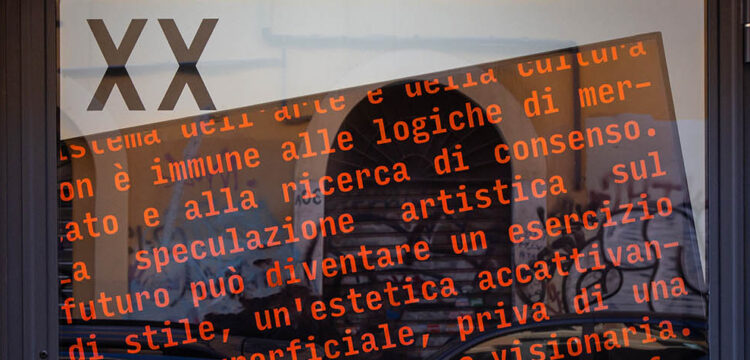

The Beneficial Catastrophe of Art

Achille Bonito Oliva on Jimmie Durham, poetry and art

On the occasion of the reopening of the spaces of Palazzo Caracciolo di Avellino, Fondazione Morra Greco presents the first series of exhibitions with works from the Morra Greco Collection, which includes more than one thousand artworks by circa two hundred contemporary artists. For the first time the collection will be shown in Naples, through curatorial approaches and focusing on the single artists, aside the residency program and commissioned productions, starting with artists Jimmie Durham, Peter Bartoš and Henrik Håkansson. Hereby art critic Achille Bonito Oliva on Jimmie Durham, courtesy Fondazione Morra Greco.

The founding position of the art of Jimmie Durham, a Cherokee artist and therefore a native American, is nomadism, the continuous shift towards one’s own boundary, towards the inevitable fracture of every balance of language. And this happens through the difference of the work, which refuses to homologate to the other works and lives the solitary condition of its own superb discontinuity.

The rapacious time, by Hölderlin, robs things in its vortex and scatters them at the foot of the angel of history, stunned by so much rubble. Only art can stop such collapses, only the angel of art can resist shattering and create a mould, a wedge insinuating between fragments and founding a persistence, a resistance and an armistice. But this does not mean paralysis or concealment, it does not mean balsam or phàrmakon, but rather responding to the dusty and anonymous dissolution of the everyday with an even more striking acceleration.

The movement of art is that of catastrophe, exaltation and intensification of simple time, accompanying daily reality towards its own demise. Because only for art death exists, for the everyday a thousand deaths exist, always different and never exemplary. Exemplarity is constitutive of the language of art and of its nature. It disposes and it is disposed in such a way as to welcome the burden of time inside and above itself, containing it truly by virtue of its own exemplarity and succeeding at the same time in preserving its essence.

Jimmie Durham, Head, 2006. Courtesy Collezione Morra Greco, Napoli

The glimmering moment of exemplarity, the incontrovertible and irreducible moment of the glaring presence of art, is certainly not programmable or predictable. Instead, it is a stumble that helps the artist to fall and better crash to the floor. Language contains within its own skin the thickness of a total time, that of birth, development and death, which does not live apart but compactly inhabits the work in the continuity of a flagrant and instantaneous presence.

To poeticize: “the most innocent of all matters”, Jimmie Durham seems to be affirming with his work “Something… Perhaps a Fugue or an Elegy” (2005).

The work bears witness to the position of art and the artist, led to orient themselves through an innate grace that borders with innocence and skill. Making art means starting from the awareness of one’s own opulence, from the idea that man has been given the gift of language, the preciousness of a tool that plays the inner note. Language is the instrument of lightness and downfall, never set in a single direction, always open to movement and exchange.

Opulence also means excess with respect to the common heritage, it means managing a gift that is able to found the double possibility, that of behaving at the same time as a shelter and a danger, as an increase and an imminent loss. Because the artist works with the stumbling of the feet, and the view turned towards the inside. Language can never be erased, cannot retrace its steps, and therefore it constitutes a danger because in its uniqueness it jeopardizes the great gift, the power to affirm and speak the existent.

Art is the ability to put language into circulation, to hot forge it according to the impulse of exchange. It arises from the natural predisposition of language to adopt a gentle inclination, that of raising the tone of voice, of speaking outside the care of the everyday, perhaps naming the gods, the forces that are placed under and above us, support and heavy task to bear and to respect. The gods probably bring irony to the creation of art, as they feel the divine power of creation threatened.

But art has no envy for the gods, taken with the desire to keep within itself the sensuality of a language that never leaves the earth but blends into it and then rises. What do the gods know of the world, since they always look at it from above? How do they suspect our reality if they are distorted and condemned to eternal happiness? This is why the angel of history, that of Benjamin, has his mouth wide open, like the snake of “Un momento tranquillo” (1991-2007): it is the wonder to open it wide. He discovers the land of ruins that accumulate before his gaze relentlessly.

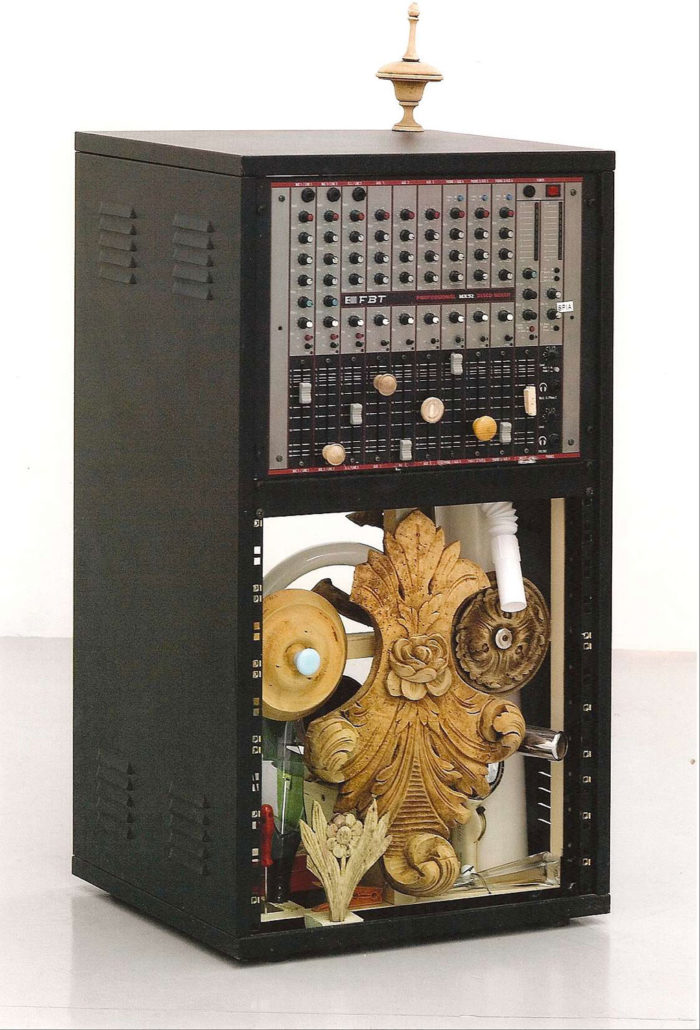

Jimmie Durham, Bajo el Volcan, 1991-2007. Courtesy Collezione Morra Greco, Napoli

The gods are condemned to always fly high, far from punishment and close to inebriation, far from matter and close to the impalpable. Only in the matter, within its dense viscosity it is possible to attest to the total time, to feel the danger of a loss that can annul the obtuse happiness of the gods: its practice is too guaranteed, in an empyrean with no time and no voices. Instead, in the time of the world, art lives its adventure, dodging it at the same time. It is born among a thousand calls and many warnings, at the intersection of the stop and the start-up.

In the interlocking of the two moments, in the jumble of inside and outside, art speaks a language that escapes from solitude, from the vertigo of the gods from which no echo arrives. Instead the tongue of art is always forked, it speaks around itself, establishing contacts and understanding. Because art wants to affect, to be welcomed in the world, to conjugate the verb to the letter: to move simultaneously, together with the incessant motion that regulates things. If the gods tend to an unlistenable and incomprehensible language, instead art is arranged in a circle at earth level to recite its own rhythm. See “Bajo el Volcan” (1991-2007).

Since we have been a conversation it is possible to re-establish the circuit, put beauty into the circuit, arrange it in such a way that its communication takes place smoothly, in the pleasure of its creator and in the admired amazement of its visitors. Art restores flow and understanding, the word and its listening. The happiness of the circle preached by Nietzsche, puts an end to the wholly vertical happiness of the gods, who enjoy the distance taken from the earth. Art provokes the discomfort of a different happiness, all played in its hovering always on the same ruins, the earthly ones.

“The encounter of man and man is a potential tragedy” (Ortega y Gasset). Art operates precisely against this principle, it tries not to soothe but to accelerate the tragic sense through the pleasure of a work that carries within itself the cycles of many adventures and vicissitudes. The tragic potential develops in the communication, in the actuality of a conversation that unfolds starting from the intensity of the work of art, from the place of maximum acceleration and maximum slowdown of the tragic sentiment.

The opulence of art consists precisely in this, in the exuberance of a feeling that does not stop in front of any economy, not even that of loss. I have never heard of a lost or a losing god, but always triumphant and prevaricating. Art runs on all paths without the opportunism of the goal to reach, it climbs on every obstacle taking it off guard with the leap of a very long run. Then it lets itself slide on the slopes of things, sparing no expense, forcing the inertia of a beauty that sometimes tries to remain confined in its privacy: “You Cannot Book a Judge Under Cover” (2006).

Jimmie Durham, You Cannot Book a Judge Under Cover, 2006. Courtesy Collezione Morra Greco, Napoli

The thousand arrows of language depart in all directions, triggering in the heart of distant things, establishing mobile and lasting relationships. Art takes on the iconography of a Saint Sebastian who starts from his own body, from his beloved matter, to extract his own arrows by himself and throw them full hands, with much generosity. The tip establishes the direction of the desire to hook the wonder of the world. Art practices the hand-to-hand, the struggle of the conversation, the word of mouth that should keep everyone on the alert.

To do this it is necessary to commit, to choose shapes and colours that create fascination, that admiration that bends the rigidity of things and makes them turn their heads. The work plunges into the matter to trace the flow and the depth of the ruins, it circulates freely in the past, in the present and also in the future through a push that defeats every law of gravity and temporal progression. The art finally stops its splendid isolation, it goes down in the middle of the matter, it rises above its shoulders, which then actually means that we are a conversation.

But which portrait of the world does art make? What kind of eye does it apply to look at things and look at itself?

There is a dispute between Zeusi and Parrasio, a competition on the perfection and the ability of art to portray things. Zeusi paints a bunch of grapes, so perfectly deceptive as to attract some birds towards the painting to peck them. Parrasio paints a veil with such perfection that Zeusi tries to lift it to see what has been painted below. Both tests tend to hold the representation under the sign of mimesis.

Another myth tells of Zeusi who wants to paint a portrait of Beauty, of Helen of Troy. Without using any model, without starting from reality, Zeusi portrays details of various women, creating an image of composite and mental beauty, corresponding to an abstract ideal. Now art does not want to deceive the world, it does not want to forge things through the fiction of an ape-language. Because it possesses a persistence, the permanence of a temporality that instead escapes everyday things, as in the work “Head” (2006).

Time becomes an explosive lump that also preserves the astonishment, the appearance and the elapse typical of fireworks. “Fireworks are apparitions par excellence: empirical manifestation, free of the burden of empiricism (which is the burden of duration), sign of heaven and product of time itself, premonition, a writing rising and fading away, and yet not a writing that has any meaning we can make sense of” (T.W. Adorno, Aesthetic Theory).

The catastrophe of art does not resemble the simple disaster of passing time, it does not mimic the potential tragedy, but rather operates on the potential to develop a movement that identifies it and separates it into an estranged and alienating image. If ruin produces a negative state of mind, the work of art instead produces wonder. The thaumàzein, the wonder, is the condition of aesthetic contemplation in front of a different reality, intensified by the introduction of an element that is extraneous to things. “In every genuine work of art there is something that is not there” (T.W. Adorno) as demonstrated by Jimmie Durham with “Elephant Skull Study # 2” (2012).

The transience of the image prevents art from pausing to make the faithful portrait of the world. Like fireworks, it tends to penetrate the gaze through the sudden explosion of shapes and colours that are distributed in the work according to an internal dynamic. That does not mean improvisation, but calibrated ability of art to give itself epiphanically as a surprise that leads the gaze to stumble inside the work and to amaze it through an image that foretells the outside world and overcomes it all at once.

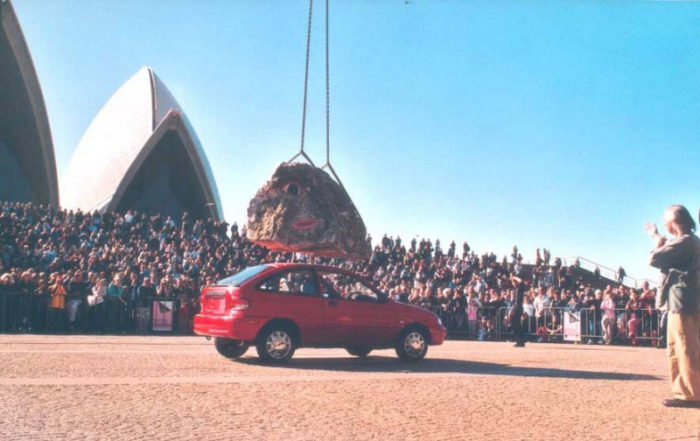

Jimmie Durham, Still life with Stone and Car, 2004, Sydney Biennale

The work of art rejects the descriptive meticulousness of Zeusi and Parrasio and also the conceptualism of Zeusi, to access a different condition of the work, made of a matter that does not fall to the ground but contains all its gravitational weight. The surprise comes from the estranging capacity of art to overcome expectation, to put the surrounding world in check, as superb catastrophe and intense epiphany. Before art all mouths open wide and the irony of the gods is silent.

The wonder comes from the fact that art generates suspicion around itself, due to the references and the peremptoriness with which it closes itself in a circle: a movement in pause seems to be its substance.

The work is a leap to the eyes, at the same time crouching in its own frame. The forked tongue of art is an undetermined intention. The work lights up under the gaze, following the intermittences of a breath that belongs neither to those who are with their eyes wide open nor to those who keep them closed or tightly in their pockets, like dreamers.

Art is not a dream, nor a feverish state of wakefulness for those who are busy around. It is useless to be awake. Art occupies the intermediate space, the interstice between the two moments. The artist is rightly fickle: he pursues the possibility of catching on the fly, with the expertise he can afford only through his usual manual skills, the moment in which movement and stasis converge, where the image goes to settle, the possibility of language to give itself as representation. As happens with “In the interest of science” (2012).

“It is time to talk about poetry again, to let oneself be sucked and fascinated by art, accepting to be moved by it, to move along with its movement. Poetry is the place where the clash happens happily, where the work and the gaze find the point of armistice, of braking clash.”

The epiphany of art, its value, consists in the quality of giving itself as an apparition and revelation, as a sudden blindness that takes the eyes and makes them roll to the inside. Art turns the pupils inside the beholder, it tends to act as a gaze turned towards the interior. In order for this to happen, it is necessary that the work be made artfully, that in its execution it can manifest the multiplied workings of time and its fall as a concentrated immediacy, like a firework that rises, furrows the sky and then dissolves pointing towards the earth.

The artist’s hand contains within itself the space and the strength to make these fires explode, to start a representation in the opera theatre which is interminable, has no end and no aim, if not that to convey and produce a perspective of pleasure, a drift of pure going which finds in its own illumination the possibility to acknowledge the power of art to make permanent what seems to be moving and passing instead.

It is time to talk about poetry again, to let oneself be sucked and fascinated by art, accepting to be moved by it, to move along with its movement. Poetry is the place where the clash happens happily, where the work and the gaze find the point of armistice, of braking clash. Before art, before artfully made artworks, even the gods hasten to descend from the empyrean and to fall directly upon an unimaginable catastrophe, not contemplated by the order and disorder of things.

Amazement is therefore not a feeling that affects only men but touches all those who look at art and recognize that nothing similar exists in nature.