In the Eye of the Eagle

Angelika Burtscher and Daniele Lupo in conversation with the artist Antonio Rovaldi

Artist Antonio Rovaldi’s research revolves around the perception of places and landscapes, always in relation to the various media used, whether photography, video, sculpture or sound. The dimension of the distance between places, their physical and mental crossing, be it real or imaginary, are a constant in the artist’s research. For the project FLUX – Fluvial Actions and Explorations, Lungomare’s multi-year project, the artist traces the River Adige from source to mouth, along with the surrounding fluvial environment.

The project stems from the collaboration of various cultural institutions such as Foto Forum, Lungomare, Museion, NICHE (THE NEW INSTITUTE Centre for Environmental Humanities) and Grenze-Arsenali Fotografici. Thanks to this network, the project features a programme of activities in the various cities along the river, including Bolzano, Verona, and Venice. The project is curated by Angelika Burtscher and Daniele Lupo and produced by Foto Forum and Lungomare.

Angelika Burtscher and Daniele Lupo: Between spring and autumn 2023, you walked along the Adige River, from its source at Passo Resia in South Tyrol to its mouth at Rosalina Mare in Veneto, where the fresh water of the river meets the salt water of the sea. What kind of territories did you encounter on these journeys and what memories stick with you?

Antonio Rovaldi: For me, moving along the course of the river was a way of piecing together fragments of its territories and of my memory in relation to my present time.

I did not only follow the course of the river in one direction, from source to mouth, but I also went back up, as if I had left something behind. A kind of syncopated rhythm, two steps forward and one step back, following the banks of the river but also opening up to sudden changes of course. The waters of the Adige flow along the Venosta Valley in a restricted space, following a rigid line, and before breaking out and finding a more harmonious course, the river has to pass Rovereto, with its Jurassic rock formations and manmade landscape. This was well expressed by the Veronese geographer Eugenio Turri in his book Weekend nel mesozoico… “The reality of man in the landscape: his presence reflected in the eye of the eagle.” [1]

Of the River Adige, its territory and its complexity, no linear image sticks in my mind but rather fragments of memory. In the high territories, it’s a grey river, a channel flowing within its confined banks, also carrying with it the memory of tragic tales, of military barrages, damp corridors where cement seeks to mimic stone, camouflaged beneath the moss of the forest… At its origins, the Adige still speaks to us of war, of submerged lands and uprootings that have never been reconciled, and of a present, that of bell towers photographed by tourists and saturated, shiny surfaces, with apples that are jetted off to the other side of the globe. The Venosta Valley is a compressed territory; there is little space left. The land is all taken up by intensive farming, and the river running through it is a line drawn with a ruler, parallel to other asphalt lines, such as the cycle path and the state highway. It’s a landscape that doesn’t leave much room for imagination and it wasn’t easy to narrate. And yet, despite the fact that the river crosses the territory as an abstract line with an artificial riverbed, it still remains a living body, never static, and it is important to plan its future by making long-term projections: to try to imagine those territories not only in ten, twenty, fifty years, but over a longer time span. It’s a complex reflection, and here I can only hint at my own practice as an artist, crossing a geography and trying to understand how to position myself, where to fit in between the interstices of an extremely anthropogenic territory. There is always a residual space to penetrate in order to set in motion a thought of conscious rebirth, and our role as artists is to try and reread this space in dialogue with communities coupled with a specific and technical knowledge of places. Perhaps we should start again from the forest and its silence, walk at mid-altitude, from a position that is neither too low nor too high, and examine the valley where the river passes, engaging our panoramic gaze in an optical flow. In other words, walking with the gaze, training our eyes to a condition of continuous, associative movement, capable of reading the connections that always exist between geographies and their inhabitants—both human and animal—that populate them.

Your book Morgen – Torno indietro un attimo is being published to coincide with the exhibition at Fotoforum Bolzano, and a selection of the images on show will enter the Museion Bolzano collection. The book opens with the magnificent Movement Solves Everything by French writer Sylvain Tesson, and literary references return with great frequency throughout your work, particularly in your books. What role is played by the word in this interweaving of literature and photography in your work? And to go back to the quotation, what does it mean for you to be on the move?

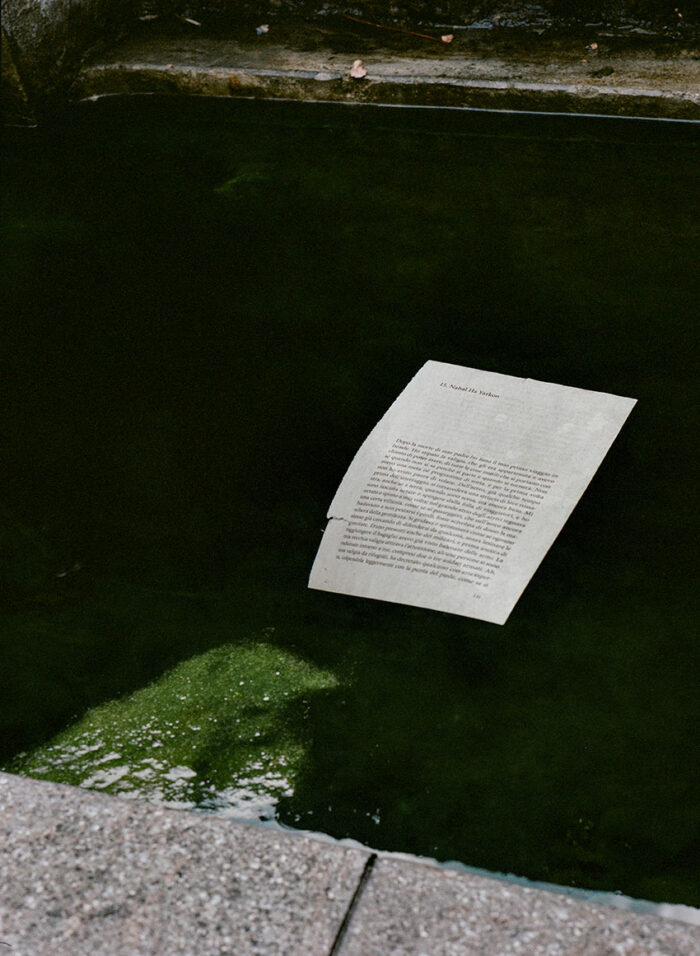

I am delighted that some of the images in Torno indietro un attimo will find a home in the Museion collection in Bolzano, and to have shared every single phase of this project with Lungomare and Foto Forum. Working in a group is wonderful, not just necessary. Trentino South Tyrol has always been familiar territory for me. I used to travel there with my parents and my brother to spend both summer and winter holidays. During those car journeys—which to me seemed endless—we always stopped in Merano. We would stay overnight to break the journey, and in the morning, after a hearty breakfast of Schüttelbrot and local jams, we would drive to Val Pusteria. As soon as we arrived at our destination, my mother would dress my brother and me like two shepherd boys in some alpine pasture: prickly woolen shirts and tough leather trousers decorated with edelweiss. Those unforgettable Lederhosen that occasionally re-emerge, hard as fossils, from the depths of the attic. The River Adige, which you could not see from the car because it was hidden by the Brenner motorway, I must say I have only now discovered while walking along its banks. Last summer, before setting off on my river wanderings, I read two books by the German writer Esther Kinsky and was struck by the photographic lucidity of her writing, which often focuses on wetlands and marginal areas. I felt an intimate sense of familiarity with her gaze. I found out that Esther lives in Italy; I wrote her a letter and went to visit her in Friuli, and then I invited her to share the idea behind this project with me: to try to tell the story of the river in all its complexity. For both of us, the Adige was an image layered in our childhood memories, albeit with different stories and times. When I approach a new project on the move, the questions are almost always the same: where do I come from? Where am I going? At what speed?

Movement helps me to bring these trends into dialogue: writing as a concise and rapid translation of what I see on the move, and photography as a pause, a point along a line of a complex pattern. It is always a question of the distance between things, and I try to reflect places through their punctuation, which then translates into a sequence with a rhythm of its own. As Mark Strand says in his poem Keeping Things Whole: “I move to keep things whole.” [2] Crossing this territory on foot has also been a way for me to keep things whole. Once, writing about my practice in my first book Marcamenti, [3] critic Emanuela De Cecco titled her opening text: Stare dentro, stare fuori (Being Inside, Being Outside). Even today, years later, I find myself thinking back to that title.

The landscape and rivers unfold and evolve through stratification, sedimentation and erosion. In this process, traces of the past are constantly being covered and uncovered. What we can perceive with our eyes is only a small part of what a river tells us. What is time for a river? And what did the Adige reveal to you among its sediments?

We only look at the landscape on the surface and are no longer able to make future projections because we are both intemperate and intemporate: illiterate before any understanding of time. These river journeys along the banks of the Adige revealed a lack of awareness of geological time, starting with my own. “This ignorance of planetary history undermines any claims we may make to modernity. We are navigating recklessly toward our future using conceptions of time as primitive as a world map from the fourteenth century, when dragons lurked around the edges of a flat Earth,” wrote Marcia Bjornerud in her book Timefulness. [4] I reflected on this when I reached Rovereto, and indulged in my first real detour along the river route: the paleontological site at Lavini di Marco, on the south face of Monte Zugna. There, in the early 1990s, the first dinosaur footprints in Italy were found. On an almost vertical Mesozoic rockface, the footprints of their passage may be seen. Walking over it—being careful not to slip down the rockface—I placed my own foot inside one of those large petrified footprints, and as I turned my panoramic gaze over the landscape, I felt almost giddy. In the Jurassic period, those territories were partly submerged by the sea, and the notion that dinosaurs might have been present had never been entertained. Then one day, a pensioner from Rovereto, a keen naturalist, took some photographs of those holes in the rock and handed them over to the MUSE in Trento, which confirmed his suspicions, and from that moment, the chase for giant reptiles all over Italy was afoot. From that point on, the river begins to spread out, widening and preparing to face the plains, before concluding its journey in the Adriatic Sea. When I arrived at Rosalina Mare, hot and tired, I saw a crowd of bathers huddled on a jetty to photograph the sudden appearance of a group of dolphins leaping into the air at the point where the river meets the sea. I remember thinking how ungainly and heavy human bodies are compared to the grace and lightness of nature. I ate a banana and a bar of chocolate, fell into a deep sleep on a marble block, and when I opened my eyes again, both the dolphins and the bathers had disappeared.

“Becoming bodies of water” is a chapter in the FLUX-Zine and tells the story of how the human body connects with water, and how water shapes the life and memories that remain. What stories did you encounter on your journey along the River Adige, and how does the presence of water affect human beings?

As I walked along the River Adige, my attention was mainly drawn to the junctions between the river and its tributaries. Bodies of varying intensity and color meet and begin to study each other before merging, only to continue their journey seawards. When this merging takes place, you can sense the full force of the river, the power of a body that grows as it proceeds, adapting its course to the obstacles it encounters. The river carries with it both natural sediments and anthropic layers, but also, and above all, the stories of those who have inhabited it. This is when it becomes of key importance to go back to walk through places at a slow and immersive pace, giving yourself the chance to look at things again and stop to talk to people. “The secret of seeing is to sail on solar wind. Hone and spread your spirit till you yourself are a sail, whetted, translucent, broadside to the merest puff…” American writer Annie Dillard said it so well in her Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. [5]

Walking by a river gives us the chance to become translucent sails again, responsive and ready for the merest puff of wind. It takes practice, getting used to returning to and listening to landscapes, not only visual but also aural and olfactory. You have to give yourself time. To move. But also stop and look. It’s true… We are bodies of water!

Moving among the sediments of the past, the animal tracks, and the stories of the people you met, what did the river tell you about its future?

The space of the river is a space of primary importance and even though it currently seems to be drastically diminished and compromised, we need to continue to look at it, read it, represent it, not only with the “technical” tools of landscape but also, and above all, through art and its potential for representation and projection.

Returning to inhabit river landscapes, besides being desirable, is an image that must be mentally cultivated even at a distance. The river is the space of movement par excellence, its matter in continuous transformation, and remains a perfect metaphor for our inhabitation of the Earth: we are born, we grow, shaped by what surrounds us, and finally we prepare to reach an outlet. We need to return to a panoramic and not just a frontal gaze. To look at the river from more than one point of view—from in front, from behind, side-on etc.—to rise a little from its course, to observe it from above with the eye of the eagle, as Eugenio Turri suggested in his far-seeing Mesozoic weekends. To do this, we need to get moving, light-footed, at a slow but not-too-slow pace. The future of the river lies within how we look at it and cross it. If we hone our gaze, adopt the right rhythm and take the right breaks, things will start to move.

I always like to tell my students: when we move, things move!

[1] Eugenio Turri, “Lo sguardo dell’aquila” in Weekend nel mesozoico, Cierre edizioni, 1992.

[2] Mark Strand, “Keeping Things Whole“ in Selected Poems, Alfred A. Knopf, 2002.

[3] Emanuela De Cecco, “Stare dento, stare fuori“ text opening the catalogue of Marcamenti by Antonio Rovaldi, Essegi Edizioni, 2005.

[4] Marcia Bjornerud, Timefulness: How Thinking Like a Geologist Can Help Save the World, Princeton University Press, 201.

[5] Annie Dillard, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, Harper & Row, 1974.