Planet Sex

Anna Franceschini on Davide Stucchi’s show “Falli-Phalluses”

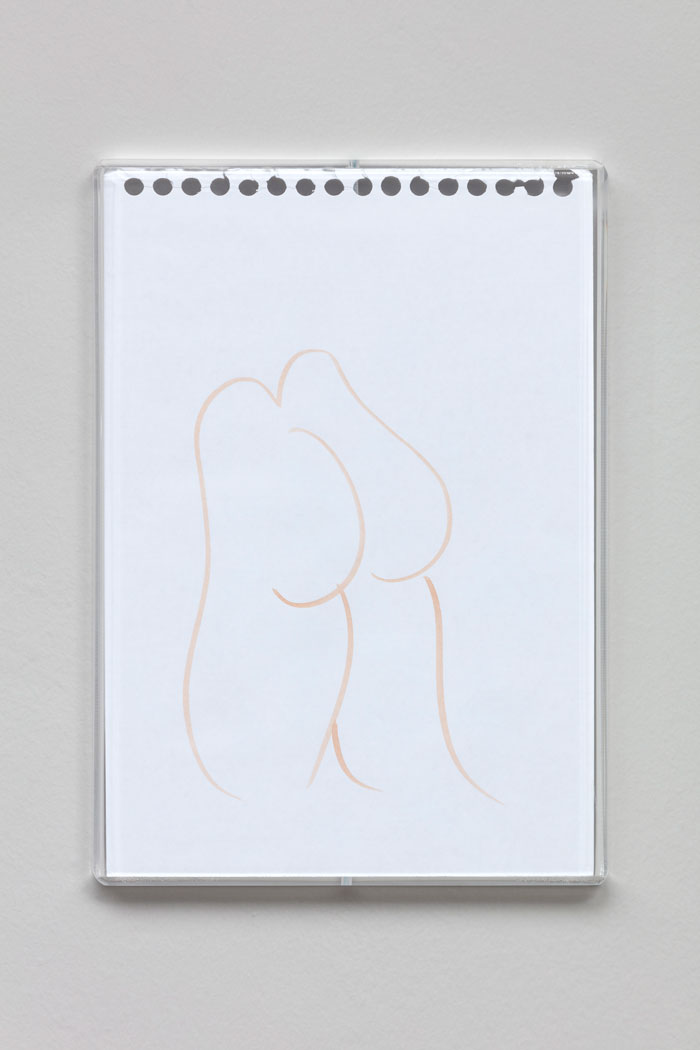

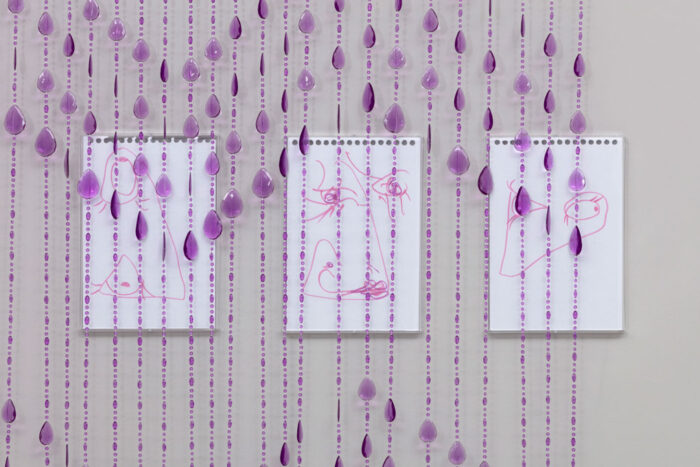

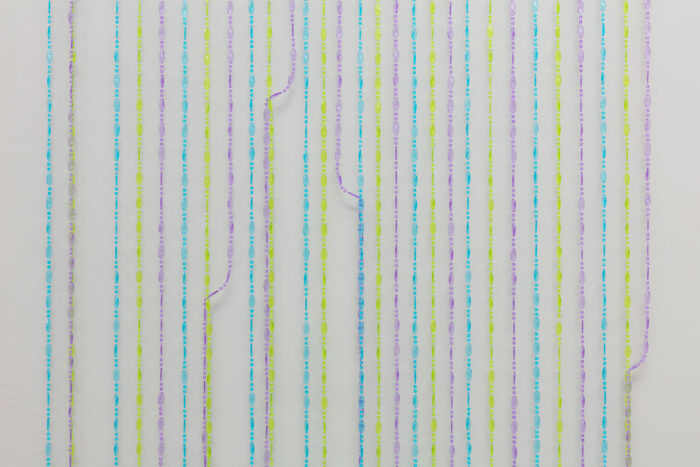

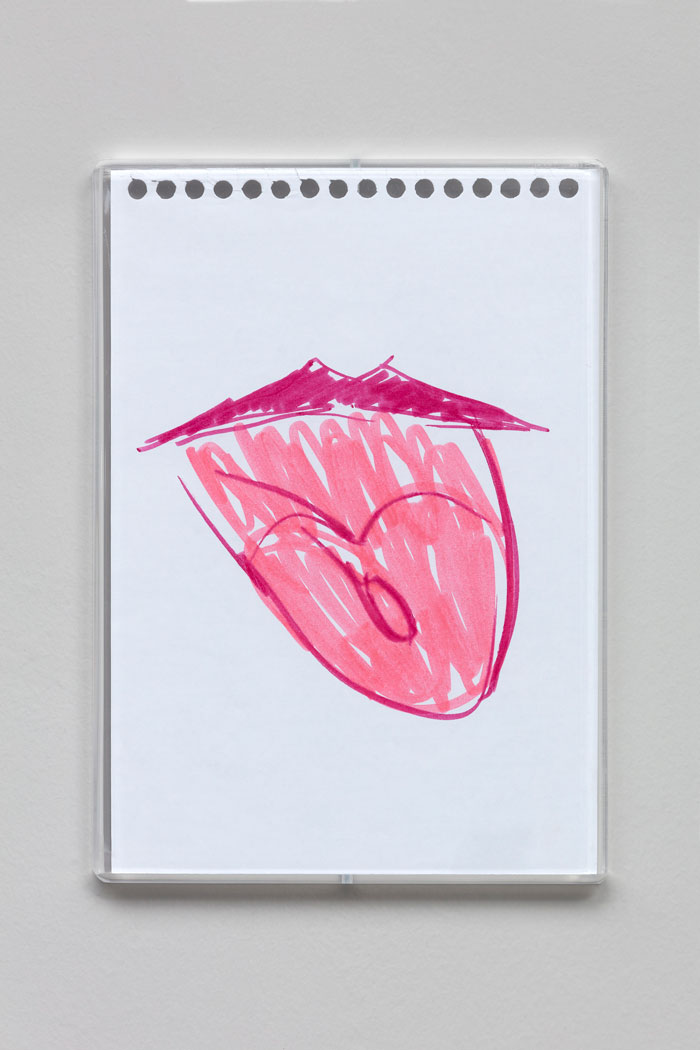

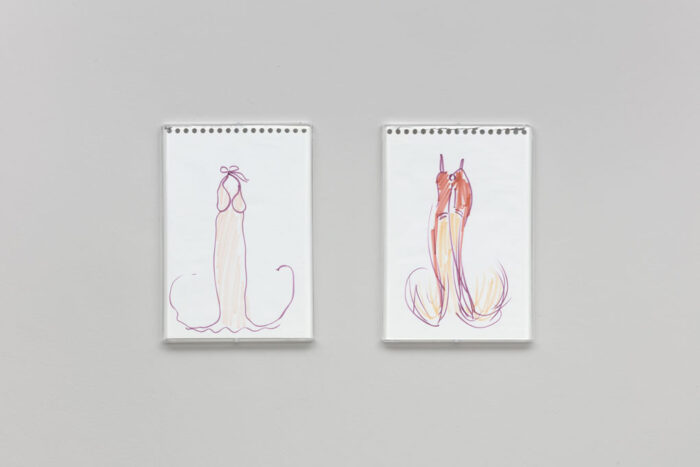

Falli (Phalluses) was the first solo exhibition by artist Davide Stucchi in Milan. The exhibition marked the opening of the new Martina Simeti gallery venue in Via Benedetto Marcello 44, in what used to be a sex shop. The title chosen by the Milanese artist pays homage to an exhibition by Walter Albini in 1977 at the Eros Gallery in Milan, where the fashion designer chose to poke fun at fashion figures and at fashion itself, presenting a series of sculptures of dressed-up phalluses. The installation proposed by Davide consists of a series of marker drawings on paper, a corpus he has been working on since 2013, going back to certain subjects and accumulating various versions of them. In just a few strokes, the drawings sum up allegories between desire and body parts, penises that form the fingers of a hand, buttocks, mouths, smiles and swimming costumes, as well as evening gowns worn by phalluses. Accompanying these drawings, a series of drapes evoke the atmosphere of PLANET SEX—the sex shop that occupied the gallery premises up until a few months ago—reconstructed through images found online, in which an acrylic curtain stood out leading down to the basement.

While observing some photographs documenting private residences made by Le Corbusier, architectural historian Beatriz Colomina, notes that men and women portrayed in the images assume, on different occasions, postures and looks that significantly diverge from each other. As Colomina states, “few photographs of Le Corbusier’s buildings show people in them. But in those few, women always look away from the camera: most of the time they are shot from the back and they almost never occupy the same space as men.”

The asymmetry of male and female gazes also persists in the architect’s sketches and drawings and, as the researcher points out, within the frame’s space it is added to the reiteration of a positioning of the characters that is determined by gender, whose canon indicates that “the woman is placed ‘inside,’ the man ‘outside’; the woman looks at the man, the man looks at the ‘world.’” The paroxysm of a tendency that Colomina, through her careful studies, sees consolidating before her own eyes, can be seen in a photograph of the chaise longue included in the photo collage documenting the exhibition of a living room and its furniture at the Salon d’Automne in 1929. Le Corbusier had worked on the project in close collaboration with designer and architect Charlotte Perriand, even including furnishings designed, made, and published previously by Perriand. Nevertheless, Perriand’s name is almost not associated with the design that is credited to Le Corbusier alone. Perriand is used, instead, as a model for photo collage, but, even in this case, her existence as the subject of the image is strongly jeopardized: “Perriand herself is lying on the chaise-longue, her head turned away from the camera. […] one can see that the chair has been placed right against the wall. Remarkably, she is facing the wall. She is almost an attachment to the wall. She sees nothing.”

Basically, in Le Corbusier’s imagery, women are “a-scopic” subjects, precluded from experiencing the world through their eyes. Not only they are de-subjectified, as in the case of Perriand, through the exclusion of facial features from the space of the image, but they are forbidden knowledge, the visual knowledge so dear to Corbusier, who defines himself as “an impenitent visual,” who exists in life only as a sighted person.

The gaze is a central element in modern architectural composition, and Colomina’s attention to the relationship between gender and the possibility of seeing allows her to articulate some important questions regarding the spectatorial condition—a hegemonic way of being in the contemporary world—and its incorporated relations.

Among the scopic grids that have the greatest impact on contemporary daily life, we can include a few social media such as Instagram, Tik Tok, Tinder and Grindr. The layout of these applications provides a significant recadrage of the screen, partitioned into windows that open onto the world, or rather onto the worlds of other users. Today Instagram—the social network that was born with a portfolio purpose and intended, in its initial intentions, for an audience passionate about photography—is today populated perhaps more by faces than by landscapes, although it maintains a balance between close-ups and wide establishing shots, views framed in long and very long fields. Inevitably less landscape-based are the dating apps, whose purpose is to give the possibility, to those who want to see each other and, perhaps, meet out there, in the world, to collect some information and mutual visual traces. Grindr, the well-known application for gay male dating, looks like a perfectly regular and functional grid. On the home page, a comfortable orthogonal layout cuts out a gallery of faces, interspersed with (a few) fancier images that may or may not have anything to do with the user’s personality. The image is only minimally smudged by the graphics: the name at the bottom and a green colored circle (to mark the presence), or transparent, (to sanction an absence).

Once you have chosen the profile to explore, scrolling down from the cover image gives way to a rather detailed anthropometric exegesis of the subject/object of desire: kilograms, meters, centimeters, colors. A less physiognomic and more aesthetic synthesis comes to complete the profile: the description of tastes, preferences and inclinations that uses a usual and shared form—I learned—to simplify a fruition not exactly similar to a gliding flight, but marked by elbow bends in the seething cauldron of desire. Geographical proximity is one of the most relevant traits in conditioning the choice.

As a user of the application, Davide tells me that he tried several times to use one of his drawings as a cover image for his profile, but that the image was rejected as “unsuitable.” In the work in question, Davide, in felt-tip pen, describes with a few nervous strokes on shorthand paper a male member, the vase with the long neck where a rose blooms in place of the glans. Although figurative, the drawing abstracts the organic and natural forms thanks to a quick gesture, a colored flicker. And yet the stylized penis does not manage to slip through the tight net of the app’s censorship grid, which does not allow the use of nude images on the cover, nor the representation of sexual organs. An infallible image detector grabs the flowered rod and throws it out of the decorous and windowed homepage.

The exhibition Falli at Martina Simeti Gallery in Milan gives form to Davide’s desire, repressed by algorithmic censorship, to show, to offer to the gaze, what most represents him: his art. Davide’s phalluses are everyone’s revenge on the optical respectability of an accelerated compulsion to desire. The artist disarticulates the functionalist grid and its serial import into the gallery space, where the regular format of the cell is maintained, thanks to the plexiglass cases that protect the drawings, but freed through encrustation. The happy environmental soiling is provided by five colored acrylic curtains, bare weavings of beads, memorial trace of the sexy shop PLANET SEX that occupied the gallery space until a few months before, whose deco traits have been recovered through an image search on the internet. The curtains are not only placed in front of some drawings, to the side or to mark thresholds more or less declared by the architectural structure, but they are modified with minimal gestures by the artist: knots, tangles, a small rearrangement of the transparent plastic bars’ inclinations.

As it often happens, [1] Davide’s intervention cannot avoid interstitial refinement, creeping into the peripheries of the gaze to demystify, by showing it, the logic of exhibiting. And the work, or rather the intense activity, on the leveling of the exhibition space are often linked to the memory that resides in the environmental minimalia. In this case, the rehabilitation of the decorative ornament constituted by the curtain re-establishes the relationships of proximity and distance between observer and work, subject of the gaze and object of desire. In Grindr’s greedy world of desire, geographical proximity is an imperative that surpasses empathy. In Davide Stucchi’s imaginary world, pregnant with desire, proximity to phalluses is charged with sympathy.

In its title and intentions, the exhibition pays homage to an unforgettable collection of 1977 at the Eros Gallery in Milan, created by the stylist Walter Albini who, unable to show his models, decided to dress them in sculptural phalluses and exhibit them. Both for Albini as for Stucchi, the disguise is the key to access a truth that is revealed with irony and lightness. The de-functionalization of the grid, like that of the penis, shows things for what they are—often nothing more than forms—and occurs not through a negation, a distancing or a denuding, but, rather, thanks to a new guise, an ironic masking that gets us even closer to the image. As art curator Lynne Cooke and film theorist Peter Wollen write in the admirable introduction to the volume Visual Display they edited, “it is only through display that truth is revealed—not directly of course, but obliquely and en travesti.”

Depatriarchalizing the phallus is no mean feat, at first glance it would seem an action destined to fail in a circular reiteration. We rack our brains trying to imagine the deconstruction, when Stucchi only needed a quick flash, with the tip of a felt-tip pen. In order to tear the penis away from the patriarchy, it was enough to dress it up—dress it up, make it into a fashion collection, beachwear, cruisewear. Reduced to a figurino (model), the figure explodes with a little-reverence beauty and ejaculates smiles.

If the scopic narrowness to which women are condemned, as Colomina points out, is still a loose end, it is fundamental that those who have always had the possibility of turning their gaze to the horizon, of filling their eyes with life, have the chance to look at nearby, everyday worlds, tiny windows that are much less scenic than those magnificently cut out by modernist architecture, with the irreverent openness that transforms the game of glances into the beginning of a loving complicity, of a tender and radiant friendship. With his metamorphic drawings winking among the multicolor flies, Davide Stucchi opens the door of the function cage, demystifying the rigor of the grid, showing what it is: one, only one among the infinite ways within our relationship with the world.

[1] See, for instance, Light Switch (Kitchen) of 2019, the precious intervention with an almost Duchampian taste in the space of the Exile gallery in Vienna, exhibited during the group show Molly House curated by Julius Pristauz in 2020, where a white interior switch interrupts the rhythm of the wooden perlinature that wraps the masonry and is animated by representations of bodies torn from illustrations of catalogs, newspapers and magazines, in turn enlivened by an external artistic and choreographic direction, since they are photographs of performers, dancers and models. Or the lighting gesture Light Switch (The Guy Next Door) at the 17th Quadrennial of Rome, still in progress: LED lights wrapped in bubble wrap lying on the ground and, constantly, almost on the verge of being removed by the maintenance staff, stealthily contribute to the illumination of the environment and of the other works on display.