Keeping Animals

Peter Bartoš and the Zoo as a Medium

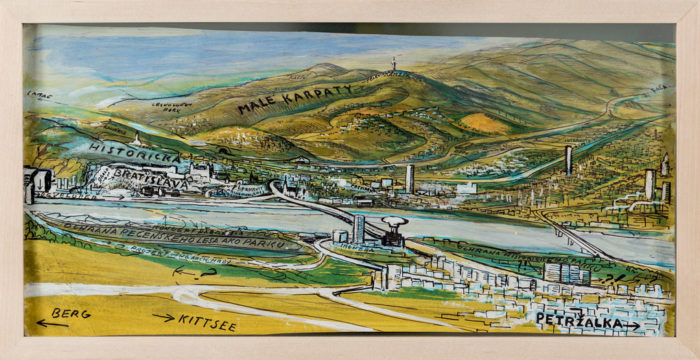

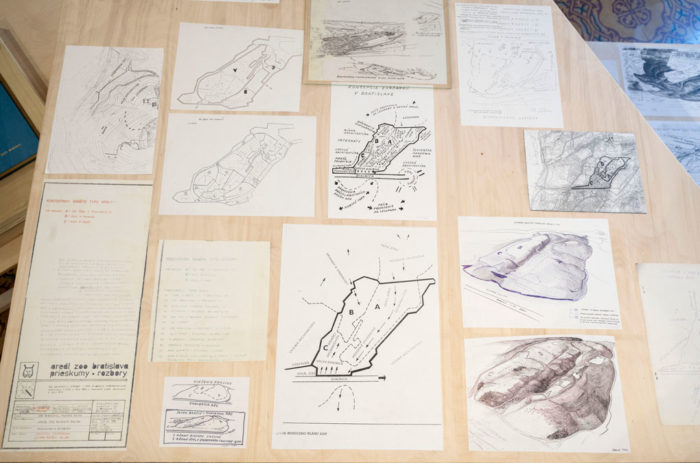

Curated by Mira Keratová, with Architecture Display by Petra Feriancová, the exhibition Environmental Aesthetics displays works by Slovak neo avant-garde artist Peter Bartoš (1938), a radical figure of the Slovak art scene, whose work has still been only partially documented. Trained as a painter, Bartoš wanted to extend the possibilities of painting and make work that would be absorbed by nature. After 1979, he was employed by the Bratislava Zoological Garden (established in 1960) as a conceptual artist. He worked there until 1991. At the same time he also worked for the state construction company Stavoprojekt as a landscape designer for the zoo. The purpose of his employment was, with the consultancy of zoologists, to design the environments for animals and preparation of landscape projects for zoopark. He approached the concept of new area holistically. The following text has been originally published in On Directing Air #2 a project by Petra Feriancová, and an initiative of Archiving Air (© 2018 Archive Air Press Bratislava 2019).

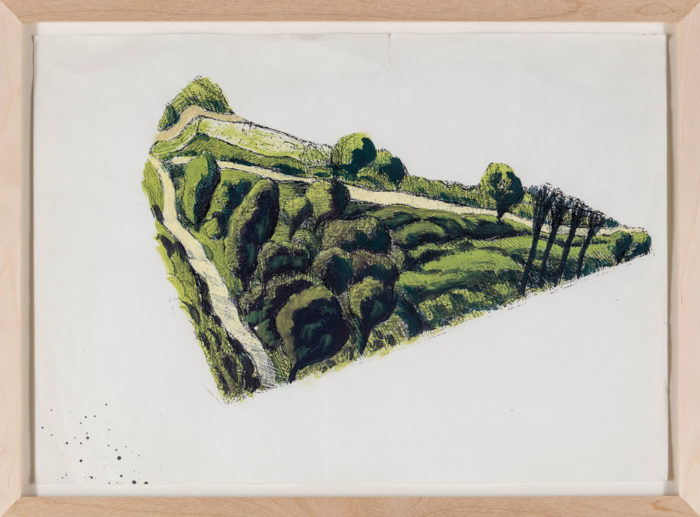

We are walking up the hill, it is a blissful balmy day, with a light breeze. The sky opens, and our sense of space changes slowly. Breath in… breath out… We are leaving the city behind, and now the horizon is marked only by the Carpathian Mountains. On the left, a line of fruit tree saplings helps spare us the view of the newly built student housing, on the right, a meadow with tall grass and a couple of endemic trees. I feel one with the landscape, even though there are tasteful thresholds separating us from the enclosure beyond in the form of a ditch for rainwater and some discreet fencing. We spot the hucul ponies. They are a familiar looking indigenous breed, medium built with a broad chest, short neck, and compact body in various shades of brown. Perhaps aware of being one of the least exotic looking creatures around, they are not too bothered by people and graze gracefully on the dandelions. I notice that the shape of their backs repeats the exact shape of the mountains behind. Petra tells me that this is exactly the kind of poetic comment that Peter Bartoš would make.

Peter Bartoš, Bratislava Zoo series, 1979-1991 Courtesy Fondazione Morra Greco, Napoli

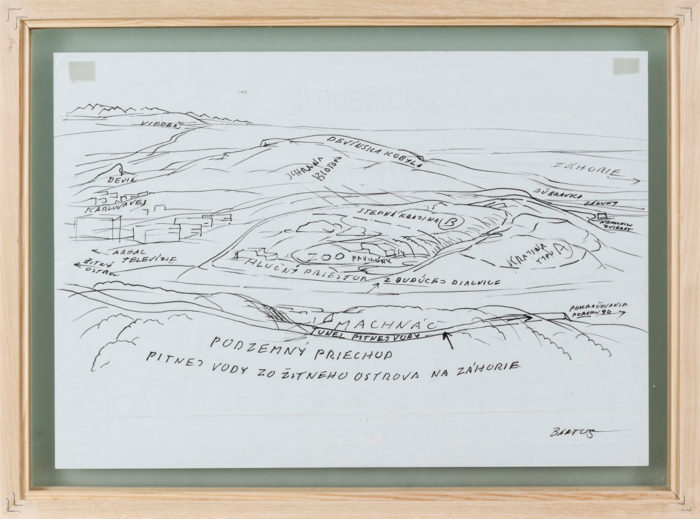

Only parts of Bartoš’ original design for the Bratislava Zoo survives today, but specifically, the hillside for the ponies is still relatively intact. In his concepts, he always thought of the habitats holistically and considered the combined effects of multiple elements. These certainly included knowing where the sun rose and set; wind directions (so that the predators are not constantly tantalized by the smells of prey and vice versa); noise and smog (animals who are more sensitive to this should be placed further from the highway that disruptively runs on the East side of the park); and different paths and experiences for people with various needs (for people who want to be left alone; for lovers; ponies as therapy for kids etc). He stood by the idea that enclosures should be complex systems, rather than just a collection of animals that do not eat each other, and include various flora and fauna that would ordinarily live together in nature.

Bartoš was employed by the Bratislava Zoological Gardens as a conceptual artist where he designed and prepared enclosures and environments in consultation with zoologists from 1979 until the change of the regime in 1990. The habitat of the ponies was envisioned almost like a safari, it took visitors on a long walk and connected them to the context and immediate local environment of the Carpathians, and more widely to that of Central and Eastern Europe, with indigenous species as a preservation of the original biotope. An idea that still delivers, even though at the top of the hill we now meet rhinos. Only a few of Bartoš’ concepts were fully actualized, and while we can still find some reminders of the old zoo—like some parts around the lake, a couple of animal runs and the hippos’ enclosure—certainly they are changing, and little by little being chipped away.

Peter Bartoš, Bratislava Zoo series, 1979-1991 Courtesy Fondazione Morra Greco, Napoli

Peter Bartoš, Bratislava Zoo series, 1979-1991 Courtesy Fondazione Morra Greco, Napoli

When we circle back, on the way down I notice that one of the ponies has an extra coat on to keep warm, in fact as a small joke it is wearing a stripy zebra outfit. The Slovak zebra! At this moment I can’t help but think the expression “you start with a horse and end up with a camel” (or zebra in this case)—a saying that a friend of mine uses to describe situations where the outcome barely resembles the original plan due to too many changes and compromises. The Bratislava Zoo is a result of mixing many contrasting ideas. While on the one hand, it is proud of the breeding programme for the preservation of species that are near extinction in the wild, on the other hand, it majorly succumbs to the entertainment business. It feels like every 5 meters there is a shop or a machine that will take the visitors money in exchange for sweets or small souvenirs; there are trains to ride; playgrounds including a large bouncy mat for kids; and of course as the giant dinosaur at the front of the entrance advertises, there is a dino park at the back as well… It is fascinating to notice these, and many more layers present all at once. The zoo is a contested ground for how we think about our relationship with other species, how to value and represent them through giving space and of what quality, and of course how we see ourselves in the mix.

For most people, the zoo is a place full of childhood memories. For others, it is a strange outdated model of the world that speaks of centuries of abuse of power, exoticization and colonial histories. Perhaps a form that should be scrapped altogether. It is certainly not a guilt-free place for Bartoš either, however, he remains fascinated with it as an environment where he continues to test out his ideas on how we relate to nature. Even today, he keeps working with the site as a concept, rethinking solutions and tweaking parts of it.

Peter Bartoš, Bratislava Zoo series, 1979-1991 Courtesy Fondazione Morra Greco, Napoli

Peter Bartoš, Environmental Aesthetics, 2019, Installation view at Fondazione Morra Greco, Napoli. Courtesy Fondazione Morra Greco, Napoli, © Maurizio Esposito

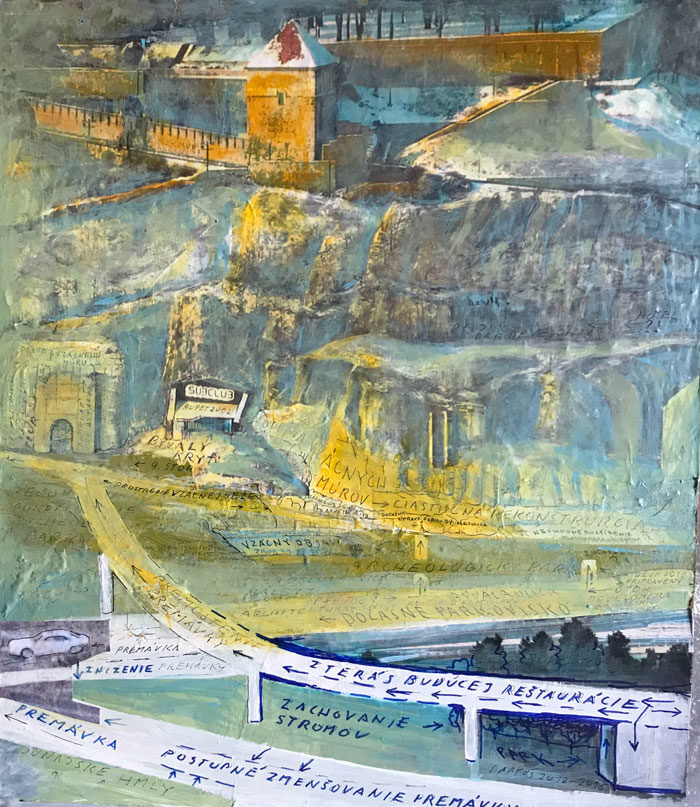

He likes working with the bird’s eye’s view and uses old maps as a base for his drawings. As part of his process he often photocopies previous versions of his work, paints on them or collages several together, hence combining various textures and colors. He says he longs for new photographs, ideally taken from the nearby high-rise building soon to be knocked down. He knows nothing of Google Earth, and his perspective is largely bound to what he can experience by walking through the landscape. Although now in his eighties, he still often goes on long strolls and even tracks through forests in and around the city. I envy his point of view, as I am aware that my (and many others’) experience of nature is overwhelmingly a mediated one through narrated nature documentaries available on Netflix, Instagram feeds of other people’s smartphone photos, and images taken by satellites rendered 3D by algorithms.

How do Bartoš’ actual and conceptual projects sit within a wider and contemporary discussion? He says that he is driven by understanding the relationship between the living forms on earth as well as the formation and creation of an ecological culture. These, together with the Anthropocene, are indeed most important topics for many fields today, including science, ecology, philosophy and art. In recent years there has been a renewed interest in animal studies in the contemporary art world. Think about the exhibition Making Nature: How We See Animals at the Wellcome Collection in London in 2016/2017; the reader Animals, edited by Filipa Ramos for the Documents of Contemporary Art series published by Whitechapel Gallery (2016); or the Serpentine’s long durational General Ecology project developed by Lucia Pietroiusti in collaboration with others. Actually, Serpentine Gallery’s first The Shape of a Circle in the Mind of a Fish symposium in May 2018 took place in the London Zoo, the same location where just a few years before in 2012 Eszter Steierhoffer organised her Zoo-Topia symposium and film screening unfolding a research on the Zoological Gardens in Budapest and London. Turns out, the London Zoo is an especially interesting specimen to observe in terms of the changing ideas for what enclosures should be like. Many of its famous buildings (most notably perhaps Berthold Lubetkin’s modernist design for the Penguin Pool) have been deemed inappropriate as habitats for the very animals they were built for, now ghostly standing as monuments to zoo histories.

Peter Bartoš, Environmental Aesthetics, 2019, Installation view at Fondazione Morra Greco, Napoli. Courtesy Fondazione Morra Greco, Napoli, © Maurizio Esposito

Thinking about ourselves through the eyes of other species is perhaps the main problematics of the zoo, famously unfolded by John Berger in his collection of essays Why Look at Animals? or heartbreakingly in Nicolas Philibert’s documentary Nénette from 2010, a film about a 40-year-old female orangutan living in the ménagerie of the Jardin des Plantes in Paris. Jacques Derrida picks up the meaning of the gaze in his relationship with his cat in The Animal Therefore I am, while influentially Donna Haraway talks about a mutually transformative connection with her dog as a companion species bonded in “significant otherness.” In more recent writings she talks about our entanglement with all the critters of this world on whom our mutual survival depends. Taking seriously animal rights and our responsibilities to them is a pressing issue, especially in the view of how humans have completely changed the distribution and biomass of most species by taking their space away, breeding them to our own benefit and creating a mass extinction.

Peter Bartoš, Environmental Aesthetics, 2019, Installation view at Fondazione Morra Greco, Napoli. Courtesy Fondazione Morra Greco, Napoli, © Maurizio Esposito

Peter Bartoš, Environmental Aesthetics, 2019, Installation view at Fondazione Morra Greco, Napoli. Courtesy Fondazione Morra Greco, Napoli, © Maurizio Esposito

Peter Bartoš, Bratislava Zoo series, 1979-1991 Courtesy Fondazione Morra Greco, Napoli

I am fascinated by Bartoš’ practice in this context, how he relates to the cultivation the countryside, understanding and manipulating living matter, observing or actively preserving it. He has strict ethics regarding his engagement with other species and nature. While some of his ideas were quite ahead of his time, others might be controversial and certainly different to those of today’s ecologists. I find it is important to understand Bartoš’ practice as a product of a certain time, and situated in the art scene of Bratislava and Czechoslovakia. He has been interested in breeding and de-breeding species to their “original form,” first and foremost as an act of care. If it was a cat for Derrida and a dog for Haraway, that initially inspired their writings, for Bartoš’ art practice it must be the pigeons that stand out. He kept them since the 1960s for years, even in his own apartment. One of his projects was breeding the “Bratislava Esthetic Pigeon,” for which he won an award in 1976. Placing value in maintaining a certain type of heritage and nationalism in nature can also be read as a longing for independence and rebelling against the internationalism on the communist regime. In his city views and topographic paintings he imagines other possible scenarios and develops ideological, or sometimes almost religious messages, and hence critically comments on the contemporary situation. He criticizes city planning and developers and instead encourages the preservation of certain ecologically important sites. Many of his locations—like his fascination with the zoological gardens located at the edge of the city, the under-Castle area, and his actions in other hills around Bratislava—speak of a need for escapism. While it would be over-simplistic to assume this as a general rule to all his projects, I do think of it when he is looking for connections with the natural environment, studying and designing parks and paths which allow the visitors to get lost, not only to get away from the noise and the buildings, but also because different rules and freedoms apply here.