Paintings for Nothing

Nostalgia, humor, neurosis, banality and the obsessive pursuit of innovation

Liquid Products and Frozen Form is the first Italian exhibition of the American artist Joshua Miller (1981, Colorado, United States). Seven large canvases will lead the spectator on a path that, exploring the phenomenology of the visual language, assumes the form of an imagery atlas that will tell the history of painting. Drawing inspiration from popular culture, Miller paints simple and everyday objects with an unusual and original approach. The artist experiments with old techniques and juxtaposes varied pictorial styles to obtain an emotional and expressive structure which exposes the entire range of moods and personalities inherent to painting.

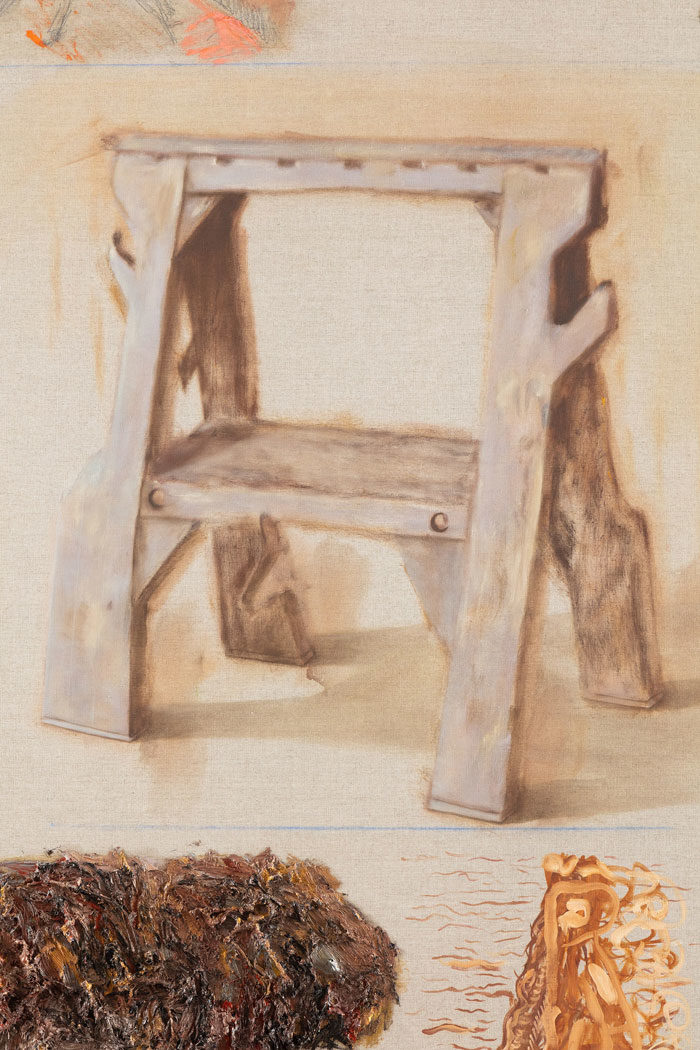

Alessandra Giacopini: In Liquid Products and Frozen Form—your first exhibition in Rome—you presented seven large works that showed us a variety of simple and repeated objects, which are painted with different techniques and displayed on regular grids: mouse traps, saw horses, golf courses, and sporks are just some examples. The choice of your subjects is particularly interesting because they are totally different from each other and they are sometimes unusual or even unnecessary objects. How did you choose them and what is your relation to them?

Joshua Miller: I keep a long index of potential works on file and continue adding to them as I come across new subjects that have potential. There are several different paths of thought which generate new subjects but one of them is an interest in etymology of everyday subjects and colloquialisms. For example, we all know the phrase “Best thing since sliced bread” but none of us know when that phrase showed up or when sliced bread was invented. That becomes a thing to look up, which becomes a curiosity about bread slicing machines, or bread loaf shapes, or leavened bread varieties, and then a painting feels like the best way for me to become intimate with the subject and share that knowledge. I’m old enough now to have spent a lot of emotional energy trying to make sense of big questions in life only to find very few answers. So now I spend more time looking at simpler things. If I ask a narrow enough question, I might get an answer that I can use and build on. That’s one reason why each painting is narrowly focused on a single subject. I’m still interested in big topics, like industrial farming and food production, but a topic like that is so complex and full of interdependencies that I prefer to take a more asymmetrical or granular approach.

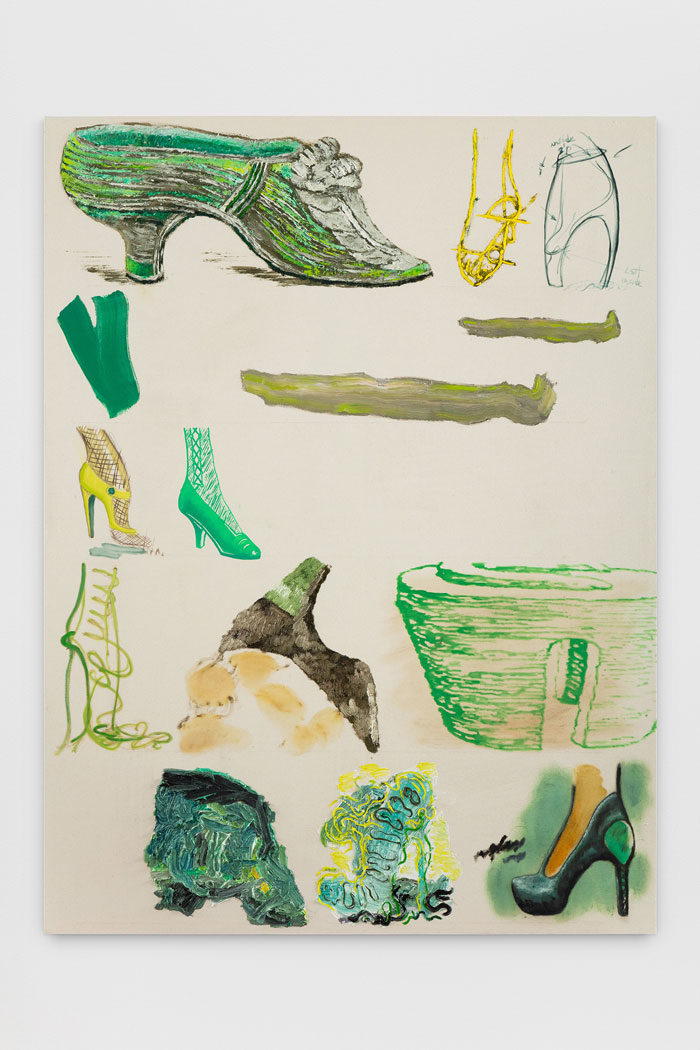

Sometimes my subjects come from the need to put to rest an annoying desire or repulsion. It’s like a nervous tick, the desire to draw genitalia or a swastika. So, if I just make one painting full of them, categorized and quarantined, afterwards I feel like I don’t want or need to ever paint one again. I’m able to dive completely into something but keep it from infecting me or the rest of my work. After that I feel a sense of mastery, I’ll only paint the subject again if there is highly specific need and I’ll do it with a strong understanding of what and how it signifies because I will have previously spent an entire month painting the subject repeatedly on a canvas. There could be a subject that I have a disdain for such as fashion sketches or architectural sketches, making a painting of them forces me to learn from them and form some empathetic bond with the people who make those kinds of sketches. After I finish the painting, I feel like I’ve experienced a bit of their lives and passion, I understand it and see its merit.

Joshua Miller, Utility and Apathy, Shoes, 2018. Photo by Evan Bedford. Courtesy T293, Rome and the artist.

French sociologist and philosopher Jean Baudrillard stated that “to overcome an idea is to deny it; overcoming a form is going from one form to another.” Are your products liquid in the way they change shape and significance by the technique you use to represent them or by the gaze of the viewer? Is the technique the main character of your story or, on the contrary, the gaze of the public is?

I think the meaning and utility of objects and images are liquid. When we interact with them, they freeze for a time and then they change again, so our relationship to their meaning is always in fluid movement. Objects go from being functional to collectible, and they go from new, to kitsch, to antique, and then back again. They also move from being true and useful evidence to totally subjective.

The changes in painterly technique that happen in my painting carry meaning but they’re also something I indulge in to keep myself engaged in painting. My approach is a byproduct of living in an age of overstimulation and fluid identities. I’m interested in how we position ourselves against the work and how we attempt to grab onto some firmness of meaning; the tensions of that comes from the gaze, as you put it.

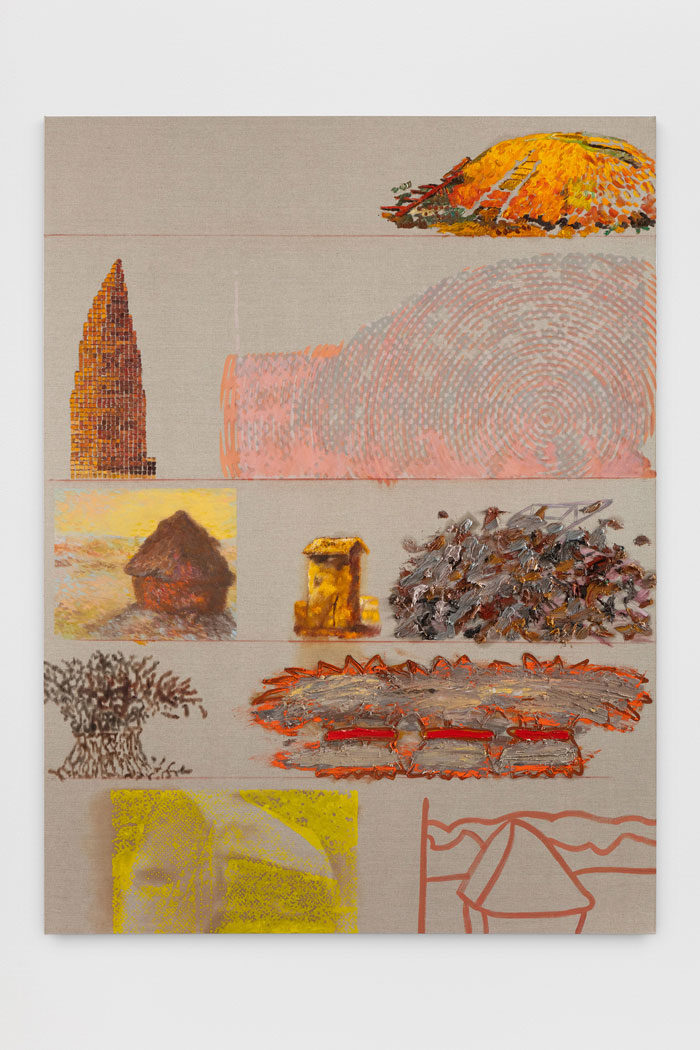

Joshua Miller, Haystacks, 2019. Photo by Evan Bedford. Courtesy T293, Rome and the artist.

Are you working on the dematerialization of the object or on its concrete materialization?

I think I’m interested in that transition between where an object loses or gains it meaning. If we’re on a tightrope balance is a very clear thing, you’re either on or off the rope. But with visual representation its infinitely more complex, a painting of a familiar object can lose or gain its identity with the addition or subtraction of a single mark, shadow, intonation, etc. I don’t understand why representation is so fragile, but painting is perfect for exploring its fragility. When I paint an object sometimes I’ll try the most backward or hindered approach I can imagine, then as I work I watch for that first moment when the object is potentially intelligible and stop there.

What’s your main source of references: your daily life or the Internet? How is your painting affected by the source you take inspiration from?

Up until a few years ago I painted exclusively from physical objects that I’d collected. I was and still am opposed to painting from a 2D image because so much information and curiosity is lost. When I paint a figure from life, I think about its unseen sides and figure it into the painting, but when I paint a figure from a photo, I only think about spacing and direction of marks 2 dimensionally. I’m frustrated by the amount of digital or print sourcing in this recent body of work, but it’s the only way I can manage to get to the range of subjects I’m curious about. I think it will take many more paintings to understand the difference between painting from solid objects vs 2D images, but it’s probably something cognitive in terms of how we physically relate to it.

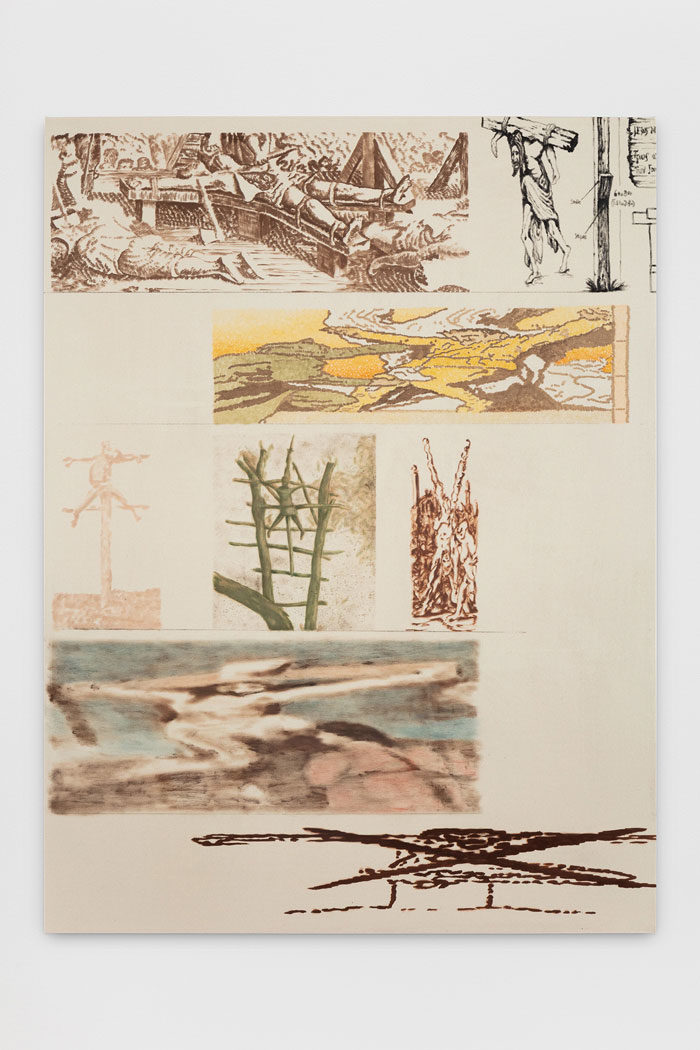

Joshua Miller, Crucifixes, 2019. Courtesy T293, Rome and the artist.

Can you tell us something about the title of the exhibition?

The title is an inversion of a sentence I read in a scientific abstract about music’s use value as it evolved from a folk practice to a modern commodity. The argument they made was that songs are inherently liquid, for thousands of years they were never written down or owned, just passed around. Only during the 20th century did the record label era attempted to make them solid through copyrights so that money could be made, but the era of remixes and digital tools to access and play with songs is returning music to its liquid form. So in the remix age songs are “frozen products in liquid form,” they freeze for one part of our cultural awareness but then also exist in liquid “remix” form.

I thought this applied to visual representation, the complexities around signifier/signified and subjectivity. It seems like those language lessons we learned from Magritte or Kosuth are, and maybe always were, way out of date. In the last 30 years we’ve become much more sensitive to the complexity of language, representation, and subjectivity. We care about what something is called and who gets to call it that way. Part of my paintings’ work is to grapple with that complexity, and the title is to point to the general uneasiness around the increasing liquidity of meaning.

Joshua Miller, Liquid Products and Frozen From, 2019. Installation at T293, Rome. Photo by Roberto Apa.

Joshua Miller, Liquid Products and Frozen From, 2019. Installation at T293, Rome. Photo by Roberto Apa.

Looking at the show, I would say that there are three topics that define the entire production: change, freedom and nostalgia. First, the change of styles reflects a change in the history of art and it’s related to your feelings while painting; secondly, the objects are painted without a hierarchy and the viewer is free to move from one to another without any conditioning; last, there is a sense of nostalgia along with your atlas of images that is related to the history of painting. What is your point of view?

I want these paintings to give me freedom to move between subjects, styles, techniques, and I want the freedom to be boring. I’ve built a structure that allows those freedoms. Reading Beckett’s Texts for Nothing #4 once a year helps me stay confident in the value of boredom, and emptiness, and talking without trying to force out a conclusion. I also don’t care so much about displaying compositional skills or entertaining the viewer in that way. Actually, I find composition to be one of the most boring parts of making art and too many artists give too much of their works’ meaning over to compositional demands. What I found by giving up traditional compositional energies is that the viewer has an easier entry into the work; there is a democratic feel to the images that you’re allowed to get part of it without getting all of it. At the same time the organization makes the painting feel quantifiable and that keeps us engaged in an attempt to add all of these images up.

The raw canvas and linen lend a nostalgia, as does the earth tone pallet that I favor. I did that to calm the viewer down, as the subjects I chose can often be visually painful (crucifixion, penis subincision) or painfully dull (sporks, haystacks). I also have a strong resistance to the contemporary pallet of industrially produced primaries and secondaries. Maybe it has to do with living in California, but I feel overloaded with bright plastic colors. It makes me a bit sad, because I feel like the graphic design industry and industrial printing has overrun the sensibility of painters. We think our paintings have to compete with movie posters and tennis shoes, bright colors and sweeping diagonal lines. Our paintings should be going in the opposite direction, there is already enough of that stuff in our daily visual lives.

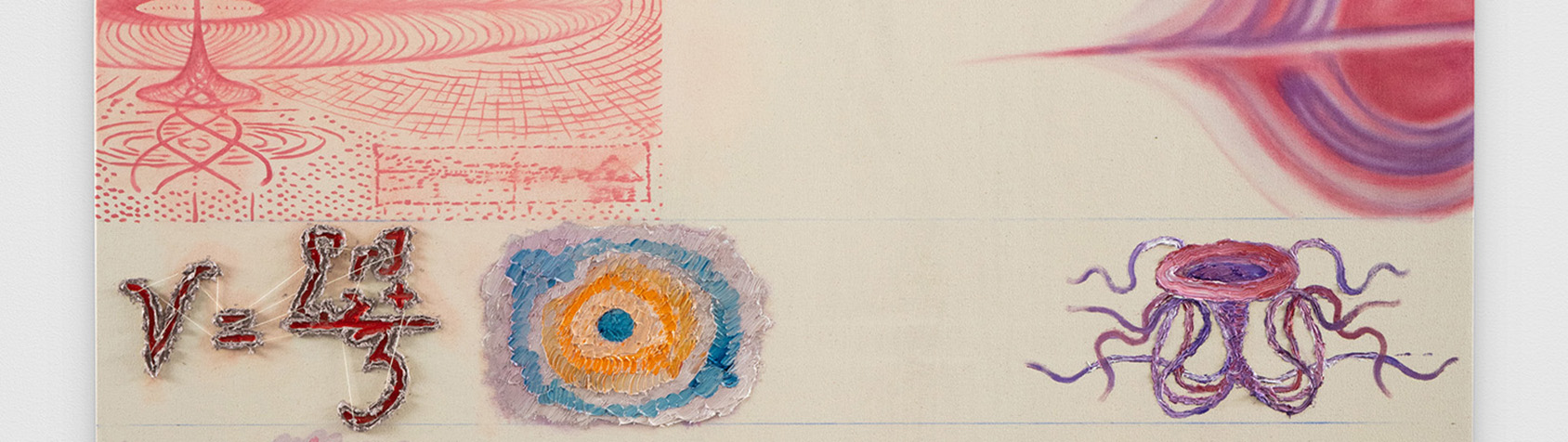

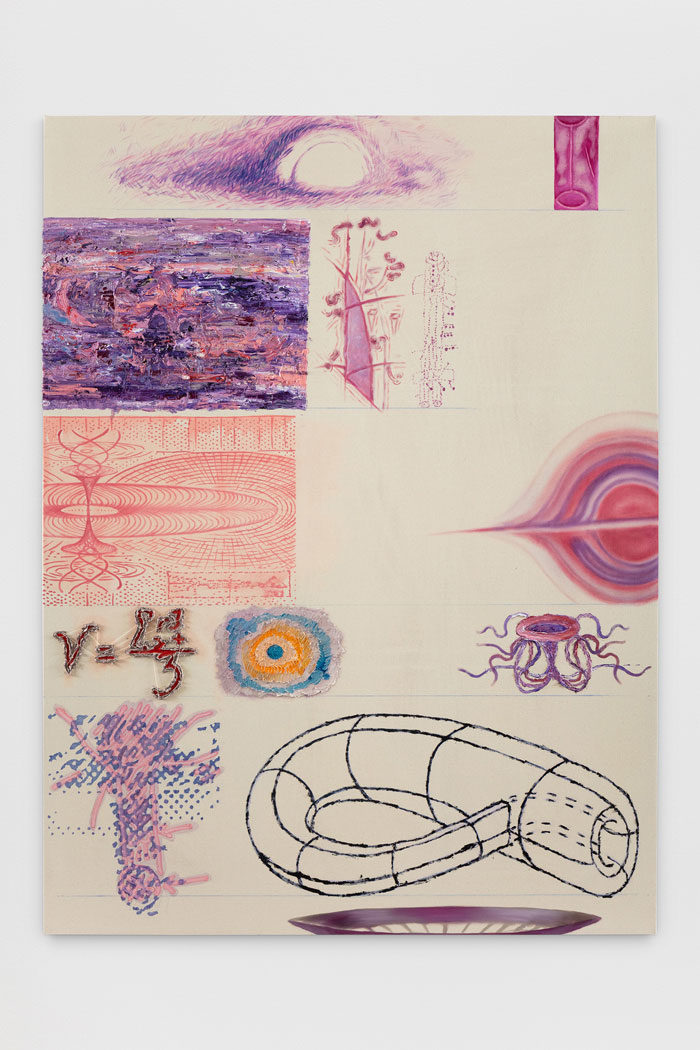

Joshua Miller, Black Holes, 2019. Photo by Evan Bedford. Courtesy T293, Rome and the artist.

Another aspect I would like to take into consideration is related to the Black Hole painting. In this work you wanted to represent an incorporeal element, which is strictly hard to be defined, and so you present it to us with different levels of interpretation. This reminded me of Joseph Kosuth’s work and his choice to use the linguistic approach to describe an idea and to investigate the contexts—cultural, social, economic, and political—in which art is shown. What is your approach to “abstraction” and what is the role of the scientific context in this case?

For me, the most surprising thing about this body of work is to watch fundamental art concepts, such as abstraction and realism, morph and break down when applied to unfamiliar fields. I like forcing “Fine Art” and “oil on canvas” to contend with subjects and areas it’s usually sheltered from.

Black holes are a strange meeting point in the imaginations of cinematographers, physicists, astronomers, and science fiction lovers. They’re seductive, incomprehensible, dead matter. Attempting to paint them helps me understand abstraction as a meta form of communication and analysis rather than a narrow field of fine art. Just looking at mathematical equations I realized that a given equation can only describe a narrow aspect of what a black hole is, one formula for its mass, another for its density, another for its event horizon, and another for its gravity. Each equation is an abstraction attempting to communicate an idea. Understanding “abstraction” in that broad and boundless sense opens new possibilities of what art, abstraction, or representation could be for me.

Joshua Miller, Saw Horses, 2019 (detail). Photo by Evan Bedford. Courtesy T293, Rome and the artist.

Is your painting a praise of the objects or a criticism of consumerism?

I don’t want to make a consumer critique, but I think it’s important that it’s brought up. Consumer critique is what frustrates me about Haim Steinbach’s work, I can never get to poetics with his work because the presence of the objects and the resulting consumer critique is so overwhelming. In my work, the insistence in oil on canvas is a way to keep the viewers relationship to the work warm and poetic, its grounded in a long romantic history of painting. There is a critique though, and it’s of the technocracy, especially America’s technocracy. Some of the works reflect on a system of endless innovation. The paintings are a way to overlay the pursuit of technological innovation with the pursuit of artistic innovation, and then see how those pursuits resonate.

This is your very first exhibition in Italy and T293 is the first gallery to represent you. What brought you to choose an Italian gallery and what are your impressions of the Italian art scene?

I’ve followed T293 for several years. Puppies Puppies and Martin Soto Climent had my attention especially, but the whole program has a wonderful combination of conceptualism, poetics, visual magnetism, and empathy. It’s a setting where the human potential of the art seems primary rather than art’s commodity value. T293 felt like the perfect way to introduce my work and concerns to an international art community. I think those values also come from the fact that T293 is in Rome. Rome’s cultural value to the world is central but miraculously the city isn’t over-run by modern capitalism. Italy also has amazing art publications and it’s a place where the “metaphysical” is taken seriously. I think at first it sounded funny to me but the more I’ve heard Italians talk about visual art the more it seems that they manage the correct balance of romance and intellectualism. The intellectualism somehow seems more true because it is grounded in something vibrant rather than the cynicism I’m familiar with in the US.