Memory Game(s)

On how to address tradition, incorporate re-invention, enabling the past to percolate the present as an ongoing unfolding into the future

The exhibition MEMORY GAME presents the different ways in which contemporary artists respond to geography, history, trade and economies: craft, tradition and re-invention, geopolitical structures and networks of power, transaction and exchange, economies and histories. A number of these artists have responded directly to the ideas underlying the exhibition by making work specifically for it. The matter of archives and of how to respond to collections are present as real and urgent questions in each artist’s contribution. In Life: A User’s Manual, Georges Perec outlines the impossible task of attempting to list forgotten words. Ironically, the name of the person doing so, Cinoc, is not a “real” name, but one arrived at through layers of mishearing what in living memory was already a name given through cultural assimilation.

This exhibition is curated by Dr. Jo Melvin and Vittoria Bonifati with the support of the Fondazione Dino ed Ernesta Santarelli.

“I think memory game is a very raw show

That fits the times

The beauty is in the starkness and the cleverness of the selection

It matches the space very well

I’m not surprised the newspaper person could not see it

Culture and journalism don’t mix

It is supreme culture when the raw can be made beautiful by orchestration

I hope it is realised what you are doing and how capable the delicacy of such a show is.

From Hiller to the wood chip, wood chip mix to oil mix which makes marbled paper…

Paper, even water and oil, to marble

Marbled or mind boggled

Traces across mountain of rock to glass structures, pattern on pattern

I wonder if they see

Circles of thought,

Bits, scraps which are kept and re-used

Sounds of trying

Lost echoes of impossible things to grasp

This is what is achieved

Puzzle of the head

Card games introducing curatorial sympathy for the mad artist endeavour

Why do they do it?

Yet

Because

It is for this kind of moment of precision”

Reflections on a train after seeing Memory Game at Villa Lontana on 24.9.2020 by Jeff Gibbons

The starting point for the exhibition MEMORY GAME is a nineteenth century chest of drawers comprising numerous coloured marble samples used during the Roman Empire. The object is part of the Fondazione Santarelli Collection, which is treated as an archive to develop the curatorial projects of Villa Lontana. Each sample comes from a different quarry and location within the extended colonies of the Roman Empire: Afghanistan, Algeria, Egypt, France, Greece, Italy, Jordan, Libya, Macedonia, Spain, Syria, Tunisia and Turkey.

The chest of drawers is an object that provokes us to think about geographies and memory games in conjunction with the political, economic and geographic expansion of the ancient Roman Empire. “Those who still wander around the Palatine Hill, the Forums, the ruins of the baths and other monuments, will see small flakes and fragments of various kinds of coloured marble, standing out among the stones and the loose earth, especially after the rain. These fragments are not stones originating from the soil of Rome, but come from all parts of the Empire.” This passage comes from the seminal text Marmora Romana, written by Raniero Gnoli in 1971 after his visit to all the main places and monuments of the Mediterranean basin where there are ancient marbles, retracing the paths of Faustino Corsi.

Rome is a city built on tufa and travertine. Coloured marbles were imported by the Romans from around the Empire, creating an artificial geology which then became the symbol of Rome abroad—even if not originally autoctonous to the city. Disks, squares of serpentine, porphyry, slices of columns, repositioned to live in other forms and other bodies in a continuous transhumance from Rome to Constantinople and beyond. The stones move: they move from one building to another, from one city to another; they are reborn, they do not age and never die. The history of man is accompanied by the movement of stones and those who love stones find in them the secret soul of the earth.

The chest present in this exhibition, attributed to the Belli brothers, is comprised of fourteen drawers containing 560 samples of coloured marbles. It was common use in the 1800s for these marbles to be dug out of the earth and then cut to make such ‘campionari’ (furniture). The chest includes all the types of marble used during the Roman Empire, each coming from a different quarry and location within the extended colonies of the Romans, mapping geographic territories and networks with histories and memory. The enormous quantity of stones transported to Rome from all the regions of the then known world entails a complex organization, ranging from the workers involved in quarries and transport, to the reception and distribution offices in Ostia and Rome. During the Republic, the quarries were all privately owned; later on, the most important ones became part of the imperial patrimony either by conquest, purchase or inheritance. The introduction of many foreign marbles dates back to the end of the Republic. Marble became a form of propaganda, where the use of certain stones signified the conquest of certain regions. The workers inside the quarries were mostly slaves or condemned (dannati ad metalla) both for common crimes and, at the time of persecutions, for religious reasons.

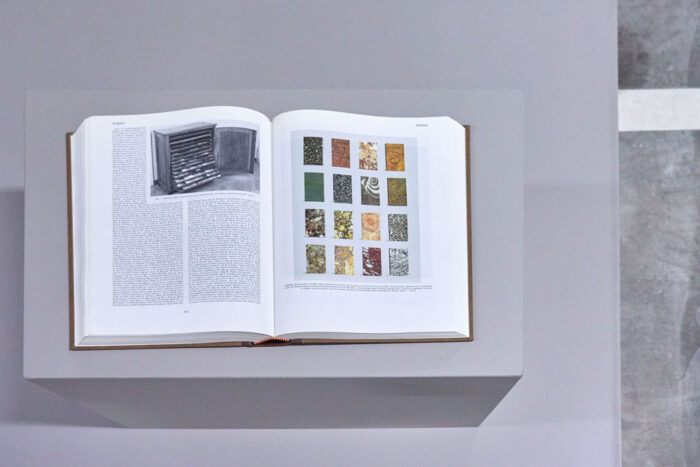

The first edition of the Enciclopedia dell’Arte Antica Treccani (known as the Treccani Encyclopaedia of Ancient Art) was published in 1929; in a later edition from 1995, the definition of the word ‘marble’ is accompanied by a photograph of this very chest of drawers (previously in Franco Di Castro’s Collection) present in the Santarelli Collection, which is in itself a collection of marble statuary and coloured marble fragments.

Paola Santarelli used this chest to devise an imaginative game of memory, which she played with her children. They had to name the samples by sight and match their locations, without turning them over to check. The chest was devised to render a catalogue of the richness of the quarries’ product and simultaneously to show how the samples look and feel, giving the viewer a tangible experience of their qualities. The furniture—drawers, chests, display cabinets—made to contain and present their collections of objects (organised by type, source, colour, etc.), belongs to the tradition known by the German word “Wunderkammer”, generally translated into English as “cabinet of curiosities”.

The city of Rome can itself be thought of as an archive, with numerous sets of drawers containing various “Wunderkammer” collections of architectural periods, dating back to the pre-Roman Etruscan era, or even earlier, to the times of its agricultural territories—along the banks of the River Tiber. The Tiber’s underground tributary rivers continue to flow below the city. The objects, with their personal and/or cultural value, become embedded in the fabric of the city to which we, as its current inhabitants, add the experiences of our times with their varying and different values. Our personal, collective and cultural memories form part of the rich metaphorical sedimentation of the city and its continuous evolution, which we can set out in parallel with it geological and geographic specificities.

The threads shaping the parameters of MEMORY GAME include how to address tradition, incorporate re-invention, enabling the past to percolate the present as an ongoing unfolding into the future, and how personal memories and experience converse with and connect to sediments of place and geography, geopolitical structures and networks of power, migration, cultural absorption and the economies of value. These values embrace ideals of beauty, notions of craft and economies of trade.

The chest of drawers, together with the Enciclopedia dell’Arte Antica Treccani are presented in Villa Lontana’s garage space alongside works by Tauba Auerbach, Cyprien Gaillard, Susan Hiller, Thomas Hutton, John Latham, Charlotte Moth, Rosalind Nashashibi + Lucy Skaer, Olu Ogunnaike, Giorgio Orbi, Andrés Saenz de Sicilia + Emiddio Vasquez, Edoardo Servadio and Joëlle Tuerlinckx.

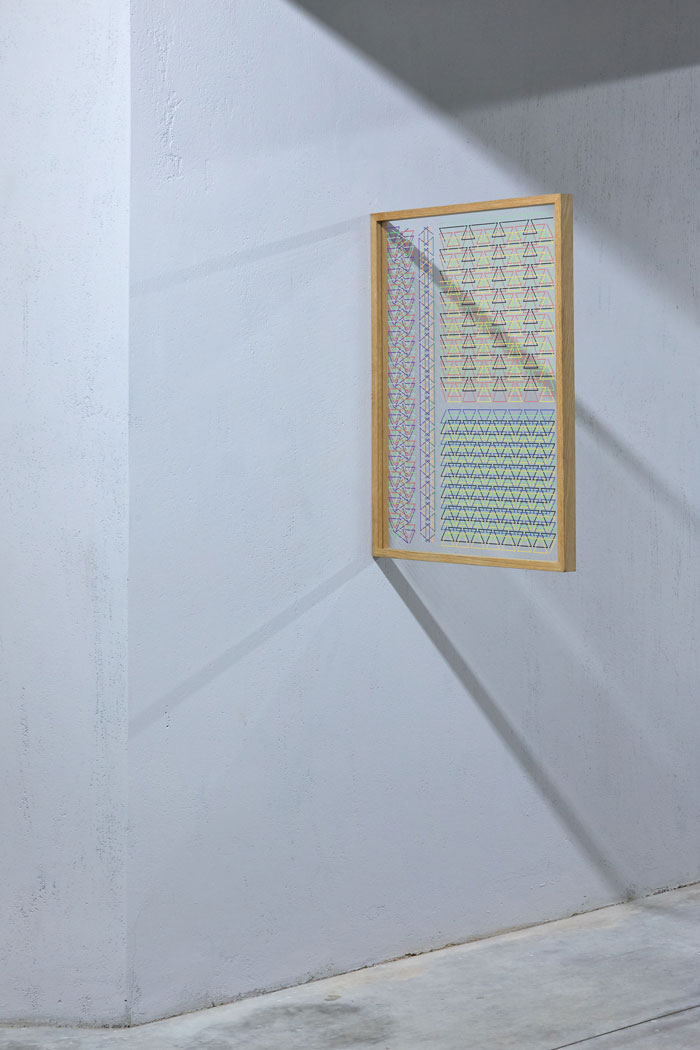

Tauba Auerbach (1981 Berkeley, California, USA) works across various media including painting, sculpture, installation and artists books. Her vibrant but subtle use of colour, and repetition has a meditative quality. Colour theory, geometry and a nuanced engagement with formalism, post minimalism and systems are touch stones. Her work critiques the expectations of a form, and the conventions of a medium – for instance how is a book to be read? Can a book be both sculpture, painting, and have an ongoing durational quality within the invitation offered by its beholding? GHOST/GHOST, with its requirement to be installed on the wall, responds directly to her previous STAB/GHOST which is presented on a plinth. GHOST/ GHOST was made in July 2013 as an edition of 24 copies. It moves literally into the perpendicular, nine colours are silkscreened recto/verso upon 5 mm plexiglass, encasing a complex combination of graphic elements within a specially crafted oak frame. The work is produced by Three Star Books, an independent publishing house based in Paris producing books and editions with contemporary artists.

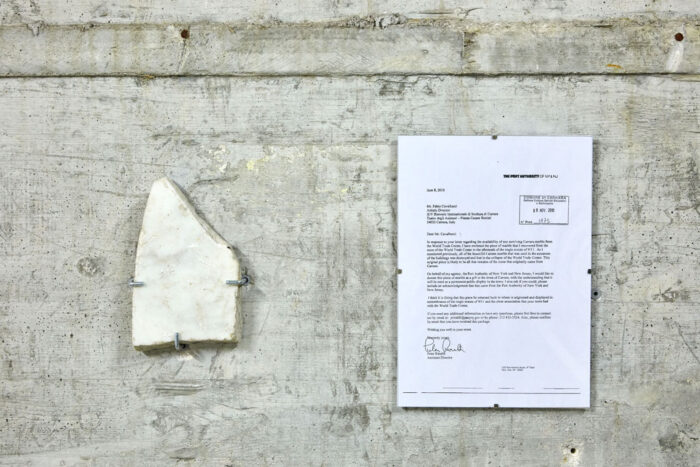

Cyprien Gaillard (1980 Paris, France) made this work for the XIV International Sculpture Biennale of Carrara in 2010. The fragment of marble, originally quarried from Carrara, returned in 2010 to its hometown from the World Trade Center in New York after the tragic events of 9/11. The small fragment is the only “surviving” piece of Carrara marble that covered the World Trade Center lobby. Following the biennale, the work entered the collection of MUDAC and has never been shown outside of the museum since 2010. Since Roman times the Carrara area has been connected with the quarrying and working of marble; it is where Michelangelo found the material to carve ‘the dying slaves.’ The artist Canova, whose sculptures are sometimes carved in Carrara marble, was given Villa Lontana as a transaction by the Vatican for three of his sculptures. The quarries have suffered from the decline of traditional sculpture. The white marble fragment represents a geographical, cultural and historical journey in time, mapping the ongoing desire for authentic Carrara marble. The World Trade Center was designed and built using state of the art engineering, it was, for a short period, the tallest building in the world. The work includes a letter written by Peter Rinaldi (Port Authority of New York) to Fabio Cavallucci, curator of the XIV International Sculpture Biennale of Carrara, on February 28 2010.

Susan Hiller’s (1940, Tallahassee, Florida, USA – 2019, London, UK) research for The Last Silent Movie (2007) took place in obscure, forgotten, or overlooked archives containing sound recordings of extinct and endangered languages to create a composition of voices that are not silent. Sequences from these different recordings of languages, spoken by people of various ages – some sing, and we also hear what might be a mother guiding a child to speak in that tongue. Each of them speaks to us directly to hold our individual attention, as in a private conversation when the implicit meaning is not understood directly though the words in themselves but via their sounds and the ways in which they are uttered. We become those ‘left behind’ – witnessing the passing into oblivion of a language, dead because its native speakers have been subsumed by ‘international’ languages. They are not specially recorded for the film, so the last speaker of a particular language is heard without any kind of re-recording. The work is partly about how these languages are ‘doubly’ lost, because not only are there no more native speakers, but also the recordings of them are in archives almost never to see the light of day. The concept of language as a cultural construction that contains and generates worlds is central to her practice. The sounds of the speakers in The Last Silent Movie invoke language itself as a cultural construction that contains and generates worlds. Instead of understanding the sounds, on an otherwise blank screen, our eyes read the meaning of the phrases, translated into subtitles of a still-dominant language, one that has been instrumental in silencing the speakers.

Thomas Hutton (1983, London, UK) responds to the exhibition with a modular work in travertine and a prototype made in sheetrock and lime plaster which is constructed as a set of architectural structure/furniture. The travertine comes from the Pacifici travertine quarry in Tivoli – with whom the artist has an ongoing relationship. Coloured marble was very precious in Roman times and columns were usually made of local stone and then covered in stucco. The Roman travertine and the prototype exist sculpturally in the space and interacts with the case of marbles. Like a set of cubes, it can be configured and reconfigured in numerous ways. Its classic presence invokes latent memories that the viewer may have experienced in buildings in particular places. Polyglyph is a continuous sculpture, an unending series based on a set of proportions that determine the blocks and slabs. Each set comprises eight blocks and four slabs. Each block and each slab are equal in mass and equivalent to a single sheet of sheetrock. Polyglyph can be realised in any material and arranged in an infinite number of possible configurations. Each time a new set is produced, whether by hand or machine, it comprises an edition of the ongoing sculpture. Each iteration of the set, enables the sculpture to accumulate a fuller picture of itself, a dimension that exists beyond its physical presence. Each time Polyglyph is shown in a new environment, in a different configuration, or realised in a new material it comprises a different facet of the same sculpture. Roman travertine is a limestone. Limestones are primarily comprised of calcium carbonate. ‘Burned’ or ‘slaked’ lime plaster is produced by heating limestone (calcium carbonate) to produce calcium oxide and slaked with water to produce calcium hydroxide. Calcium hydroxide cures into calcium carbonate.

It is likely to be the first time John Latham’s (1921, Livingstone, Zambia – 2006, London, UK) experimental photographic darkroom investigations from 1966 have been exhibited. The darkroom processes that he uses as tools for production are characterised by the way in which they reveal processes through chemical and temporal interactions. John Latham’s diverse artistic output questioned the cultural representation of knowledge in order to question unthinking acceptance of received opinions. These include books; the objects containing histories, dictionaries, linguistics, socio-political and economic systems. In the work on show in MEMORY GAME, Latham explores the chemical transformations from the negative to the print, reverse printing and image fragmentation, through photographic images he took of pages from dictionaries and encyclopaedias – like the fish diagram. Rome held great significance for Latham. In 1944 he was a captain in the allied forces liberating Rome during World War II and he had the opportunity to explore the city. Two paintings by El Greco, at Palazzo Venezia were an “instant vision” for him. “When I saw them” he said, “I knew then that I wanted to be an artist”. This story provided the impetus for the Santarelli family’s and the Dino and Ernesta Santarelli Foundation’s involvement with Flat Time House, London.

Charlotte Moth (1978 Carshalton, UK) re-visits existing footage to make a new work that poetically explores processes of unfolding the future from the past. The artist works across a variety of media, sculpture, installation, artists books, film, photography and collage. Knowledge and sensitivity absorbed through a personal experience of the world combined with nuanced and ongoing exchanges with artists of the past – who are like old friends, are key to Moth’s processes. Libraries, specific collections and their archives and situated architectural spaces provide triggers for her procedural unpacking of layers of histories, narratives and associated memories. In 2014, Moth went to Florence where, as part of a larger project, she filmed inside a very old paper marbling shop. A skilled and elderly marbler gave her a demonstration of the processes. The resulting film, The story of a different thought is more of an epic, complex and rich. But the footage of the ink on the surface of the water was hypnotic. For the exhibition MEMORY GAME, Moth re-visited the footage to create a new edit drawn entirely from the space of the marbling workshop. Her thinking of the Belli brothers’ chest of marble samples in the Santarelli Collection, inspired Moth to re-visit the footage which she felt she had not previously used to its full potential.

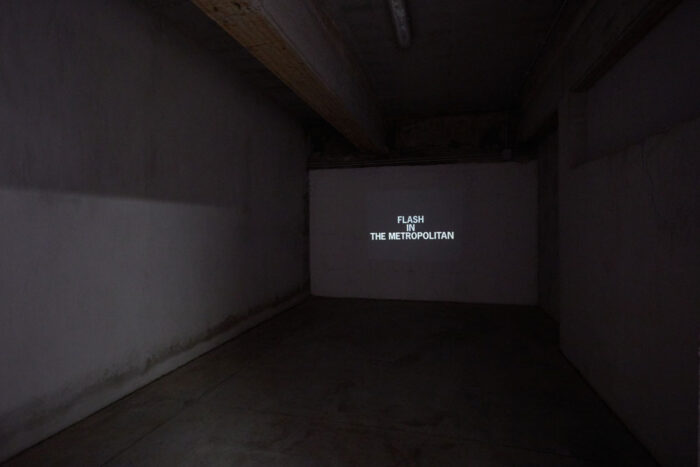

In 2006 the Metropolitan Museum was approached by Spike Island, Bristol, who had commissioned the artists Rosalind Nashashibi (1973, Croydon, UK) and Lucy Skaer (1975, Cambridge, UK), who work independently but also make films collaboratively, to make a new short feature under their auspices. They had an unusual request: they wanted to make a film in the Metropolitan but in the middle of the night. Under the cover of darkness and armed with a flash strobe, a 16mm film camera, and some track on which to move it, the artists glided through the museum, flashing their source of illumination at discreet intervals on freestanding objects and those in cases. As a result, the way in which the works of art are usually presented falls away, and the objects—often ritual or devotional in their original function—become eerily enlivened and animated, almost like characters in a new ritual of unknown intent. Nashashibi and Skaer filmed under the cover of darkness, documenting the Near Eastern, African and Oceanic collections of the legendary Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The flashing strobe light used in the filming allows the viewer to see the objects as if in animation. Disorientation tips the viewer from the logic dictated by the museum framework to one dictated by the artefacts, enabling a new tactile and imagined response which ruptures chronology to create a feeling of non-linear time. They use it as a guide through the space and the works on display.

Olu Ogunnaike’s (1986, London, UK) practice sits between sculpture, drawing, performance and installation. His sculptural installation fabricated for this exhibition responds directly to the architecture of space and incorporates the principles of archaeological deconstruction in the processes to make the work. In 2013, Ogunnaike used wood offcuts to develop a pastiche of the industrial material called ‘Oriented Strand Board’ (OSB) which is made by compressing strands of wood and glue together, to create sculptural work. These installations explore ideas that outline the divisions within our socio-political spaces. For Ogunnaike the species of tree from which OSB is created are motifs of their original territory revealing a displaced experience of space – or ‘locale’. In this way, the composite identity of tree motif performs a complex metaphor for cultural assimilation, domination, migration, and appropriation. As Gnoli explains in Marrmora Romana: “Every kind of marble, like every kind of wood or metal, responds differently to human solicitations, and its character, its value, its beauty depends on the diversity of its response. The machine takes no account of this diversity and under it everything is equal.” Vitruvius’ De Architectura refers to oak, cedar, elm and pine wood showing how their characteristics were, and still are, employed as building materials. Oak is slow to rot and is durable for underground and used in foundations. Cedar also is slow to decay and used more widely as a building material, while elm is noted for its pliable qualities. As to the spreading of these species by the Roman Empire it’s hard to quantify but evidence of oaks discovered in France indicates that oak beams were used as support/foundation beams for early Roman structures. In the garden of Villa Lontana, conceived in the 1600s, are ancient and immensely tall cypresses and pinus pinea, also known as parasol pines or umbrella pines and three cedars from Lebanon whose wood has been used by the artist for the newly made commission for this exhibition.

Giorgio Orbi (1977, Rome, IT) works across media, including multimedia installation with sound, sculpture, painting, collage, photography and film. The actuality of mountaineering and traversing its terrain is a fundamental core of Orbi’s practice. The processes of mapping the altitudes and depths of geographical topographies combine with systematically constructed sound works that play with the club culture scene. It is as if the granite mountain rocks have released their sounds to us. The map, it’s functionality and iconography combine with ideas of the journey, and of migration from one place to another. Parrots migrate to colonise territory, they are now all over the cities of Europe. RomaRomaLondonLondon AmsterdamAmsterdam is a field recording piece of the parrots presence in these cities. Monte Pelmo was climbed in 1857 by the first president of the London Alpine Club, John Ball, witnessed the birth of alpinism in the Dolomites. The history of mountaineering, and especially the architectural intervention of the Alpine Club, in particular into bivouacs and alpine huts, has influenced the way we perceive mountain landscapes. The formation of a knowledge and exploration of the Alps is a fundamental interest for the artist. For MEMORY GAME Orbi created a new sound work, MOUNTAINS. This techno piece fuses layers of hypnotic rhythmic sounds and field recordings of his climbing through ice. A material the artist often returns to is “cocciopesto” which is a building material made of tiles broken up into very small pieces, mixed with mortar, and then beaten down with a rammer. In Roman times coloured marble was very precious; it was only used by the wealthy and only in the most important rooms in their villas. Most floors, including the ones in Pompei, were made using mosaic (which at the time was more economical) and “cocciopesto”, sometimes enriched with colour marble tiles embedded into the design.

Andrés Saenz de Sicilia (1985, London, UK) and Emiddio Vasquez (1986, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic) were invited to respond through sound to a selected number of artefacts in the Santarelli Collection, to unlock their acoustic memories and guide them into a new fusion of inscriptions and conversations. These histories are accumulations of multiple interconnected events and processes, legible at varying scales: geological, civilisational, sociological, psychic, emotional, etc. The objects act as a ‘site’ of condensation, to transpose contained historical energy into sound, as a way of releasing those memory constellations and making them accessible in a phenomenal way, through listening. Sediment Versions (I-IX) is made using field recordings and photographs of the marbles to construct filters that “shave off” frequencies from the raw material of the objects, imagining these surfaces as histories, or writings through which sounds travel. The original sounds are then processed to become the final compositions, like geological sediments that are not accessible when listening to them in their raw state. The artists’ methodology, is an investigation of sounds, digging down like archeologists to isolate layers. Some layers of sound correspond more to a specific object from the set they’ve been asked to respond to, and others relate more to the objects as an ensemble.

MEMORY GAME is the first exhibition presenting the work of Roman based artist Edoardo Servadio (1986, Genova, IT). He situates his practice within the urban Roman development and its history, particularly the subdivision of the territory into 22 “rioni”(districts) and 35 “quartieri” (neighbourhoods). To each he assigns a representative coat of arms, as indicated in the Resolution of the Municipal Council of Rome no. 20 of 20 August 1921. He revisits Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s seminal etchings connected to the iconography and symbolism of the city of Rome. According to the artist, Rome now has no representative territorial symbol except the logo of “Roma Capitale”. In Rome streets names are written on travertine plates positioned at junctions. Roman numerals engraved into them represent the district. The artist aims to restore ancient memories of these locations through a combination of historical, artistic and toponymic approaches. The first stage of his practice was the development and creation of a new typeface, which he names Carattere Lapidario Moderno (Modern Lapidary Font). This font is on all his work. Following the font’s development, he designed a visual identity for each location, initially with their manhole covers. The manholes are cast in bronze and are the result of a long research that began when as a child in Tokyo he was fascinated by the coloured acrylic manholes. The “shop” at Villa Lontana is a prototype for merchandise devised around the Tor di Quinto neighbourhood, where Villa Lontana is situated and it can be applied to all Roman districts. The items in the shop are unlimited artist multiples and may be purchased by order. Servadio devised a memory card game as a limited edition for this exhibition. These display the iconic heraldic-like symbols of his proposed visual identities of the city’s neighbourhoods.

Joëlle Tuerlinckx (1958, Brussels, Belgium) uses a variety of media, from collage to drawing, film and installation. Her approach seems to grapple with how an experience of ‘being in the world’ is somehow present in an elliptical and mysterious way when encountering her work. The archive containing ephemera as much as notations, records, forms of documentation and detritus, are primary sources for her artistic practice. These blend seamlessly into her attenuated awareness of the world and its daily, almost incidental, events. She observes these with a careful, thoughtful eye, enabling the viewer endless possibilities to engage with her work and reflect upon their own parallel experiences. Her use of titles, like The Constellation of Maybe, 2013 and WOR(LD)K IN PROGRESS, 2012, are indicative of her lightness of touch intrinsic to her methodology. These titles guide the viewer into an awareness with a discursivity that is visual, sensual and phenomenological. The work on show at MEMORY GAME is BARRES des RONDS, first exhibited in 2012 in her touring exhibition WOR(LD)K IN PROGRESS, shifts in focus from venue to venue. Each occasion it is installed, the configurations change in order to create a direct response to the space in which it is being shown. It is as if Tuerlinckx treats the work as part of the same unending process of continually questioning the parameters of when a work begins and ends. This indirectly proposes for us the question of whether, and how, a work can end.

Special thanks to Paola Santarelli for letting this exhibition happen and for letting us share her personal connection with these objects.