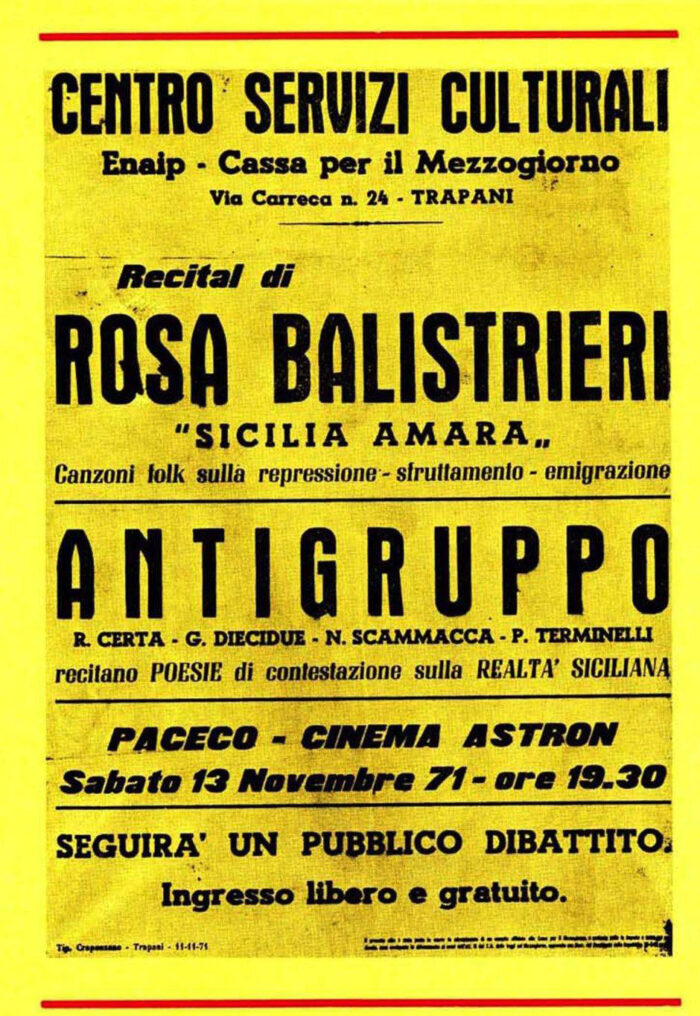

Thus was born the Sicilian Antigroup, following this first collective recital of poems in a sunny Italian suburb—an “anti” poetry movement consisting of a heterogeneous group of characters and distributed throughout Sicily, around three main locations: Palermo, Trapani and Catania. The group’s most active members were Crescenzio Cane, Pietro Terminelli and Ignazio Apolloni, Nat Scammacca, Rolando Certa, Gianni Diecidue and Santo Calì.

In order to understand the group’s internal dynamics, one needs to contextualize the movement within the experimental, underground and protest movements that flared out worldwide in the late 1960s. The thematic focus of the movement was poetry, along the idea that it could be a tool for action. It is precisely in the encounter between antagonistic action (praxis) and literary word (poiesis) that the members of the Antigroup detected the germ of an authentic cultural and political alternative.

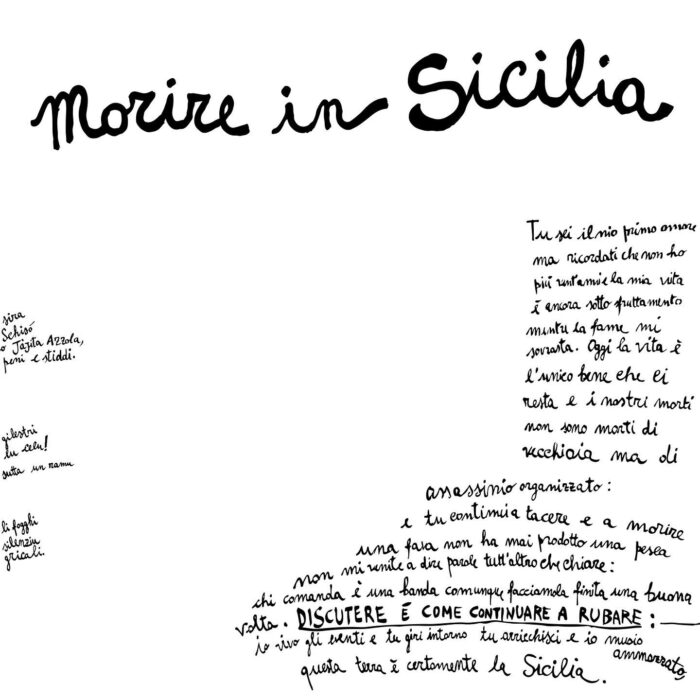

Seen as a spokesperson and the aoidos of society, the poet holds the gift and the responsibility to promote ideas of equality and freedom through their antagonistic voice. Only by uniting praxis and poiesis poetry is capable of becoming an action of social vindication. Only through opposition and voluntary exclusion from the dimension of constituted power is it possible to provide an alternative to dominant practices.

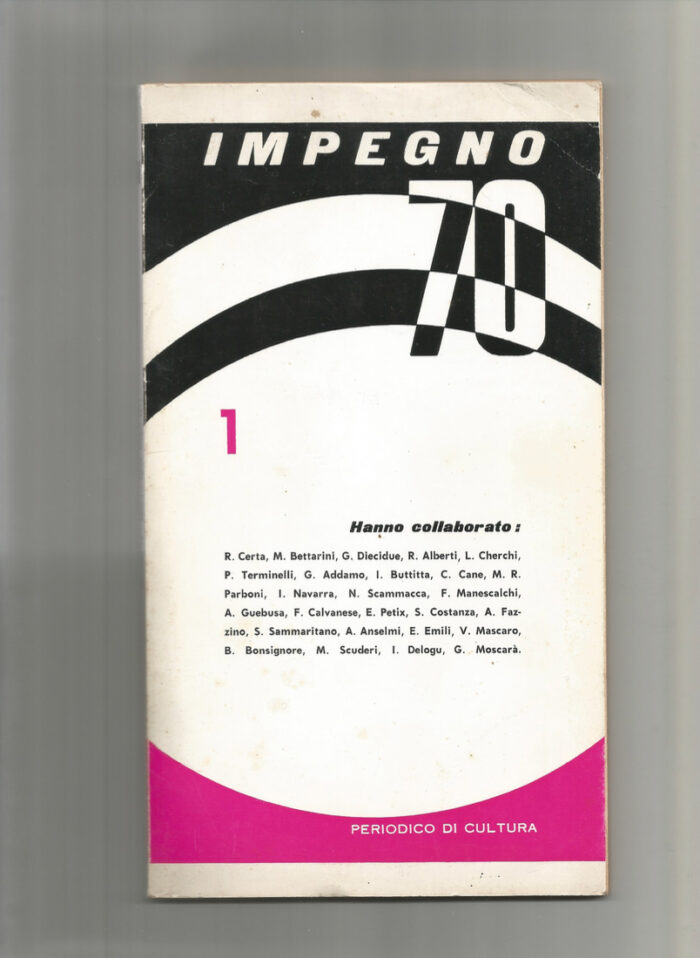

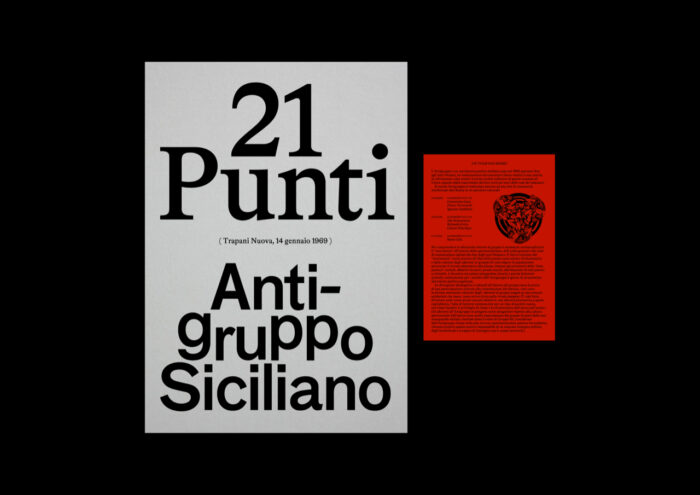

These are the reasons that drove the members of the Antigroup to position themselves as antagonists with respect to the experimental culture of the time, such as that represented by the group of poets of the Italian neo-avant-garde group united under the name of Gruppo 63. The Antigroup considered them to be close minded focusing merely on poetic-formalist research and experimentation, and therefore held them accountable for the intellectuals’ lack of political commitment and inability to interact with the working masses.

The Antigroup opposed the domination of cultural power and its structural components. One example is the publishing industry, linked to the logic of control of intellectual activity and responsible for the commodification of the cultural product. As argued by the Sicilian poets, the publishing industry subjects the figure of the poet to the dimension of a salaried producer of goods. This is the reality to which the Antigroup proposed an alternative model of literary dissemination, rejecting the logic of capital and therefore claiming its own autonomy in publishing terms.

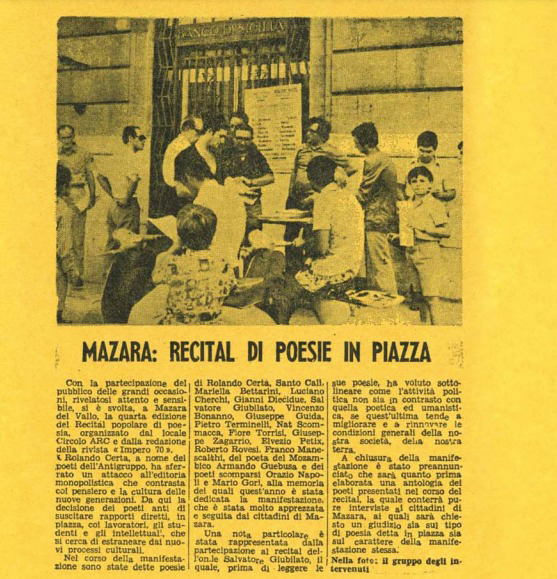

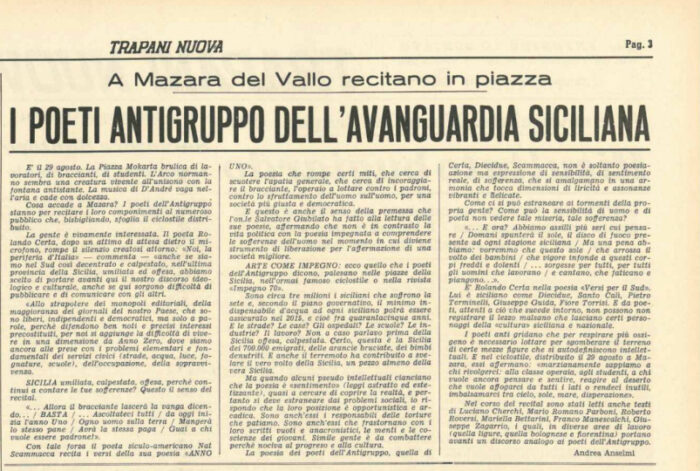

This autonomy is asserted and reaffirmed by actively involving citizens, directly addressing workers, peasants and students through a systematic recourse to the square, recitals, debates, meetings, the writing of wall poems and the distribution of mimeograph poems. The poets of the Antigroup constantly took to the streets to sing their poems in front of a varied, unprepared and always surprised audience.

Between 1968 and 1973, the promotion of public recitals was one of the fundamental activities of their poetic work, which always privileged the square as an open space. The square was seen as a book, as literature out of context: an ideal spatial dimension delimiting the field of their intervention. This activity across urban and country streets gradually became for these young poets a fundamental operation of anti-activity, for it is precisely the square that holds the power to legitimize the strength of poetry as a communicative fact, as an instrument of encounter and struggle.

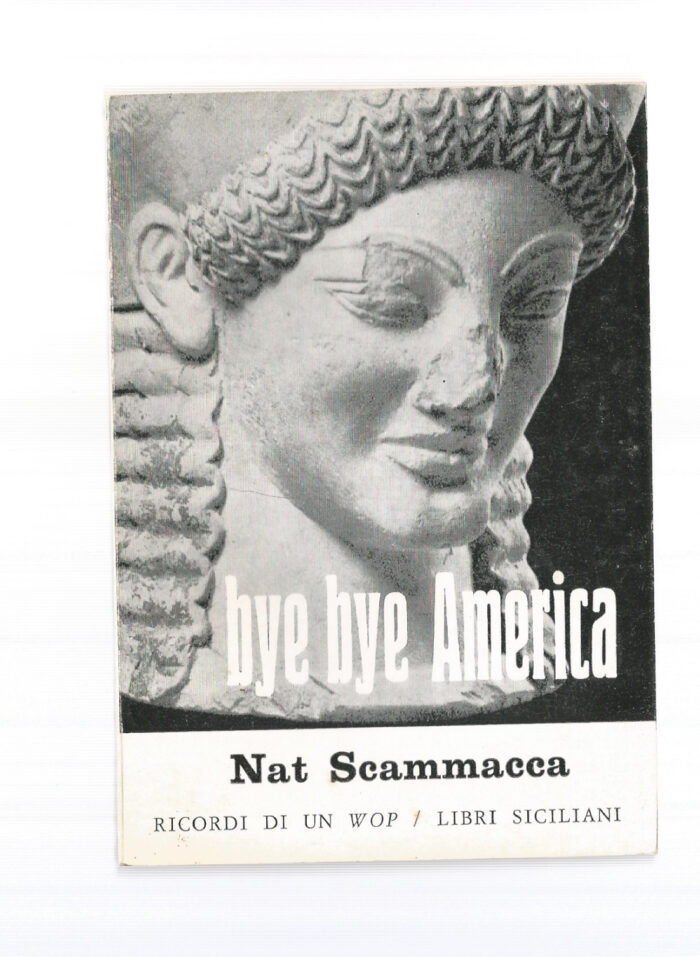

The poets of the Antigruppo made incursions into towns, villages, among the shanty towns and the evacuees of the Gibellina earthquake, holding their cyclostyled sheets of paper and wearing the brightly-colored clothes where they transcribed their poems. They festively met the people, who were moved by their words just as much as by the warm air of the island. In Bye Bye America, a prose book by Nat Scammacca, published with the independent house Coop. Antigruppo Trapani, an account reads: “And as we died every night to be reborn each morning, we woke up ready to enjoy a new youth; to open the window and see the bright rays of the sun splendidly strike the tops of the mountains again after the rain; giving us a new will to love, to hope, to be reborn in a world where everything is relative; where everything that begins unfailingly ends. Bury me, sing any requiem. I shall rise the same every morning and I will have some new reasons for yelling something: a display of paintings, poetry posters and anthologies, recitals of poetry in the blowing wind-shouting to the sky, to the mountains, to the people that we are alive! Yes, this is really life.”

The poets of the Antigroup not only had the piazza as their tool, but also independently built a varied editorial reality; in fact, they founded the magazines Impegno 70 and Impegno 80 the magazine ANTIGRUPPO, and had the third page, edited by Nat Scammacca, of the daily newspaper Trapani Nuova. In addition to this strong dissemination drive, it is worth mentioning the network of relations with American publishers such as Stanley Barkan, who distributed the movement’s themes and poems in the USA. It is legitimate to ask, but if in Italy this movement has received little attention as a local phenomenon, why instead was it—and still is—known overseas? The answer lies within one of the group’s founders: Nat Scammacca.

Bye Bye America

Nat Scammacca was born in Brooklyn in 1924 from a Sicilian immigrant family. In 1949, during a stay in Sicily, he fell in love with his cousin Nina, whom he married the same year. After years spent between Sicily and the United States, they decided to move permanently to Trapani in 1965. The first years were difficult, as Nat was homesick for America and dearly missed his colleagues, the poets of the Beat Generation. For this reason, he abandoned his wife and children to return to New York; soon, however, he became so remorseful of his act that he ended up in an asylum. It was behind those walls that Nat found a reason to retrace his steps. After recovering, he returned to Trapani to his wife and children. A few years later, he and a group of local intellectuals formed the Sicilian Antrigroup.

Scammacca is the one who most influenced the dynamics of the Antigroup. He is the one who coined Sicilian-American literature. He is the one who drew a manifesto inspired by the Beat aesthetic. He was the one who, for over thirty years (from 1967 to 1991), edited Terza pagina (Third page) of the newspaper Trapani Nuova; it was between the pages of this provincial daily that great writers and internationally renowned artists came by. Scammacca was also a supporter of the theory by English writer Samuel Butler on the Sicilian origin of the Odyssey, which he translated and edited in The Sicilian Origin of the Odyssey, a study by Lewis Greville Pocock, a professor of Classical Studies at Canterbury University College in Christchurch, New Zealand.

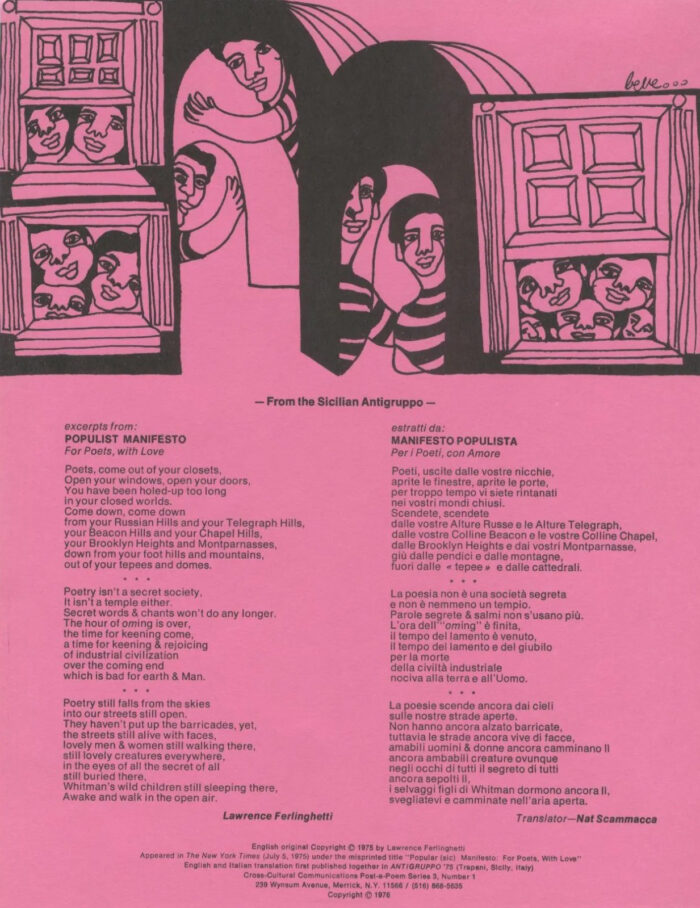

Scammacca is responsible for triggering a rich cultural exchange between Sicilian poets and Beat poets such as Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Jack Hirschman, popularizing “Anti” poems in the United States. It is above all his friend Ferlinghetti who was most often quoted and involved in the group’s activities. Ferlinghetti’s poems were translated by Scammacca and published in the volume Poesie politiche (Political poems); in the preface to the volume Scammacca wrote: “while Ferlinghetti proposes populism in California, I do the same here in Sicily. […] Populism is the underground of the common man and this common man, the young, the poor, the workers of the United States is the language that Lawrence Ferlinghetti uses, just as the peasant, the student, the Sicilian laborer is the language with which the Antigroup expresses itself.”

In the recent article La poesia Beat in Italia: uno studio translocal (Beat Poetry in Italy: A Translocal Study) by Alessandro Clericuzio, published in the academic journal Annali di Ca’ Foscari. Serie occidentale, a passage reads: “Ferlinghetti is often quoted in the activities of the Antigroup, whose manifesto appears to be directly inspired by Beat aesthetics: the recurring terms, in fact, are a ‘libertarian poetics’, a ‘new art’, ‘spontaneous’, ‘made by the people’, ‘art as experience’ and the artist as ‘revolutionary’, accompanied by a strong anti-hegemonic imprint and a particular attention to the oral aspect of poetry. In Scammacca’s words, it was ‘a group against groups, against the fascists, the mafia, the privileged establishment which […] collaborates to suppress the common man and his essential creative force’. Following a practice of public sharing of poetry, which was immediately perceived as one of the main characteristics of Beat lyricism, the Antigroup engaged in public reading activities. Its members traveled repeatedly to the Sicilian hinterland.”

In 1972, during the presentation of ANTIGRUPPO 73, the first book published in Italy with a cooperative formula, Santo Calì, a leading exponent of the movement, took the floor and read, alternating between English and Italian, a letter addressed to Ferlinghetti: “Dear Lawrence Ferlinghetti, […] it is necessary to prepare a book of Anti-groups in Sicily, with connections in Italy and the USA, which will make known to contemporaries and hand down to posterity, at least for a thousand years, how much we have worked for the dismantling of the cultural baronies—right and left—on the island! Sicily—and you know it, Lawrence—is the land blessed by Allah and cursed by Gianni Agnelli. Who, in these parts, represents the equivalent of your Henry Ford. […] Sicily Italy USA. A highly suggestive, provocative, allusive itinerary, mafia and consciousness-expeding [sic] drugs, the initiation rites to hallucinogens concelebrated to the sound of acid rock, the Citywide Women’s Liberation and the Gay Liberation Front. The Underground and the Movement… But the Sicilian Antigroup—believe me, Lawrence—is none of those things. Our counter-culture, our dissent, accompanied now by bursting enthusiasm, now by a profound and indefinable sickness, ignores extreme peaks of violence, murder and suicide, even the clamorous forms of advertising. Of American-style advertising, so to speak; even though at a recent ‘Palermo Pop 1971′ Ignazio Apolloni and Vira Fabra together with Nat Scammacca roamed the alleyways of the Mohammedan capital wearing multicolored shirts on which were conspicuously transcribed fiery poems against the establishment. We preferred to fight against the system by shouting—in the squares, in the worksites, in the schools—our proletarian rage. We participated in workers’ and students’ strikes, some of us have already crossed the threshold of prison for political offenses… Others that of the asylum. […] Undoubtedly: from the underground born from the beat scream to the politicized movement, the road to travel, at least here in Sicily, is still rough and long. But we also had to somehow set out on the road. And we have set out. […] I am convinced that even the experimentalism of the Gruppo 63 and the Sicilian-Italian neo-avant-gardes was suggested, provoked, dictated precisely by an immeasurable act of love. Because our drama lies precisely here: in blindly believing in the values of a logos revealing pure intentions that are then frustrated by a ruthlessly ‘real’ reality. […] Hello Ferlinghetti, by the standards of the entire Antigruppo 73 and its guests.”

A few years later Calì got to know his American colleagues personally, as in 1980 he hosted the poet Jack Hirschman for several months, who translated a collection of Calì’s poems into English Yossyph Shyryn. Years later, Hirschman would recall his meeting with the Sicilian poet as follows: “I’ve a long relationship with Italy. The title poem of my first collection, A Correspondence of Americans, first appeared in an Italian, not in an American, magazine, the rather extraordinary Botteghe Oscura in the late 1950s. In l980 a translation I’d made of a very great poet of Sicily, Santo Cali, was published in a bi-lingual edition in Trapani, Sicily. I am still amazed that Cali’s work is not better known as his lyrical and political strengths are among the very finest. He wrote many of his poems in Sicilian and that may be the reason for his continued obscurity, though I translated a book he had written in Italian, Yossyph Shyryn. In l980, after some months abroad working with communist, socialist and anarchist poets and painters in Sicily, where I traveled with the North Beach artist Kristen Wetterhahn, I officially joined the Communist Labor Party.“

This transnational aspect of the Antigroup was not only limited to relations with American colleagues: the voice of its members, as well as their desire to meet with the wider world, also emerged in the rich and foremost cultural dialogue established between Sicilian poets and painters with some areas of Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean. In fact, it is worth recalling the project promoted by the poet Rolando Certa, founder of the Centro per la cooperazione fra i popoli del Mediterraneo and organizer between 1979 and 1986, together with the Municipality of Mazara del Vallo, of the Incontri fra i Popoli del Mediterraneo (Encounters among Peoples of the Mediterranean), which saw the participation of 24 delegations from all over the world. The 1982 conference focused on the theory: “Let us get to know each other so that the Mediterranean may become a sea of peace and cooperation”, a theme that is perhaps more worth exploring today than it was then.