La mosca

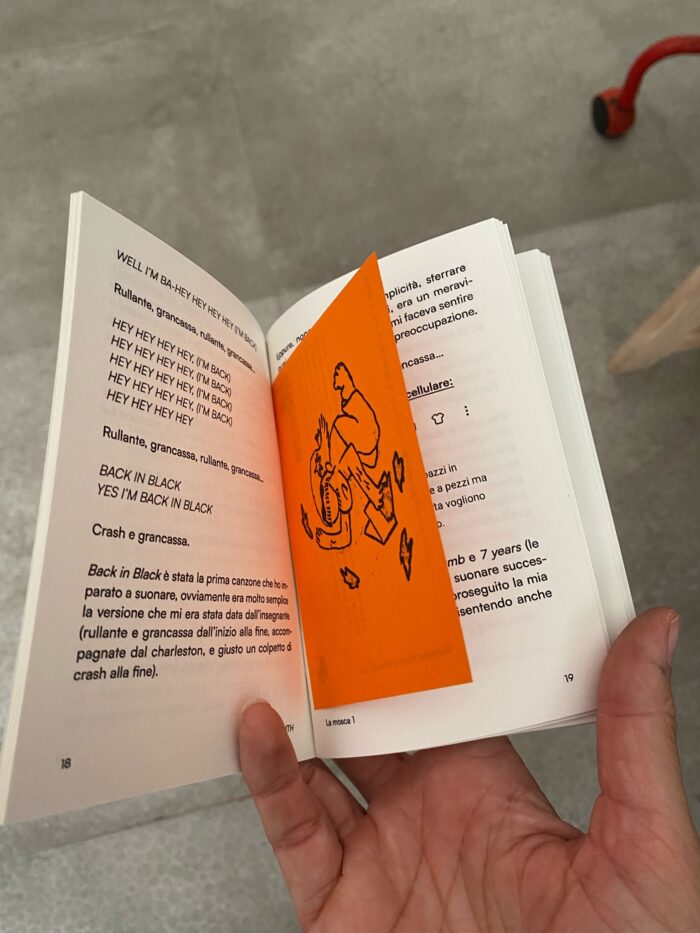

“La mosca” is Ruth’s first printed project, published by Beauroma Books

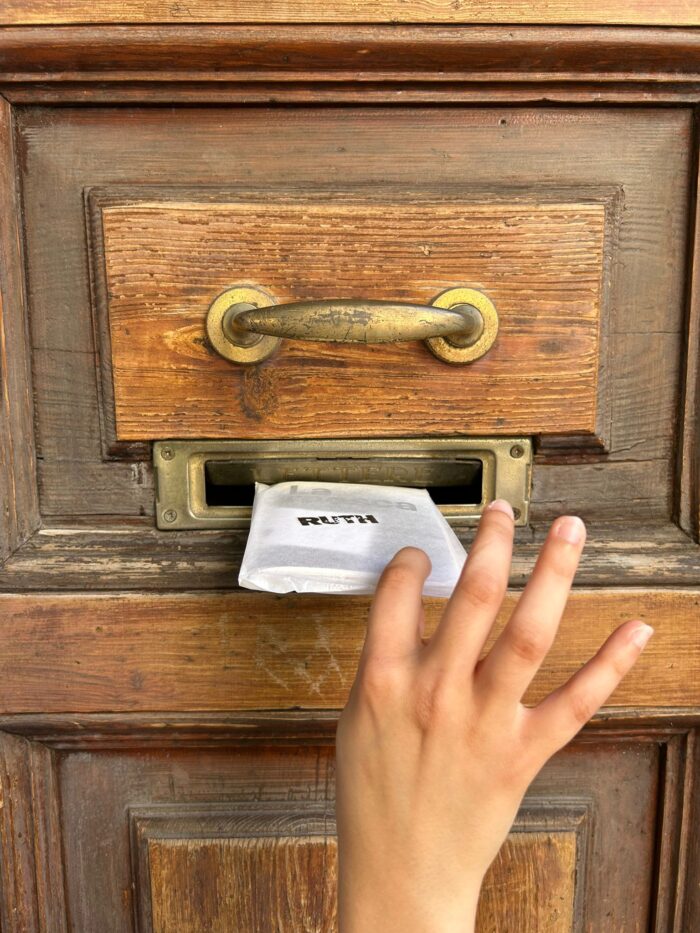

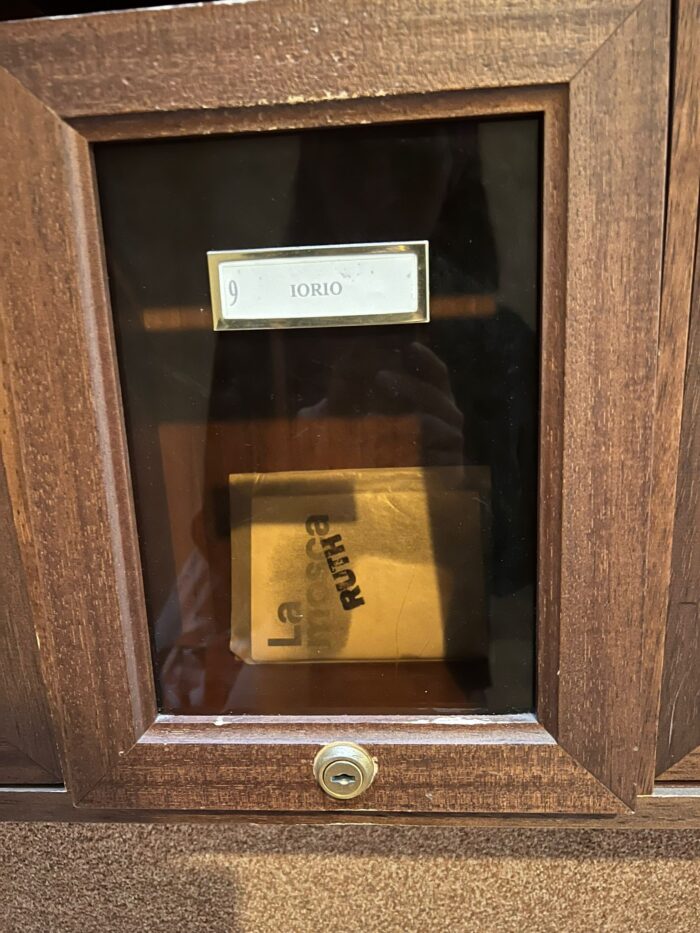

La mosca is Ruth’s first printed project, published by Beauroma Books. It is a small editorial series in which each issue consists of texts selected on the basis of thematic similarities or similar approaches to writing, mainly extracted from the online platform. La mosca was delivered directly to mailboxes, following a random principle that does not involve mailing lists and aims to reach a diverse and heterogeneous audience. La mosca was intended as a gift, and recipients can open it, read its contents, leaf through a few pages, throw it away, or use it for other purposes.

La mosca is a series of small books edited by a group of people who believe in writing, reading, and publishing. La mosca rang the doorbell of potential readers and entered the homes of those willing to take the risk of being surprised.

The first issue of this editorial series contains six texts, some previously unpublished, by Daniele Di Battista, Valerio Gelsomini, Alice Giuntini, Eleonora Sacco, Marco Scirè, Francesca Senatore and Simone Trapani, produced following a psychogeographical dérive. The publication was distributed in the Alberone neighbourhood, replicating the intuitive methodology of the dérive itself.

“The doorbell rings.

It’s not the postman, it’s not advertising, it’s not a registered letter.

You can read it if you like.

The fly is a gift.”

This is a story based on hearsay, a second hand experience in another language, translated therefore—if it weren’t for the fact that the first hand of the experience is made of many hands, almost twenty, which in several phases gave substance to an intuition. This account has happened and was heard in Italian, and it is written in English, thus its language is adjusting while trying to sit on the very uncomfortable seat of translation. This story happened on June 28th, 2025 in Rome, with a temperature of 36.2°C and 42% humidity, almost no wind, in the Appio-Latino neighborhood. Meanwhile Israel was still committing crimes unpunished, an earthquake struck offshore east of Sarangani in the Philippine, and in Serbia, an estimated 140,000 people protested against the government, calling for snap elections and the removal of President Aleksandar Vučić, while the Budapest Pride march took place despite a government ban.

They told me they would meet up early on Saturday morning, to avoid the heat peak, but I could not make it. What I knew beforehand was also based on a rumor, they told me about a walk that triggered the writing, the writing then called for this booklet, and it made perfect sense to distribute it while walking. Psychogeography at its best—but then before we dig deeper into the gossip, let us pause for a moment on the title (again translation here comes in solidly like a glass door between meaning): La mosca, a fly—because this little booklet, collection of writings shall come into your home without you almost noticing, casually. They told me they would have rang the bell and asked respondents if they would like to receive a publication. Now, who rings the bell on a random summer Saturday morning? Usually nobody, it is too warm and most people are away or locked inside, or went to do groceries before it gets too hot—otherwise if you don’t expect anyone is either Jehovah’s Witnesses or Lotta Comunista—anyway, that’s all very nineties, people became suspicious nowadays, no one uses the bell any longer, or send printed matter via mail. Their fly should have landed on both objects in dispute, on the discreet routine of the petty bourgeoisie, on the shoulder first, then on the porter’s nose.

On a Saturday morning “you are probably at the market, or you are about to go, or you are coming back from the market, or you pretend you are at the market… you do not open the door.” More than one person said that, after that, to deliver the book they needed to think of tactics. I heard that apparently they woke up early, met up at the bar, and then approached the first building where the porter’s hand had chased away the fly—“A traumatic beginning and then slowly things went better,” they said they had to find an “escamotage” to let the fly in, to gain the trust of tenants, for them to leave the door ajar to this unexpected read that is delivered by hand, face to face—everything is declared. So, apparently, for the fly to be delivered they had to introduce themselves as students, to submit a profile for scrutiny at the meeting of the Saturday morning sceptics, or try to gain the porter’s complicity. Some encounters said they do not read at all—“They had the audacity…” Some “former math teachers” decidedly said no, as if they felt almost insulted. Everyone went in a fear-of-refusal modality—“a cog,” they called it. They called themselves students “to stir some tenderness.”

Also, they told me they found out that there is seemingly “no grammar to receive a gift,” people didn’t know how to react, and always suspected they will be asked some money at a certain point (it must be said that both Jehovah’s Witnesses and Lotta Comunista do ask for money), and confused “gratuitousness as guilt”—as if it was their “duty” to return the favor. So what is this outdated “door-to-door economy”? Is the fly an intruder or an inspiration? Did the writing happen before or after becoming a booklet? “It was a surprise to see how something you believe in can be achieved thanks to others,” how an impulsive idea got eventually to be distributed around the very same place where it was collectively and materially produced. Beside the event of the delivery, “its realization is what moves me the most,” and they specifically used the term “commotion.” To say what this fly is they made a list, which I noted down in a non-consequential manner. Among other definitions, for them the fly is “spontaneity, a box of shapeshifting fragments,” and so on and so forth.

I heard that apparently La mosca was delivered to the strangest surnames, their favorite was Lascialandare, they said they don’t know if they were actual or fictional surnames. It seems that porters are getting very bored, and although people are nice there must always be someone they hate—“I am happy to be that kind a porter likes.” If this fly is really a “multipliable intuition” that “moves with others,” in its distribution became a “walking deviation” in the receiver’s day. Maybe, if there’s another round of delivery, they “will discover more funny surnames,” because this time, for these hands, the fly lead them into “a concrete dream“ they didn’t want to wake up from, one of those dreams in which “you want to see where you will end up.” I guess they wanted—because I also would like—to sneak in that moment of reading, which is always the case with writing—how does writing become reading after it is shared with some reader, or listener, and the agency is passed onto some other hands: this dream is in the situationism of walking to write first and then walk again to distribute, to embrace the chance of meeting the eyes and the hands of a plausible reader, to do it in person on a random summer Saturday morning, to deliver a collective endeavour that once was just an intuition.

The fly has eventually found my way, by hearsay. I had been following her flight since it still was an intuition, until it became a dream, and then back to the writings that stemmed from their first walk. We all know that writing comes from reading—and the fly has landed on somebody’s hands just to take off onto the next, the fly has brought in some mundane digestions of some eyes that have settled on material details. Is the fly the author or the book itself? Nonetheless the fly slipped in, flying through a window that had been left ajar.